Rediscovering that service is the true nature of exchange isn’t just clarifying, it reveals powerful levers for innovation.

What we’re thinking

We live in a world where service (singular) exchange – helping others make progress in order to get help making our own progress – is the true engine of economic activity.

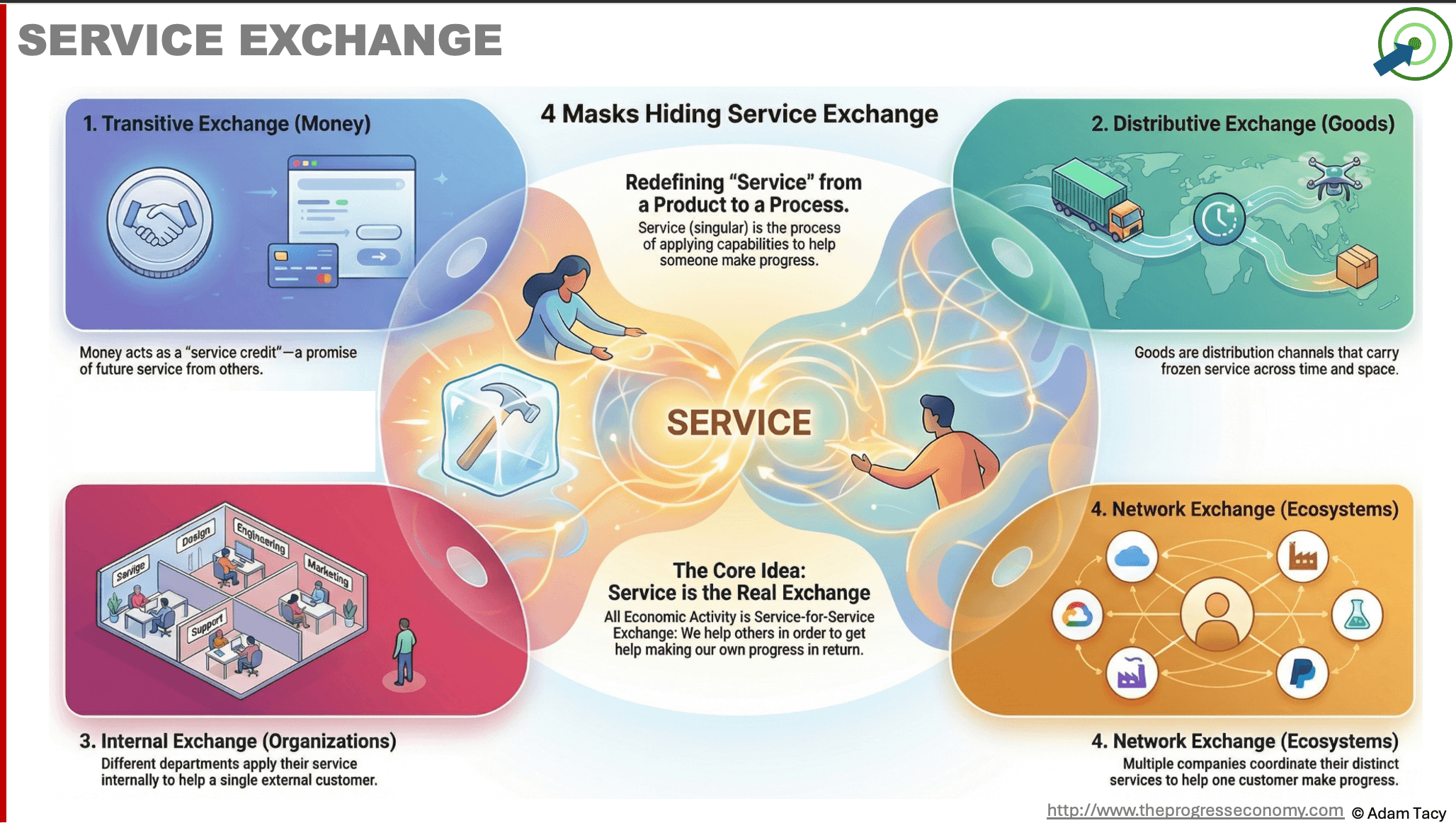

Yet we comfortably see our world as one where we exchange value – cash for goods (or more formally: value-in-exchange). It’s an illusion, where indirect exchange, such as through goods or transitive exchange (enabled by service credits; an example of which is cash) often mask the true service-based nature. Whilst value-in-exchange has been wildly successful, building our economies, we know it has blindspots that are increasingly obvious; ultimately leading to our current innovation, sales and growth problems.

