What we’re thinking

Progress attempts are how seekers reach their individual progress sought.

They’re a tale of progress-making activities, resources, resource integrations, judgements of progress, progress hurdles; success and failure. Expanding on the concepts of progress, and, that value emerges from that.

Let’s explore here how a seeker attempts to progress (which forms the foundation of progressing with the help of a progress proposition).

Progress attempts

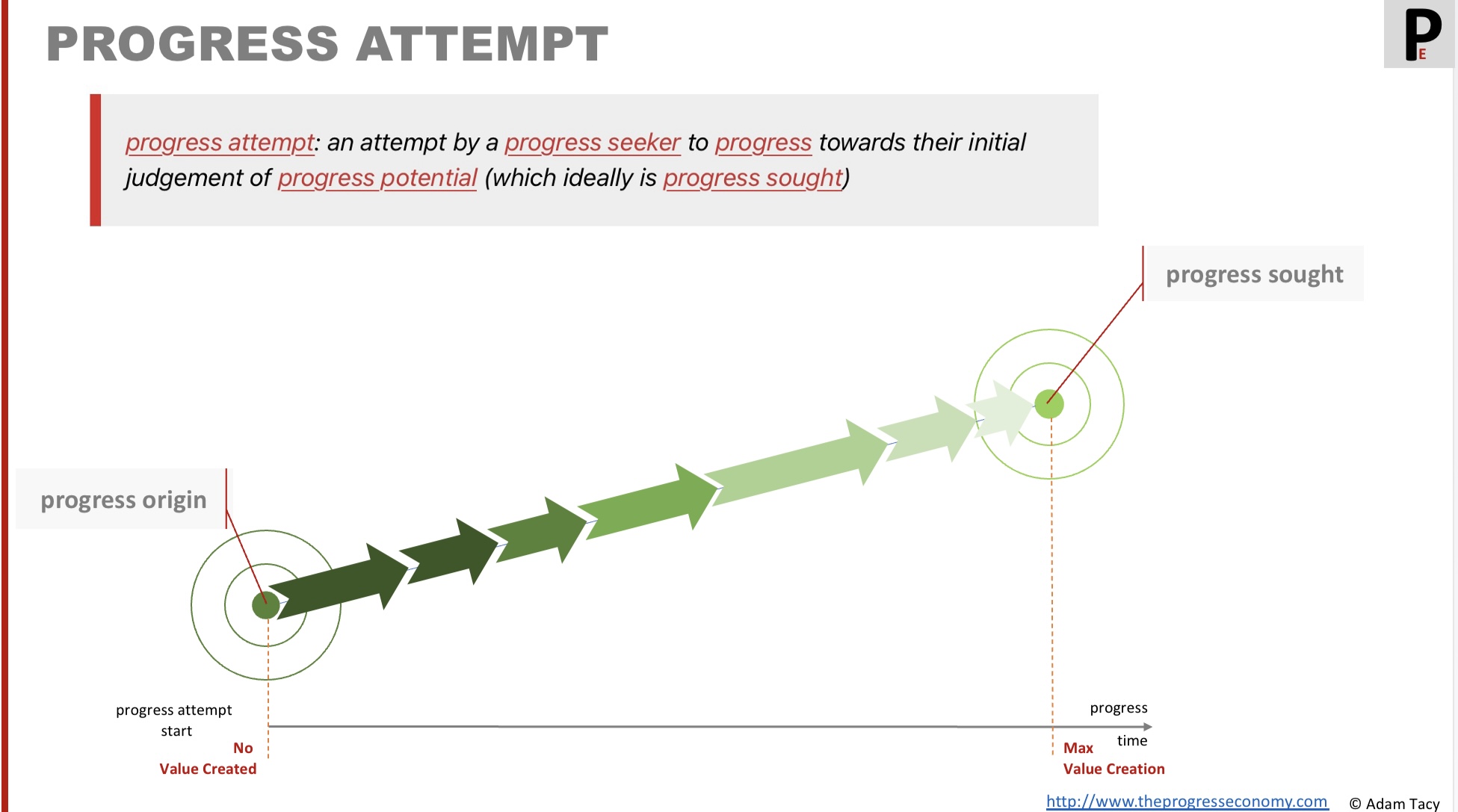

A progress attempt is the executional view of progress as a verb. That is to say, how progress seekers reach their more desirable state of progress sought from their progress origin.

progress attempt: an attempt by a progress seeker to progress towards their progress sought through executing a series of progress-making activities

Here’s a visual comparison between progress (as a verb) and a progress attempt.

Seekers attempt to make progress by executing a series of progress-making activities. Where each activity is a resource integration between resources the progress seeker has access to.

A successful integration moves the seeker one step closer to their progress sought.

However we deliberately call this an attempt since a progress-making activity may be unsuccessful – the integration of resources may fail. Sometimes the seeker will use their available resources incorrectly. Often the seeker lacks one or more required resources to progress – skills, knowledge, time, some tool, a physical attribute like strength, and so on. This is a progress hurdle and we call it: lack of resource. It might even be that the lacking resource is not knowing one or more of the progress-making steps.

