Stop asking “What product should we build?” and start asking “What capabilities do our customers lack that is limiting their progress?”, and then package those in resources that deliver them best in the context of the Seeker’s progress.

What we’re thinking

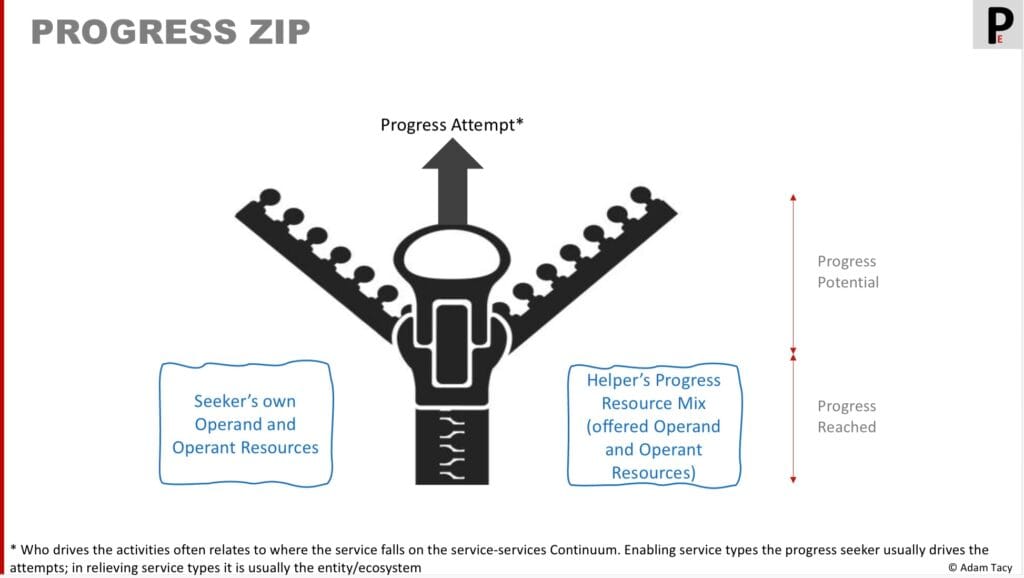

Progress is made when we successfully integrate resources that carry the necessary capabilities. It stalls when we mis-integrate, have the wrong type of resource to Seeker’s expectations, or lack resources carrying the needed capabilities (that is, we lack the needed capabilities).

But what are resources? The literature, and our daily linguistic short-cuts, introduce confusion! So let’s be precise:

resources: carriers of capabilities

We are typically thinking of the Seeker themselves and items in the Helper’s proposition-specific resource mix (the Seeker facing employees, systems, data, goods, physical resources, locations). They are also the internal facing carriers of capability within organisations (departments, people, systems)

This definition goes hand-in hand with that of capability:

capability: a quality of a resource that is used in making progress

Our clear distinction between resource and capabilities comes as a consequence of Levitt’s famous “people don’t want a 1/4 inch drill, they want a 1/4 inch hole” . Seekers need a 1/4 inch hole making capability – which can be carried by a variety of resources. Since different resources can carry the same capability there is an innovation level: they can be swapped.

By decoupling resources from capabilities, leaders can:

- Align offerings to Seeker preferences and avoid progress continuum misalignment.

- Expand the range of possible propositions.

- Swap in new resources to unlock efficiency or differentiation.

