The value model that built industries is now holding us back. Uncover the details, and the blind spots that are capping your sales, stalling your innovation, and limiting your growth in today’s economy.

What we’re thinking

Our traditional view of value – called value-in-exchange – frames value as something:

- manufacturers progressively embed in goods through the supply chain

- exchanged, usually for cash, at a point of sale

- end customers then ‘use up’ or destroy that value.

Innovation’s focus under this model is to create or add more value. Sales is about getting greatest exchange of value. Yet, as we know, value is very difficult to define.

To its credit, this model has been wildly successful for centuries, and it’s no wonder we cling to it.

However, the exchange-point focus and goods-dominant basis brings growth-limiting blindspots, including:

- Prioritising consistency over customisation

- Chasing the next transaction instead of supporting customers post-exchange

- Valuing new exchanges over circular thinking

- Elevating goods over services

- Falling into marketing myopia

- Favouring simple exchange over more innovative business models

- Assuming providers define value

With growth stagnating across many industries and economies, it’s time to question whether this model is still fit for purpose. Evolving toward value-in-use – or better yet, value-through-progress – opens up new avenues for sales, innovation and growth.

value in exchange key concepts: Embedding and Exchanging value

Let’s review our traditional model of value – value-in-exchange – to understand both its long-standing success and its emerging limitations.