To address a lack of resource, a seeker may decide to engage a progress helper’s progress proposition to attempt progress. In which case, progress becomes a joint endeavour. But that’ss a story for another time.

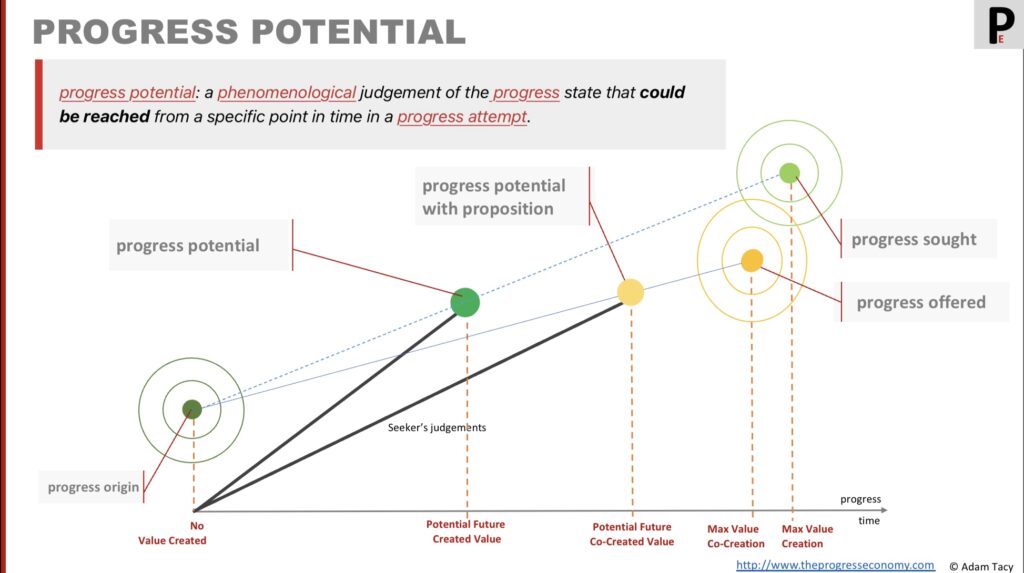

We also find that seeker’s continually make unique and phenomenological judgements of progress potential and progress reached during a progress attempt. These feed into a progress decision process to start and continue progress attempts.

Putting in context

Progress attempts inherit our concepts of progress and value. They add the notion of resources – carriers of capability – in both operant and operand form. As well as introducing the fundamental progress hurdle of lack of resource.

Let’s explore these three concepts of progress-making activities, resource integration, and the progress decision process.

Progress-making activities

Progress is made incrementally in steps.

For instance, when learning a language, we incrementally acquire and use sounds, symbols, words and grammar specific to that language. Similarly, traveling a distance requires physically moving from one point to another, km by km, town by town. Even hanging a picture on a wall follows a clear progression from an empty wall to attaching a fixture and finally placing the picture.

We see a seeker making such progress by performing a series of progress-making activities. Where each activity is an integration of resources.

progress-making activity: A resource integration activity that increases a seeker’s progress reached towards progress sought.

Successful resource integration means a seeker moves a step closer to their progress sought (simultaneously increasing their judgement of progress reached).

A seeker integrates resources they have access to. For example operant resources like their existing skills and knowledge; or operand resources like physical items they find in their surroundings or have acquired from previous engaging with a progress proposition.

We’ll later see how this pool of resources increases with progress propositions. They aim to address a seeker’s lack of resource (time, skills, knowledge, etc) with supplementary resources. Including proposed progress-making activities.

You might feel this “series of activities” is a little abstract. In daily life we know them under various more common names: action lists, instructions, plans, recipes, experiment design, etc.

Determining the activities

There are two ways a seeker attempts progress. Firstly they follow direct progress-making activities determined in advance. These may come from their experience, observation, or borrowing from some other domain experience they have.

Alternatively, a seeker’s activities define an exploratory approach. At the one end this could be pure trial and error deciding the next step after attempting a current step. Or, at the other end, the exploration could be more structured, such as the Agile methodology.

In both cases the progress-making activities are examples of operant resources (resources that act upon other resources to make progress). They are encapsulations of skills and knowledge.

As such, our service-dominant logic foundation tells us they are a source of strategic benefit. Which in common language means the better the activities are, the better the seeker feels they make progress. What does better mean? It’s a unique and phenomenological decision by the seeker, usually tied to non-functional progress they are seeking (quicker, safer, reducing anxiety, self-actualising,…)

It’s not uncommon for a seeker to not know the series of progress-making activities. Or to not know the necessary order. This is a lack of resource that progress helpers look to help with in their progress propositions.

We observe that the younger a seeker is (or newer to a particular domain) the more likely they are to lack knowledge and skills of the progress-making activities. That’s why we rely so much on progress helpers such as parents/elders and subsequently school and training to gain this operand resource.

But learning and training should encourage and enable structured exploration – otherwise we might fail to know how to make progress in new areas (a basis of innovation).

Resource Integration

Resource integration is simply the act of applying one resource to another. With the intention of making progress.

resource integration: the act of applying one resource to another resource with the intention of making progress

Some simple examples:

- A carpenter (a resource skilled in wood working) joins two pieces of wood together with a nail by integrating their knowledge and strength with a hammer (force multiplying capability) and a nail (joining capability).

