Rather than pushing product features and value, anchor your thinking and organisation on delivering progress. By building around Seekers’ progress sought, progress origin, and minimising progress hurdles, you outperform on innovation, sales and growth.

What we’re thinking

Imagine a world where innovation lands, sales resonate, and growth accelerates – not because we focused on value, but because we focused on progress. We realise that value emerges from a set of progress comparisons. But what exactly do we mean by progress?

Progress – deceptively simple, deeply powerful – is the beating heart of the progress economy. We’re all trying to make progress in every aspect of life: with our bodies, possessions, mental state, information, and intangible assets. We seek to get fitter, move faster, fix things, learn more, travel, reach goals – or simply get through the day more effectively. Progress is everywhere.

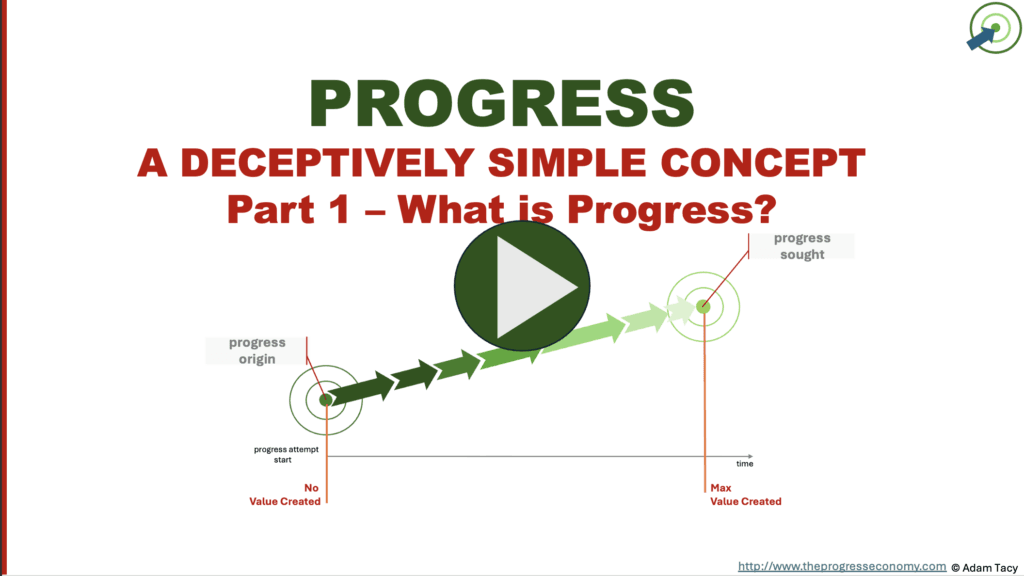

So, let’s define it clearly:

progress: moving, over time, to a more desirable state

By shifting our orientation from value to progress, we unlock new levers for innovation, sales, and growth.

To truly harness this, we must explore progress in five complementary ways, progress as a:

- verb – the act of moving, over time, to a more desired state

- state – made up of functional, non-functional and contextual elements

- measure – judging amounts of progress made/possible

- noun – naming the useful progress states on the progress journey

- state transition – another useful way of observing progress similar to being a verb

This framework reveals the engine behind everything from Jobs-to-be-Done and Christensen’s Innovator’s Dilemma, to Blue Ocean Strategy, Drucker’s innovate or die, Levitt’s warning of marketing myopia, the logic behind Agile, and how to minimise the blind spots in our traditional value-in-exchange model (such as circularity); and much more.

Yes, progress is complex – but not in a burdensome way. It’s structured, learnable, and far less abstract than it might first appear.

In short, progress gives us the clarity and tools to design better innovations, craft sharper go-to-market strategies, and build offerings that resonate more deeply with the people we serve.

What is progress

Progress is a lens through which we can understand the world – unlocking insights, solving the innovation problem, driving sales performance, and accelerating growth. It’s the horse that pulls the value cart. Yet too often, we put value before progress.

