The value model underlying service-dominant logic, which sees value as increased well-being and promises to address value-in-exchange’s blind spots; but it needs a further evolution to become the actionable powerhouse fixing our sales, innovation and growth problems.

What we’re thinking

The value-in-use model evolves our view of value away from it being an output, embedded-exchanged-used up, to it being co-created during a process, resulting in an increase in well-being.

It’s grounded on three simple concepts.

- “value really emerges for customers when goods and services do something for them. Before this happens, only potential value exists”

- Everything is a service – “the application of competence (skills and knowledge) for the benefit of another”

- Value is phenomenologically judged – that is, based on past and current experience – by the beneficiary, not the provider

Welcome to the service-dominant world of resource integrations, relational approach, and co-creating value to increase well-being.

Why this matters

By removing the focus on a point of exchange, and introducing service-dominant thinking, the value-in-use model offers a clear path to address the growth-limiting blind spots we’ve identified with our traditional value-in-exchange model.

However, to get an actionable model solving our innovation, sales, and growth problems, we need to better understand what well-being is and find the levers to improve it. For that, we need to introduce progress, and evolve to the well-being-through-progress model.

Editing below here

Key concept: Value comes only through using resources

Our journey Into value-in-use starts with the insightful observation from Grönroos:

It is of course only logical to assume that the value really emerges for customers when goods and services do something for them. Before this happens, only potential value exists

Grönroos (2004) “Adopting a service logic for marketing”

Whereas the traditional value-in-exchange model sees value as embedded into products by manufacturers, Grönroos’ insight indicates that value emerges only when goods and services are used by customers. Products have no embedded value, only potential value that may be realised when using them.

For instance, a drill only creates value as it is used to make a hole. When sitting on the shelf doing nothing, it is creating no value; it has only the potential to create value. Similarly a call-centre is only creating value when handling a customer call. When there are no calls, it has only potential.

This perspective, as we’ll see, has a profound impact on how we see value and therefore innovation.

benefits

- focussing on true determinator of value

- seeing opportunities before, after, and across the point of exchange

- harnessing the circular economy

- leveraging the sharing economy

- freeing us from the the constraining IHIP/5Is view of services

- enabling or relieving the beneficiary, or somewhere in-between

- seeing a wider solution space

- seeing a system of propositions

- seeing a wider business model space

constraints

- defining value (well-being) remains challenging

- lacking clear mechanisms for value creation

- constraining definition of service

- only the beneficiary determines value

- lose actionable definition of price

- moving to direct service is all consuming

One key thing to notice is our shift from viewing value as being embedded in outputs to it emerging through the process of arriving at that output. Welcome to the world of service-forward logics.

What are service-forward logics?

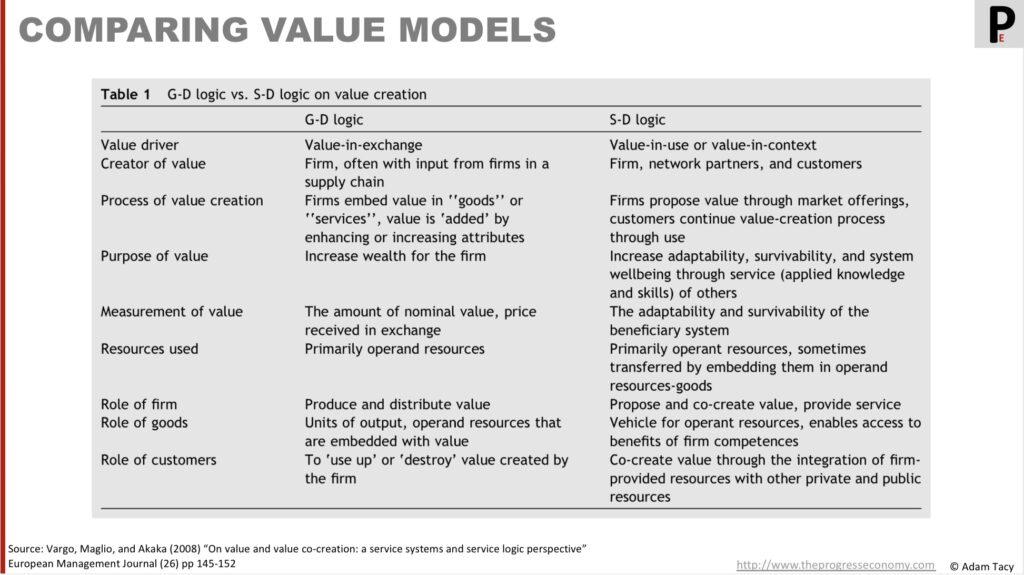

As we’ve explored, traditionally we view the world as one where goods are paramount, services are secondary, and value is seen primarily through value-in-exchange – the greatest amount you can get for your product. Vargo and Lusch term this goods-dominant logic due to the dominant role of goods in the thinking.

Wouldn’t it be interesting to instead explore a world where service is the dominant concept and see the implications? Now we would start with defining service and position goods in terms of that. We‘ll find value gets reframed as being (co-)created through the use of competence provided in a service (propositions).

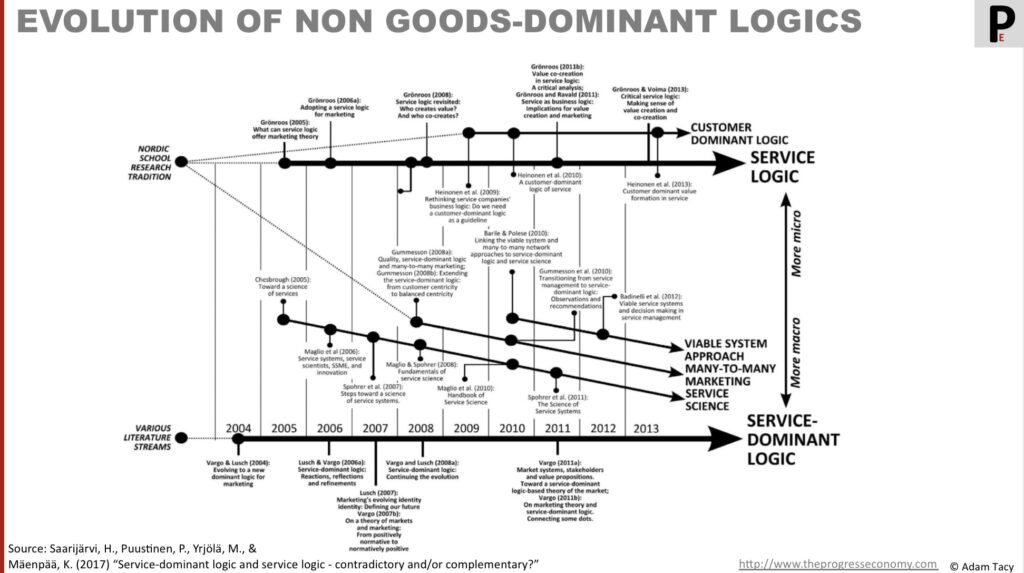

Two main service-forward logics have emerged from following that simple thought: Grönroos’s service logic and Vargo and Lusch’s service-dominant logic.