To accelerate past those problems we benefit from getting back to the true nature of exchange, which requires several foundational shifts in our thinking:

- Service (singular) is defined as applying capabilities for someone’s benefit (this is differentiated from services (plural)).

- Goods freeze service allowing them to be transported and unfrozen when and where needed through acts of resource integration

- Service exchanges are often indirect (transitive, through goods, internal or network)

- Service credits often lubricate exchanges and mediate effort and time differences – physical cash has been a successful implementation

- Price signals the effort a Progress Helper expects in return for helping you. That return may come over time, across several interactions, and from other parties than you

- Service exchange – that is effort applied – is expected by all involved parties to be equitable (not necessarily equal=). After all exchanges are complete, all parties are happy they have had the service they needed in exchange for the service they have applied.

It should be noted we’re not describing/promoting a bartering economy; price, money, profit and markets absolutely have their place.

Why this matters

These shifts:

- dissolve the limiting goods vs service debate – we can cure Levitt’s marketing myopia (customer want a 1/4 inch hole, not a 1/4 inch drill)

- create room for business model innovation – subscriptions, freemium models, cross-subsidies – since effort and return (price) don’t have to be linear or immediate.

- reveal an inequitable exchange progress hurdle – where a Seeker feels too much effort is being requested in exchange for helping them reach towards their progress sought.

Rediscovering the true nature of exchange isn’t just clarifying, it reveals fundamental levers for innovation

Rethinking economic growth: beyond value exchange

A progress-first view of the economy moves us beyond traditional value-in-exchange thinking and squarely into Vargo and Lusch’s service-dominant logic, which forms part of the foundation layer of the progress economy. Their core assertion is unambiguous that exchange is, at its core, service-based:

Service is the fundamental basis of exchange

#1

At its simplest: I perform a service for you and you perform one for me.

This reframing matters because value-in-exchange focuses on outputs – cash for products – while service exchange is fundamentally about process and effort. Following Vargo and Lusch, we will distinguish between service (singular) and services (plural). Service (plural), treated as outputs and positioned as the counterpart to goods, pull us into the unproductive goods vs services debate. Service, by contrast, refers to the application of capabilities for someone’s benefit. That distinction forces a rethink of several familiar concepts, not least price. If no value is being exchanged, price can no longer mean “the maximum a customer will pay for a product.”

Service-dominant logic also tells us that direct exchange is often masked by indirect exchange – the four types of which we will name: transitive, distributive, internal and network.

Indirect exchange masks the fundamental basis of exchange

#2

Transitive exchange, for example, is where I perform a service for you; you give me service credits; and I use those service credits to get a service from a different Helper.

Take transitive exchange as an example. I perform a service for you. You give me service credits. I then use those credits to obtain service from another Helper. The direct service-for-service exchange remains, but it is less immediately visible.

It is the combination of service credits and indirect exchange that creates the illusion of value-in-exchange. A model that has been wildly successful, but whose blind-spots are increasingly impactful (stalling growth and fuelling the innovation problem).

It is the combination of service credits and indirect exchange that creates the powerful illusion of value-in-exchange. That model has delivered extraordinary scale and efficiency, but its blind spots are becoming increasingly impactful (stalling growth and fuelling the innovation problem).

But make no mistake, this is not a description of a barter economy. Price, profit, markets etc all have a place, though now described in terms of effort in service, rather than hard to define value.

We can logically build up towards this understanding of service exchange, starting with clearly defining what service is.