Conceptually, we’ll define progress as:

progress: moving, over time, to a more desirable state

What does this mean? We are all progress seekers. Every thing we do in life is an attempt to reach a more desirable state – whether that is becoming fitter, learning a new language, transporting something, increasing wealth, etc. A useful way of adding some more meat to the bones is to adopt Lovelock & Wirtz’s four categories of service. We seek to make progress with our:

- bodies

- possessions

- minds/mental state

- information/intangible assets

These categories help us frame what we’ll call functional progress. But, as we’ll see, progress extends beyond the functional. We also need to understand its non-functional and contextual dimensions. As an aside, we’ll often find overlap between service (singular) – “the act of applying your skills/knowledge for someone benefit” – and progress.

While progress may seem like a simple concept, that simplicity is deceptive. It underpins a rich operating system for understanding how our world works. One we can leverage to solve our challenges in innovation, sales, and growth.

Deceptively simple; Deeply powerful

The simplicity of progress – moving to a more desirable state – belies a deeper explanatory power. It reveals the underlying mechanics of our economy:

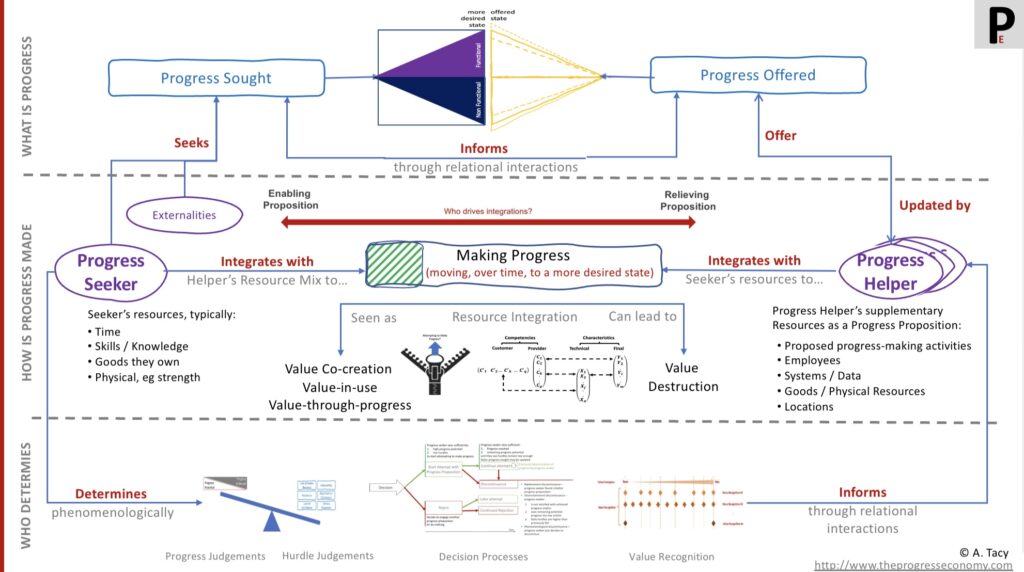

- we are all progress seekers, striving to move to more desirable state (progress sought) with every aspect of our lives

- we make progress attempts, a series of progress-making activities, integrating capability-carrying resources

- often we struggle to progress due to lacking capability – time, skills, knowledge, tools, physical attributes, etc. This is the foundational progress hurdle

- some of us seekers persevere, despite the hurdle, finding and/or developing new capabilities carried by resources in the process.

- some of us that have succeeded may then offer our new resources to help others – we become progress helpers, offering a progress proposition(s) to help other seekers reach a particular state of progress, from a particular starting point.

- progress propositions are bundles of supplementary capabilities intended to reduce a seeker’s foundational progress hurdle. These bundles consist of:

i) a set of proposed progress-making activities (manuals, instructions, menus, guided workflows…)

ii) a tailored mix of resources carrying the needed capabilities – employees/AI, systems, data, goods, physical assets, and locations - propositions introduce 5 new progress hurdles: adoptability, resistance, lack of confidence, continuum misalignment, and inequitable exchange

- helpers are not, usually, altruistic in providing help – they do so in exchange for help making progress of their own (we are all progress seekers) – though:

i) this exchange is often indirect

ii) indirect exchange is lubricated and mediated through service credits, of which money is a dominant implementation. - exchange is “measured” in effort, signalled by price, and needs to be felt equitable by all parties

It’s the unbalanced distribution of resources in the world that drives exchanges and the economy. Though let’s be clear, we’re not talking about a barter economy. Price, supply-demand, profits…these all have a place in the Progress Economy.