Both logics start with service and define value as created in use. The primary distinction between them is that service logic is more micro-focused, while service-dominant logic takes a macro perspective (Saarijärvi, et al (2017) “Service-Dominant Logic and Service Logic – Contradictory and/or Complementary?”). Luckily, at our level of exploration, this distinction need not concern us.

The progress economy is built on Vargo and Lusch’s service-dominant logic, with inspiration from Grönroos as necessary. This choice is driven by practicality and circumstance – service-dominant logic was the first non-goods-dominant logic I encountered, it answered my initial questions, and it is neatly explained through 11 foundational premises.

It’s worth noting that both logics come from the marketing field and we’re now looking to leverage them to improve innovation. We should therefore expect some “deficiencies”. Those we will address with value-in-progress.

Before exploring service-dominant logic further, we should first look at what we mean by service.

defining service

The first thing to note is we use service in the singular. We do that as “a perspective on value creation rather than the product category of ‘services’ (plural)” (Edvardsson, Gustafsson and Roos. (2005) “Service portraits in service research: a critical review”).

What does this mean? Simply that we define service as Vargo & Lusch do:

service is the application of competence (skills and knowledge) for the benefit of another entity or the entity itself

Vargo & Lusch (2004), “Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing”, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 68, pp. 1-17

That’s a contrast to our traditional approach where we talk of services (and goods), in the plural, as product categories. Where the services product category is defined in relation to the goods product category, usually as a poor relative.

Now we define service (singular) as applying skills and knowledge to benefit an actor. Where that actor is often someone else but it can be yourself (self-service).

With this in mind, let’s look at service-dominant logic before we see how goods fit into this thinking.

introducing service-dominant logic

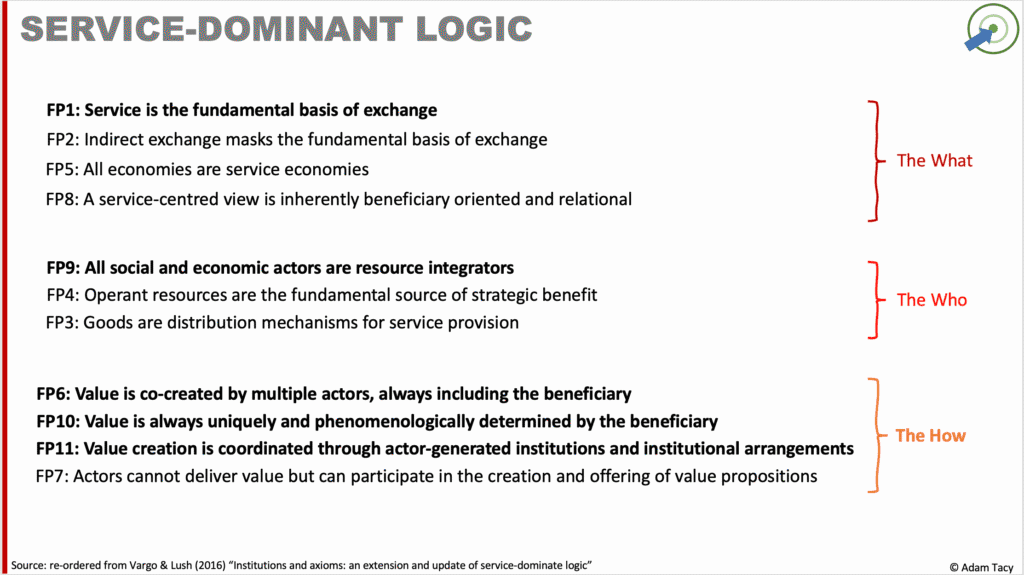

Here are those 11 foundational premises previously mentioned. Five of which are considered axiomatic (in bold) i.e. the others can be derived from them (see papers from 2004, 2008 and 2016). I’ve also grouped them into three blocks: the what, the who, and the how.

Let’s quickly touch on the first four axioms (you can dig deeper into service-dominant logic here if you wish).

Firstly, service is the fundamental basis of exchange (FP1). This immediately distinguishes us from the traditional value-in-exchange model where that basis is value (leading to price as a measure of value). Essentially, I apply my competence (skills and knowledge) to benefit you, and you apply yours to benefit me.

This doesn’t imply two-party bartering for outputs in a fictional medieval fashion.

You may already be thinking that you are rarely involved in such exchange just described. The logic recognises that service exchanges are often indirect, masking them as the basis of exchange (FP2). Examples of indirect exchange are transitive, intra-organisational, or through goods.

The most obvious is transitive indirect exchange. For instance, when you work for an employer you are providing service, applying your skills and knowledge. But you most likely engage service from elsewhere such as watching a film, enjoying a meal etc. this is transitive exchange in action.

Service-dominant logic is unfortunately silent on the mechanisms enabling indirect exchange; in the progress economy we will see this as mediated by service credits (of which money has been a very successful implementation).

Another observation about service exchange is its relational nature (FP8). It is the dialog during exchange rather than transaction of outputs that is of importance in increasing value – as exemplified in the difference between getting a bespoke suit versus an off-the-shelf one.

Resource integration is another key concept that “all social and economic actors are resource integrators” (FP9). Looping back to our making a hole example; that is achieved by you (a resource) correctly integrating with the drill (another resource). It could equally be you integrating with a handyman (a different type of resource) explaining where you want a hole, and the handyman making the hole.

It is natural, then, to see value as being co-created by multiple actors. And that one of those actors is always the beneficiary (FP6). Although it might be one of the actors provides their competence frozen in the form of a goods (a hint here of the role of goods we will shortly look at).

Grönroos would argue that Vargo & Lusch have stepped too far here with a philosophical debate on value co-creation requiring multiple actors; a beneficiary can create value on their own – you might transport fruit in a wicker basket you made from reed you collected.

Finally, value is uniquely and phenomenologically determined by the beneficiary (FP10). This means beneficiaries alone determine value (not manufacturers), and each beneficiary’s determination may be different. It is their past and current experiences (phenomenon) that drive their judgements.

This is behind why you might find a supermarket self-checkout useful at a rushed lunchtime with just two items but not during your weekly shop (or why your friend might enjoy using them with her children during the weekly shop as the children enjoy helping; while another friend avoids them due to the risk of accidental theft being pushed on to them). I have more on what phenomenological means here, we’ll use it a lot in the progress economy.

I’ll draw inspiration from both service-dominant logic and service-logic as we explore value-in-use.

One thing we should loop back to is how we will look at goods.

exploring the “new” role of goods

Now we get to an interesting view. Here’s how we look on goods in a service-forward way of thinking:

Goods are distribution mechanisms for service provision

#3

They allow us to distribute service provision in time and space. Conceptually, they freeze service provision which is then unfrozen, when and where needed, through acts of resource integration.

At first this probably sounds odd! Think of it this way: you want to listen to some music, how could you do that?. You could attend a live concert by your favourite band. Alternatively, you could listen to the same band on vinyl, CD, or via a digital stream.

The first alternative clearly meets our definition of a service – the band are using their skills and competence to entertain (benefit) you. In the second alternative, the band’s service provision has been frozen into a recording and is unfrozen when you press play on your device. It has also been distributed to when and where you hit that play button (physically through a supply chain and by yourself in case of vinyl/CD and digitally over the air in the case of a stream).

