What we’re thinking

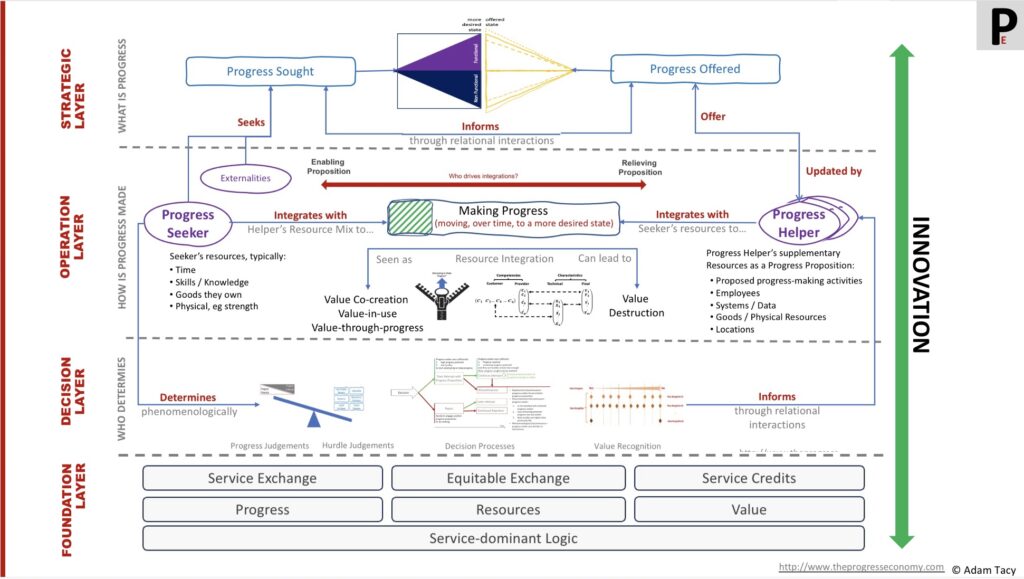

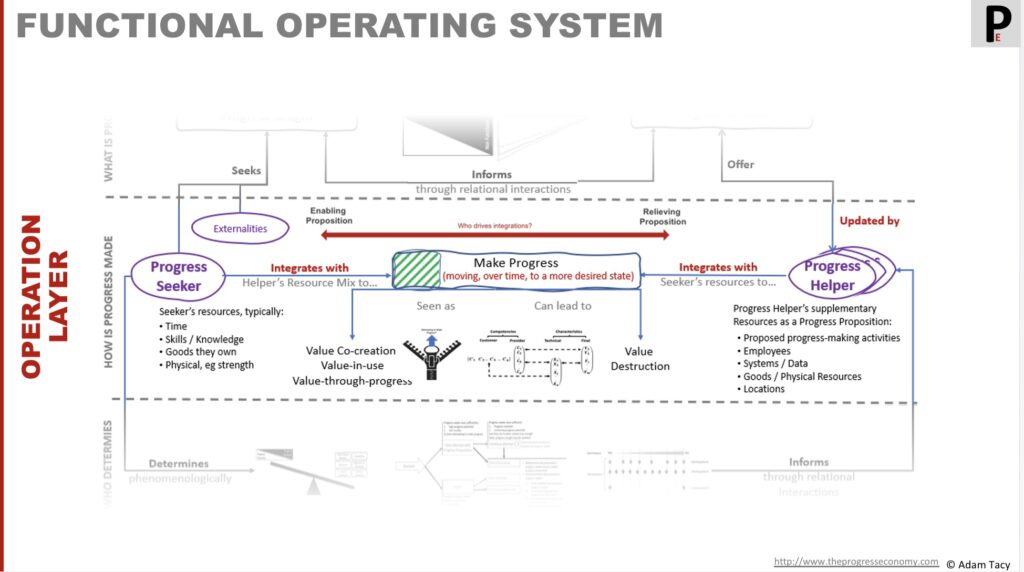

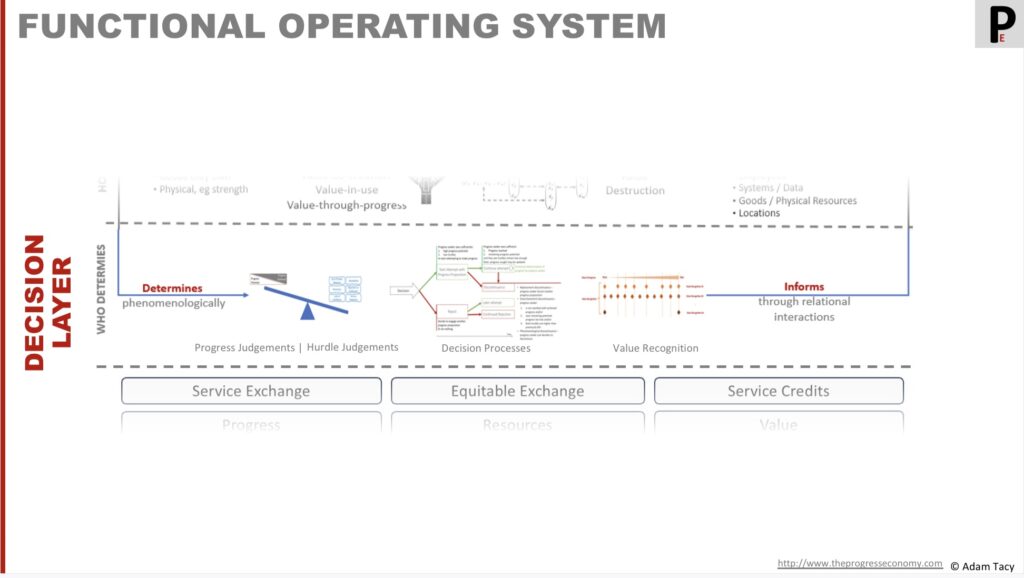

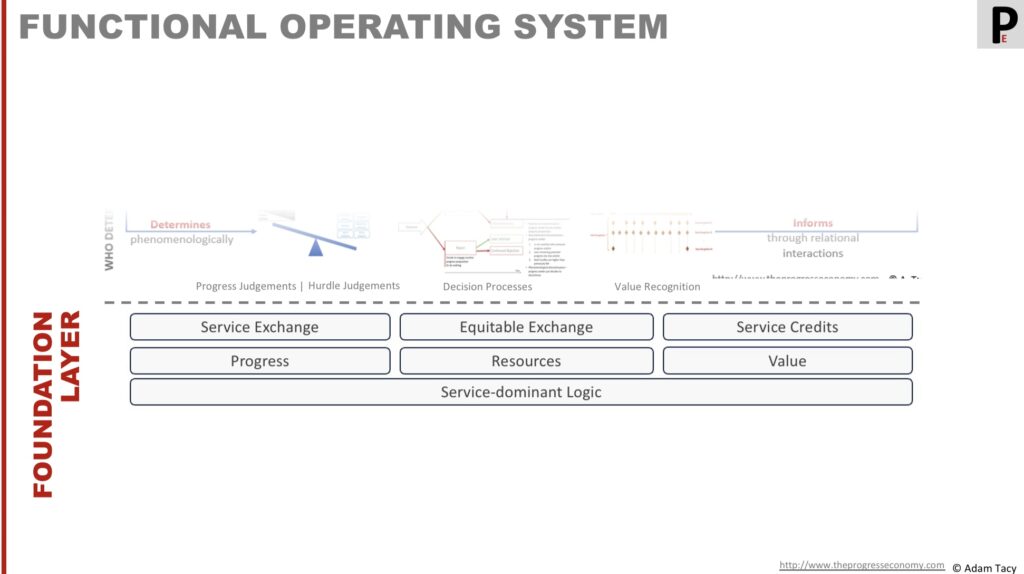

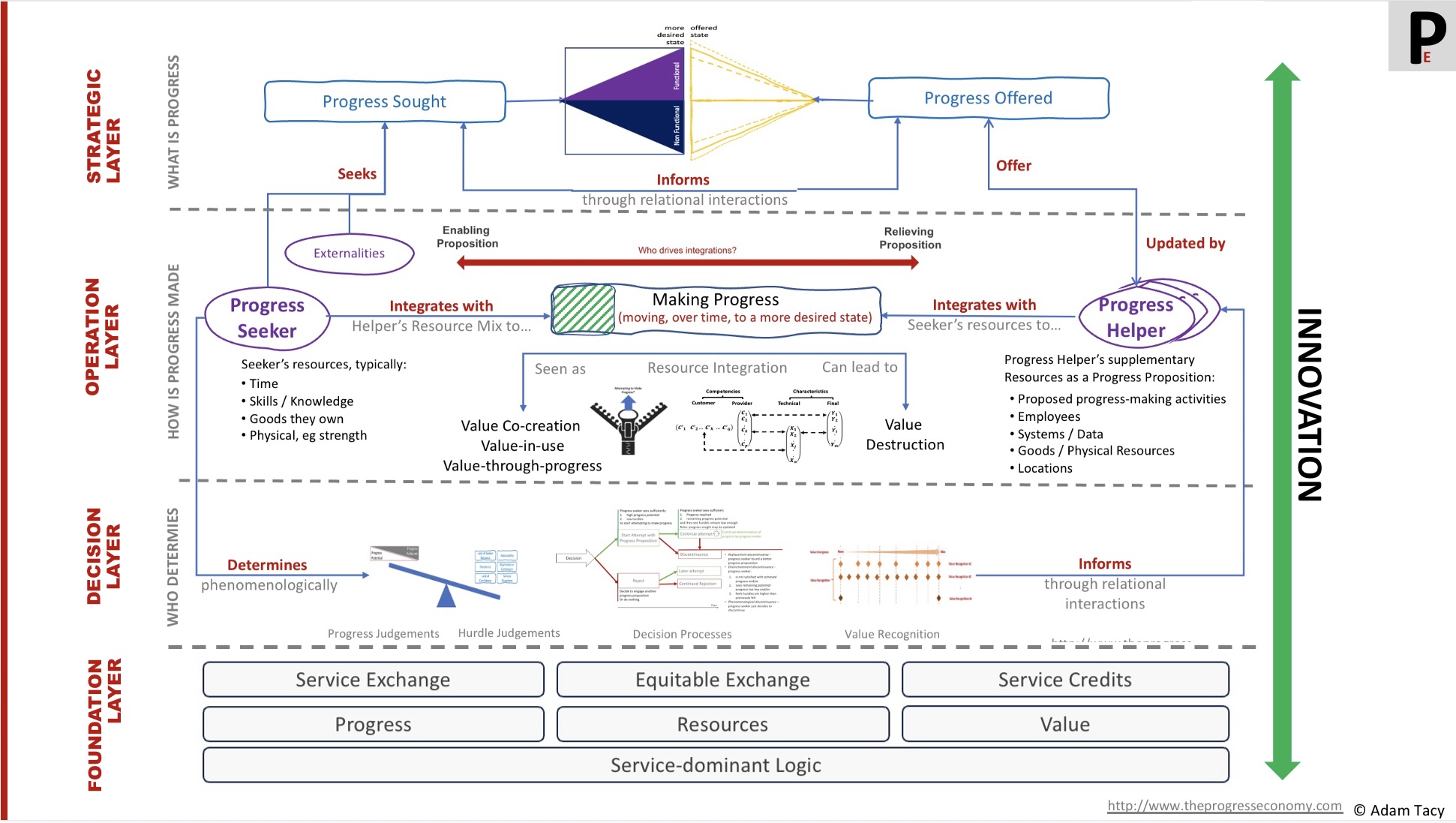

Here’s how the progress economy looks if we explore it as a functional operating system. It has four layers, each capturing distinct insights and exposing multiple levers we can use for more systematic and successful innovation (which we define as improving progress):

- Strategic – what is progress

- Operation – how is progress made

- Decision – how, and by who, is progress determined

- Foundation – what shoulders and definitions are we standing upon

This is one of the three, equally useful, architectural ways of looking at the progress economy.

Progress as an operating system

A functional operating system model gives us insights into how we see our world working at various levels of abstraction. This ultimately gives us deeper insights into the levers we have for innovation.

Viewing the progress economy as such, one of three architectural views, reveals four key layers:

- foundation layer – this covers the basics, including the underlying service-dominant logic and definitions of key concepts like progress and value.