- You (skills, knowledge and strength capability) cycle a bike (transport capability) to move to another place.

- A teacher (teaching capability) teaches a student (learning capability) to speak Mandarin Chinese.

Let’s note that resources have no value in isolation. When doing nothing, they are not contributing to making any progress. Resources have only potential to help make progress (from which value emerges). And we release that potential through integration with other resources.

Back to our simple example above. When not being integrated, the carpenter, teacher, hammer, nail, bicycle and you are making no progress; and so not creating value.

Our foundation of service-dominant logic tells us that all social and economic actors are resource integrators.

All social and economic actors are resource integrators

#9

Which in practice for the progress economy means progress seekers and progress helpers (who we’ll meet when looking at progress propositions.

Resources

Resources themselves are carriers of capability (Peters et al (2014)) as we point out in the above examples.

resource: a carrier of capability that can be integrated in one or more progress-making activities.

We differentiate resources into two types – operant and operand – depending on how they are involved in making progress.

Operant Resource

acts on other resources resulting in progress being made

Operand Resource

needs to be acted upon for progress to be made

And different combinations of resources can be integrated, although one of the resources needs to be operant. By definition, 2 operand resources cannot integrate with each other (without an operant resource acting upon them).

In the examples above, you, the carpenter, the teacher and the student are operant resources, whilst the hammer, nails and bicycle are operand resources.

Deciding to attempt Progress

Seekers, consciously or unconsciously, go through a decision process when initiating and continuing their progress attempts. Here’s how we visualise that:

This may look familiar if you’ve studied innovation before. It shares similarities in structure with Rogers’ innovation adoption decision described in his book “Diffusion of Innovations“.

And this is no accident. Each progress attempt is akin to adopting an innovation.

A seeker first needs to decide to start the attempt. Then they continuously evaluate if they will continue or abandon their attempt as they progress over time. Where the natural points for making continuation decisions are the end of each progress-making activity.

Seekers may choose to abandon their attempts (referred to as discontinuance in Rogers’ terminology). Discontinuance can occur due to a disenchantment when the above factors are not met, or it can be a replacement discontinuance if the seeker discovers a better way to make progress. Lastly, a phenomenological discontinuance, not part of Rogers’ thinking, happens when the seeker stops simply because they feel like stopping.

Their judgements are unique and phenomenologically to them. And relate to the progress potential, progress reached and their available resources (or rather, lack of resource – a progress hurdle).

We look at this in detail in the progress decision process. When a progress proposition is involved the decision process is expanded to cover the additional progress hurdles they introduce.

What is a successful attempt?

It’s quite interesting to ask the question “what is a successful attempt?”

Ideally, seekers aim to reach their progress sought (their more desired state) since that represents maximum value for them. So the simple answer is that success means reaching progress sought.

However, practical experience tells us that reaching progress sought in all aspects of life is a lofty, but ultimately unrealistic, aim.

We find that as seekers we evaluate our initial progress potential. Even if that is less than progress sought, we might judge it sufficient to start attempting progress. If we reach our initial judgement then the attempt is a success. Although we may wish to find how to increase potential for the next time.

Here’s a way to visualise this which we discuss in detail as we explore progress potential.

(the diagram also tells us that we expect engaging a progress proposition has the effect of increasing the initial judgement of progress potential).

Relating to value

When we explore progress as a verb we find that value emerges through progress. With no value being present at progress origin and max value having emerged upon reaching progress sought.

Now we can add to that story by saying value progressively emerges from performing successful resource integrations in a series of progress making activities.

That brings us to the same conclusion as Payne et al in their paper on “Managing the co-creation of value”, as well as givng an explanation why:

The customer’s value creation process can be defined as a series of activities performed by the customer to achieve a particular goal.

Payne, A. F., Storbacka, K., and Frow, P. (2006) “Managing the co-creation of value”

In the progress economy we additionally recognise that emerged value needs to be recognised by the seeker in order for it to be meaningful. The roots of this are in the progress decision process. Where seekers judge to continue or abandon progress attempts and if initial judgement of progress potential is sufficient to them.

What if a seeker makes a failed resource integration? Well, now we see the seeds of value destruction – where progress is hampered due to incorrect resource usage. Lintulla et al expand a little on this providing other reasons for value (co-) destruction. And a seeker can try and recover or abandon an attempt due to this.

Relating to innovation

The driver of innovation in a progress attempt is two-fold.

Firstly, our exploration of progress shows us that a seeker’s progress origin and progress sought are constantly evolving due to experience and desires. Secondly seekers will always look to increase their initial judgement of progress potential and get closer to their progress sought.

They both require a seeker to upgrade their resources including the progress making activities. In other words, they need to innovate (or find a proposition). How? Through some combination of

- using existing resources in different ways

- acquiring new resources from nature

- observing and copying other actors

- altering their progress-making steps

Seekers that successfully find a new way to make progress may decide to offer their new found resources to others. They become a progress helper with a progress proposition.

Let’s progress together through discussion…