The choice between live or recorded music becomes a matter of beneficiary preference – what is valuable to them (in the context they are in).

With this positioning of goods we remove the constraining goods vs. services debate; the conversation shifts to how the beneficiary prefers to engage a service. This thinking can be hard to do in a value-in-exchange model. Just recall the struggle the music industry had with streaming services.

This shift has several implications. Service frozen into goods tend to be:

- found more in enabling propositions – those where the beneficiary performs a lot of the service activities – and less in relieving propositions

- quite specific in scope, potentially requiring beneficiaries to chain multiple goods together to get what they want

- not always a one-one replacement for a more direct service (see above)

- dependent on greater beneficiary competence (understanding how to use them, etc.)

This way of thinking opens the door to a reduction in Levitt’s “Marketing Myopia”.

The great Harvard marketing professor Theodore Levitt used to tell his students, “People don’t want to buy a quarter-inch drill. They want a quarter-inch hole!”

Christensen, C. M., Cook, S., Hall, T. (2005) “Marketing Malpractice” Harvard Business Review

Ok, with this background in our bag, let’s turn our attention to the value-in-use value model.

Value-in-use

Following Grönroos’ observation that “value really emerges for customers when goods and services do something for them”, we uncover the value-in-use model of value.

value-in-use: A view of value creation that sees value being co-created through service (offered as value propositions) to improve a beneficiary’s well-being.

As you can imagine, we look at value differently in this model. Vargo, Maglio & Akaka (“On value and value co-creation: A service systems and service logic perspective”, European Management Journal (2008) 26, 145–152), compare value in goods- and service-dominant logic. They tell us the purpose of value is to enhance system well-being, adaptability, and survivability, through service of others.

So let’s explore how value is defined, measured, created, and destroyed in this model. Along the way we’ll see how the value-in-exchange growth blindspots are addressed. Though we’ll find that we essentially replace a challenge of defining value with a challenge of defining well-being. Well-being is marginally better than value, but falls short of providing the actionable definition of value we need for more systematic innovation.

defining value – an increase in beneficiary/system well-being

Unfortunately (or fortunately), we can no longer define value as the “maximum a customer is willing to pay,” as McKinsey did for the value-in-exchange model, since we no longer have value exchange. This also has implications about the meaning of price, something we will revisit later. So, what could value relate to?

Our first insight comes from previous quotes by Grönroos – “goods and services do something” – and Vargo & Lusch – “benefit of another entity or the entity itself”. Through these, we see that value becomes tied to a change for the customer (or beneficiary, to use the language of service-dominant logic).

Grönroos‘ perspective is that value means customers feel “better off than before”:

Value for customers means that after they have been assisted by a self-service process (cooking a meal or withdrawing cash from an ATM) or a full-service process (eating out at a restaurant or withdrawing cash over the counter in a bank) they are or feel better off than before.

Grönroos, C. (2008) ”Service logic revisited: who creates value? And who co-creates?”;

European Business Review 20(4):298-314

We will interpret this “better off than before” as an increase in the beneficiary’s well-being. This should, in turn, enhance the system’s well-being, adaptability, and survivability, as noted by Vargo, Maglio, and Akaka (since the system includes the beneficiary and any firm(s) offering proposition(s) that are used).

Value, then, can be defined as:

value: an increase in the beneficiary’s well-being

This is a better definition of value compared to the “highest price someone is prepared to pay” of the value-in-exchange model. It shifts the focus from manufacturer to the beneficiary and embodies the principle that value comes from use. It also implies the need to understand what that increase is to a beneficiary.

Reflecting a discussion we will have later on value co-destruction, it has been suggested that value is a positive or negative change in a system’s well-being:

value – an emergent change in the well-being or viability of a particular system/ actor, which can be positively or negatively valanced

Vargo, Peters, Kjellberg, Koskela-Huotari (2022) ”Emergence in marketing: an institutional and ecosystem framework”; Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 51(4)

However, defining value as an increase in well-being (or even positively or negatively valanced) remains a vague concept. What is well-being? How is it measured?

measuring value

Flowing directly from our definition above, we can measure value as the change in a beneficiary’s well-being from service (the application of competence (skills and knowledge):

Which, according to service-dominant logic, is something the beneficiary always measures (determines):

value is always uniquely and phenomenologically determined by the beneficiary

#10

Grönroos also notes that “before [goods and services do something], only potential value exists”. This suggests that beneficiaries determine value at least twice:

- value that may arise from using a particular proposition – potential value

- value that has arisen from using that proposition – actual value

The literature doesn’t go into this, nor whether these are one-off or more continuous determinations.

For a beneficiary to measure value – the potential or actual change in well-being – they need to measure well-being. How do we do that?! Well, some aspects of well-being are more directly measurable whilst others are more subjective.

For example, the improved well-being of moving location can be measured in metres, kilometres, or miles. Whereas improving language competence can be measured using artificial scales, such as the A1 to C2 levels of the Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR). Other forms of well-being, such as hapiness, require more subjective scales.

The take-away is that we have a better measure of value by looking at it as a measure of well-being than as price. Yet well-being is still fuzzy to define and reason with.

Like we did for value-in-exchange, let’s see how value is created and destroyed to see if that provides more insights into defining value.

co-creating value

Remember in the value-in-exchange model, value creation was seen as manufacturers successively embedding additional value in products through the supply chain, resulting in a product that held value ready for exchange?

Now we have a very different model of value creation. There is no value embedded in products; rather, actors propose how value can be created. Vargo & Lusch codify this as foundational premise (FP7):

Actors cannot deliver value but can participate in the creation and offering of value propositions

#7

These value propositions offer to apply competence (knowledge and skills) for the benefit of the beneficiary (i.e., what Vargo & Lusch defined as service). These competences may be directly applied, such as through employees of a firm, or frozen into goods for the beneficiary to apply themselves, or some combination thereof.

A handyman, for instance, offers their competence to help you hang a picture frame; or a drill freezes a manufacturer’s competence in making holes, which you can then use as part of the process of hanging that picture frame yourself.

Beneficiaries choose to engage with propositions they feel best enable them to increase their well-being.

