What we’re thinking

Service is eating the world, but goods may still be strategic. The Progress Economy gives you the tools to decode this shift, manage it intelligently, and uncover why goods still matter. Rethink your proposition, not by what it is, but by how your customers truly want to progress: to be enabled or relieved.

To adapt Andreessen Horowitz’s famous line:

We’re experiencing a shift from a goods economy to what many are calling the service economy – and there are compelling reasons behind the trend.

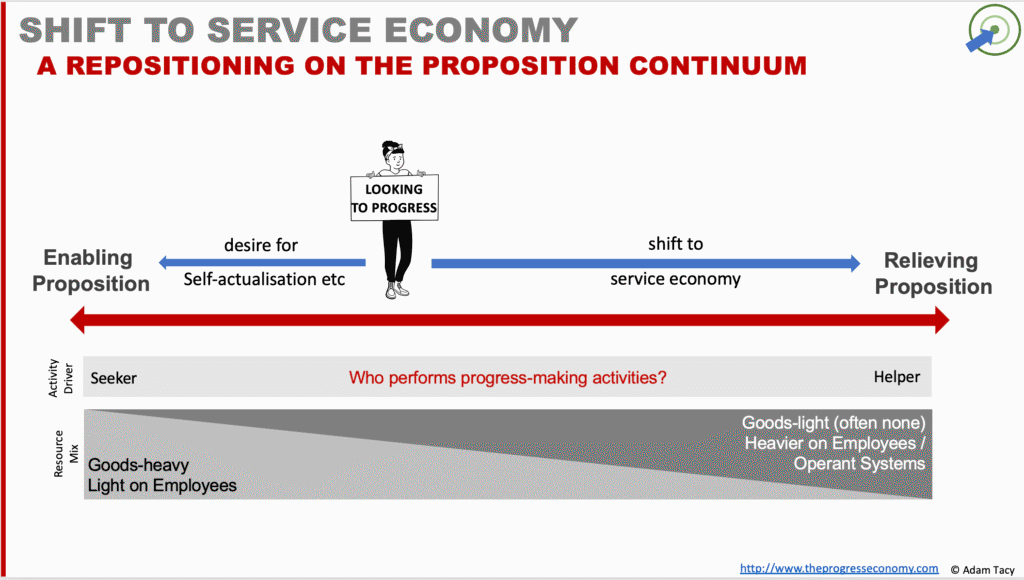

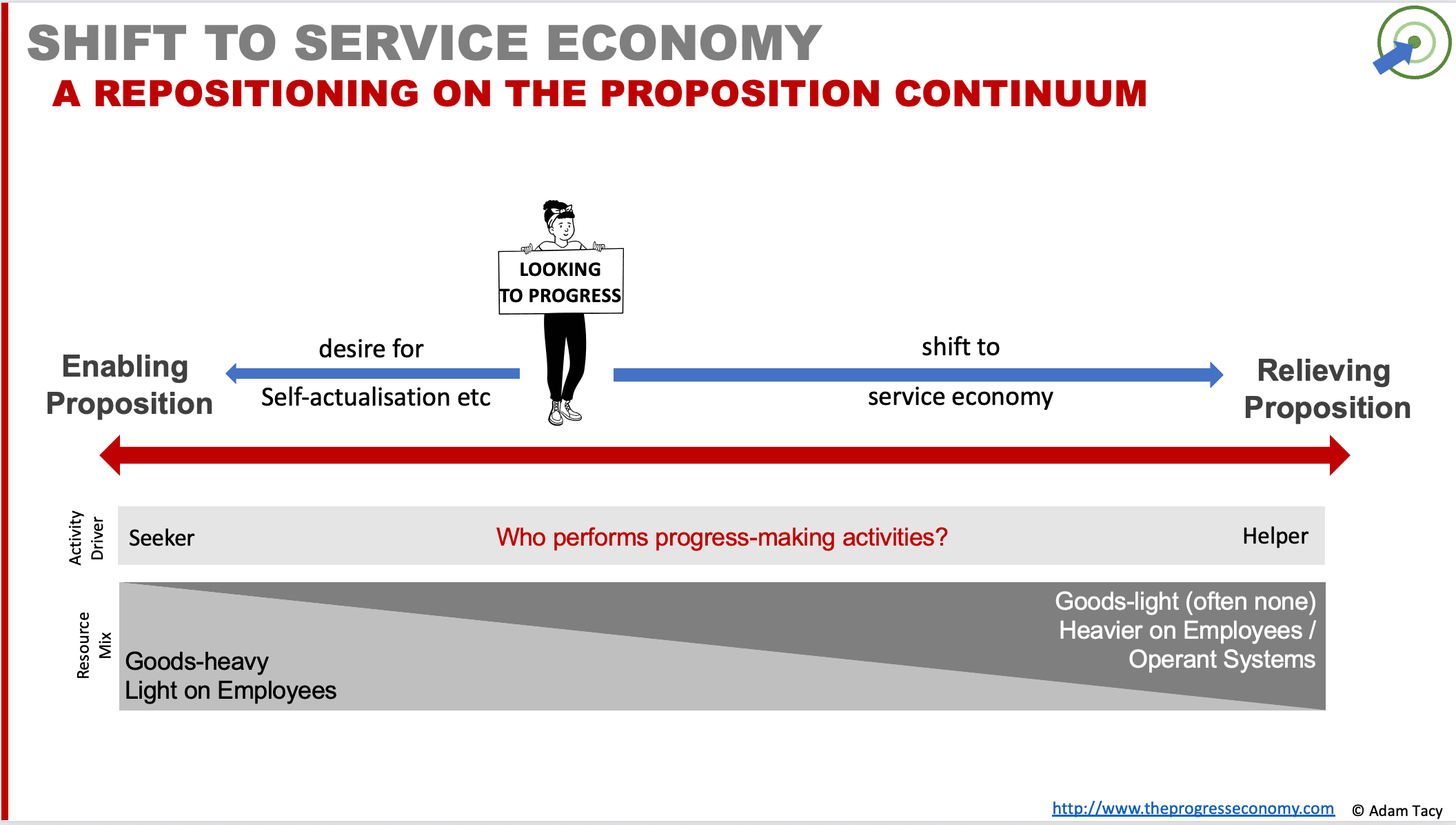

In the Progress Economy, this is simply a slide of the Progress Seekers’ positioning on the proposition continuum towards relieving propositions. If you miss that, you increase the continuum misalignment progress hurdle.

But progress-first thinking also reveals an important nuance: some Seekers deliberately slide the other way. They seek self-actualisation as part of their progress. They are the home brewers, the parents nurturing sourdough starters, the people who find joy in deep-cleaning their own homes, home mechanics, masterchefs in the kitchen, etc. For them, enabling propositions are more attractive.

Read on to uncover the strategic forces behind the rise of services and how a progress-first lens can help you position your proposition where your customers actually want it.

The Shift is happening

All aboard the relentless “shift” to services and the service economy!

We’ve come a long way since Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations view (1776), where services were dismissed as non-productive. Today, services are the dominant force in most economies, far outpacing manufacturing – the traditional stronghold of value creation (aka the goods economy).

The OECD was already noting back in 2000:

“manufacturing [is] slipping to less than 20% of GDP and the role of services rising to more than 70% in some OECD countries”

OECD, 2000

Consider the service related revenue numbers for the following companies from 2024:

- Just Eat (food delivery): €5.1B

- Uber (mobility & delivery): $44B

- Apple’s services division: $85.2B – now over 22% of its total revenue

- Securitas (security services): SEK 161.9B (~$20.2B)

- Handelsbanken (banking): SEK 62.3B (~$7.8B)

Quite sizeable, right?

