What we’re thinking

Should you pay less is supermarkets when using a self-service checkout? After all, you are putting in more effort compared to using manned checkout. Is making your friend a meal a fair exchange for them helping you move house?

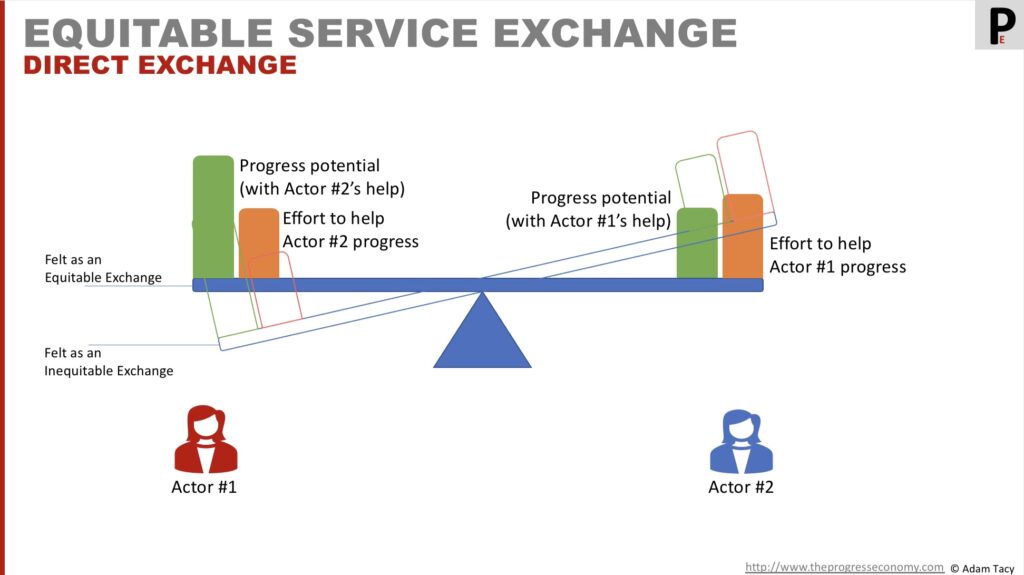

Service exchange does not need to be equal; it just needs both parties to feel it is equitable.

That is to say each party is comfortable the effort they themselves put in to help the other party progress is reflected in their progress potential when engaging the other’s help.

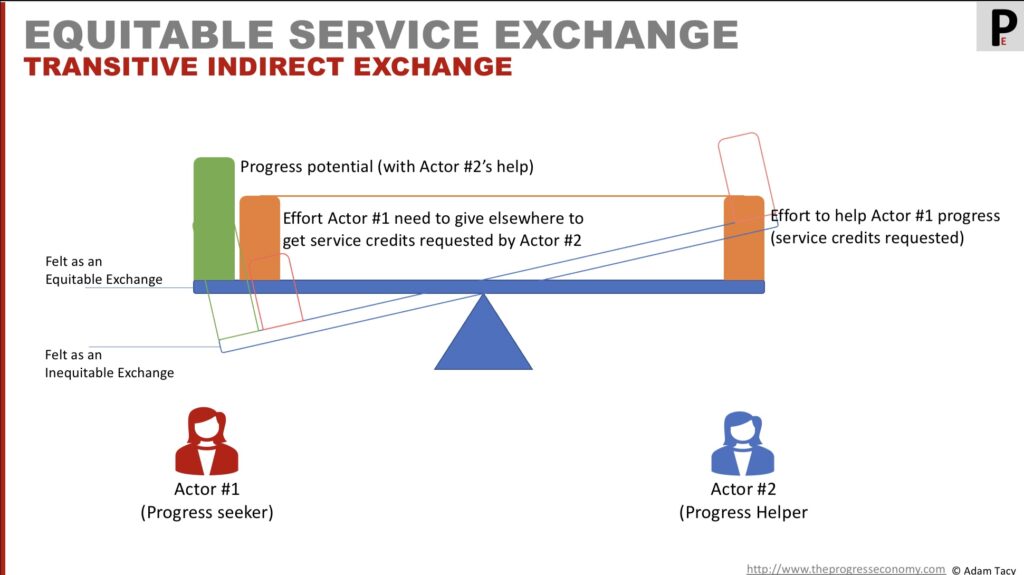

In the case of transitive indirect exchange the effort perspective evolves. Now it get interpreted by the progress seeker as the effort they needs to give (or have given) elsewhere in order to obtain the service credit(s) requested by the helper.