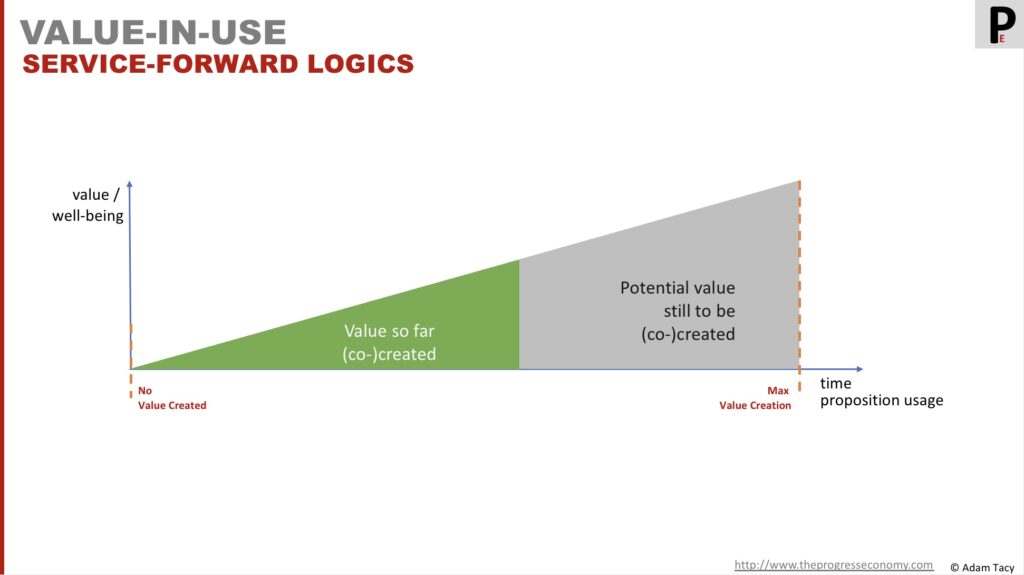

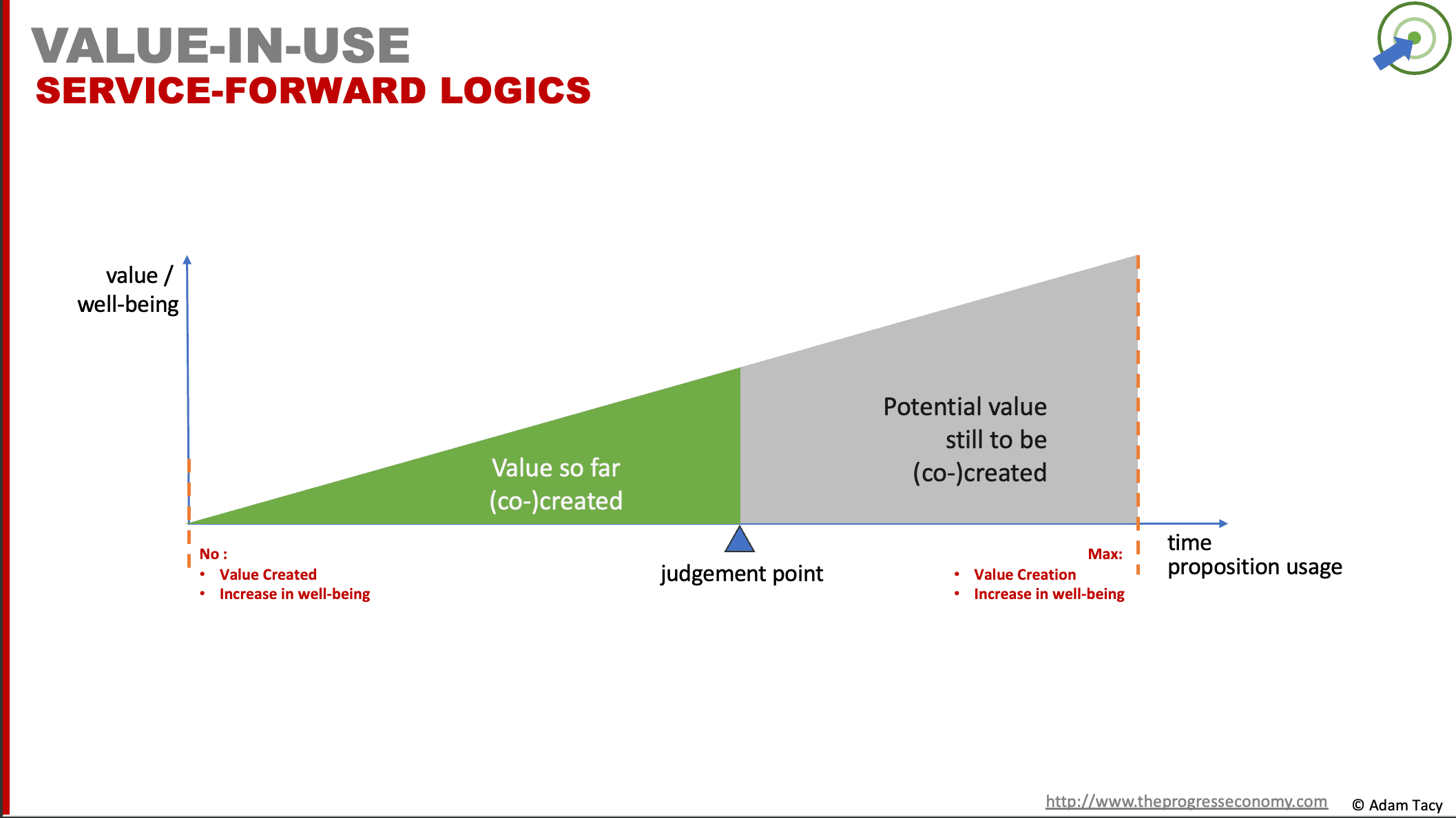

Here’s how we can visualise value creation.

What we’re seeing is that there is no value created (no increase in well-being) until a proposition is used. As we use propositions, well-being increases and, therefore, so does value. We can assume that maximum value is created when the beneficiary reaches their intended increase in well-being.

The process of increasing well-being is one of resource integration. Those resources are ones owned by the beneficiary and those offered in the value proposition. For example, you integrate your competence (knowledge and skills) of driving a vehicle with a car manufacturer’s competence of safe mechanical propulsion they have frozen into a goods – the car – to increase your well-being relating to moving distances.

Since both the beneficiary and firm(s) offering proposition(s) have resources that integrate to increase the well-being of the beneficiary, we refer to the process as value co-creation.

value is co-created by multiple actors, always including the beneficiary

#6

Interestingly, service-dominant logic advocates that all value creation should be considered co-creation, whereas service logic argues that co-creation only occurs when firms offer resources capable of dialogue. (Grönroos (2008) “Service Logic Revisited: Who Creates Value? And Who Co-creates?”). So the handyman above can co-create value but not the drill (until it perhaps becomes AI dialogue enabled). We’ll steer away from this debate for now, as we’re using value-in-use as a stepping stone model.

Who performs these integrations also introduces a distinction in the type of proposition. In fact, a firm “must decide where on a continuum of ‘enabling’ to ‘relieving’ service it will be” (Bettencourt, Lusch, and Vargo. (2014) “A service lens on value creation”). We’ll see this continuum again in our value-through-progress model – it is more powerful than it appears at this point.

As a final point, multiple propositions may need to be linked to achieve the desired increase in well-being. Consider online shopping: website hosting, product fulfillment, delivery, customer service, and payment processing must all work together with the beneficiary. We can see this as a service system.

service system, a configuration of people, technologies, and other resources that interact with other service systems to create mutual value.

Maglio, Vargo, Caswell, Spohrer (2009) ”The Service System Is the Basic Abstraction of Service Science”; Inf Syst E-Bus Managent 7:395–406

Coordination of the system can be managed in various ways. Often, one actor coordinates as part of the overall value proposition. In other scenarios, the beneficiary is given choices, such as different payment processors (Visa, direct bank transfer, deferred payments through Klarna,…) or alternative delivery providers. In some cases, the beneficiary must coordinate the propositions themselves.