We can view progress through both a four-layer operating system and as a nested set of contexts. Both reveal levers for innovation, sales, and growth.

Progress as an operating system

Our view of progress helps us see an operating system of how the world works:

Putting progress in the strategic context

Progress is the base context of our layered Progress Economy context.

It’s where we conceptualise progress through five complementary ways, as a:

- state – snapshotting progress’s functional, non-functional and contextual elements

- verb – moving over time to a more desired state

- measure – judging amounts of progress

- noun – naming key moments on the journey

- state transition – observing shifts from one state to another

And find that value emerges from progress comparisons.

OK, let’s quickly explore the five perspectives on progress, linking to deeper investigations; starting with progress as a state.

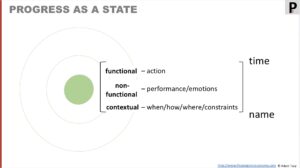

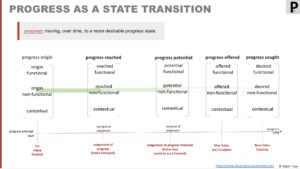

Progress as a State – snapshotting progress

A progress state – such as the more desired state a seeker wishes to move to – is a snapshot of three equally important elements of progress:

- functional – the objective aspect of progress

- non-functional – subjective aspect of progress (performance, emotional experience)

- contextual – constraints and situational variables

Functional progress is the element of progress you most likely think of. For example have ran a half marathon, arrived in Oslo, learnt Mandarin Chinese to HSK level 5, increased wealth, recovered from an illness, etc. Since it is a snapshot, it will be different at different times. Before having ran a half marathon, you might never have ran before.

Non-functional progress accompanies functional progress. This includes how one wishes to experience the journey—quickly, safely, easily, enjoyably, flexibly. Perhaps the seeker values autonomy, or the emotional reward of a sense of achievement.

To structure thinking around non-functional dimensions, we can draw on the hierarchy of value developed by Almquist, Senior, and Bloch. Many of their value elements map directly to non-functional aspects of progress

Contextual progress captures the environment in which progress is attempted. Conditions like “in rush hour” or “no driver’s license” fundamentally alter the nature of a progress attempt. As Christensen rightly observed:

A job can only be defined – and a successful solution created – relative to the specific context in which it arises

Christensen, C (2016) “Competing against luck”

Ignoring context strips meaning from progress. It’s not just what progress is being sought, but under what conditions it must be achieved.

Sometimes the boundaries between progress elements blurs. A simple way to think about it is this way. During a progress attempt:

- functional – always changes

- non-functional – may change

- contextual – never changes (by convention)

What happens when you misunderstand, or don’t recognise, non-functional or contextual elements of progress from a Seeker’s perspective? Supermarket self-checkouts. They support the functional progress of “buying groceries.” But they often ignore non-functional needs like ease, clarity, and stress-free interaction. And they make a contextual assumption that “everyone just wants to check out faster.” The result? Pushback, avoidance, and even resistance behaviours such as shoplifting. Some supermarkets are now returning to staffed checkouts.

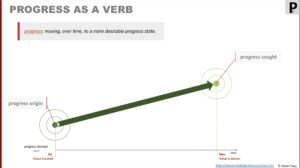

Progress as a Verb – moving from one state to another

Progress as a verb reflects action – resource integrations – that result in a seeker moving from one progress state to another. Specifically, a seeker is trying to move from their current state (progress origin) to their more desirable state (progress sought).

They make this journey through a progress attempt – a series of progress-making activities. Each activity is one or more resource integrations involving:

- Seeker’s time

- Seeker’s knowledge and skills (including of the progress-making activities)

- Tools/goods the seeker currently has available to them

Often, seekers lack resources to make progress. Thy may not have the skills, knowledge, tools, etc. Some persevere anyway, creating new resources along the way, others chose to engage a progress proposition offered by a progress helper. These propositions are two bundles of supplementary resources:

- proposed progress-making activities

- progress resource mix – employees, systems, data, goods, physical resources, locations

Progress becomes a joint effort: the integration of resources from both the seeker and the helper.