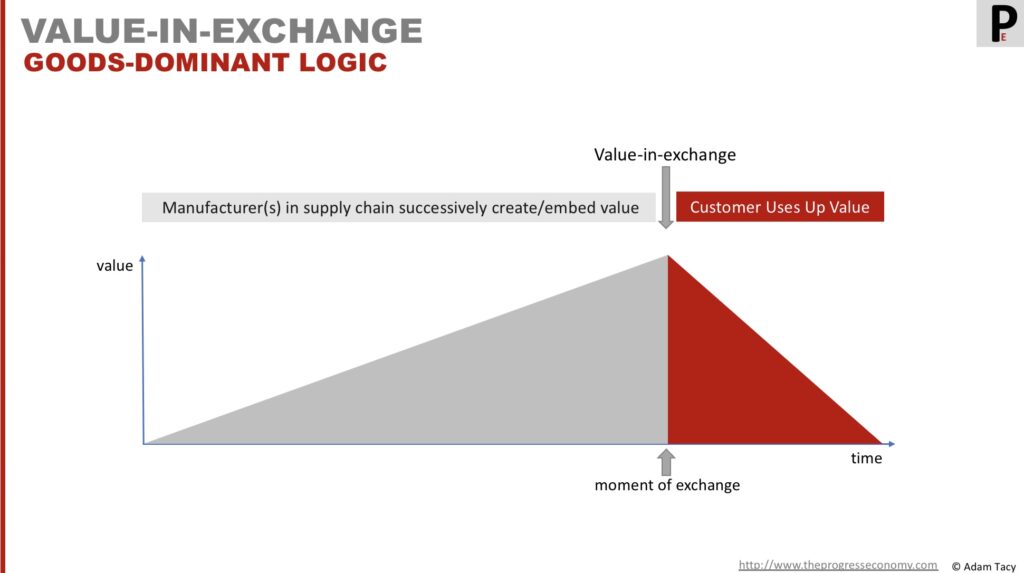

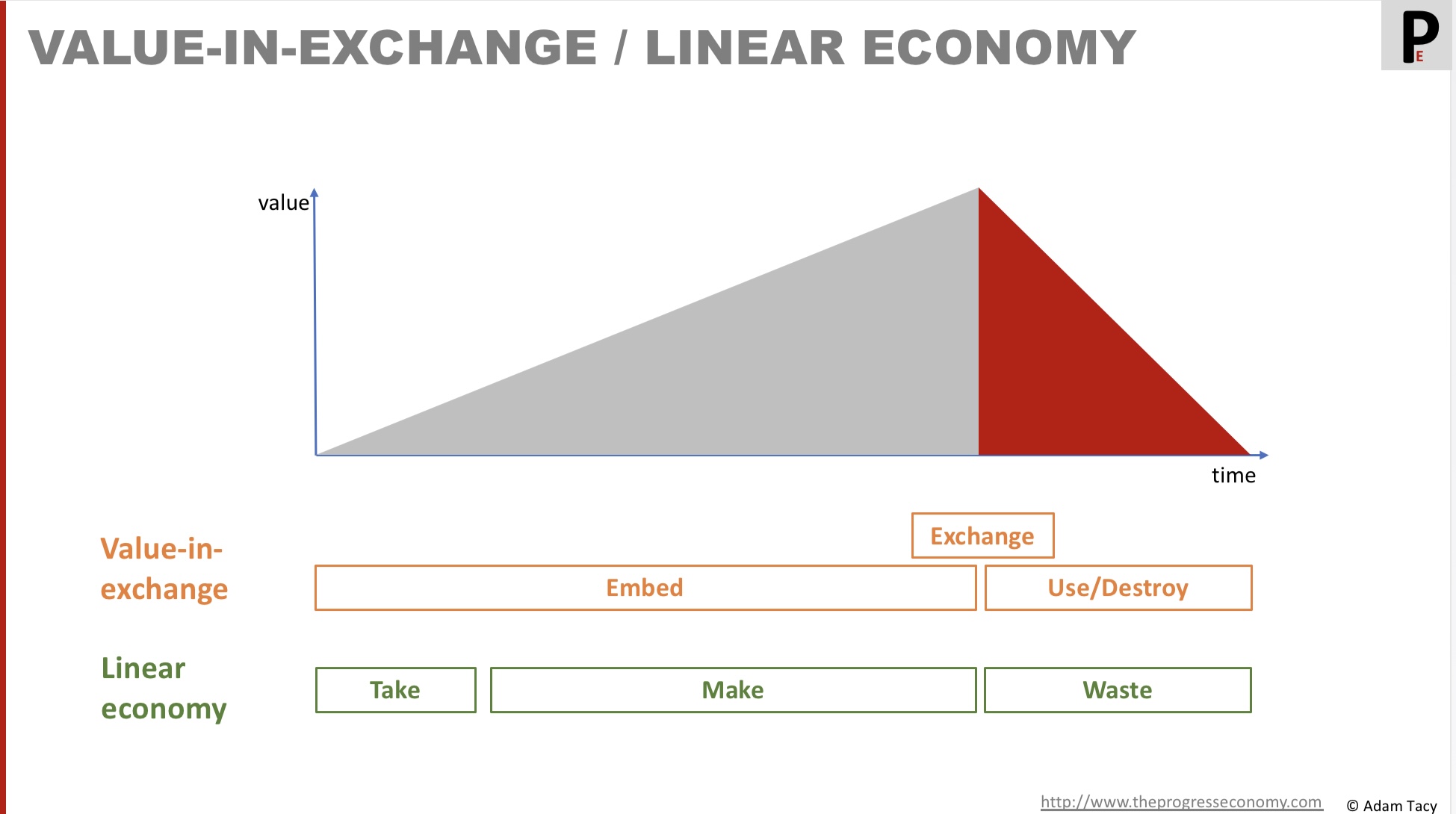

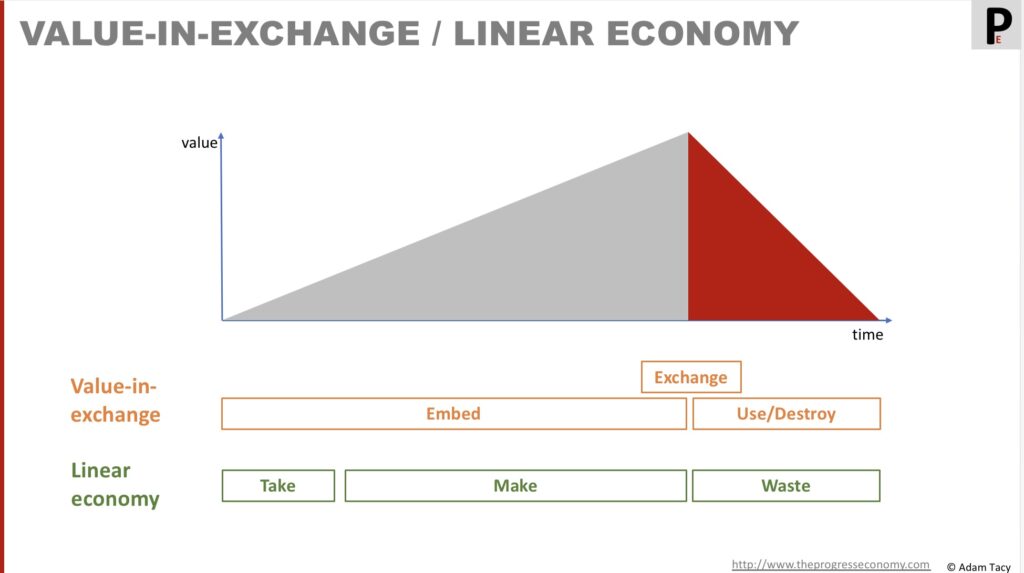

value-in-exchange – value is progressively added throughout the supply chain by manufacturers, exchanged at point of sale, and subsequently used-up/destroyed by end customer

Value-in-exchange sees value as something embedded in goods or services by manufacturers. Value is realised at the point of sale, exchanged for cash. Once the customer takes ownership, they proceed to use up or destroy that value.

This model is deeply familiar. Manufacturers create products, signal value through price, and customers buy, own, and consume that embedded value. It’s a system where value is measured in price—what McKinsey summarised as:

A product’s value to customers is, simply, the greatest amount of money they would pay for it.

Golub, H., and Henry, J. (1981) “Market strategy and the price-value model” via “Delivering value to customers”, McKinsey (2000)

We see this everywhere: buying food, paying for transport, subscribing to media. It’s central to what Vargo and Lusch describe as goods-dominant logic, contrasted with their service-dominant logic that emphasises value-in-use.

The value-in-exchange model has undeniably driven economic success, yet its focus on the transaction blinds us to significant growth opportunities. It also shapes our approach to innovation. We tend to think of innovation as adding more embedded value. On the surface, this seems right – but we now face an innovation problem.

Let’s look at how we define, create, and measure value. This will lead us to the blind spots and challenges we’ve mentioned. And to why innovation in value-in-exchange is prone to disappoint 94% of executives.

defining value: the greatest amount of money a customer would pay for a product

Take a moment—how do you instinctively define value?