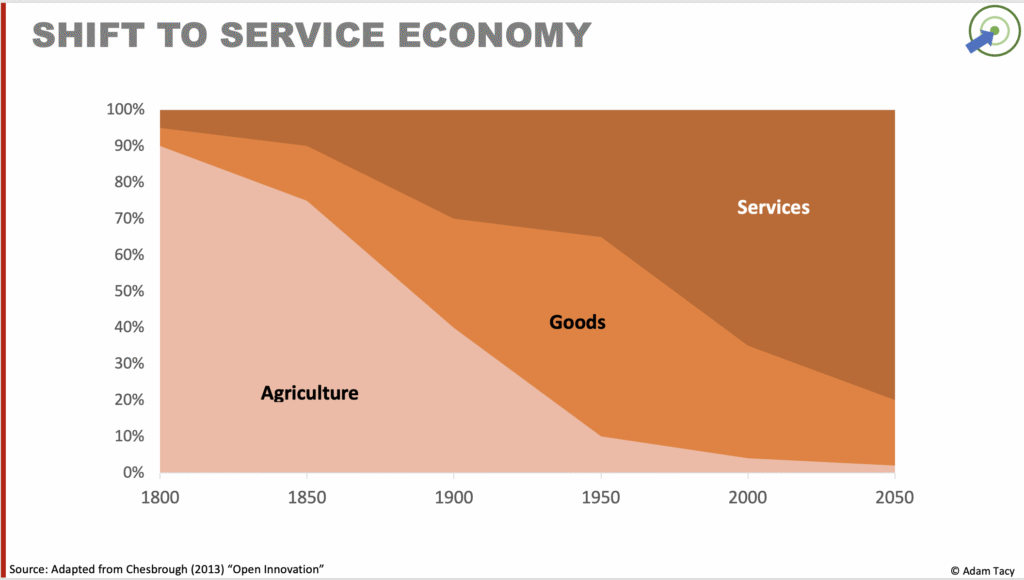

Haskell and Westlake’s 2018 “Capitalism without Capital” argue that intangibles – which we can loosely categorise service – are a (large) hidden component of economies. Henry Chesbrough’s Open Service Innovation went further, projecting that the U.S. economy would be 80% service-based by 2050.

And this isn’t limited to the “developed” world. In Nigeria, services made up 50% of the economy in 2010. By 2017, that figure had climbed to 55.8%.

The direction of travel appears clear. Nearly 15 years ago, Andreessen Horowitz said that software is eating the world. We can rewrite that today as:

Service is eating the world

Of course, things can go too far. As we now know (and probably really knew all along) the world does not need a monthly subscription-based juicing packs system!

What’s behind this shift?

