What we’re thinking

We’re eager to make progress…but what if we’re lacking the resources we need to do so?! Perhaps we lack the skills, knowledge, tools, maybe strength, or time, or…

We’ve hit the fundamental progress hurdle of the progress economy!!

progress hurdles – hinder progress, reducing value creation…let’s innovate them away Share on XLuckily, progress propositions offer supplementary resources that aim to lower this hurdle. But, they might not fully, or might introduce new lack of resource. And propositions give rise to five additional progress hurdles:

Higher hurdles imply lower judgements of progress potential, and therefore reduced value.

Though we call these hurdles rather than barriers as some seekers may still attempt (and succeed) even if they feel the barriers are high.

Naturally, reducing these hurdles is a rich zone for innovation.

Progress hurdles

We attempt to make progress through a series of resource integrations. Where each successful integration moves a seeker closer to their more desired state (progress sought).

But when a seeker feels they lack the necessary resources to make progress there is an issue. This is an example of what we call a progress hurdle:

progress hurdle – a factor that, if felt uniquely and phenomenologically by a progress seeker as too high, may lead them to decide not to start or to abandon a progress attempt

We call it a hurdle rather than barrier since it doesn’t necessarily block progress. Some seekers may see a hurdle yet decide to attempt to progress anyway. And some of those succeed.

And this “lack of resource” progress hurdle is the fundamental hurdle in the progress economy. It opens the door to progress propositions. However, the existence of propositions gives rise to five additional hurdles.

Before we introduce these hurdles, let’s explore how we can visualise them.

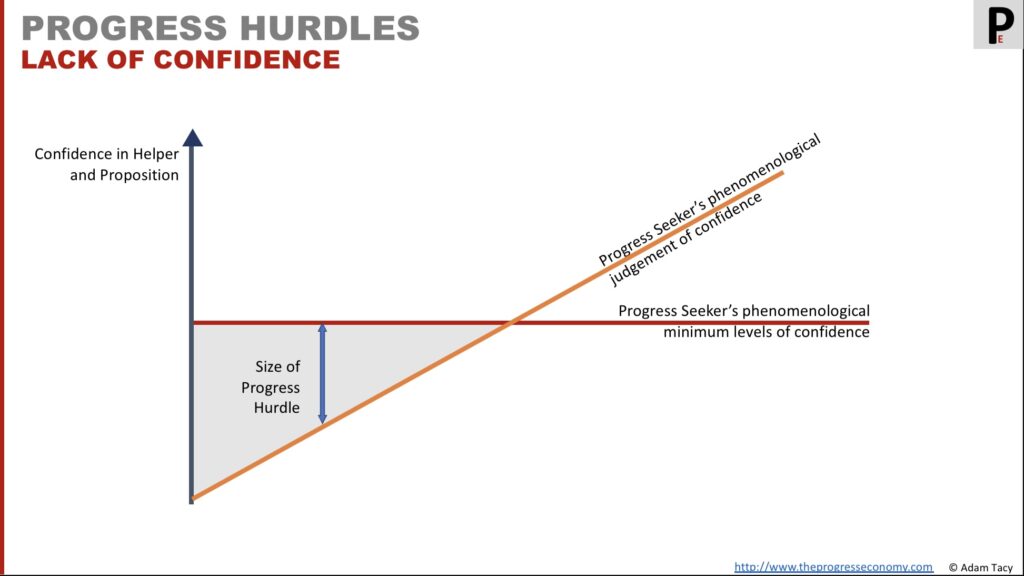

Visualising hurdles

Here’s an example of how we can visualise progress hurdles.

We see four key components in the diagram:

- The aspect under consideration as the vertical (think amount of resource, level of confidence etc)

- Horizontally is the hurdle itself – what the seeker judges as the minimum level of aspect under consideration needed to start a progress attempt

- Diagonally is the seeker’s judgement of the aspect they currently have

- Shaded area is where the seeker feels they are not able to get over the hurdle

Judgements are always unique and phenomenological to a progress seeker. And can also be different between the same progress attempt at different times/circumstances.

Let’s look at a brief summary of the lack of resource progress hurdle.

Lack of resources

In the progress economy, the lack of resource hurdle is the fundamental progress hurdle. Since progress is made through a series of resource integrations, lacking resources is a challenge.

Lack of resource: does the seeker feel they have access to the necessary resources required to progress

And typically we’re talking about lacking:

- knowledge of the necessary activities for making progress or the correct sequencing of those activities.

- skills and knowledge needed to execute one or more of those progress-making activities.

- other vital operant resource, such as creativity, physical strength, and more.

- operand resources, like natural resources in the environment or goods*, essential for certain activities.

- time.

* an operand resource that freezes specific skills and knowledge for distribution and which are unfrozen during a resource integration.