Most of us would reflect our everyday experience: exchanging hard-earned cash for products and services – a car, fuel, coffee, books, a flight, eating in a restaurant, etc. Leading us to McKinsey’s view that value equates to price.

A product’s value to customers is, simply, the greatest amount of money they would pay for it.

Golub, H., and Henry, J. (1981) “Market strategy and the price-value model” via “Delivering value to customers”, McKinsey (2000)

Measuring value: Price

Value is measured on the output – the goods or services. Price is the proxy, signalling the value embedded in a product.

Manufacturers, and service providers, determine value and signal it via price. The customer’s incentive to buy is seen as the gap between value and price. Anderson & Narus (“Business Marketing: Understand What Customers Value”, HBR, 1998) encapsulate this as the equation:

Academic literature provides variations on this equation, typically balancing benefits and costs:

Woodside, A.G., Golfetto, F., Gibbert, M (2008) “Customer value: theory, research and practice”; Advances in Business Marketing and Purchasing 14:3-25

Porter’s classic strategies are rooted here ((Porter (2004) “The Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors“):

- Differentiation: Embed more value and maximise price per exchange.

- Cost leadership: Minimise price to maximise transaction volume.

It’s also not uncommon for manufacturers or service providers to provide a base product and offer additional features at extra cost. Low-cost airlines provide a notable example, with a base fee for a seat and additional fees for baggage, printed tickets, assigned seats, and so forth. Each option taken is an additional exchange of value – how valuable are they to you.

creating value: embedding

The traditional value-in-exchange model sees manufacturers embedding value as products move along the supply chain.