- decision layer – captures the decisions made by actors, such as when they start or abandon a progress attempt and their judgments on progress potential, progress reached, why emerged value needs to be recognised, and the size of six progress hurdles.

- operational layer – focuses on how progress is made through resource integrations, the nature of these resources, the role of progress propositions, and how value emerges (co-creation, value-in-use, value-through-progress) and value destruction.

- strategic layer – involves understanding the seeker’s progress origin and progress sought, the relationship of those to a proposition’s progress offered and origin, segmentation, as well as exposing why understanding all aspects of progress (functional, non-functional and contextual) is important.

And within and across the layers we find the innovation levers we can use to improve progress made by progress seekers.

Let’s jump into each of these layers, starting with the strategic one.

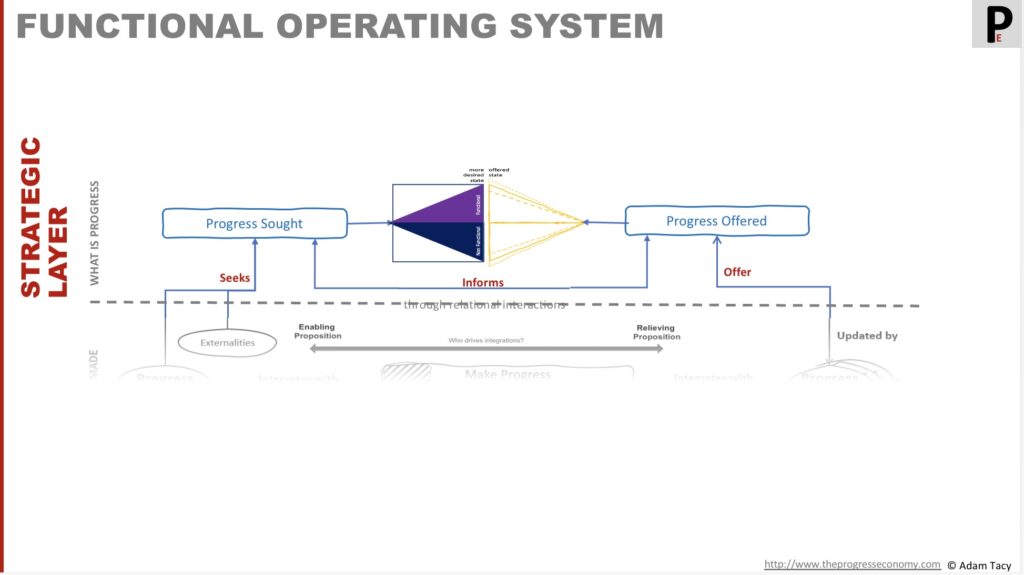

Strategic layer

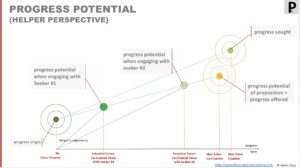

Understanding and leveraging progress origin, sought and offered is strategically essential. As is observing they evolve overtime due to seekers constant progress attempts and observation of others attempts (in your and other industry, markets, geographies).

Strategic Layer

What is progress?

Progress is the beating heart of the progress economy. We’ll define it later, in the foundation layer, as:

a move over time to a more desirable state

It’s a verb, state, state transition and noun encapsulating functional, non-functional and contextual elements.

Seekers look to make progress, helpers offer to help.

And this flows into our base definition of innovation – improving progress.

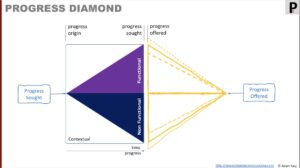

Navigating progress

In the progress economy we identify three strategic progress states; the progress:

- origin – the starting point of progress, as seen by actors (often differently):

- a progress seeker’s starting point for their progress attempt

- the point a progress proposition assumes a seeker is starting from

- sought – the more desirable state a seeker is attempting to reach

- offered – the state a progress helper is offering to help a seeker reach

Each of these states contain three equally important elements: functional, non-functional and contextual progress.

While “progress sought” encompasses all the progress a seeker wants to achieve in their life, we usually consider distinct aspects individually to keep things manageable.

It’s also important to note that a seeker’s origin and progress sought constantly evolve. They are influenced by all the other progress attempts they are making and observe others make; in both your market/Industry/geography and others.

Making progress

From a strategic view, a successful progress attempt involves the seeker moving from their current progress origin to their more desired progress sought state. That leads to the emergence, and recognition, of maximum value.

Seekers may attempt progress themselves or with the help of a progress proposition.

The decision to engage a proposition arises when seekers feel they lack necessary resources – such as time, skills, knowledge, or physical strength. Propositions help as they are bundles of supplementary resources that aim to reduce a seeker’s initial lack of resource.

Although now the end point is progress offered, which may differ from progress sought.

Helping progress

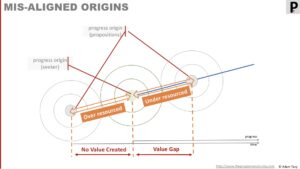

Ideally, a proposition’s origin and progress offered would match each seeker’s origin and progress sought across functional, non-functional, and contextual elements.

In reality, this alignment is uncommon.