Just like with value-in-exchange, we can destroy value, however the concept and timeline is different.

destroying value

In our new model, destroying value is not about using up value embedded in products by manufacturers. Instead, it is the act of hindering the increase in well-being that a beneficiary is striving to achieve.

Can value, just as it is co-created, be co-destroyed? Plé and Cácares encapsulate this concept as follows:

value co-destruction…interactions between actors result in a decline in at least one of the actors’ well-being.

Plé and Cácares (2010) “Not always co-creation: introducing interactional co-destruction of value in service-dominant logic”

There are numerous instances and ways this decline, or more accurately, failure to increase as expected, may occur.

For example, imagine you are trying to create a hole in your concrete wall to hang a picture but don’t realise you need a drill with hammer action. Your well-being does not increase (value is destroyed), and you might blame the drill manufacturer. Or if you hire a handyman to hang the picture and it goes in the “wrong” place. Was the handyman poor; were you unable to explain where you wanted the picture?

Your disappointment might see you writing a scathing online review in an attempt to recover some value. Now you might be destroying value for the manufacturer/handyman if your review dissuades others from using their product.

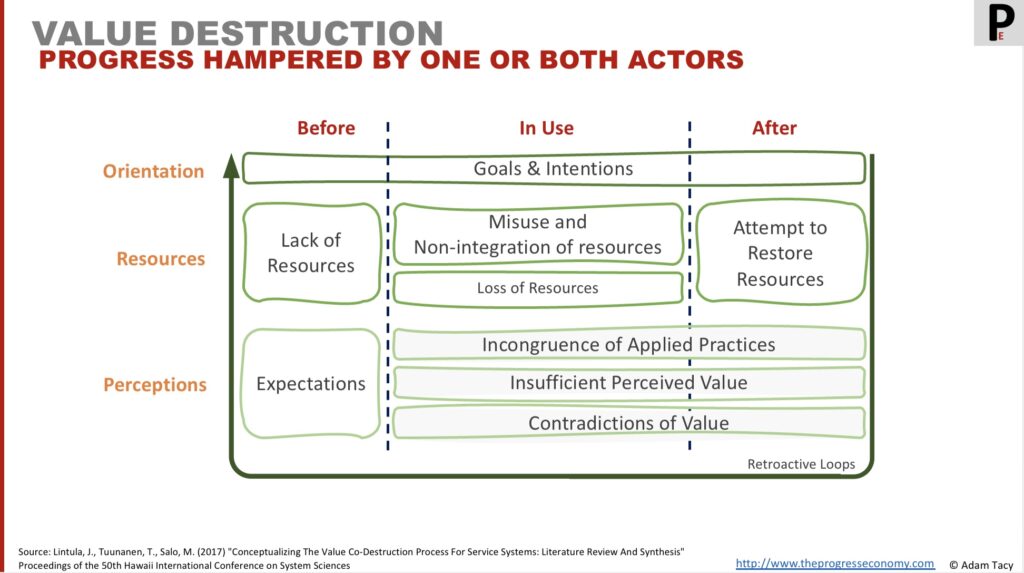

Lintula, Tuunanen, and Salo provide a useful framework for understanding the causes of value co-destruction (“Conceptualizing the Value Co-Destruction Process for Service Systems: Literature Review and Synthesis”).

Their framework examines where value co-destruction can occur: before, during, and after service. It also considers what may be involved: orientations, resources, and perceptions.

It’s a powerful framework to review propositions against before offering and for reviewing them regularly.

However, this is a problem talking about the “co” part in co-destruction. Looking at Lintula framework we can reason that, it doesn’t take more than one party to destroy value. If the beneficiary misuses resource, for example, then value may be destroyed. It doesn’t require any other actor to participate in the destruction. Alexander & Vallström have the same thought, expressed in more detail, in their 2023 paper “Value co-destruction: Problems and solution”.

It’s for this reason I do not include the “co” prefix when discussing value destruction.

value-in-context – context is important

An important aspect we haven’t discussed yet is context – the circumstances under which a beneficiary seeks to increase their well-being and which other actors provide resources to help. Context significantly influences a beneficiary’s decisions.

Are they pressed for time? A relieving proposition may be more appealing. Are they traveling? Different options will be attractive depending on whether they are traveling during rush hour or off-peak hours, or whether they possess a driver’s license.

For this reason, value-in-use is sometimes defined and used in relation to context. In these cases it is referred to as value-in-context.

So, we’ve now defined, measured, (co-)created, and considered the destruction of value within the value-in-use model. It signifies an increase in well-being for the beneficiary and ideally for the entire system. Now, let’s explore the model’s advantages over value-in-exchange and its limitations.

The model’s benefits

The emphasis on dialogue, relationships, and view on value creation (-in-use) has the potential to minimise, and even remove, the blind spots inherent in the value-in-exchange model. We end up:

- focussing on true determinator of value

- seeing opportunities before, after, and across the point of exchange

- harnessing the circular economy

- leveraging the sharing economy

- freeing us from the the constraining IHIP/5Is view of services

- enabling or relieving the beneficiary, or somewhere in-between

- seeing a wider solution space

- seeing a system of propositions

- seeing a wider business model space

Let’s take a deeper look at these.

focussing on true determinator of value

I’m sure you’ve picked up by now that we change who determines value.

Back when we exchanged value it was the manufacturer, now i) actors can only offer value propositions (FP7), ii) value is co-created (FP6), and iii) only the beneficiary determines value (uniquely and phenomenologically) (FP10).

Practically, this means that actors offering propositions must be more externally focused. They need to understand the improvements in well-being that beneficiaries seek to achieve. This enhances the likelihood of improved innovation and value.

Adopting a service view, as service-dominant logic indicates, is inherently beneficiary-focused and relational (FP8).

seeing more opportunities by removing point of exchange

Removing the point of exchange means, as Ballantyne & Varney put it, “the time logic of marketing exchange becomes open-ended”.

the time logic of marketing exchange becomes open-ended, from pre-sale service interaction to post-sale value-in-use, with the prospect of continuing further, as relationships evolve

Ballantyne and Varey (2006) “Creating Value-in-use Through Marketing Interaction: The Exchange Logic of Relating, Communicating and Knowing”, Marketing Theory Vol. 6, No. 3(3)

There is opportunity for interaction before the service, during the service, and after the service. The levels of interaction vary and may be distributed across several actors and propositions.

While I’m not suggesting a revolution in the process of selling a nail, we should aim to customise our offerings and involve the beneficiary as much as makes sense from their perspective. Vargo & Lusch advocate for this in “The Four Service Marketing Myths“:

the normative marketing goal should be:

Vargo, S., Lush, R. (2004) “The Four Service Marketing Myths”; Journal of Service Research; Vol 6; Issue 4; pp 324-335

- customisation rather than standardisation

- to maximise customer involvement in the creation of value

The more we can customise and involve the customer before and during service, the greater the chance we help them achieve exactly what they uniquely and phenomenologically seek.

Once the service provision is over, it is beneficial to follow up with the beneficiary to continue finding ways of co-creating more value.