This is easy to visualise:

Raw materials → (sale →) Components → (sale →) Products → Sale → Customer uses/destroys the value.

Take a car. It holds more value than its parts, which hold more value than the raw materials. Each step embeds more value. Even services get squeezed into this model: providers design services, deliver them, and exchange those units of service for cash—just as if they were selling goods.

In this view:

- Value is a property of goods and services.

- Value increases through the supply chain.

- Value is exchanged at transaction points.

Once the customer buys, the provider’s job is done. All attention shifts to chasing the next transaction.

But what happens after the sale? The customer destroys the value they purchased.

destroying value: Using Up or destroying

Once the sale to the end customer occurs, we see them begin to consume/use-up or destroy that embedded value.

Drive a new car off the lot – it instantly loses a large amount of its perceived value. Then, over time, you further diminish its value through use. Eat a chocolate bar and you instantly destroy the embedded value. In services, this is often called consumption – using up the value as it’s delivered, which is often seen as a single moment in time.

The model’s benefits: previous wild success

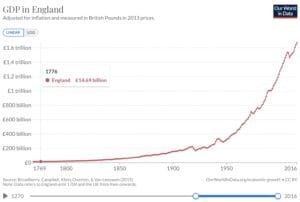

Our value-in-exchange model is the foundation of neoclassical economics. Adam Smith captured this in his 1776 classic, The Wealth of Nations, arguing that a nation’s wealth is linked to maximising the amount of gold and silver received in exchange for the goods and services it supplies.

(It’s also worth noting that Adam Smith originally introduced both value-in-exchange and value-in-use concepts before ultimately choosing to frame his worldview through value-in-exchange (see Vargo, Maglio and Akka (2008) “On value and value co-creation: A service systems and service logic perspective”; European Management Journal; vol 26).)

There is no doubt this model has been wildly successful. Just look at the growth since Smith’s time. Using Gross Domestic Product (GDP) for England as a proxy, economic growth soared from £14.6 billion to £1.67 trillion by 2016, adjusted for 2013 prices (source).

This success is deeply tied to the model’s intense focus on the point of exchange. That focus shaped manufacturer behaviour – driving them to maximise either the size of each exchange or the number of exchanges. It’s this relentless pursuit that has fuelled consistent product improvement year after year.

Yet, to fully understand where this model may now be limiting us, it’s essential to explore its deeper implications and blind spots.

Implications of value-in-exchange

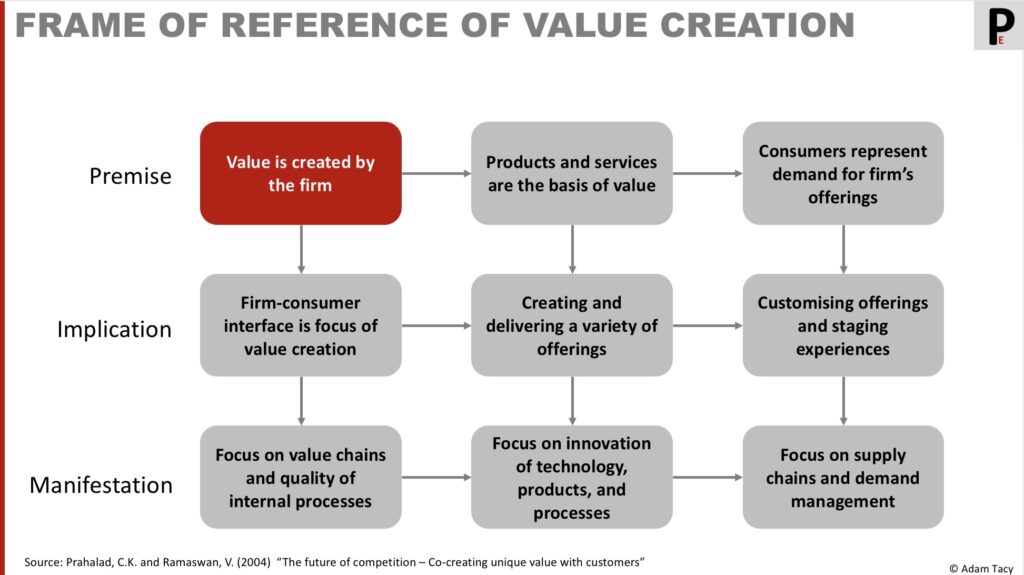

Prahalad and Ramaswamy, in their 2004 book The future of competition – Co-creating unique value with customers, neatly summarise the strategic implications of the value-in-exchange model.