The more one party feels the exchange is inequitable, the higher the equitable exchange progress hurdle.

Interestingly, the concept of price (as effort, not value) and business model innovation (reducing seeker’s effort in exchange) emerge from this perspective.

Equitable service exchange

editing below here

In a simplistic world of service as the basis of exchange, every service would be equal, whatever that means. The implication being that service exchange is straightforward. I make you a cup of tea, you service my car, and we’re even.

Except that feels somewhat unfair and unrealistic. Although that type of exchange might happen.

https://drexel.edu/news/archive/2024/January/Does-Self-Checkout-Impact-Grocery-Store-Loyalty

What’s going on? Well, it’s all about the concept of equitable service exchange. Any exchange is equitable if parties agree that once complete they have made the progress they expected with the help of the other party, for the effort they expected to have to give helping the other party make progress.

equitable service exchange: an exchange of service, where

It does not require the service exchanged to be equal in terms of effort or progress made. In fact, that could be impossible to quantify – in our example above, how do we equate quenching thirst with helping service a car?

The further apart the actors are on agreement of equitability, the larger the equitable service progress hurdle is.

Let’s explore this concept by first seeing how it works for direct service exchange and how that perspective evolves for indirect exchange.

Equitable service exchange – a direct exchange perspective

How can swapping helping to quench thirst through a cup of tea be equitable to jumping under a car and replacing filters, plugs and a range of fluids? After all, the magnitudes of progress and effort involved are vastly different.

Quite simply you and I, as the two actors involved, can agree it is equitable.

This is something actors can do relatively easily in a direct exchange. In such a case, each actor weighs up the progress they are able to make from the other’s help (progress potential) with the effort they need to give to help the other actor progress.

For me, I have the huge effort of boiling a kettle, choosing the tea, brewing it, adding milk and sugar whilst you’re thirsty working on my car. You, on the other hand have the tools and knowledge to help service my car that needs doing to keep me being able to travel.

We agreed the other day that you wouldn’t mind helping in return for a good cup of tea. I thought it was a great idea. So here we are, exchanging service and both happy with the exchange – it’s not equal but we agree it’s equitable.

If we hadn’t agreed it was an equitable exchange we may have tried to find a better one (perhaps 2 cups of tea?). And as the exchange takes place we’re re-evaluating it. Maybe my cup of tea is weak, grey, and like dishwater. Or you’re less of a mechanic than you mentioned; or my car is in worse state than thought. Either way we might have value co-destruction and/or a growing feeling of inequity in the exchange (progress reached being less than progress offered).

As we saw though when exploring service exchange, direct exchange is usually masked by indirect exchange. Does that bring any changes?

Equitable service exchange – a transitive exchange perspective

What happens when we look at transitive indirect service exchange? Where two actors are not exchanging service, rather one actor is exchanging a service for service credit(s) they could exchange for service from a different progress helper.

Now we find that the progress seeker sees the effort they have to give in service must match the effort of the progress helper. Since they need to get (or have already got) the service credits requested. And they can only get those by performing service exchange with others.

Service credits are value-less; we see from this they represent some measurement of effort. How much effort do I need to spend, as a progress seeker, giving service in order to get a service I want.

Implications

Price

perhaps best to talk about cost first. What is the cost of providing a proposition? Its all the effort required to run the helper (marketing, execution, innovation + the support functions) plus any effort of other actors in the ecosystem

price is effort * frequency

Explain self-service/enabling and relieving in terms of effort exchange

Business model innovation

Can you reduce Equitable service exchange requested? ESE = service from seeker + service from elsewhere

and that elsewhere could be ad-based, or otherwise supported.

helper effort could be all at once or spread over periods (subscription models)

Let’s progress together through discussion…