The degree to which the seeker or the helper performs these integrations places the proposition on a continuum:

- If the seeker does the work, the proposition is enabling

- If the helper does the work, the proposition is revealing

Every proposition has both an origin state, from which it offers to help from, and a state it offers to help reach. These may or may not align directly with the seeker’s own starting point or desired progress. The seeker decides whether the match is sufficient, ie they can make sufficient progress with the help of the proposition.

Some things to note on progress journeys:

- Contextual progress – we make the convention this does not change during a journey. If context needs to change, it should be reframed as functional/non-functional progress in a separate journey. For instance, overcoming a “have no driver’s license” constraint in a travel related progress journey can be reframed as a separate functional progress of “gain a driver’s license.”

- Non-functional progress – can either remain consistent (e.g., doing something safely) or increase over the journey (e.g., a sense of achievement increases over time).

- Missing functional progress – it is possible to define progress where there is no functional progress.

Progress as a Measure – judging amounts of progress

How much progress has been made—or could still be made? These are natural questions once we consider progress as a verb: starting in one state and moving toward another.

Predominantly, the Seeker is the judge of these. And these judgements are phenomenological. Meaning that they are based on the baggage the Seeker brings to the decision point as well as the current living experience they are having. It’s why you might find a supermarket self-service check-out really useful on a rushed Monday lunchtime, when it’s raining outside and you have 2 items to buy before getting back to finish off that report; whereas you can’t stand them on your weekly shop. Or why your one friend loves them all the time, but your other friend won’t use them out of principle.

In some propositions, Helpers may additionally judge progress, withdrawing their resources if they determine that insufficient progress is being, or likely to be, made. Consider a high-end car dealership where they don’t allow just anyone off the street to tie-up salesperson’s time.

In fact, such judgements are fundamental to how we understand value in the Progress Economy, where we, for example, distinguish between:

- potential value – how much progress could be made compared to what I am seeking

- emerged value – how much progress has been made compared to my expectations

- recognised value – how much of that emerged value is meaningful to a specific seeker on that specific attempt

But how do we measure progress?

By convention, we assume that no progress has been made until a progress attempt is initiated. Reaching the Seeker’s more desired state implies full progress has been achieved. These become the boundary markers: zero and maximum recognised value. Points in between can be tracked on a scale of progress. That becomes emerged value – but this only becomes meaningful when that progress is recognised by the Seeker. It’s a process not unlike revenue recognition in accounting.

In some domains, well-established scales already exist. Distance, for instance, can be measured in kilometres (or miles, or even Swedish mils, where 1 mil equals 10 km). In others, we need to introduce artificial progress scales, like the HSK grading system for learning Mandarin Chinese, where HSK 1 denotes basic competence and higher numbers denote increasing mastery.

An interesting consequence arises. Helping someone make progress should be a conversational process. Without dialogue, the Helper can’t fully understand the continuous Seeker’s judgements or criteria, nor can they intervene effectively to prevent negative evaluations or help course-correct.

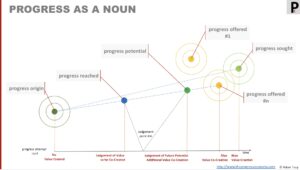

Progress as a Noun – naming waypoints and judgements of progress.

As we’ve just seen, it’s useful – and efficient – to name a number of specific progress states. Doing so sharpens our ability to describe the journey a seeker attempts and how propositions fit the story. It also lets us talk about the continuous progress comparisons a seeker makes along the way (which are central to understanding value).

The following progress states are particularly helpful in describing the journey:

- progress sought – the Seeker’s more desired state

- progress origin (seeker) – the Seeker’s current state

- progress origin (proposition) – the start state of a proposition

- progress offered – the state a proposition offers to help reach

Whereas the following three named states are phenomenological judgements of progress:

- progress reached – a judgement of how much progress has been made by a point in time

- progress expected – a judgement of how much progressed should have been made by a point in time

- progress potential – a judgement of how much progress can be made from a point in time

As we’ve seen, these judgements are used in comparisons leading to the notion of value.