Their key diagram lays out the premises, implications, and manifestations of value-in-exchange. Strikingly, the customer’s perspective is largely absent. They show the model is heavily inward-facing, driven by firm-centric priorities.

Prahalad and Ramaswamy start with the foundational premise that value is created by the firm. From there, their logic unfolds both horizontally and vertically.

For example:

- Horizontally, if you accept that value is created by the firm, you naturally align with the idea that products and services are the core units of value. This leads to the assumption that consumers merely represent demand for the firm’s offerings.

- Vertically, starting with the same premise leads to the belief that the point of exchange is the focus of value creation—what they call the firm-consumer interface. This flows directly into a focus on value chains and internal process quality as the core levers of improvement.

This helps explain why the customer often becomes an afterthought in the traditional value model. Even though the right side of their framework briefly references customisation and staged experiences, the overriding focus on the point of exchange systematically leads us to the blind spots of the model.

The model’s constraints: blind spots on future growth

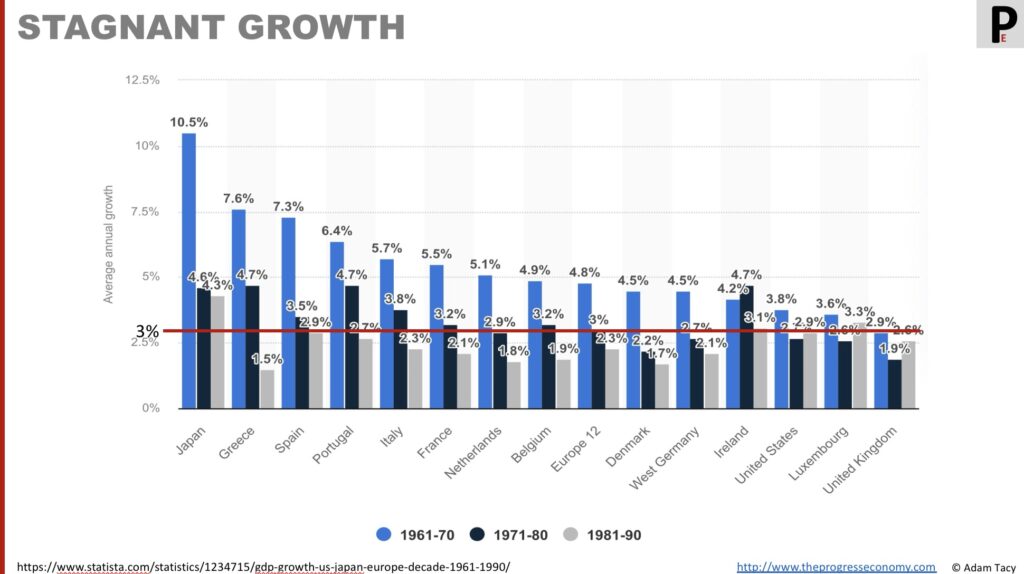

The era of strong growth driven by the value-in-exchange model may be running out of road. Growth is stagnating across many advanced economies, and the traditional model seems increasingly unable to unlock new sources of value.

Between 1969 and 1990, GDP growth began decelerating in many countries, hinting at the model’s limitations.

The IMF’s Kristalina Georgieva warns of the “Tepid Twenties,” forecasting a decade of sluggish, below-average growth unless we correct course.

Our medium-term outlook for global growth remains well below its historical average. It is just, just slightly above 3%. Without a course correction, we are indeed heading for ‘the Tepid Twenties’ — a sluggish and disappointing decade

Kristalina Georgieva, International Monetary Fund chief, April 2024

Why is growth stagnating? I believe the inherent blind spots of the value-in-exchange model are a significant factor. These blind spots restrict where and how we pursue growth, we:

- tend to ignore opportunities before, after, and across the point of exchange.