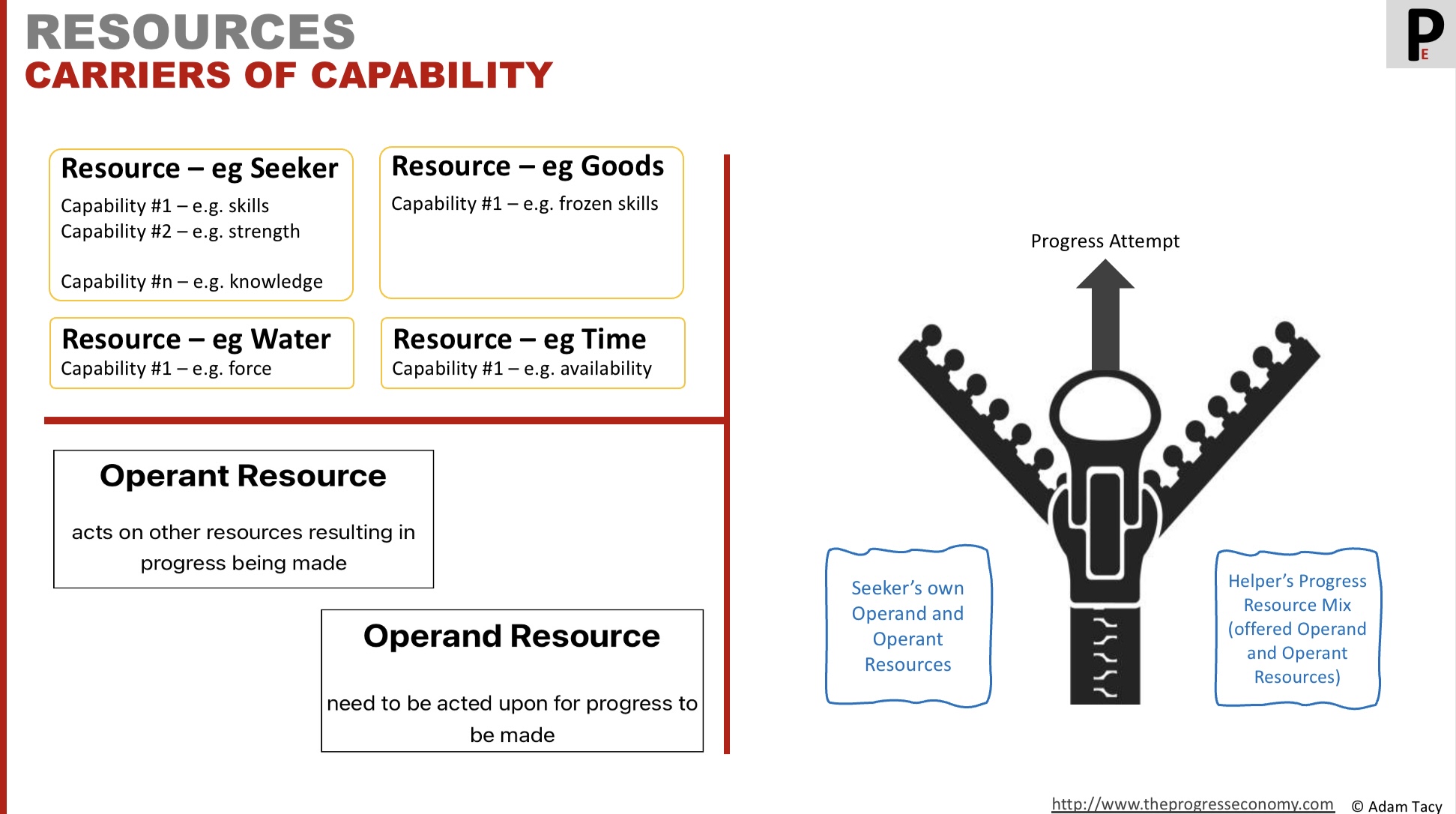

Finally, we categorise resources not as tangible and intangible (the traditional way) but rather as how they are used in making progress. Operant resources act on other resources to make progress and operand resources need acting upon in order for progress to be made.

What are resources?

In the Progress Economy, resources are the raw materials of progress. Whether it’s a call centre agent resolving an issue, AI generating content, sunlight powering a solar panel, a hammer driving a nail, or the R&D department discovering new solutions – progress happens when we purposefully, and successfully, integrate the right resources to move from one state to our more desired one.

Sometimes integration is simple. Sometimes it’s complex. But the goal is always the same: making progress.

As Vargo et al (2010) note, human ingenuity continuously creates “countless resources” that reshape markets and societies. Just as a Seeker’s progress origin and progress sought evolve, new resources are sought, emerge, or are borrowed across industries and markets to meet them. Or spark new possibilities altogether.

De Gregori, in “Resources are not; they become: an institutional theory” makes a critical point: resources aren’t fixed. We redefine them based on how we learn to apply them. This evolutionary view of resources is central to economic and societal progress.

Defining resources – the traditional view

Traditionally, in Hunt’s resource-advantage theory, resources are described as “the tangible and intangible items available to an actor” (Hunt, 1997).

the tangible and intangible entities available to an actor

Hunt, S. (1997) “Competing Through Relationships: Grounding Relationship Marketing in Resource-Advantage Theory”

In this framing, resources include goods and infrastructure as well as intangibles like expertise, brand equity, and relationships.