Finally, remember Lintula’s framework for value co-destruction from earlier? It provides the rails for value proposition providers to minimise value co-destruction before, during, and after service provision.

Harnessing the circular economy

With its more open ended time logic, the value-in-use model is the notion of value the Ellen MacArthur foundation are calling for:

one of the biggest challenges…to transition from linear to circular is that it requires…revisiting the very notion of value creation

Ellen MacArthur Foundation (2023) “From ambition to action: an adaptive strategy for circular design”

We saw value-in-exchange, with its focus on embed-exchange-use basis and maximising exchanges, is the poster child for the linear economy’s take-make-waste approach.

In contrast, value-in-use thinking promotes a more holistic view of well-being. If beneficiaries seek to engage in the circular economy – for example through repurposing, repairing, reselling, etc. – we should identify and facilitate that. This can be achieved by offering these services ourselves or by designing products that allow others to offer them.

However, herein lies an insight into the ugly challenge for the circular economy. Innovation (new offerings) should increase the well-being of the system as a whole. If there are insufficient beneficiaries willing to support a circular economy proposition, then the well-being of the system risks becoming compromised. In plain terms, if there’s not the demand, it is likely uneconomical (from value proposition providers’ survivability perspective).

leveraging the sharing economy

When we recognise that propositions only create value when being used, we notice a lot of inefficient resource usage. That drill you use for making holes is not used that often. That is a lot of potential value just sitting there.

How can we unlock that potential value sitting on our shelves? We can leverage the sharing economy.

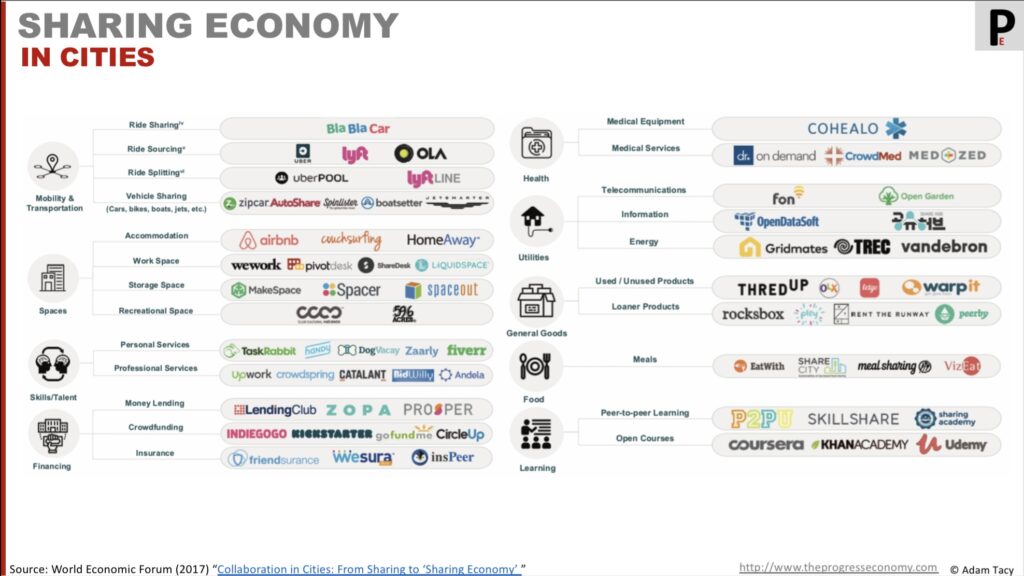

Sharing economy: focus on the sharing of underutilised assets, monetised or not, in ways that improve efficiency, sustainability and community

Rinne, A. (2017) “What exactly is the sharing economy?” World Economic Forum

And there are many platforms to share resources. Here’s a few examples from a World Economic Forum White Paper entitled “Collaboration in Cities: From Sharing to ‘Sharing Economy’”.

There’s nothing spectacularly new about today’s sharing economy, except perhaps the ease of access and variety of resources available. Businesses have been doing this, in waves, for years.

Back in the day housewives used to cook in the residual heat of the local bakers ovens. Computing in the ‘60s used to be loaned out, before prices dropped sufficiently and demand increased to have your own hardware. A trend that is now in the cycle of companies leveraging cloud computing.

What drives this wider variety is a growing appreciation of increasing efficiency of resources (made more obvious by value-in-use thinking).

freeing us from the constraining IHIP/5Is view of services

We saw earlier that Vargo and Lusch argue in “The Four Service Marketing Myths” that we should see inconsistency of the IHIP/5Is description of services as the more positive customisation.

They also argue that the other traditionally negative attributes of services should be seen positively:

Vargo and Lusch (2004) “The Four Service Marketing Myths”; Journal of Service Research 6(4):324

- intangibility => unless tangibility has a marketing advantage, it should be reduced or eliminated if possible

- inconsistency => the normative marketing goal should be customization, rather than standardization

- inseparability / involvement => the normative marketing goal should be to maximize consumer involvement in value creation

- inventory => the normative goal of the enterprise should be to reduce inventory and maximize service flow

These are all things to consider in evolving your offerings to a value-in-use thinking.

When we do offer goods, it is to distribute service. We have set aside the old goods vs. services debate, focusing instead on what best suits the beneficiary. This can be through direct service or indirectly through goods, leading us to a continuum of value propositions.

enabling or relieving a beneficiary, or somewhere in-between

We can provide service directly through, for example, employees or indirectly through goods (Vargo & Lush in “Why service?”). This distinction leads to an interesting characteristic: service can be enabling or relieving.

Norman’s “Reframing business: when the map changes the landscape” introduces these concepts. To quote from “Why service?”:

Norman’s distinction is essentially based on which party’s operant resources are most central to value creation. In relieving processes, the firm is using its operant resources to provide relatively direct service for the consumer and in enabling processes, the customer is primarily using relatively more of his or her operant resources to act upon resources provided by the firm

Vargo & Lush (2008) “Why service?”

The distinction is based on whose operant resources are most central. Operant resources act on other resources to create value (while the other type of resource, operand, need acting upon to create value.

In fact, there is a continuum between these two points of enabling and relieving service. According to Bettencourt, Lusch, and Vargo. (2014), a firm “must decide where on a continuum of ‘enabling’ to ‘relieving’ service it will be” (“A service lens on value creation”).

We’ll see this continuum again in our value-through-progress model – it is more powerful than it may appear at this point.