- prioritise consistency over customisation.

- chase the next transaction instead of extending or recovering value.

- favour volume of exchanges over circular economy principles.

- default to goods over services.

- suffer from marketing myopia.

- simplify exchanges instead of exploring new business models.

- see manufacturers, not customers, judging value.

Let’s explore these blind spots.

Consistency Over Customisation – Missing Value Before Exchange

The focus on maximising exchanges drives businesses to favour consistent, standardised products that require minimal customer involvement. Mass production makes this economically attractive: it reduces costs and delivers repeatable value.

But this obsession with consistency has consequences, we:

- miss opportunities to create additional value before the exchange

- often restrict customisation options – even when customers would value them

Consider how car manufacturers limit personalisation to a narrow range of paint colours and option packs. The logic is efficiency, but it leaves latent customer value untapped.

Vargo and Lusch, in The Four Service Marketing Myths, argue that we should reframe inconsistency (one of the 5I’s of service) as customisation. It is a positive feature that enables customer co-creation. Yet, goods-dominant logic pushes us towards uniformity.

This bias also steers us toward goods over services. Even when we offer services, we try to standardise them to behave like goods.

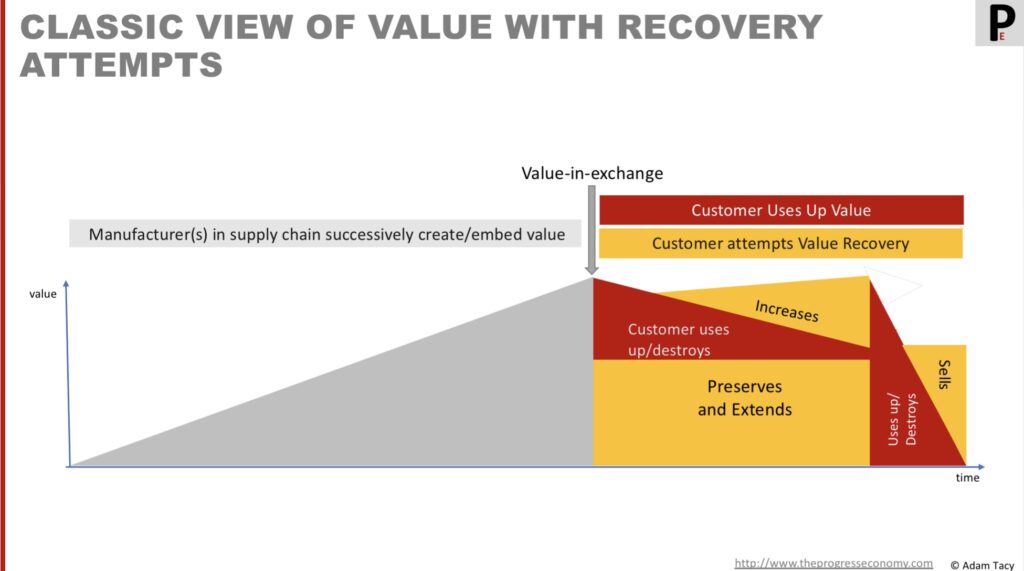

Chasing the Next Exchange: Missing Value After Exchange

Value-in-exchange thinking often ignores what happens after the point of exchange.

Once a customer buys a product, businesses typically turn their attention to securing the next sale. Worse, the model rewards quick consumption because it leads to more exchanges.

Take buying a car. The moment you drive off the lot, the car’s exchange value plummets. Over time, using the car consumes its remaining value until it’s scrapped. But that’s not the end of the story.

Servicing, repairing, modifying, and reselling can all recover or extend value. These activities matter to customers but often sit outside the manufacturer’s value model – and thus outside their strategic interest.

Osterwalder and Pigneur highlighted this gap in Modelling value propositions in eBusiness, noting that value consumption, renewal, and transfer are typically overlooked.