Why the shift

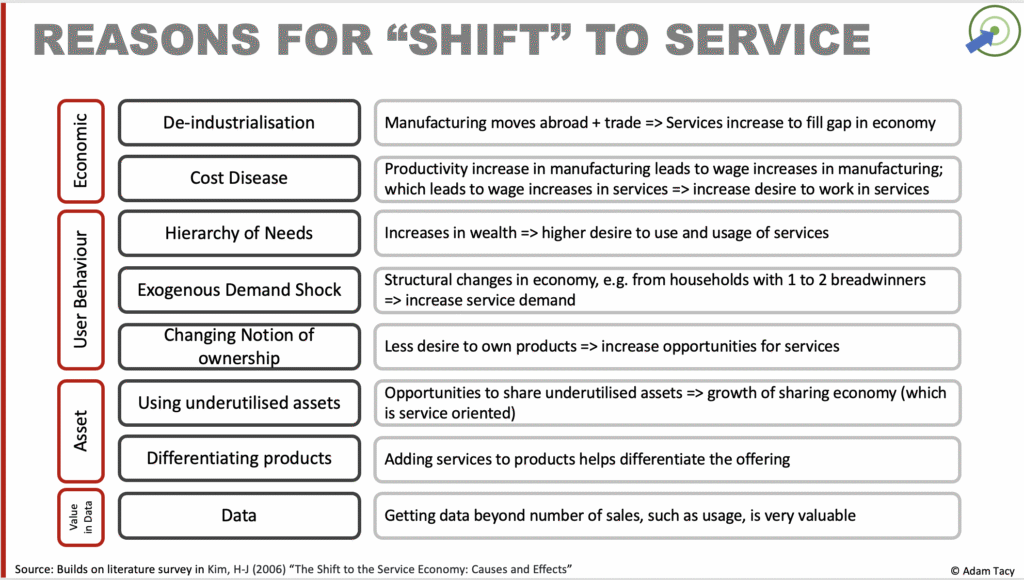

The shift from a goods-based to a service-led economy isn’t driven by one factor. It’s a structural transformation shaped by multiple converging forces — some passive, some active, many strategic. Kim’s useful 2006 paper, The Shift to the Service Economy: Causes and Effects, surveyed the literature and identified two passive and two active causes. But the real picture is broader.

I’ll group all these reasons into four broad categories:

- Economic drivers

- Changes in user behaviour

- Asset utilisation opportunities

- The strategic value of data

These forces are illustrated in the accompanying visual, and explored below in more detail.

Economic drivers

Kim’s passive forces – deindustrialisation and cost disease – explain some of the macro backdrop.

As manufacturing moves offshore, services fill the domestic gap (Wood (1995) “How Trade Hurt Unskilled Workers” and Freeman (1995) “Are Your Wages Set in Beijing?“). This is deindustrialisation. Although the full impact of this is debated.

Baumol’s cost disease hypothesis offers stronger evidence. As productivity rises in manufacturing, wages increase. Services, even without productivity gains, must raise wages to stay competitively attractive to employees. The result: expanding service sectors wages, and an expanding service sector. See Baumol (1967) “Macroeconomics of Unbalanced Growth: the Anatomy of Urban Crisis” and Baumol et al. (1985) “Unbalanced Growth Revisited: Asymptotic Stagnancy and New Evidence“)

Changes in user behaviour

Demand-side shifts also fuel growth in services, of which the first two below are Kim’s active reasons.

As societies become wealthier, people don’t just want more, they want better. They climb Maslow’s hierarchy and begin prioritising services that save them time, reduce friction, and deliver emotionally resonant experiences.

There are also social shifts – exogenous demand shocks, like increasing dual-income households – which trigger sustained demand for services. Inman (1985) found such shocks explained nearly 70% of U.S. service sector growth between 1966 and 1981.

Layered on top is a growing cultural shift: ownership is losing its appeal. Increasingly, consumers prefer access over assets; using rather than owning. Spotify, Netflix, and Kindle rent us content and have effectively replaced ownership of CDs, videos, and books. Lovelock & Gummesson’s “Whither Services Marketing? In Search Of A New Paradigm And Fresh Perspectives” give the following as examples of non-ownership services:

- Network access and usage

- Rented goods services

- Place and space rental

- Labour and expertise rental

- Physical facility and usage rental

Asset utilisation opportunities

Chesbrough, in Open Service Innovation (2013), notes that services are growing due to making use of underutilised assets. Idle capacity – cars, rooms, processing power – is now monetised. Assets are being reimagined as service platforms. This powers the sharing economy.

But the trend is wider. Firms are increasingly differentiating via servitisation: wrapping services around products to deliver outcomes, not just tools.

Take Rolls-Royce’s “Power by the Hour.” Instead of selling engines and separate maintenance, they offer propulsion as a service. Airlines buy guaranteed uptime at a fixed rate. For customers, this means performance certainty. For Rolls-Royce, it drives recurring revenue and incentivises efficiency (see this Harvard overview for interesting details).

Strategic value in data

Services don’t just deliver “value” – they generate artefacts that are of great use: data.