Progress seekers often engage with progress propositions to minimise their lack of resource progress hurdle. However, that has implications.

implications of progress propositions

Progress propositions aim to minimise a seeker’s lack of resource progress hurdle. They offer supplementary resources to relieve the categories we mention above. Specifically, they consist of two resource bundles:

- a proposed series of progress making activities

- a resource mix of employees, systems, data, goods, physical resources, and locations, tailored to the proposition

However, it’s important to note that a progress proposition may not always succeed in lowering the hurdle adequately. First it may not offer all the resources required. Secondly, it may introduce new lack of resource.

And, interestingly, offering a proposition gives rise to five new progress hurdles. These come from the need for the seeker to integrate with resources provided by another party. Questions arise: Can they? Do they want to? Are they the right resources? And what is it going to cost (in terms of effort in return)?

The six progress hurdles associated with a progress proposition are:

| hurdle | description |

|---|---|

| lack of resource | as previously discussed |

| adoptability | can the progress seeker easily envision themselves using the proposition? |

| resistance | will the progress seeker resist, postpone, reject, or oppose the proposition due to perceived risks, usage conflicts, traditions, norms, or image concerns? |

| misalignment on continuum | how far apart on the progress continuum (from enabling to relieving propositions) are the proposition and what the seeker is looking for? |

| lack of confidence | does the seeker trust the proposition and the helper behind it to assist them in reaching the offered progress state? |

| equitable exchange | how many service credits does a progress seeker need to get from elsewhere to engage proposition |

These six progress hurdles are distinctive, with each seeker needing to assess them as being sufficiently low to initiate and sustain a progress attempt associated with a specific progress proposition.

Let’s explore!

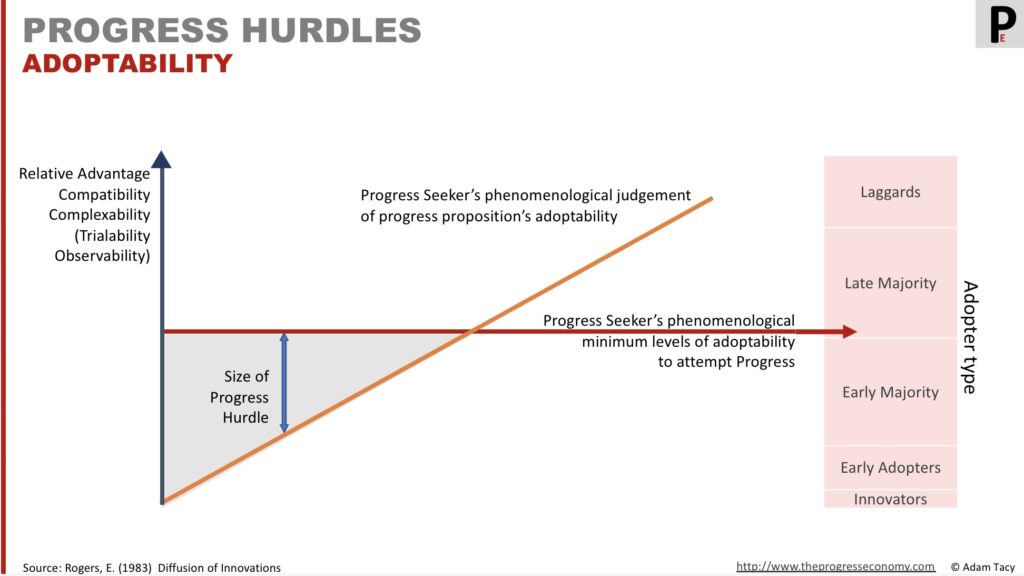

Adoptability of the Proposition

A seeker must feel comfortable and that they can effectively engage a proposition.

This hurdle is Rogers’ factors that accelerate the adoption of innovations (from his work in ‘Diffusion of Innovations‘). We mostly focus on his perceived attributes:

- Relative advantage

- Compatibility

- Complexity

- Trialability

- Observability

A proposition has a high adoptability hurdle if the progress seeker perceives it as having, for instance, a lower relative advantage compared to alternative propositions, low compatibility to what they are used to; and is more complex than other options. Whereas the hurdle’s height can be lowered through trial experiences or by the seeker observing the proposition in action.

Resistance to the proposition

Complementing Rogers’ perceived attributes is the concept of resistance.

Resistance: will the seeker postpone, reject, or even protest against a progress proposition due to perceived risks, usage, traditions & norms and/or perceived inages

Will the seeker resist the proposition. Several historical examples, such as Segway, Google Glass (v1), nuclear power, electric scooters, and the mechanical loom, illustrate instances where propositions faced significant resistance.

We turn to research conducted by Kleijnen et al., to understand resistance to innovation and its underlying factors. (see “An exploration of consumer resistance to innovation and its antecedents“)

They identify a hierarchy of factors contributing to resistance and an associated resistance hierarchy: postponement, rejection and opposition.

The higher the seeker perceives a proposition on this hierarchy, the greater the height of this hurdle.