By combining these named states with the understanding that each state comprises three elements – functional, non-functional, and contextual – we can move beyond conventional market segmentation approaches. This enables richer, more accurate segmentation than the typical focus on product features or demographic categories, opening the door to a deeper understanding of markets based on progress dynamics.

Progress as a State Transition – a useful alternative view

Progress can also be seen as a series of state transitions—a useful variant of seeing progress as a verb. This framing is especially helpful when examining value dynamics or mapping transformation journeys.

That’s our four ways of looking at progress. As a state helping us understand the details and nuances; as a noun naming important points on the journey; as a verb and a state helping us understand that progress journey and attempts.

Our view of progress happily provides a unified home for many business theories from over the decades.

Welcome home key business theories

Ever feel overwhelmed by the sheer volume of business theories claiming to unlock innovation, sales, and growth? You’re not alone. From frameworks to toolkits, the landscape is cluttered and fragmented. Progress-first thinking brings them home into a unified way of understanding. Here’s a few examples.

“Job to be done”

Progress-first thinking naturally aligns with the core of Jobs to Be Done (JTBD) theory – pioneered independently by Tony Ulwick and Clayton Christensen. At its heart, JTBD isn’t about products or services per se; it’s about the fulfilling specific tasks or jobs people are trying to make.

As Ulwick explains:

People want products and services that will help them get a job done better and/or more cheaply

What is jobs to be done,

And Christensen clarifies:

Successful innovations help consumers to solve problems – to make the progress they need to…

Know Your Customers’ “Jobs to Be Done”, HBR

Christensen defines a job in a very familiar way to us thinking progress-first:

…the progress that a person is trying to make in a particular circumstance

Christensen, C. M., Dillon, K., Hall, T., Duncan, D. S. (2016) ”Competing Against Luck: The Story of Innovation and Customer Choice” Harper Business; 1 edition

JTBD aligns directly with the combination of progress origin, progress sought, and progress as a verb elements of the Progress Economy. For example:

- progress origin: speak no Mandarin

- progress sought: speaking Mandarin at HSK level 3; to have had fun; can only do in evening

- progress as a verb: learning to speak Mandarin from no knowledge to HSK level 3; to have fun doing so; and to do so only in the evening

And the Progress Economy takes things further. It tells us:

- How the job might be done (through resource integrations)

- What might hinder the job – progress hurdles – foundational or related to the specific proposition

- How/Where someone can best help, and under what constraints

In this way, progress-first thinking doesn’t just support JTBD—it enhances and operationalises it, providing a robust foundation for innovation that matters and sales that convert.

Levitt’s Marketing Myopia

The classic trap described by Theodore Levitt in his 1960 Harvard Business Review article is as relevant today as ever:

“People don’t want a quarter-inch drill. They want a quarter-inch hole.”

Levitt’s warning was clear: companies that define themselves by what they produce rather than by the progress they help customers make are setting themselves up for loosing customers. They become product-centric when they should be progress-centric.

Progress-first thinking offers a remedy. Our focus is on the quarter-inch hole and the wide range of options on how that can be made.

Seen this way, Levitt’s insight isn’t just a warning—it’s a strategic invitation to reframe entire categories, to look beyond what is being sold and focus instead on what is truly being bought: progress.

Drucker’s ”Innovate or Die”

This is a challenge to progress propositions, who’s:

Seekers live in a dynamic world. They are constantly gaining new resources and raising their expectations of progress sought from the progress attempts they make – not just in your industry, but across all industries and markets they are in and observe.

- progress origin fall behind the seekers – leading to over resourcing, and potential seeker frustration at time/progress wasted

- progress offered fall behind progress sought – leading to lower offered vs sought comparison (a part of value judgements)

To stay attractive, progress helpers must adapt their propositions.

A direct succinct explanation of this is Drucker’s enduring insight:

Innovate or die

P. Drucker, via “Innovation on the fly”, HBR

Drucker saw innovation not as a luxury, but a lifeline:

“The business enterprise has two—and only two—basic functions: marketing and innovation. Marketing and innovation produce results; all the rest are costs.”