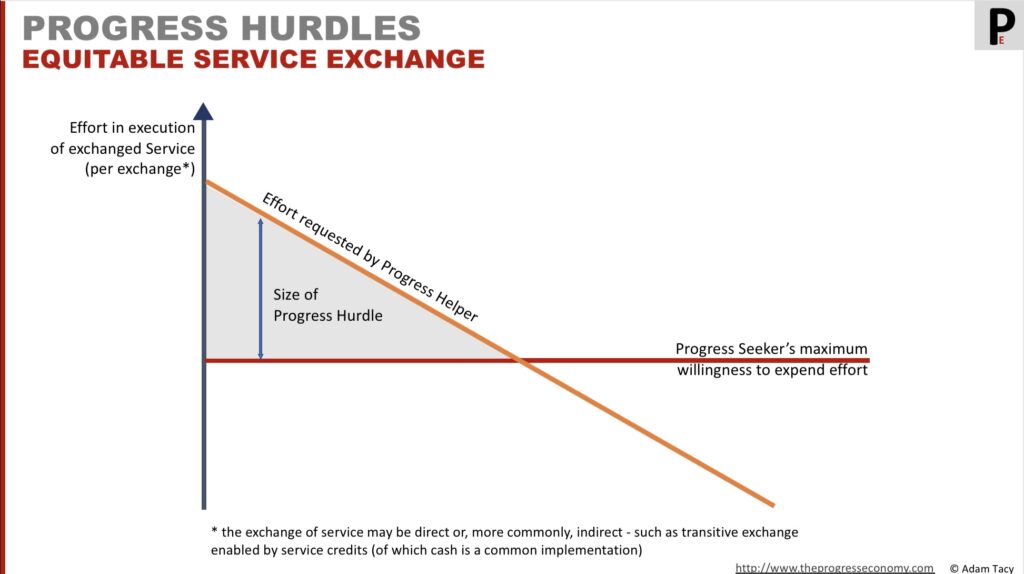

A precise match implies a lot of customisation. Which increases the effort a helper needs to put in. That gets reflected in the effort expected from a seeker in service exchange (we’ll come to this later – for now, let’s simplistically say this is price). Which in turn is visible as the equitable exchange progress hurdle – the higher the hurdle, the less likely a seeker will engage.

Helpers, therefore, tend to strategically position their proposition’s progress origin and progress offered to attract the maximum number of seekers whilst minimising the equitable exchange progress hurdle.

Such progress offered must be sufficiently close to a seeker’s desired progress sought to initially attract them to compromises on progress sought in return for a reduction in exchange effort.

Usually exchanges are indirect, mediated by service credits, of which money has been a successful implementation. We’ll come back to this in the foundation layer.

Additionally, the two progress origins should not be too far apart. If a proposition’s origin is closer to the progress sought than the seeker’s origin, the initial lack of resources may not be sufficiently addressed. Imagine trying to lear Mandarin Chinese in a class and the only class being for intermediate learners.

Conversely, if it is further away, the proposition risks offering wasted resources potentially leading to seeker frustration, value destruction, and an, in the eye of the seeker, unnecessarily increased equitable exchange demand. Imagine being required to take beginner Mandarin Chinese if you are at an intermediate level.

You might naturally see how these insight inform progress helpers about segmenting their market and offerings.

Segmenting help

Traditional market segmentation is based on product features, pricing, and/or demographics (age, sex etc), geographics, psychographics, behavioural etc.

Now the progress economy offers a better way: segmenting on progress origin and progress sought.

Strategically, a helper has three choices for their proposition. They can attempt to match:

- every seeker’s origin and progress sought (ie to be fully customisable)

- group seekers on similarity of progress sought and have a fixed proposition origin (segmented)

- group seekers on similarity of progress sought and progress origin (fully segmented)

The size of each segment, and number of segments is of course another strategic choice of the helper. As is whether the helper choses to have propositions for one or all combinations of segments.

Ultimately it is seekers that steer whether segmentation was correct by whether they engage or not.

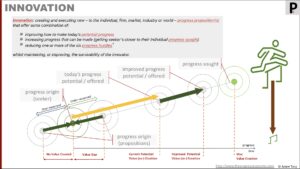

Innovating – offering better help

The strategic layer gives us the first insight into innovation in the progress economy. Innovation is about improving progress. From a helper perspective, that means creating and offering new progress propositions that help seekers progress better than before. It is some combination of:

- improving how to make today’s progress

- getting seeker’s closer to their progress sought

- moving the proposition’s progress origin closer to individual seeker’s origins

Helpers innovate to:

- increase the number of equitable exchanges they participate in

- expand the size of equitable exchange, or

- both.

They might alter their existing propositions to target different combinations of seeker segments (origins/progress sought). Or they might create parallel offerings targeted at different combinations of seeker segments. Which might involve bundling/unbundling amounts of progress.

Helpers might identify an unfilled gap in the progress journey they can offer to fill. Either expanding their current offering or creating a new independent offering.

Sometimes those gaps are adjacent to the progress a helper currently offers to help make. A case in point is when tyre company Michelin started publishing reviews of restaurants. That supported seekers’ progress of discovering new places to eat…which encouraged them to drive, wearing out tyres, leading to more exchanges for Michelin.

Alternatively, progress helpers might shrink their offering – moving their progress origin by removing unneeded resources; or reducing progress offered to affect equitable exchange (or another of the six progress hurdles).

As we look at the various layers, you’ll see how we add to this definition.

Needing innovation

One thing is for sure. Seekers’ progress origins and progress sought constantly evolve. Either from attempting progress or from observing others making attempts. Both in your current domain (industry/market/geography) and others.

This constant evolution of expectations needs to be addressed by progress helpers, otherwise propositions become increasingly unattractive to seekers. “Innovate or die”, it has been said.

However, there are risks to be aware of. Most famously, an incumbent helper chasing the more demanding segment of seekers is the source of Christensen’s Innovator’s dilemma. That potentially opens the market up for disruption when new technology arrives; but is also the opportunity for new comers.

So how is progress made? To explore that, we turnto the operation layer.

Operation layer

Seekers attempt to make progress by integrating resources together in a series of progress-making activities.

We call these progress attempts, since a seeker may succeed or fail to make progress.

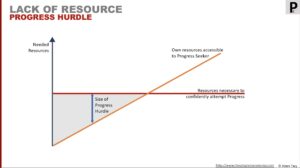

Lacking resource – for example time, skills, knowledge, or strength – is the fundamental hurdle to progress.

This is often addressed by engaging progress propositions, which consists of supplementary resources – proposed progress-making activities and a mix of resources to integrate with).

Operation Layer

How is progress made.

As resources are successfully integrated, progress is made and value emerges. Though value may also be destroyed through progress being hampered.

Innovation at this level is resource focussed – improving existing and offering new resources; organising resources differently; and improving progress-making activities (which are themselves a resource).

Who is involved?

The progress economy involves relatively few actors. We are all progress seekers, striving to make progress in all aspects of our lives.

Those offering to help us progress, through offering progress propositions, are called progress helpers. A seeker may engage one or more helpers when attempting to progress. The later being the case if propositions need to be strung together to achieve all of a particular progress sought.