When businesses focus solely on the point of exchange, they leave valuable opportunities – repairing, recycling, refurbishing, reselling – for others to capture. Ignoring post-exchange value also stalls progress toward a circular economy.

Favouring More Exchanges Over Circular Economy: Missing Value Across Exchange

The value-in-exchange model aligns with a linear, “take-make-waste” economy. It encourages manufacturers to design products that degrade quickly, incentivising more exchanges.

The Ellen MacArthur Foundation identified this as a core challenge for circularity: transitioning to a circular economy requires us to revisit the very notion of value creation.

One of the biggest challenges… to transition from linear to circular is that it requires… revisiting the very notion of value creation.

Ellen MacArthur Foundation (2023), From ambition to action: an adaptive strategy for circular design

The 2024 Circularity Gap Report paints a stark picture. The share of secondary materials in the global economy fell from 9.1% in 2018 to 7.2% in 2023 – a 21% decline in just five years. This drop signals a systemic failure to design for recovery, recycling, and reuse.

The share of secondary materials consumed by the global economy has decreased from 9.1% in 2018 to 7.2% in 2023—a 21% drop over the course of five years.

Circle Economy Foundation (2023) “The Circularity Gap Report 2024”

Value-in-exchange offers no inherent incentive to make products repairable or recyclable. Why would a manufacturer invest in extending product life if that might reduce the number of future exchanges?

Regulation sometimes forces exceptions. For instance, Sweden mandates a deposit scheme for plastic bottles. In 2022, Swedes recycled 86.7% of bottles and 87.8% of cans for recycling. But these are external corrections, not natural outcomes of the value-in-exchange model.

Goods Over Services: Limiting the Solution Space

The traditional value model favours goods because they support the exchange-centric mindset:

- Goods separate manufacturing from use.

- Tangibility allows inventory creation.

- Goods “embed” value, which customers later consume.

Even when businesses offer services, they often try to standardise them to behave like goods. The IHIP framework (intangibility, heterogeneity, inseparability, perishability – Zeithmal, Parasuraman and Berr’s “Problems and Strategies in Service Marketing) reinforces this goods-vs-services dichotomy, positioning services as inferior.

But this thinking is becoming obsolete. Today’s goods are increasingly intangible – digital music, videos, eBooks – and no longer require inventories. Even tangible goods now rely on just-in-time production with minimal stockholding. The rise of 3D printing could push this trend further, creating products on demand.

Vargo and Lusch (The Four Service Marketing Myths, 2004, Journal of Service Research 6(4):324) argue that we should embrace the positive attributes of services:

- Intangibility: Unless tangibility has clear marketing advantages, it should be minimised.

- Inconsistency: Customisation should replace standardisation as the normative goal.

- Inseparability: We should maximise customer involvement in value creation.

- Inventory: The goal should be to reduce inventory and maximise service flow.

Their challenge is clear: we must stop privileging goods.

Marketing Myopia

The goods-vs-services mindset feeds a deeper problem: Leviott’s Marketing Myopia.

As Levitt warned, we risk defining customer needs too narrowly – viewing them only through the lens of our current products. The value-in-exchange model entrenches this by making it difficult to abandon existing high-volume solutions in favour of something fundamentally different.

The classic example is the music industry’s slow shift from selling physical products to embracing streaming—a clear case of goods-dominant logic blinding firms to emerging customer value.

Simple Exchange Over Business Model Innovation

The traditional model favours straightforward, bi-party, one-off exchanges. Alternative models – subscriptions, subsidised pricing, platform services – often feel counterintuitive in a value-in-exchange mindset:

- Subscriptions break large exchanges into smaller, recurring ones.

- Subsidised models increase the number of actors and lower per-transaction prices.

- Platform as a Service charges for usage, reducing the perceived size of each exchange.

These models succeed not because they simplify the exchange, but because they align more closely with how customers experience and create value.

Yet many firms hesitate to adopt them because they don’t fit comfortably within the value-in-exchange framework.

Manufacturer as Judge of Value

Finally, the value-in-exchange model places the manufacturer in the position of value arbiter. The price set by the provider is treated as a proxy for value.