However, we often skew this framing towards tangibles as inherently preferable. We tend to evaluate resources based on what they are rather than what they do. This bias feeds the persistent, but unhelpful, goods-versus-services (plural) debate. It also ignores the rising importance of intangibles in modern economies, driven by scalability, spillovers, sunk costs, and synergies (Haskell & Westlake, 2017, “Capitalism without Capital: the rise of the intangible economy“), alongside the ongoing shift to the service economy.

Consider music: is a CD (tangible) inherently “better” than a digital stream (intangible)? And how does either compare to a live performance (another intangible)? In the Progress Economy, the answer depends entirely on the progress the Seeker is trying to make—not only in functional terms, but also non-functional and contextual.

Defining resources – the progress economy view

The Progress Economy turns the lens around. Instead of asking what is this resource – tangible or intangible? – we ask how does it enable progress? In other words: what capabilities does this resource carry?

What matters is not the asset itself, but the role it plays in enabling progress. Peters et al. (2014) lead us to this view:

…no tangible or intangible item represents a resource in its own right; rather a resource is a “property of things…”. In this sense, a resource is a carrier of capabilities

Peters L.D., Löbler, H., Brodie R. and Briedbach, C. (2014) “Theorizing about resource integration though S-D Logic”

De-emphasising the tangible–intangible divide, the Progress Economy defines a resource simply as:

resource: a carrier of capability that can be integrated in one or more progress-making activities.

Common resources in the Progress Economy include Seekers themselves and the items offered in a proposition-specific resource mix from a Helper (such as employees, goods, locations, and data). Some resources are nature-based, like water, and may or may not be under human control. Others, like weather, lie entirely outside human control, yet may still shape progress (Vargo, Lusch & Akaka, “Advancing service science with service-dominant logic“).

When we look more closely at how resources are used, we will classify them based on their role in making progress (borrowing from Constantin & Lusch, 1994)

acts on other resources resulting in progress being made

need to be acted upon for progress to be made

We’ll find that at least one resource in a resource integration – a progress-making activity – must be operant…otherwise no progress is made.

Relation to Capabilities

We see resources as carriers of capabilities – which we define as:

capability: a quality of a resource that is used in making progress

What do we mean by this? Well, capabilities are properties of a resource that are used in making progress. Think of skills, strength, availability. It is those capabilities which we apply through resource integration.

| resource | example capabilities |

|---|---|

| seeker | skills, strength, time |

| car | transportation |

| generative AI system | knowledge, scalability |

| R&D department | knowledge, skills, innovativeness |

| wind | power |

Here’s an example. A Seeker might travel 100 km by applying their driving skills to a car’s transportation capability; in doing so, they are integrating themselves and the car. In everyday language, however, we are often less precise when describing this, saying simply that the Seeker applies their driving skills to the car; or even simpler, the Seeker “uses” the car. Such linguistic shortcuts can blur the distinction between resources and capabilities.

Distinguishing between resource and capability

In everyday business language, “capability” and “resource” are often used interchangeably. The Progress Economy treats them as distinct. We do so because different resources can carry the same capability – and can therefore be substituted. This is a powerful source of innovation.

As we explore when looking at capabilities, Levitt’s famous observation in Marketing Myopia illustrates the point:

People don’t want to buy a quarter-inch drill. They want a quarter-inch hole!

Levitt “Marketing Myopia”

To get that hole, the Seeker needs the capability to make one, which can be carried by different resources: a drill, certainly, but also a handyman, and others. Here, we see de-emphasised distinction between a goods (the drill) and a service (the handyman) – we have no unhelpful services vs goods debate. Either resource can deliver the desired outcome — and replacing one with the other can completely change the business model.

What ultimately matters is the type of resource the Seeker prefers to engage. This choice is strongly guided on whether they are looking to be empowered or relieved.

- If they want to be empowered, they will gravitate towards propositions that give them the tools – often goods-based, like the drill.

- If they want to be relieved, they will favour propositions that do it for them – often service-based, like hiring the handyman.

Our progress propositions – offerings of supplementary capabilities – live along an empowering–relieving continuum, and a mismatch between where the Seeker and the proposition sit on that continuum is a progress hurdle: continuum misalignment. If you want someone to make that hole for you, offering you a hammer is a misalignment.

In an organisational context, the same principle of interchangeable resources applies. Marketing capability, for example, could be carried by a dedicated marketing department, distributed across employees in business units, or embedded in a combination of systems and people. Similarly you could own those resources yourself, or outsource them.