What is service?

Just like Vargo & Lusch in their “From Goods to Service(s): Divergences and Convergences of Logics” (Vargo & Lusch (2008)), we will draw a distinction between services (plural) and service (singular).

Services (plural)

a unit of output, the dual of goods (products = goods + services)

Service (singular)

the process of helping make progress (goods enable service to be transported)

The plural definition is likely the more familiar as it is our traditional view; whereas it is the singular definition that is of interest to us in the progress economy. Let’s look at them both and importantly, why we shift to using the singular version.

Services (plural) ❌

Services (plural) are viewed as units of output – the counterpart to goods. This perspective classifies goods and services as distinct categories, with services often seen through the lens of the IHIP attributes described in Parasuraman and Berry’s “Problems and Strategies in Service Marketing”, commonly known as the “5Is” of services. They are:

- Inconsistent – services vary in delivery and quality; whereas goods are consistent and repeatable

- Intangible – while goods are tangible items (let’s ignore digital goods temporarily…), services lack physical form

- Inventory – we can stock and store goods, but service cannot be inventoried

- Involvement – Services require customer involvement; goods don’t need those customer interactions during production

- Inseparability – Service provision and consumption happen simultaneously, unlike goods, which can be manufactured in one place and consumed elsewhere

This rather casts services as inferior to goods. Something we can find back in Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations (1776), and reinforced through a manufacturing bias ever since. Goods are seen as primary wealth generators, while services play a secondary role. Vargo and Lusch named this way of looking at the world a goods-dominant logic.

It is this thinking that leads us to a value-in-exchange view of value. And we have to acknowledge that value-in-exchange has been wildly successful model over the last few centuries. It has challenges, though, in the form of blind spots, which are increasingly becoming obvious as our growth stalls and innovation/sales becomes harder.

Vargo and Lusch challenge these 5Is of service assumptions in “The Four Service Marketing Myths“, arguing that the traditional distinctions between goods and services are misleading. Here’s what they say (with my annotations in square brackets):

Vargo & Lush (2004) “The Four Service Marketing Myths“ with notes

- Unless tangibility has a marketing advantage; it should be reduced or eliminated if possible [enabling rapid scalability, think Spotify versus CDs]

- the normative marketing goal should be customization rather than standardization [enabling greater progress to individual seeker’s progress sought from their progress origin = resulting in greater value emerging]

- the normative marketing goal should be to maximize customer involvement in value creation [enabling greater alignment to individual progress sought from progress origin = greater value emerging through co-progress making (may be called value creation in the literature]

- the normative goal of the enterprise should be to reduce inventory and maximise service flows [why tie up cash through storing multiple units that don’t align with individual progress journeys?]

The alternative view is to look at service as a processes rather than output.

Service (sigular) ✅

Instead of viewing services as a unit of output, we shift our focus to the process of service itself. Vargo & Lusch emphasise this distinction by using “service” in the singular, defining it as:

the application of competences (knowledge and skills) for the benefit of another party

Vargo & Lusch (2008) “From Goods to Service(s): Divergences and Convergences of Logics”

This reframing has three key implications, it:

- directs attention to understanding and developing competences rather than merely categorising outputs

- dissolves the traditional goods-versus-services debate by recognising that goods are simply a means of transporting service (knowledge and skills)

- opens the door to thinking in terms of effort expended in applying those competences (which is key to understanding price in the progress economy)

However, this definition requires some refinement to reflect the progress economy. Firstly, not all service benefits another party – self-service exists. Moreover, service is not limited to applying competences (knowledge and skills); other capabilities, such as physical attributes (eg strength), natural forces (eg movement from wind or waterflow), and abstract elements (eg time), can also be involved.

In The Progress Economy, we adopt a broader definition:

service (singular): the application of capabilities* to help oneself, or more often, another party to make progress

Based on Vargo & Lush (2008) “From Goods to Service(s): Divergences and Convergences of Logics”

* knowledge and skills, as well as physical such as strength, natural such as movement of wind, or abstract such as time

To complete the picture, capabilities are carried by resources; and progress is made through acts of resource integration (effectively applying capabilities).

