What we’re thinking

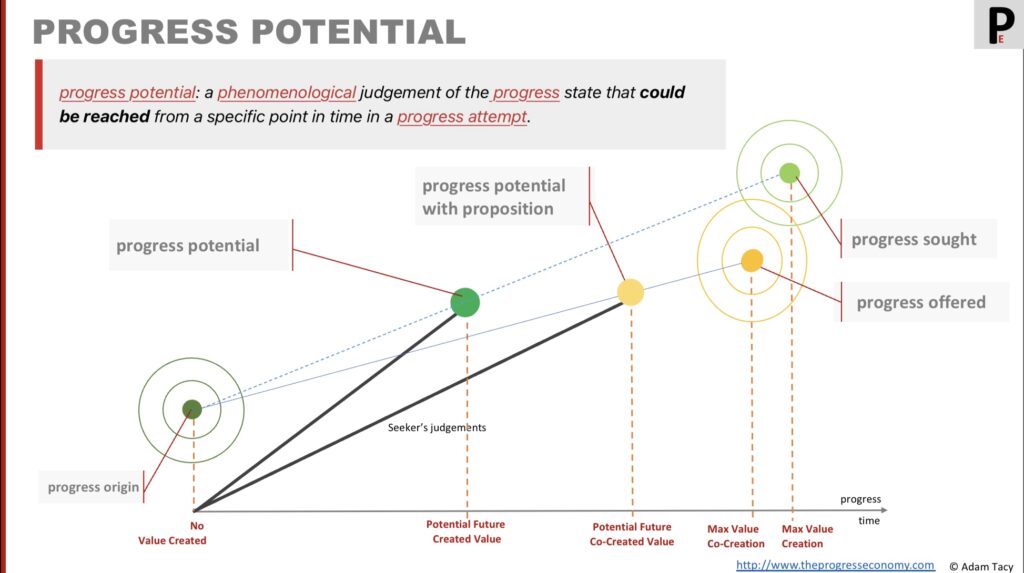

Progress potential is the progress state that an actor phenomenologically judges, at particular moment in time, could be reached in a progress attempt.

It is regularly judged by progress seekers as part of their decision process to start and continue progress attempts, alone or with propositions.

Progress Potential – judged continuously by a seeker it reflects their view of progress that can be made from points in time on a progress attempt; as value emerges from progress, it is a prediction of future value Share on XProgress helpers predict it for their propositions, where it becomes known as progress offered. And, in some cases, helpers judge progress potential with a particular seeker during attempts, influencing whether they withdraw access to their resources.

Since value emerges through progress, progress potential is a prediction of future value. Innovation should enhance seekers’ judgments of progress potential.

Progress potential

Progress potential is the judgment, at a specific moment, of the progress state that could be reached in a progress attempt. It is one of the named states in the progress economy, forming a pair of phenomenological judgments alongside progress reached.

progress potential: the phenomenological judgement, at a point in time, of the progress state that could be reached in a progress attempt.

Both the seeker and helper have perspectives on progress potential.

the seeker’s perspective

We see the seeker as primary adjudicator of progress potential. They do so at the start of, and regularly during, a progress attempt,

When starting an attempt seekers are judging how close to their progress sought they feel they will reach. If too far, they look for progress propositions to help. These propositions should make the seeker feel they get close enough to their progress sought.

However, a propositions end point is progress offered. So a seeker judges not only is progress offered near enough their progress sought but also the progress potential of the proposition.

a helper’s perspective

While the primary actor n the progress economy primarily is the seeker, helpers also assess progress potential. Doing so in two ways.

During the creation of a proposition, helpers determine the progress state they believe their proposition can potentially help reach. This view of progress potential we better know as “progress offered“.

Additionally, helpers may assess the progress potential that specific seekers or groups of seekers might achieve with their proposition. Based on this judgment, a helper may decide whether or not to offer access to their supplementary resources.

For instance, a provider of advanced language course may assess progress potential of a beginner seeker and decline to accept them in their coyrse. Or luxury car dealership may decide to assess the wealth of potential customers (a measure of equitable exchange capability) before fully engaging with them, recognising that not everyone will be able to participate in an equitable exchange with them.

Measuring progress potential

While the idea of measuring progress potential is tempting, it can be complex due to the multifaceted nature of progress (functional, non-functional, and contextual elements). As well as the phenomenological nature of these judgements.

Nevertheless, it’s in our nature to measure. And we’ll talk about innovation as increasing perceptions of progress potential. Some progress can be directly measured – how far can we reach on a 100km journey, for example. Other progress is more abstract and requires us to define artificial scales.

For instance, consider the following examples:

- Binary Pass/Fail: For instance for functional progress sought: “becoming fluent in Mandarin Chinese”

- Standardised scales: standardised scales offer clear and objective assessments. We can use the number of deaths per year as a standardised scale of how safe something is.

- Subjective Assessments: measuring subjective factors like “feeling safet” can be more challenging. We may resort to asking individuals to rate their feelings between 1 to 10 to capture their personal perceptions.

- Complex Scoring Mechanisms: seekers may develop intricate scoring mechanisms to assess progress potential; such as B2B bidding processes. These mechanisms help evaluate and compare proposals based on predefined criteria.

Helpers often present their measurement of progress potential with their proposition, which as we’ve mentioned is really progress offered, from a sales perspective. For instance “9 out of 10 dentists recommend our toothpaste for freshest results”.

Relating to value

In the progress economy, we view value as emerging through progress. We therefore interpret judgments of progress potential as forecasts of future value (co-) creation.

The closer a seeker judges their progress potential is to their progress sought, the greater the potential for realising maximum value.

Relating to innovation

Increasing a seeker’s judgement of progress potential towards their progress sought is a key aim of innovation.

Let’s progress together through discussion…