Editing below here

How resources help make progress

Progress doesn’t just happen. It depends the right mix of capabilities (carried by resources) being available, used in the right way, and at the right time.

Technically, progress is made when capabilities are applied. That happens through resource integration.

In fact, we define our basic progress step – a progress-making activity – as the integration of two or more resources. And a progress attempt is simply a sequence of these.

Seen this way, the foundation of any failure to make progress is usually straightforward: a lack of or misaligned resource. That missing piece could be a tool, for example, but also knowledge of the progress-making activities, or skills to perform them.

This is where progress propositions offered by a Helper come in. We define them as bundles of supplementary resources: a proposed series of progress-making activities, supported by a specific resource mix designed to be integrated with the Seeker’s own. These resources might include employees, systems, data, tools, physical environments, or locations. Who performs the majority of the integrations positions whether your proposition leans toward the enabling or relieving end of the proposition continuum.

Here’s the interesting part: for integration to happen, at least one resource must act on the others. Without action, there’s no integration—no movement. This distinction leads us to a shift in how we categorise resource in the progress economy.

Operant and Operand resources: different ways to progress

Forget the traditional distinction between tangible and intangible resources. That just tells us what something is, and leads to unproductive debates – products vs. services (plural) – when what really matters is how a resource works.

In the Progress Economy, we classify resources by their role in progress-making:

acts on other resources resulting in progress being made

need to be acted upon for progress to be made

These definitions build on the foundational work of Constantin and Lusch (1994) in “Understanding Resource : How to Deploy Your People, Products and Processes for Maximum Productivity“, but are adapted here to focus on how progress is made.

Let’s ground this with a simple example. In the progress attempt “John drives the car to get to the office”:

- John carries the knowledge and skill of how to drive. He applies those capabilities on the car. He’s the operant resource.

- The car has the capability of movement, but it requires John to activate it. It’s an operand resource.

However, a resource’s classification isn’t fixed. It can depend on the capability in question. Consider the natural resource of water:

- used to drive a turbine, water is an operand resource – its movement acts upon the turbine to create energy

- used to quench thirst, water is an operant resource – it must be consumed (acted upon)

Similarly a Seeker is often an operant resource, acting on other resources to make progress. But they can be an operand resource in cases of progress on their body, such as medical or being tattooed.

One thing is for sure. Without at least one operant resource, nothing integrates; no progress is made; no value emerges. Two cars parked side by side don’t move themselves.

Both Seekers and Helpers may have operand and operant resources. And they acquire them through various strategies, which I’ll expand on in these following articles.

Allocative control: who decides when a resource is used?

A dimension of resources is allocative control: the authority and freedom to decide when and how a resource is put to work.

Allocative control (of a resource): the ability to determine when a resource is used.

This distinction becomes important when resources are shared or temporarily transferred. Allocative control doesn’t require transferring ownership, only control over when and how the resource is deployed.

Why does this matter?

It frames how we think about goods and data within a Helper’s proposition. For example, a resource seen as a goods implies permanent transfer of ownership when acquired. Whereas a physical resources implies temporary transfer of allocative control. You can do what you want with a hire care when you are hiring it, but once the hire ends you no longer have any allocative control. With digital goods we often observe Helpers treating them as physical resources rather than goods. Take your playlist on Spotify, you don’t own those songs, you are just have allocative control until Spotify decide to remove them.

Strategic Benefit: why better resources mean better business

To a Seeker, one resource is “better” than another if it helps them make progress better, and/or better progress.

For Progress Helpers, offering better resources is a path to strategic advantage. Superior resources drive more, and likely larger, service exchanges. As Hunt’s Resource-Advantage Theory explains, firms win by deploying better resources. Weaker players must improve by managing existing resources better, acquiring new ones, or innovating around how they’re used. (Hunt, S. (1997) “Competing Through Relationships: Grounding Relationship Marketing in Resource-Advantage Theory”).

Where Hunt speaks of advantage, Service-Dominant Logic (Vargo & Lusch) instead frames this as strategic benefit. This is a more fitting term for the Progress Economy. From our Seeker-centric perspective, they look for propositions that can help them progress better than they can themselves. Helpers should focus on helping the Seeker with that.

But what does “better progress” actually mean? It comes in two forms:

- Progress, better – Helping the Seeker achieve the same goal in a more effective way

- Better progress – Helping the Seeker reach a goal they couldn’t previously attain

Both are measured, by the Seeker, through the three aspects of progress:

- Functional – Does the resource help get the job done?