Types of service

There are various ways of categorising service.

One particularly useful way, in the progress economy, is to consider who applies capabilities (integrates resources). Sometimes the Seeker performs the work themselves, as a form of self-service. Sometimes the Helper takes on the effort entirely. Most often, it’s a blend of both.

It could be the “self”, as in a form of self service; or it could by completely the service provider; or a combination. This leads us to observe there is a continuum of progress propositions/service, ranging between enabling and relieving propositions. We call that the progress proposition continuum. A proposition’s position on that continuum is driven by who performs the majority of the progress-making activities. And sliding a proposition along it is a powerful lever for innovation.

We can also categorise service by leveraging Lovelock & Wirtz’s four types of service processing (from ”Services Marketing”) to further understand service (and the types of functional progress Seekers are looking to make). They categorise service as:

- people processing – make progress on a human body (eg healthcare, hair cutting, fitness, nutrition)

- possessions processing – make progress with possessions (eg repair, storing, transporting)

- mental-stimulus processing – make progress with (eg education, gaming, entertainment)

- information processing – make progress that involves manipulating information/data (eg banking, IT services)

It’s a useful categorisation for when we want to hunt particular functional progress to address.

With this understanding of service (singular) in our minds, it is time to consider service exchange.

Exchanging Service – engine of economic activity

Let’s boldly say that Service (singular) exchange, rather than value exchange, is the true engine of economic activity. Service-dominant logic, which sits in our foundation layer, states this directly:

Service is the fundamental basis of exchange

#1

At first you might disagree – after all, your living experience usually sees you handing over hard earned cash for products. But this is, I claim, an illusion that hides service exchange as the truth.

The progress economy tells us why this is so:

- every actor in the economy is seeking to make progress to their own more desirable state

- the distribution of capabilities needed to make all that progress is uneven.

This combination of universal progress-seeking and unbalanced capability drives actors to exchange service (remember, this is the application of capabilities to help themselves or, more often, others to make progress). In essence: I do something for you, and I expect you to do something for me. This we’ll call direct exchange, and we’ll need the concept of service credits – promises of future service – to mediate temporal and magnitude differences. This provides a practical basis for understanding price away from a signal of value.

Note that we should not mistake this for a barter economy, where goods or services are traded directly and individually without a cash or cash equivalent being used. The dynamic at play is more structured and scalable.

From here, we can see, as service-dominant logic observes, that various types of indirect exchange mask the underlying reality of service-for-service trade. These are transitive, distributable, internal, and network indirect exchange. It is indirect exchange and service credits that provide the illusion of value-in-exchange. That has been wildly successful for centuries, but has blind-spots that we are increasingly hitting.

It is time to rediscover service as the true nature of exchange. It isn’t just clarifying, as I’ve mentioned, it’s a fundamental lever for innovation.

To get the story going, we’ll first look at direct exchange.

Editing below here

Direct exchange

Direct service exchange is a straightforward concept: you help me make some progress, and in return, I help you with some progress you are seeking.

Such a direct exchange relies on individuals having capabilities to swap and them finding each other to engage in this exchange. For example friends helping each other move house, participating in getting rounds of drinks during nights out, or doing favours for others.

Direct exchange also exists in the commercial world.

In particular actors in platforms have direct exchange. Each applying its capabilities to help the other make progress. Apple’s success in the iPhone era rests on a direct, reciprocal exchange with developers. Apple offers tools, APIs, billing systems, platform stability, and global visibility. Developers provide the functionality, innovation, and niche expertise that make the platform compelling and differentiated.

Salesforce and its global consulting partners form another clear example. Salesforce provides the technical platform, brand, and market demand; partners supply the domain expertise, customisation, and integration skills that make the platform usable in real organisational contexts.

In both cases there is also an exchange with end customers – the seeker “buying” an app, or the business purchasing Salesforce licenses – that is an indirect exchange we’ll come to momentarily.