We often claim that customers ultimately determine value through their purchasing decisions. But in practice, the initial value judgement – what’s offered, how it’s priced – is made and driven by the manufacturer/producer.

The introduction of self-service checkouts in supermarkets is a vivid example. Retailers prioritised cost reduction and operational efficiency, justifying the rollout by presuming these changes were valuable to customers. But the backlash tells a different story.

- Theft rates increased.

- Anti-theft measures alienated customers.

- Some retailers are now scaling back self-checkouts.

The failure here stems from assuming producer-defined value aligns with customer-defined value. That’s a dangerous misstep, especially as we saw earlier that B2C companies struggle to define what value is.

innovation through value-in-exchange lens

Innovation drives growth by increasing a customer’s incentive to buy ((). It therefore aims to add/create more embedded value, reduce price, or do both. That is:

Some companies also innovate by unbundling their products, creating options that feel customised while optimising pricing.

The chair of ISO’s committee developing a standard for innovation reflects this focus, though expands to it being not just financial.:

Innovation is about creating something new that adds value; this can be a product, a service, a business model or an organization. And the value that is added is not necessarily financial, it can also be social or environmental, for example

Alice de Casanove, Chair of the ISO technical committee responsible for ISO 56000 (2020) – Innovation Management – Fundamentals and Vocabulary

Types of innovation: Incremental over radical

The value-in-exchange model often nudges companies toward incremental innovation. When companies focus on improving existing exchange flows, they prefer safer, smaller improvements.

Radical innovations, on the other hand, reshape or create entirely new markets. These often require new exchange flows—flows that incumbents hesitate to pursue because they risk disrupting their current revenue streams. Consider Kodak. The company invented the digital camera in 1975, developed digital sharing technologies, and even acquired a photo-sharing site in 2001. But Kodak couldn’t let go of the highly profitable film-based exchange flow. That resistance ultimately led to its bankruptcy. See Anthony, S. D. (2016) “Kodak’s Downfall Wasn’t About Technology”, HBR.

Blockbuster faced a similar trap. Despite developing an online strategy that could have countered Netflix, activist investors and new leadership forced a retreat to the old model of late fees (see ex-CEO John Antioco story). The company clung to its legacy flow – and lost.

Pharmaceutical and large computing companies often navigate these transitions more effectively. Their R&D-driven models anticipate that new products will cannibalise old ones. But even here, R&D alone is not enough. Organisations also need the courage and operational capability to commercialise disruptive innovations. Xerox is a well-known example of a company that invented breakthrough technologies but failed to exploit them.

New entrants hold an advantage. Without existing exchange flows to protect, they can pursue radical innovation more aggressively. But they face the opposite challenge: building and scaling new flows from scratch.

A prime example of exchange-based business model innovation is the razor-and-blade (or bait-and-hook) business model. This model thrives on the necessity for ongoing exchanges for product components to sustain their functionality. Classic instances are razor blades from Gillette, printer ink cartridges from Canon, and coffee capsules from Nespresso.

Editing below here

Key take aways

- Value-in-exchange is how we traditionally observe value in our world working. Cash is king, and we’ll readily exchange it for products we see as holding value (that has been progressively added by manufacturers in a supply chain). It has been a wildly successful model, driving impressive growth over the past few centuries.

- We measure value through a customer’s incentive to buy

- However, it has several built in blind spots due to the heavy focus on a point of exchange. Those limits our view of value creation before, after and across the exchange. We leave customisation, value recovery and the circular economy behind.

- Value itself is difficult to define. At best we find it is “gains from satisfying needs and expectations”. More often it is just the “amount someone is willing to pay”.

- Innovation is about adding (embedded) value; increasing the customers incentive to buy:

- We organise our firms around making value exchanges, looking to maximise the size, or number, of exchange. This means our innovation ambitions tend towards incremental – small changes – rather than radical – market/industry changing. Why risk established exchange flows?

- Our innovation initiatives are often misaligned with corporate innovation ambitions; or with value as seen by the organisation.

Let’s progress together through discussion…