In a Progress Economy:

- Innovation = creating new or better ways to make progress

- Marketing = understanding what progress Seekers now want, and under what conditions, and where they currently are

That makes Drucker’s phrase a blunt but accurate summary of progress dynamics: If you fail to adapt your propositions to evolving progress sought, progress origin, and hurdles, you lose relevance, lose Seekers, and eventually, lose the game.

Disruptive innovation (The Innovator’s dilemma)

Disruptive innovation, as originally articulated by Clayton Christensen, is frequently misunderstood. A progress-firstperspective helps clarify the true mechanics—building directly on what we’ve just seen regarding “innovate or die.”

Christensen’s core insight:

“Disruption describes a process whereby a smaller company with fewer resources is able to successfully challenge established incumbent businesses… by targeting overlooked segments and delivering more appropriate functionality – frequently at a lower price.”

(Christensen, C. M., Raynor, M. E., & McDonald, R. (2015), HBR)

These overlooked – or left-behind – customers arise as a direct consequence of innovation dynamics: over time, Seekers evolve their progress sought, and Helpers feel compelled to keep pace by refining their propositions to remain relevant (or just catching up with Seeker’s initial expectations). But not all Seekers evolve in the same way, or at the same pace.

Chasing high-demand Seekers makes economic sense; they typically offer higher exchange potential. But in doing so, Helpers will over-serve less demanding Seekers – those whose progress sought is more modest or stable. For these customers, the incumbent proposition represents overkill. It may offer too much resource which often comes at too high an equitable exchange (for simplicity, think price).

This is where the disruptor enters.

Often leveraging new technologies or delivery models, the disruptor creates a progress proposition that is good enough for these underserved Seekers. It matches their more modest functional needs, aligns with their non-functional preferences, and fits their context better. It often comes with lower service-exchange demands.

Once adopted, the same evolutionary pressure kicks in: as these Seekers begin to evolve, the current disruptor’s proposition must evolve too. And as it does, it begins to be attractive to more demanding progress segments – eating into the incumbent’s Seeker base.

The incumbent finds itself trapped: it cannot afford to lose its high-value Seekers, yet struggles to match the disruptor’s evolving appeal downstream. This is Christensen’s Innovator’s Dilemma. If the disruptor captures enough of the incumbent’s base, disruption occurs.

But disruption is not a one-off event. The cycle resets. The disruptor of today, now chasing higher-value Seekers, risks overlooking tomorrow’s underserved. The terrain of progress keeps shifting. It would also be interesting to see if this dynamic occurs with progress origins.

Does a progress-first view offer help? Yes, segmenting on progress helps you understand the under-served/forgotten markets and determine if you strategically want to go there or not.

Blue Ocean Strategy

Blue Ocean Strategy, as articulated by W. Chan Kim and Renée Mauborgne, advocates for creating new, uncontested market space—what they call “blue oceans”—rather than competing in saturated markets (“red oceans”).

the simultaneous pursuit of differentiation and low cost to open up a new market space and create new demand. It is about creating and capturing uncontested market space, thereby making the competition irrelevant

https://www.blueoceanstrategy.com/what-is-blue-ocean-strategy/

The focus is on value innovation: making the competition irrelevant by offering leap-in-value for customers. Key tools in Blue Ocean Strategy are the Strategy canvas – listing market factors along the x-axis and their perceived level in the market on the y-axis. The innovative step is to identify which can be eliminated, raised or lowered to find the blue ocean. New market attributes can also be added in that search. That is referred to as the Four Actions Framework.

Progress-first thinking explains blue ocean strategy if we consider these market factors as various elements of progress sought. That is the x-axis of the strategy canvas lists out the progress offered by various propositions. We can then apply the four actions framework to see if there are blue oceans of propositions.

Agile

Agile, as a methodology, reflects the observation that the more desirable state sought may not be fully known by a Seeker (or changes as more experience of progress towards it is made). Originating in the software development world, we can now find “agile” tagged onto any business topic you can think of, like agile project management or agile business analysis (see Agile Alliance).

The relation to progress-first thinking lies in understanding progress sought, and that that can change over time, together with value recognition.

To wrap up our overview of progress; let’s see how it relates to value and innovation.