Frist, direct exchange allows us to simply explore to traits of exchange. The exchange might be separated in time and the efforts involved might have different magnitude.

Tracking temporal differences: Service credits as IOUs

There’s often a temporal gap in an exchange. By that I mean I might help you move this weekend, but you might not need my help for months.

To mediate these temporal differences, we need a tracking system – a register of service IOUs. We’ll call these “service credits“. They are promises of future service. When I provide a service to you, you give me a service credit that I can redeem (with you) at a later point in time.

These service credits can take various forms, from a mental note among friends to a formal contract, entries on a central or distributed register/ledger, to tokens/IOU notes you carry with you. The formality of such service credit implementation increases with the level of unfamiliarity or trust required between the parties involved.

Aligning magnitude differences

Simplistically, one unit of service could be represented by one service credit.

But, outside of an altruistic society, that breaks down due to views of unfairness. Does you cooking me a meal (or rather you applying your culinary skills for my benefit) equate to me helping you move a 5-bedroom house?

To answer that, we need to introduce the concept of equitable service exchange. Both parties need to agree that the effort they are swapping is equitable (fair). It doesn’t have to be equal, just fair.

So it certainly could be the case that we both feel you cooking me a meal in exchange for me helping you move is sufficient. It’s clearly not equal; but if everyone involved feels it is equitable, great. Or we could agree that you cooking me 4 meals is equitable, or 2 meals, or some not yet defined future help.

As with temporal differences, we can mediate magnitude differences through service credits. Now we associate a number of service credits with each service being exchanged.

And here we begin to get a glimpse into what price means in the progress economy.

Service Effort – The basis of price

Lastly, let’s look at price. In traditional economic thinking, price and value collapse into one another: value is defined as the maximum price a customer will pay. Once we move beyond value-in-exchange, that equivalence disappears. Yet price remains very real and very consequential.

In the progress economy, price serves a different role. It signals the level of effort a Helper expects in return for the effort they will invest in helping a Progress Seeker make progress

price: the effort* a Helper expects to get from a service exchange

* this may be through direct, indirect service, or service credits

Importantly, the return need not occur in a single moment. It can unfold over time:

and if effort is usually thought of in terms of service credits, we could equally write:

In other words, price represents both the amount of effort – or number of service credits – and the frequency of exchange that the Helper proposes as an equitable exchange for the effort in service they will provide.

Setting price is a topic in its own right, which we will address later. It includes profit: the additional service credits a Helper requires beyond a pure reflection of the effort embedded in the proposition.

Ultimately, the Progress Seeker decides whether the exchange feels equitable – or, more precisely, whether the inequitable exchange progress hurdle is sufficiently low enough. That judgment is usually made alongside an assessment of progress potential and the heights of the other five progress hurdles, shaping what the Seeker interprets as potential value.

A note on service credits and psychology

Our treatment of service credits is sufficient for the purpose at hand, but it is not complete. For service credits to function at scale, they must possess additional attributes such as durability, divisibility, fungibility, scarcity, and the ability to retain strength over time. For now, however, a lighter view is enough.

Cash is a highly successful implementation of this mechanism, just as shells and rocks have been in the past. As money becomes more digital, it moves even closer to the idea of service credits, Living in Sweden, I can’t remember the last time I saw or used physical cash, it’s all just numbers on my mobile app that increase when I get my salary and decrease, through blipping my phone on a reader, when I get service. Do digital currencies like BitCoin work as service credits? Partially, but they may lack certain requirements like stability.

At our current level, service credits expose a simple psychological reality: I must give help, to get help. The effort I put in (effort multiplied by instances) I need to feel is reciprocated in a way that feels equitable. Price, in this frame, signals the amount of effort I need to commit in order to access a specific form of help.

Seen this way, the appeal of buy-now-pay-later, credit, loans, and business models such as subscriptions or subsidies becomes clear. They reduce the effort I must exert today to secure the help I need now.

With this foundation of direct exchange in place, we can acknowledge indirect exchange.

Let’s progress together through discussion…