Although sometimes a single helper might offer to act as a façade to other helpers – package holiday helpers, for example. Or they may allow seekers to choose from different helpers for aspects of progress sought. Online retailers often offer a choice of payment helpers and might offer the seeker a choice of delivery helper.

While seekers primarily define their progress sought, externalities – such as governments, trade bodies, and other institutions – also play a role. These entities impose laws, rules, standards, and expectations that are inserted into functional, non-functional, or contextual progress sought, regardless of the seeker’s intentions.

For instance, making progress relating to natural gas installation typically requires certified knowledge and skills as determined by laws.

Making progress – it’s all about resources

As we’ve discussed, a seeker may attempt progress themselves. In such a case, they execute a self-determined series of progress-making activities. These move them over time from their progress origin towards their progress sought.

Each activity involves the integration of some resources the seeker has available to them. With progress resulting from each successful integration and value emerging from that progress.

Although there is a special case when a seeker’s attempt involves finding effective progress-making activities. Here, even a failed activity can be considered progress, as it eliminates an unproductive path.

What are these resources? They include time, skills, knowledge, and physical attributes such as strength. Additionally, they are objects from a seeker’s environment that they can use or acquired through previous interactions with helpers.

Using resources

Fundamentally, we see resources as carriers of capabilities. You, for example, carry skills and knowledge, while a drill possesses the capability to make a hole, effectively freezing the manufacturer’s skills and knowledge in the tool.

Resources fall into one of two important categories:

Operant Resource

acts on other resources resulting in progress being made

Operand Resource

need to be acted upon for progress to be made

Operand resources need to be acted upon for progress to be made. These are the artefacts you find in your environment or the goods/tools you might acquire from helpers. Interestingly, you are sometimes an operand resource. For example when having a medical operation.

Conversely, operant resources act on other resources resulting in progress being made. Those other resources can be operand, operant or a mix. For example, you, as an operant resource, use a drill, an operand resource, to make a 1/4 inch hole.

Integrating resources

To achieve progress, at least two resources need to be integrated, with one being an operant resource (performing the integration).

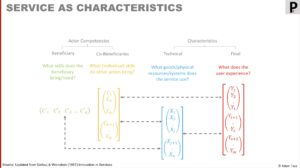

An effective way to understand these integrations is through Gallouj & Weinstein’s view of services as characteristics.

This model allows us to consider how actors’ competences (a combination of seeker and helper operant resources) integrate with operand resources to achieve specific outcomes, which we interpret as functional, non-functional, and contextual progress.

This framework covers all service modes: from self-service with no helper, to enabling services depending on seeker competence to utilise helper competence embedded in goods, and on to relieving services relying fully on helper competence, and on.

A significant challenge in our complex world is that seekers often lack the resources necessary to progress on their own.

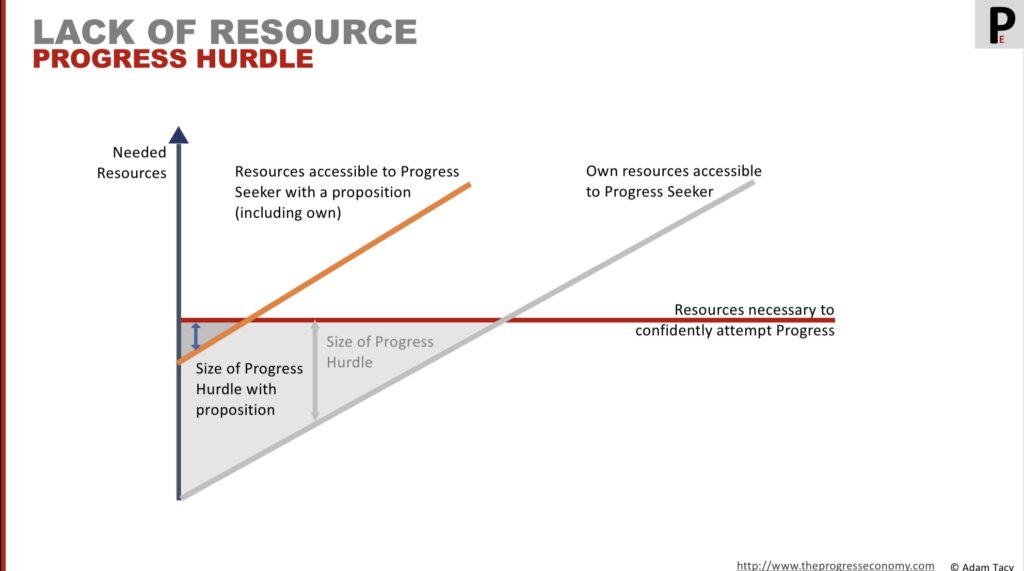

Lacking resource – the fundamental progress hurdle

You’ll recognise lack of resource: you don’t have the time, or you don’t know how to make progress. Maybe you know the necessary progress-making activities, but don’t have the skills, or other resources, to execute them. Or your order from IKEA is too heavy to carry home in your arms.

Looping back to our externalities example above, you might lack the qualification the law requires to install that new gas boiler. This is why we see externalities directly impacting progress sought rather than progress offered.

In the progress economy we see lack of resource as a hurdle, but not a barrier, to attempting progress. The distinction being a hurdle can be attempted, regardless – which is what we observe some seekers doing, and a subset of the successful ones turn their new found competence into propositions…

Helping make progress – offering supplementary resources

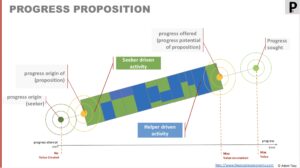

Progress propositions offer help to make progress. They do so by attempting to minimise a seekers lack of resource. As such, propositions comprise of two supplementary bundles of resource, a:

- proposed series of progress-making activities (which you might recognise better as instructions, manuals, processes, recipes, etc)

- proposition specific resource mix (some combination of employees, systems, goods, physical resources, data, locations)

These propositions exist on a continuum between enabling and relieving propositions, determined by who performs the majority of the progress-making activities.

Initially such a continuum might appear to address only a seeker’s lack of time. However, it gives deeper insights into which non-functional progress a proposition supports and the level of competence the seeker needs to engage.