Every interaction yields insight into usage, context, and need. This shifts firms from lagging to leading indicators — from transaction data to real-time feedback. Service firms can personalise, optimise, and respond dynamically. The expected result: smarter decisions, faster innovation, and deeper customer relevance.

The shift through the progress economy lens

Traditionally, we frame the economy as a contest between goods and services. This comes with an explicit bias that goods are inherently superior, while tangible, reliable, and inherently superior, while services are inconsistent, intangible, and difficult to scale (they require customer involvement, delivery is inseparable from consumption, and we can’t create an inventory of them). These assumptions linger in many discussions about the shift to a service economy.

But in the Progress Economy, we draw a vital distinction: between services (plural) and service (singular). The former refers to categories of offering. The latter, which we focus on, describes the act of helping someone make progress. This shift in perspective leads us to the concept of the progress proposition continuum, where every offer sits somewhere between enabling and relieving, depending on how much progress the customer must make themselves.

Seen through this lens, the so-called “service economy” isn’t just about sectoral rebalancing. It’s about Seekers gravitating toward relieving propositions that reduce friction, save time, and offer greater certainty. That shift naturally reconfigures the offered resource mix : from asset- and goods-heavy to system- and people-intensive. The reasons for the shift are those we’ve just discussed.

Is the rise of services the death knell for goods? Not quite. Goods still play a vital role. A handyman may offer a relieving proposition to the homeowner, but they, themselves, still need physical tools to deliver that outcome. Likewise, Rolls-Royce’s “Power by the Hour” still depends on high-performance engines; teleportation isn’t here yet, and even then, we’ll be manufacturing teleporters.

It’s not a one way shift

The progress-first lens also reveals something that can be missed otherwise: not all Seekers want to be relieved. Many actively seek to be enabled. Think of the home chef mastering complex recipes, the hobbyist brewer, the DIY furniture maker. For these individuals, the satisfaction lies in some combination of doing, self-actualisation, and friends and family going “wow, you did this?!”.

This underscores the need to understand all three aspects of progress:

- Functional – getting the job done

- Non-functional – how it’s experienced, what is the seeker looking to achieve beyond just function

- Contextual – fit with individual circumstances

Where a Seeker sits on the proposition continuum – from full enablement to full relief – is shaped by their intent. Spotting that nuance can reveal unmet needs and overlooked opportunities, particularly where competitors are offering propositions misaligned with actual progress sought.

What should I be doing?

There are 5 key moves you should be making:

- Reposition around progress, not products

- Map the position of your potential customer(s) on the progress continuum

- Strategically innovate your resource mix to match that position and reduce the continuum misalignment progress hurdle

- Embed data collection in your proposition to inform on progress and feed future sales/innovation activities

Wrapping up

The rise of service(s) isn’t just an economic trend, it’s a reflection of deeper shifts in how people seek and experience progress. By examining these shifts through a progress-first lens, leaders can move beyond surface-level trends and discover the true drivers of customer behaviour. The Progress Economy reframes the conversation – not around goods or services, but around how propositions help people move forward, functionally, emotionally, and contextually.

This has direct implications for growth strategy, value creation, and competitive differentiation. Understanding where your customers sit on the proposition continuum – whether they want to be enabled, relieved, or something in between – reveals new market spaces and helps avoid misalignment that stifles traction. Most importantly, it gives your organisation a more dynamic, adaptive way to shape value in a world that’s shifting faster than traditional business models can respond to.

For CEOs and innovation leaders, this isn’t an abstract theory – it’s a strategic tool. It can guide investment decisions, influence go-to-market strategies, and unlock new product-service hybrids that better align with customer intent. It opens a richer dialogue between demand and design, customer need and corporate capability.

If service is eating the world, then the Progress Economy explains why. And in doing so, it equips you with the frameworks to lead – not just react – in a world where value is being redefined. The next step? Rethink your proposition not by what it is, but by what progress it enables.

Let’s progress together through discussion…