- Non-functional – Does it do so in a way that is preferred, efficient, or emotionally resonant?

- Contextual – Is it fit for the Seeker’s specific situation, constraints, and preferences?

“Better” can emerge from any one of these dimensions, or by reducing one or more of the 6 progress hurdles.

Let’s anchor this in a simple scenario: traveling 100 km from A to B.

Functionally, many resources could do the job: walking shoes, a bicycle, a private or hired car, a train, a plane, or even a Zoom call. But layer in non-functional or contextual elements, like a desire for exercise, the need to work en route, or a preference for scenic views, and the strategic benefit of each option changes.

Want achievement? Take the bike. Need to prepare for a board meeting? Book a train or taxi. Prefer flexibility and control? Use a car.

Service-Dominant Logic (Vargo & Lusch) positions operant resources – those that act on others – as the true source of strategic benefit. Unlike passive goods, operant resources adapt, respond, and interact. A handyman offers advice and judgement; a power drill does not.

However, whilst this is true for a Seeker searching for a relieving proposition, there are seekers looking for enabling propositions, and they typically offer operand resources. Additionally there is the dynamic that relieving propositions often push up the inequitable exchange progress hurdle (lazily: costs).

So, you should aim for leveraging operant resources, unless your target market is looking for enabling propositions, in which case operand resources are king for you.

This is the art of creating propositions. First fully understand the progress journey of the Seeker (origin and progress sought). Identify the capabilities they are missing or that are carried by resources not beneficial to the Seeker. From there, create, adapt, borrow resources from other industries or markets; ensuring you are minimising all the 6 progress hurdles.

Relation to value

Resources have no value. There, I said it.

They only have potential to help progress, and when used they enable progress (from which value emerges). Both potential and emerged values are comparisons of progress, predominantly made by a Seeker.

Resources have only the potential to help make progress; which is realised during resource integrations…

Seekers evaluate the potential value of resources by comparing how much progress towards their progress sought they feel they can make when integrating with it along with comparing the progress hurdles related to them using it. Emerged value comes from comparing progress reached with expectations.

As resources only contribute to progress when being used, this raises a question about resource efficiency. Which in turn leads to the sharing economy – how can we increase the usage rate of resources. That takes us onto the relation to innovation.

Relation to innovation

We can capture this more generically. A resource is a strategic benefit if it does one or more of the following:

- help make current progress potential in a better way

- help make better progress towards individual seeker’s progress sought

- reduce one or more of the 6 progress hurdles

And that just happens to be part of the progress economy’s definition of innovation.

Offering better progress

We primarily innovate resources to improve progress that can be made through resource integrations.

The overall goal of a seeker’s progress attempt is to reach their progress sought. They may attempt to use their existing resources in innovative ways, including in novel combinations.

Alternatively a seeker looks to a progress helper for supplementary resources. The helper may innovate their resources in order to:

- get their progress offered to closer match individual seeker’s progress sought

- better reach their current progress offered

- reduce one or more of the six progress hurdles

The helper offers some of their resources to the seeker to integrate with in the form of the progress resource mix.

A progress proposition includes proposed progress-making steps. These are also ripe for innovation to meet the same goals as above.

Leveraging skills from other markets/industries

Seekers are constantly attempting to progress with many things. This means they experience many markets and industries that are different than yours. They are learning new skills and gaining new knowledge there.

Innovators should be aware of what seekers are learning elsewhere and identify what can be “carried” into the helpers resource integration proposals. Think of the pervasive multi-uses of QR codes, as an example.

Educating seekers

We saw above (Alves, Ferreira, and Fernandes (2016)) that educating/training seekers increases co-value creation. How can you educate your seekers to improve resource integrations in your proposal? Where we should think of education in its broadest sense (one-one, group, physical, virtual, trial usage, AI instructors/tools and so on)

Increasing resource usage efficiency

We saw that resources are only creating value when used in acts of integration. Think of it this way: a screwdriver or an employee are not contributing to any progress (creating no value) when they are not used.

There’s even an academic debate on whether they can be called resources when not in action. Rather than jump down that rabbit hole, let’s summarise this as saying innovation should look at how to maximise use of resources. Which hints to subscription or sharing models – as long as allocation does not become a problem…

Let’s progress together through discussion…