Here we find an advantage of thinking in terms of progress. Focusing on progress rather than products broadens the solution space and encourages innovation. For instance, in gas boiler installation, a helper might offer a qualified employee as a relieving proposition, or offer training to enable the seeker. And there are option inbetween, such as varying levels of augmented reality, expert on a shoulder, or artificial intelligence offerings.

This concept of resource integration leading to progress has profound implications on how we see value.

(Co-) Creating value through progress

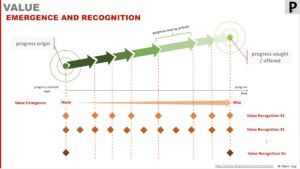

In the progress economy we observe that successful resource integration (use of resources) leads to progress being made towards a seeker’s more desirable state.

This signifies a shift in the value model we perceive. From value-in-exchange to value-in-use. In fact, in the progress economy, we take a further evolution of value model to what we call value-through-progress. Since progress is the predominant quantity and value follows

Further, emerged value needs to be recognised by a seeker – a process similar to revenue recognition in firms – for it to be meaningful to them. We’ll come back to this in the decision layer.

When a seeker engages a progress proposition, progress becomes a joint endeavour, leading us to refer to value being co-created.

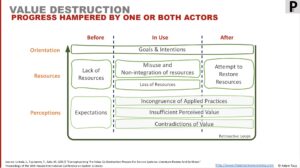

However, value can also be destroyed in progress attempts.

Destroying value

In the real world, progress can be obstructed by one or more actors, causing value destruction.

Lintula et al offer a helpful framework to understand where, when and why this may happen.

For instance, as a seeker, ignoring the instruction manual and misusing resources can derail your progress, leading to value destruction. Your chosen helper might not have the necessary resources when promised, or you might disagree with your helper’s values.

Here in the operational layer are several lavers for innovation.

Innovating – offering better resources

As highlighted in the strategic layer, innovation is about enhancing progress. Here are some practical aspects.

In the operational layer, innovation naturally revolves around resources and can be driven by either seekers or helpers.

A seeker may find better natural resources, use existing resources differently, observe and import progress from other industries/markets/geographies, or experiment with their progress-making activities.

Helpers can improve existing resources, or alter their resource mix, to offer today’s progress, but better (remembering that progress comprises functional, non-functional elements). Or they innovate to remove today’s constraints (captured as the contextual aspect of progress).

Another innovation approach is to move along the continuum. Typically we see this from enabling to relieving propositions. Which is driven by some well known reasons, grouped in goods-dominant thinking as “shift to service economy”.

Further still, the progress-making activities can be made more, or less, mandatory by altering how they are offered/performed. Wrapping them in a system’s process, for example, makes them more mandatory, less open to abuse, and therefore a potential mitigation to value destruction. However, care is needed as making things too mandatory can back-fire with seekers.

Now we’ll jump down to the decision layer, which we’ve already mentioned a couple of times.

Decision layer

Decision Layer

How, and by who is progress determined

In the decision layer we find the choices actors make in the progress economy.

Predominantly we see the seeker deciding on starting, continuing, and abandoning progress attempts. Making judgements on progress potential and progress reached (views on value) as well as when to recognise emerged value.

Though in some service, the helper makes similar decisions. Resulting in them making offered resources available or withdrawing them.

We’ll find that all decisions are phenomenological. That is to say are based on individual actor’s past baggage and their at-the-moment experience.

Additionally we find the progress hurdles, some of which we’ve already discussed. Helpers try (usually) to reduce them, and seekers’ judge their height. So let’s start there.

Judging progress hurdles

Our progress-centric world has a problem: there are hurdles to making progress.

We’ve already seen this. Fundamentally, a seeker may lack the resource necessary to make progress. Does the seeker have the time to attempt progress. Do they feel they possess the needed skills and knowledge? Do they know how to progress – that is the necessary progress-making activities? Maybe they lack physical attributes such as strength.

We call these challenges hurdles rather than barriers because seekers might still try to progress even with resource shortages. Discovering new progress-making activities or creating new resources might be part of the progress they seek!

Often, seekers turn to a helper’s progress proposition. These propositions are bundles of supplementary resources designed to address the initial lack of resources. However, they might not fully address the gap (resulting only in a reduced initial hurdle), might overcompensate (frustrating the seeker), or even introduce new lack of resource (such as skills/knowledge to use a new tool/system offered).