UPDATING AND SIMPLIFYING

Relation to value

When we free our minds from the deeply embedded concept that manufacturers embed value and we exchange that for cash, we find that:

- Reaching their progress sought creates maximum possible value for a seeker

- There is no value at their progress origin

Value, then, incrementally emerges as the seeker moves over time between their progress origin and progress sought. There is value-through-progress.

value-through-progress: a view of value creation that sees value as being increasingly created as progress is made. Though any value created may not be recognised (accounting term) until progress completes.

We say that value is a trailing indicator for progress. It’s not value we try and create, it is progress.

If a seeker engages a proposition, then progress is a joint endeavour. Seeker and helper co-create value. We often referred to this as value-in-use. Though the maximum value co-created with a proposition is likely to be different than progress sought.

Interestingly, emerged value is not meaningful to a seeker. They need to recognise it for it to become meaningful. Value recognition is a process similar to revenue recognition, that anyone with a finance background will be familiar with.

Although a seeker’s schedule for recognition may differ from the continuous emergence of value. For example, it could occur:

- periodically

- at the end of each progress making activity

- when reaching milestones

- only when reaching progress sought (or offered)

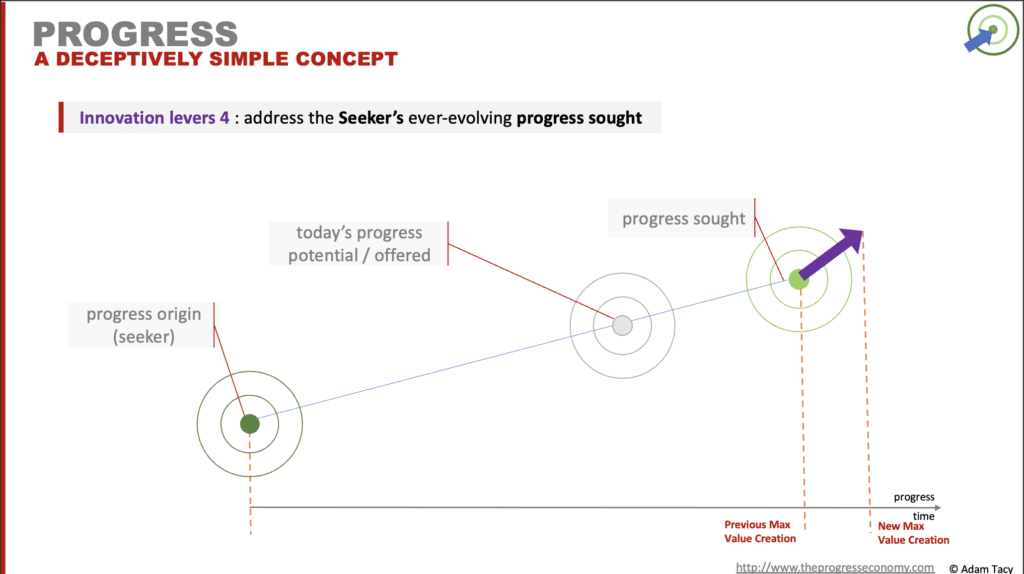

Relating to innovation

Innovation should enable a seeker to reach as close to their progress sought as possible. Since that is where maximum value has emerged. Failing that, innovation should enable the seeker to make the progress currently possible in a better way. Practically both these require reducing the lack of resource progress hurdle.

Seekers may attempt to improve their progress themselves. They may design and try different progress-making steps. Or utilise existing resources they have access to in novel ways. Perhaps they find new resources in their environment, or acquire them in seemingly unrelated progress attempts. They may even engage progress propositions in a novel manner.

Helpers, likewise, look to innovate their propositions. Aiming to help seekers reach further or make progress currently possible better. Or to close the gap between seekers’ and proposition’s assumed progress origin. They may additionally reduce the five additional progress hurdles that progress propositions introduce.

Finally, we observe that innovation is continuously required. It is driven by the fact that progress sought continuously evolves. It is shaped by seekers’ experiences in attempting progress in various aspects of life, including in other industries, markets, and global perspectives. As well as their observations of others attempting progress. Similarly seekers’ progress origins can shift over time.

Although innovating to chase the evolving progress sought of your most demanding seekers may expose you to be disrupted. That’s part of Christensens “Innovator’s dilemma“.

Let’s progress together through discussion…