For now, let’s explore how this continuum opens our eyes to a wider solution space.

seeing a wider solution space

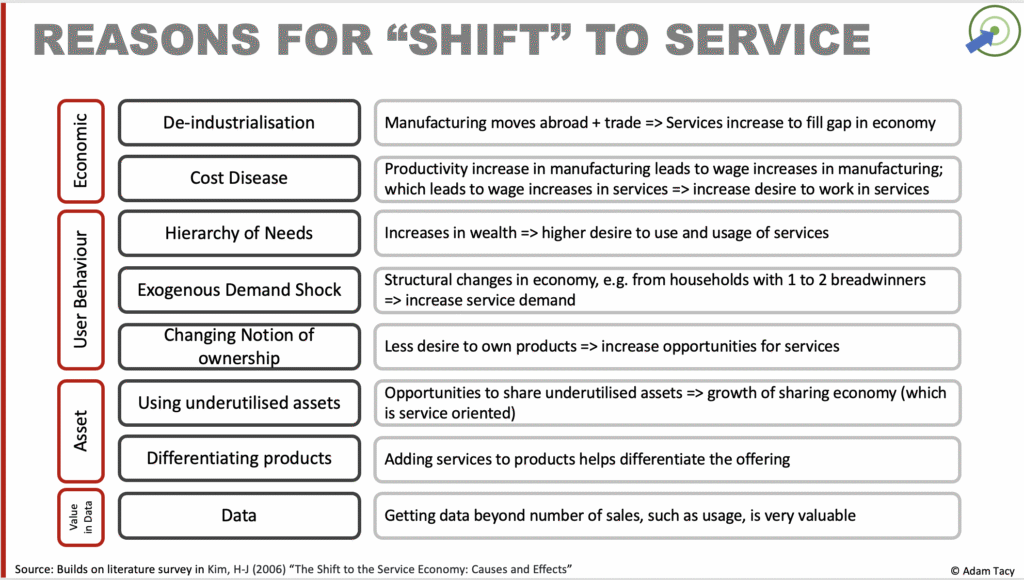

You may have heard of the “shift to service” or of servitisation. These terms arise from a goods-dominant perspective. In our service-forward world, these shifts are more accurately seen as a transition from enabling to relieving propositions, that is, from indirect to direct service.

This is not a significant change for us since we’re not engaged in the constraining debate comparing goods versus services. Instead, our logic implies we should naturally move our propositions toward the relieving end of the continuum to maximise value co-creation as discussed earlier.

Additionally, we should follow the beneficiary’s preferences. Several reasons contribute to their shifting preference toward relieving propositions. Some of these reasons, such as the “changing notion of ownership,” have already been discussed (see “Harnessing the Sharing Economy”).

Although, as we’ll see in value-through-progress, there are reasons a beneficiary may prefer moving towards enabling propositions.

It’s not just the solution space that feels larger, so is the business model space.

recognising a system of propositions

Increasing well-being often requires coordinating multiple propositions. This is the service system previously mentioned. The value-in-use model illuminates this, prompting questions about our scope as value proposers.

Can we expand our scope? What partners can we utilise? Should we offer choices in partners (eg for payment and delivery)? Or should we replace one member of the service system with another? Are there advances in well-being currently left for beneficiaries to coordinate?

finding a wider business model space

Similarly, since we’ve removed the exchange of embedded value for cash as a concept, we open ourselves to different business models – subscription, add subsidised etc.

To truly realise this benefit, we need a deeper discussion on service exchange and the role of price. That’s best taken when looking at value-through-progress where we discover price is really a signal of effort expected in return service exchange – which can be fulfilled through either direct exchange or indirect exchange through service credits.

So that’s quite some benefit the switch to value-in-use brings for us. However, there are still some constraints.

The model’s constraints

Value-in-use represents a significant evolution in our understanding of value. It effectively addresses many of the limitations associated with the value-in-exchange model. However, it also introduces certain constraints:

- defining value (well-being) remains challenging

- lacking clear mechanisms for value creation

- constraining definition of service

- only the beneficiary determines value

- lose actionable definition of price

- moving to direct service is all consuming

Here’s what I mean by those.

defining value (well-being) remains challenging

Replacing price with an increase in well-being as the measure of value is an improvement, yet defining well-being remains challenging.

An ideal definition would ensure consistency across different well-being dimensions and help us avoid neglecting significant aspects. For example, we’ve seen context is important, but the term “well-being” doesn’t immediately imply that importance. Similarly, non-functional elements of well-being may not be adequately considered. Say a beneficiary is looking to travel 100km, useful value propositions vary greatly depending on whether the individual has a driving license.

We could address part of this challenge by broadening the definition of “well-being” to encompass these elements. We’ll do just that in our next model – value-through-progress – although we will use the concept of “progress” instead of “well-being” as that also helps us with our next constraint.

lacking clear mechanisms for value creation

In the value-in-exchange model, the mechanism for value creation is straightforward: successive manufacturers in the supply chain embed increasing value into products. Whereas we talk of value co-creation through resource integrations In the value-in-use model.

Whilst the level of resource integration is fine for the marketing nature of where service-forward logics comes from, it falls short in providing the detailed levers needed to make innovation more systematic. We want to arrive at a better definition of innovation than improve resources and resource integration.

Why do beneficiaries engage with propositions? How do they decide between alternatives? What transpires during their engagement? What obstacles do they encounter? Answering these questions in a deeper way is key to enhancing our methods of value creation, innovation and growth.

constraining definition of service

Is the definition of service limiting? It’s defined, if you remember, in terms of competence, ie skills and knowledge.

service is the application of competence (skills and knowledge) for the benefit of another entity or the entity itself

Vargo & Lusch (2004), “Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing”, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 68, pp. 1-17

What about strength? A house moving service uses the strength of their employees (or their tools) to move heavy objects. Is strength a skill or knowledge? Perhaps we should talk of capabilities (and see resources as carriers of such capabilities).

only the beneficiary determines value

While the value-in-use model rightly emphasises the beneficiary as the primary determiner of value, it’s important to recognise that this model might overstate by claiming that beneficiaries are the only actors involved in this determination.

In certain scenarios, the actor proposing the value also determines value from their perspective.

For instance, if you wish to purchase a high-end sports car, the dealer will evaluate whether engaging with you will create sufficient value to justify their time. Similarly, during service provision, a provider might decide to withdraw resources if they perceive that value is not being adequately co-created.

Hence, it’s more precise to state that the beneficiary predominantly determines value, although the value proposition owner may also play a determining role in some cases.

lose definition of price

Back in the value-in-exchange model, price clearly indicated the value of a product, often set at the highest price a customer would pay.

However, the value-in-use model eliminates this direct link since there is no longer an exchange of embedded value. Nonetheless, price remains an obvious aspect of our daily life.

Ingenbleek asserts that price serves as a reward for service provision.

He sees pricing as an operant resource for firms, co-created with customers, through a process known as “value-informed pricing”. An approach that involves setting prices based on customers’ perception of value*.

Firms ”generate competitive advantage not only through value creation, but also through pricing”

price is the reward for the application of specialized knowledge and skills

Ingenbleek (2014) “The theoretical foundations of value-informed pricing in the service-dominant logic of marketing”, Management Decision 52(1)

Price becomes part of the value proposition

Kowalkowski (2010) “What does a service-dominant logic really mean for a manufacturing firms?”

Kowalkowski suggests that price is an integral part of the value proposition offered to the beneficiary.

This positions it as one of the inputs influencing beneficiaries’ decisions to engage with a proposition.

Vargo, Maglio & Akaka take a more meta view:

The process of co-creating value is driven by value-in-use, but mediated and monitored by value-in-exchange

Vargo, Maglio and Akaka (2008) “On value and value co-creation: A service systems

and service logic perspective”

They view value-in-use as the way to understand value co-creation and value-in-exchange as a means to measure relative value within surrounding service systems.