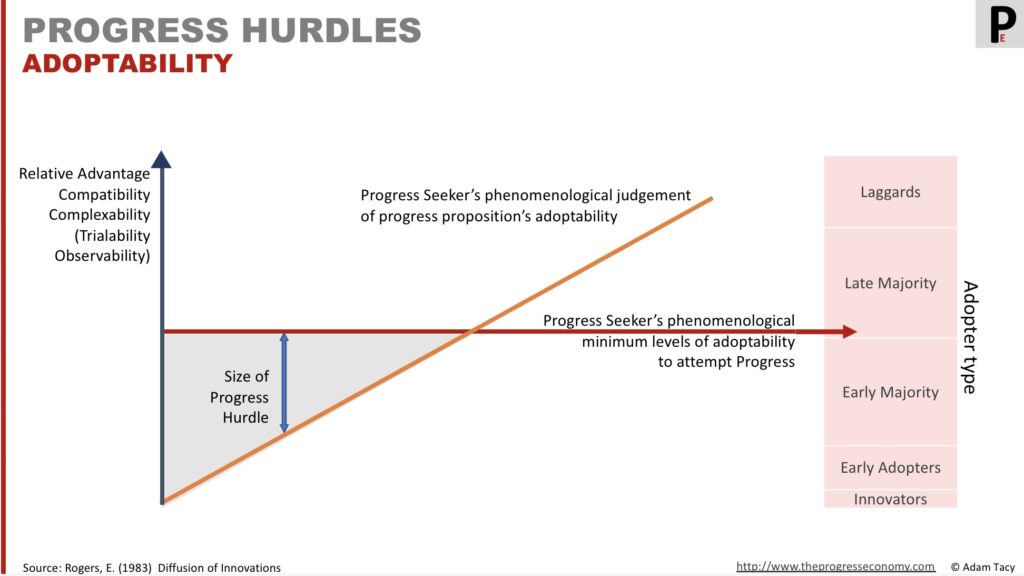

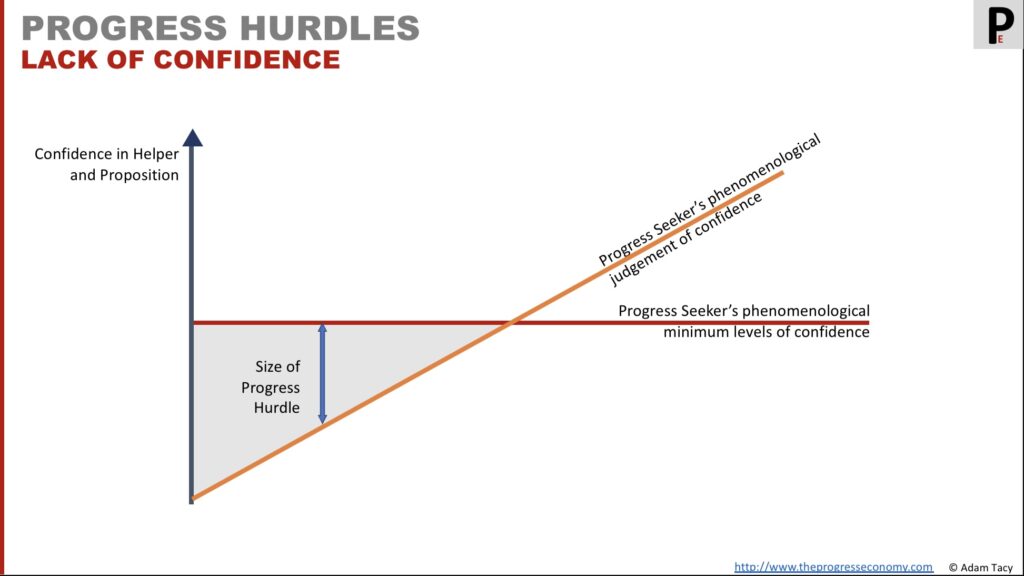

Whats more, propositions give rise to five additional progress hurdles:

- adoptability – Rogers’ original attributes from his theory of innovation

- resistance – there are several reasons seekers may resist innovations

- misalignment on continuum – seekers and propositions take places on the relieving-enabling continuum; the further apart those positions are, the higher the hurdle

- lack of confidence – seekers may not trust the proposition and/or the helper (links to marketing)

- equitable service exchange – this is deep, subtle and interesting…for now, we can loosely interpret as price

These hurdles look as follows.

Helpers naturally judge these hurdles as they usually wish to minimise them. Though one can argue that Snap make their user interface confusing to parents, pushing the adoptability hurdle higher; much to the delight of teens (their target seekers).

Seekers individually, and phenomenologically, judge these hurdles as part of their progress decision process.

Judging progress potential

Seeker’s individually, and phenomenologically, judge their progress potential as part of their progress decision process.

This assessment influences whether seekers decide to pursue progress independently or engage a proposition, as well as how they choose between different propositions.

Service-dominant logic – which we’ll come to in the foundation layer – tells us only the beneficiary (seeker) can determine value. But we’d be incorrect to assume that helpers do not judge progress potential (remember value emerges from progress, not progress equals value). They do so in two ways.

Firstly, they judge the potential of their proposition; this ultimately is better known as the progress offered (not price; see later).

Additionally, helpers may judge progress potential with a specific progress seeker, deciding to withdraw/not offer resources if they feel potential is too low. You might not be entertained by a Ferrari dealer, for example, if they phenomenologically decide you are unlikely to participate in an exchange for one of their cars (ie progress potential is too low).

Judging progress reached

The second judgement of progress in the progress economy is progress reached.

progress reached: the progress state that is phenomenologically judged to have been reached at a specific moment during a progress attempt.

Like progress potential, this is predominantly judged by a seeker. It may have real scalar values – such as kilometres made – or be measured on artificial scales – safety, for example, measured as number of incidents over a certain time.

Often this measurement represents value that has emerged. However, seekers convert that to recognised value for it to be meaningful to them. And recognised value often departs from emerged value, as we’ll see in the decision layer. Seekers use both views of progress reached.

Helpers may also sometimes judge progress reached when engaging a particular seeker. Deciding to withdraw resources offered if progress reached is not sufficient.

It’s interesting to note that both judgements of progress reached and potential feed into the concept of value destruction we saw earlier. As well as into our next topic: a seeker’s continuous progress decision process.

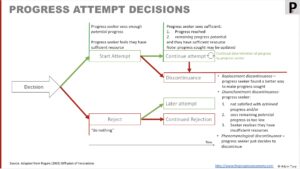

Deciding to start and continue making process

When attempting progress alone, a seeker follows a structured progress decision process. This is rather deliberately, similar to Rogers’ innovation adoption process (we see making progress as similar to adopting an innovation).

Seekers first decide whether to start a progress attempt based on their phenomenological judgement of sufficient progress potential and a manageable resource hurdle. They then continuously review these factors, along with the progress reached, to decide whether to continue or abandon their attempt.

Seekers abandon attempts for three reasons:

- disenchantment discontinuance: dissatisfaction with progress reached, remaining progress potential, or the lack of resource hurdle being too high.

- replacement discontinuance: found a better way to attempt progress.

- phenomenological discontinuance: simply feeling like abandoning the attempt (maybe another aspect of progress has become more important to them)

These judgements are naturally made by seekers at the end of each progress-making activity, though seekers may make them earlier.

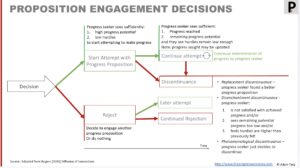

When a seeker engages a progress proposition, this decision process evolves into the engagement decision process.

Deciding to start and continue engaging a proposition

As seekers look to engage propositions to aid their progress, their decision process evolves to take account of propositions (rather than just “do nothing”).

The basic process stays the same, but seekers might choose not to start an attempt if they find a better proposition. “Better” could mean some combination of:

- getting closer to their progress sought (increasing progress potential)

- starting nearer their progress origin (also increasing progress potential)

- being able to make current progress potential in a better way

- lower progress hurdles

This could of course be a decision that progressing alone is best, despite their being available propositions.

The continuous decisions to continue similarly takes into account all six progress hurdles. Along with seeker’s judgements of progress reached and future progress potential. And we find the same three reasons for abandonment.