Mis-alignment on the progress continuum between Proposition and seeker’s desire

Progress propositions sit on a continuum stretching between enabling to relieving propositions. The defining characteristic being which actor performs the majority of the progress-making activities.

A seeker also takes a desired position on the continuum for the progress attempt they about to undertake.

Misalignment on continuum progress hurdle: how far apart on progress continuum – of enabling to relieving propositions – are the proposition and what the seeker is looking for

The ‘misalignment on Progress Proposition Continuum’ progress hurdle reflects the extent of disparity between the seeker’s desired position on the continuum and the actual location of the proposition.

Put simply, the hurdle is highest if the seeker and proposition find themselves at opposite ends of the continuum.

Lack of confidence in the proposition

Seekers must have confidence that an offering will assist them in making progress. In both the actual proposition and in the helper.

a progress seeker should have confidence that the progress proposition (and progress helper) can help them make the progressed offered

Lower confidence means a higher barrier. Helpers can attempt to lower this barrier in various ways (including branding).

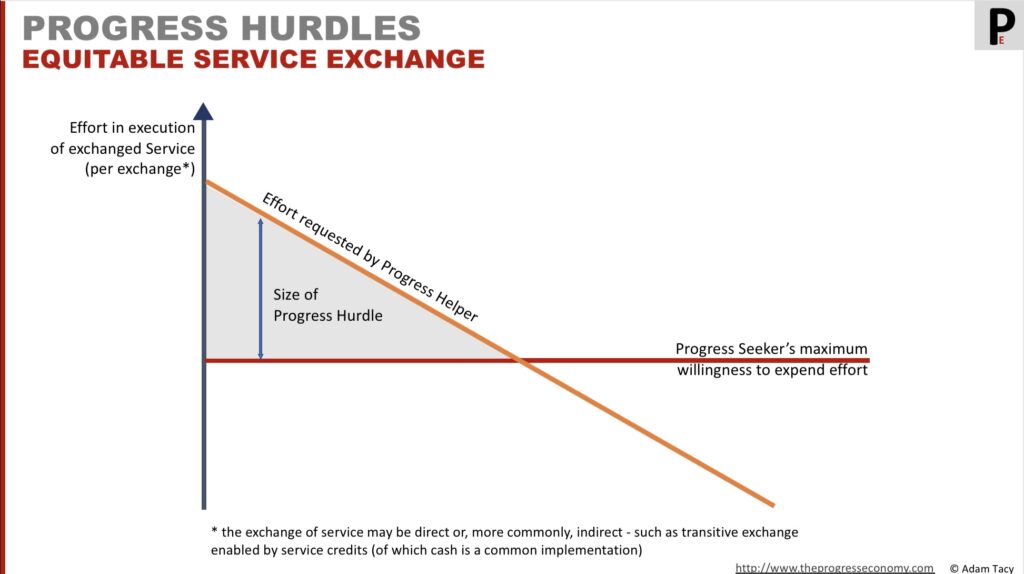

Equitable exchange

Finally we have a slightly more complicated hurdle to explain. The equitable exchange progress hurdle.

It stems from the service-dominant logic observation that we exchange service rather than the traditional goods-dominant exchange of value. You do something for me and in return I do something for you. Which implies that both parties are expending effort.

Such an exchange should be equitable, that is, each actor needs to feel the other has expended an acceptable level of effort in helping them. Note this does not mean it has to be equal.

Equitable exchange: a progress seeker needs to feel they are not being asked to perform too much effort (service) elsewhere in order to gain the asked for service credits to engage a progress proposition

Practically, service exchange is often indirect and enabled by service credits. I do something for you and get service credits in equitable exchange. I could use those credits with you to get your service at some point later. Or, I could use those service credits in an equitable exchange with another helper.

This way we explain price and the role of cash in the progress economy. Additionally, this hurdle opens the door to business model innovation – subsidising, subscription, freemium etc.

What about inconvenience?

One hurdle you might argue is missing is “inconvenience”. A service that is inconvenient is less likely to be engaged, surely.

But, what is convenience? Intuitively we might say it is something that saves us time and effort. Farquhar and Rowley have a detailed discussion on this question, arriving at the following definition:

The convenience of a service is a judgement made by consumers according to their sense of control over the management, utilization and conversion of their time and effort in achieving their goals associated with access to and use of the service.

Farquhar, J. D. and Rowley, J. (2009) “Convenience: a services perspective”

This is captured in the hurdles we have just discussed.

Relating to value

In the progress economy we see value emerges from progress. Therefore, anything that hinders progress also reduces value. And this is what progress hurdles potentially do.

This is why propositions arise and are of interest. They primarily look to reduce the lack of resource progress hurdle, giving the promise for better progress; and therefore a seeker to realise more value.

Relating to Innovation

Simply put, reducing progress hurdles is a rich zone for innovation. Doing so we can better make existing progress and/or make more progress.

Let’s progress together through discussion…