The final decision seekers take is that of recognising value.

Recognising value

Lastly, but not least, the seeker needs to recognise value that has emerged, for it to be meaningful to them.

It helps us understand whether progress has been valuable. Does, for example, making 80km of a 100km journey give any value to the seeker? It depends on the totality of progress sought. For some, they can rest and continue the next day – they might recognise 80 units of value. For others, not making the 100km by a set time means the attempt was worthless.

Innovating – improving decisions

In this layer, innovation aims at influencing decisions.

From a helper’s standpoint, can we boost seekers’ initial judgments of progress potential and lower their initial assessments of the six progress hurdles? Can we enhance judgments of progress reached and remaining potential during the attempt? Can we increase the frequency of value recognition?

This means influencing how and when seekers make these judgments. Suggesting a more effective measuring scale; increasing frequency of interactions, etc.

Can we alter our proposition dynamically to react to a seeker’s new found challenges in progressing?

I’m sure you can think of more examples.

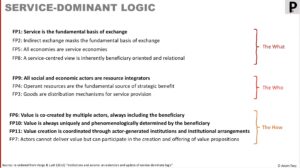

Foundation layer

Underlying the above three layers are a strong influence of Vargo & Lush’s service-dominant logic and our definitions of the progress economy’s fundamentals:

We also find definitions of service and service exchange, which are mediated by service credits.

It’s in the later we find business model innovation.

Foundation Layer

What is the progress economy built upon?.

Introducing service-dominant logic

Vargo & Lush’s service-dominant logic is an evolved way of looking at value creation. Instead of value-in-exchange they talk of value-in-use/context. This removes an aspect that gives rise to several blind spots in our traditional value-in-exchange view of the world.

Ultimately, service-dominant logic arrives at 11 foundational principles (five of which are axiomatic).

And it is from these we build-out the progress economy.

- Service is the fundamental basis of exchange

- All social and economic actors are resource integrators

- Value is co-created by multiple actors, always including the beneficiary (seeker)

- Value is always uniquely and phenomenologically determined by the seeker

- Value creation is co-ordinated through actor-generated institutions and institutional arrangements

Varying from service-dominant logic

We drift a little by recognising seekers can make progress on their own and that helpers sometimes also determine progress. And we fundamentally shift concept to one of making progress, from which value emerges (and needs to be recognised by seeker to have meaning).

Defining the basics

We arrive at the following definitions:

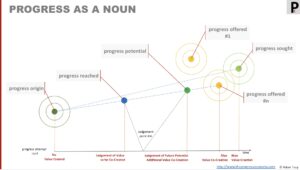

progress: moving over time to a more desired state

Where we come to view progress in four ways, progress as a:

- verb – the above movement over time

- state – a snapshot of progress in time, comprising three elements: functional, non-functional and contextual

- state transition – an alternative view of progress as a verb

- noun – some named states that help us better navigate progress attempts – progress origin, sought and offered – and progress judgements – progress potential and reached.

Having defined progress, we can now define value:

value: i) a trailing metric of progress made (which needs to be recognised by a seeker in order to be meaningful)

ii) a view of potential progress that could be made

Our model of value follows this definition. We evolve from our traditional model of value-in-exchange to value-in-use (as part of the service-dominant logic foundations).

Doin so addresses several blindspots to growth and innovation. However, we evolve one step more by recognising value is a trailing perspective (it emerges from progress) to value-through-progress, the foundation to the progress economy. Now we have the definition and levers to better drive innovation.

Rounding off our basic definitions brings us to the important resources.

resources: carriers of capability

Where we explore what capabilities are and why thee’s some confusion brought about by loose terminology!

Handling service

Since our foundation is based on service, we define that as:

service: application of resources in order to make progress

We use “service” (singular) as a perspective on value creation rather than the product category of “services” (plural) (Edvardsson et al. (2005) “Service portraits in service research: a critical review”).

And in the progress economy, service rather than value is exchanged (axiom #1 of service-dominant logic).

Exchanging service

This leaves us with a little challenge to explain price, the role of money, and, that we don’t often see service exchange (reciprocal application of resources).

Vargo & Lush already solved the later matter by identifying that indirect exchange often masks the service exchange nature of the world. We explore that a little further, usefully identifying types of indirect exchange, for example: transitive indirect exchange.

Here service credits are used to lubricate exchanges as well as to mediate temporal and magnitude differences in service effort.

Which brings us nicely to price. Since we no longer exchange value, price must indicate something other than that. In the progress economy it represents the effort a helper expects to receive in service for the effort they are giving.

Innovating in service exchange – business model innovation

Exchanged service effort can be provided directly in service or through service credits, or a combination.

It may come from the seeker or elsewhere – opening the door to business model innovation (subsidised, freemium, alternate payments (loans, delayed payments and so on) etc). And since service occurs over time, service exchange may also occur over time (subscription models, etc).

Key take-aways

- The progress economy can be explored through a four layer hierarchy, with strategic, operational, decision, and foundation layers.

- In the foundation layer we identify that value follows from progress, and so progress must be our key focus rather than value. This has profound implications for how we see the world operating and what decisions are being made.

- Progress can be attempted by a seeker on their own. Here they integrate the resources they currently have available to them. However, they likely find the lack of resource progress hurdle is too high.

- Progress helpers offer propositions – bundles of supplementary resources – aimed at helping a seeker progress (reduce the lack of resource progress hurdle and/or increase seekers judgement of progress potential). Only now the destination is the proposition’s progress offered rather than the seeker’s progress sought. Seekers must judge if that is close enough.

- Propositions introduce five additional progress hurdles that must be sufficiently low enough for the seeker to engage the proposition in a progress attempt. These are: adoptability, resistance, misalignment on continuum, lack of confidence, and equitable exchange. They also may not sufficiently lower the original lack of resource hurdle; and may even introduce new lack of resource.

- As progress is made – resource integrations are successful – value emerges. For that value to be meaningful to the seeker, they must recognise it. This is akin to revenue recognition in firms.

- Innovation is all about improving progress, and it applies to all layers in the hierarchy. Within each layer there are tools and levers to support more systematic innovation.

Let’s progress together through discussion…