In the progress economy, we’ll propose that price indicates the effort expected, by a provider, in the service being exchanged for their service. This potentially is given in service credits. We’ll look at that in the value-through-progress model.

* Ingenbleek (2007) “Value-informed pricing in its organizational context: literature review, conceptual framework, and directions for future research”; Journal of Product & Brand Management 16(7): pp441-458.

move to direct service is all consuming

We’ve explored numerous reasons why beneficiaries are moving from indirect to direct service, a trend often described as the “shift to service economy” from a goods-dominant viewpoint. However, it’s constraining to believe the ultimate objective is to transition as fully as possible to direct service.

We need to be conscious that well-being may be enhanced for some beneficiaries by shifting from direct to indirect service or by preserving/improving existing indirect service.

There will always be a place for “craft” methods and for beneficiaries who relish the challenge of doing things on their own.

This consideration is perhaps not always apparent in general definitions and thinking of service-forward logics.

Relating to innovation

This is a significant topic that warrants its own dedicated discussion. For now, I’ll provide some key pointers.

The relational and open-ended time logic of value-in-use profoundly impacts innovation. It transforms innovation from a special event into a constant, every day, activity within the firm, with strong input from the beneficiary. Lusch and Nambisan identify the beneficiary as:

…having three broad roles:

Lusch and Nambisan (2015) ”Service Innovation: A Service-Dominant Logic Perspective”; MIS Quarterly 39(1): pp155-175

- ideator

- designer

- intermediary

Beneficiaries can articulate the increase in well-being they seek, their context, and how they use existing offerings to imagine new ones (ideator). As designers, they can help shape the development of offerings. Importantly, as intermediaries, they “carry” innovations from other markets and industries. Beneficiaries are exposed to service in multiple industries and markets. What they learn and expect in one area, they soon expect from you as well.

In fact, it is beneficiaries’ continuous efforts to enhance their well-being and exposure to offerings that drives their expectations for your offerings. Consequently, you must innovate to meet these evolving expectations or risk being left behind. This is the essence of Drucker’s “innovate or die”.

defining innovation

There are a couple of ways of interpreting the result of innovation in a value-in-use model. First we can take a service systems view, which tells that an innovation enhances the well-being, adaptability, and survivability of the service system compared to any existing offering. That is to say, for the service system:

This captures innovation improving the service system compared to an existing approach. The innovation may directly impact beneficiaries and/or value proposers (which in turn may indirectly benefit the beneficiary).

Alternatively we can take a more beneficiary perspective and simplify the above to the following:

where additionally the impact of innovation on the system’s well-being, adaptability and survivability is the same or enhanced compared to the existing offering.

The actual act of innovation is seen as creating new resource(s) from existing resources, ie:

rebundling of diverse resources that create novel resource that are beneficial (ie value experiencing) to some actor in a given context

Lusch and Nambisan (2015) ”Service Innovation: A Service-Dominant Logic Perspective”; MIS Quarterly 39(1): pp155-175

Beneficiaries can directly benefit from these new resources if offered as part of a new value proposition, such as new employee skills, goods, AI co-pilots, improved IT system interfaces etc. Or they may be resources internal to a value proposer – such as new processes, tooling, improved internal capabilities. Those internal improvements may indirectly benefit beneficiaries.

They could also involve new configurations of the service system, such as extending the service scope, swapping sub-service providers, or enabling real-time configuration by beneficiaries.

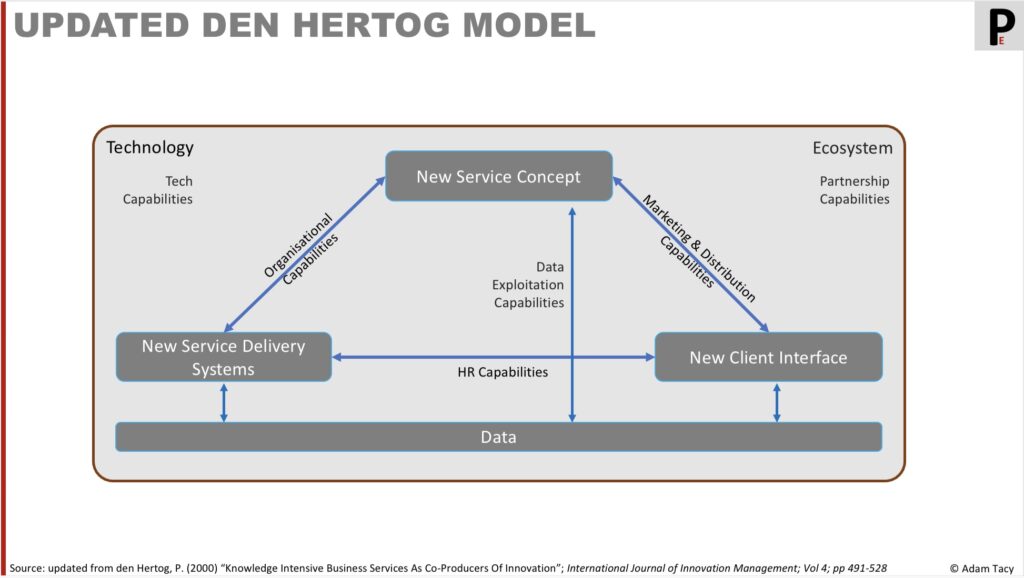

When we discuss innovation in detail we’ll leverage some updates to den Hertog’s model as a way of systematically hunting/explaining innovations in service provision.

However, this definition of innovation carries the challenge we lifted earlier with the definition of well-being (and adaptability and survivability) in that it does not include the necessary levers to make it more systematic. This in part is to do with the other constraint we raised about the mechanism of improving well-being is not sufficiently detailed.

Yet, our definition of innovation faces challenges, linked to two points we’ve already discussed:

- hard to define well-being (and adaptability and survivability)

- low details on the mechanisms relating to value co-creation

business model innovation

Separating value from price can obscure opportunities for business model innovation related to pricing.

For instance, the transition from a one-time payment to a subscription model isn’t immediately evident within the value-in-use framework. Of course we can torture the model to make it fit. One might argue that this shift enhances the system’s survivability by allowing beneficiaries to make smaller, recurring payments instead of a single large one. However, we must also consider its impact on other service system members, such as changes in cash flow.

We need a value model that uncovers new business models rather than struggle forcing existing ones to fit.

Value-in-use does open our eyes to opportunities like platform-as-a-service (PaaS) by addressing the desire to minimise inefficient resource usage. Eliminating the goods versus service debate also clarifies the concept of “servitization”.

To fully grasp alternative business models, such as subscriptions or advertising-supported frameworks, we must reintegrate price. We can achieve this by recognising value-in-exchange at a higher level, as suggested by Vargo, Maglio, and Akaka. Alternatively, as we will do in the progress economy, we can relate price to effort in service exchange (where business model innovation looks at how to minimise headline effort exchange).

editing from here

Organising the firm

Prahalad, C.K. & Ramaswamy, V. (2004). The future of competition: Co-creating value with customers. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Key take aways

The value-in-use model takes us a long way towards solving the constraints of the value-in-exchange model.

We’ve seen that with no point of exchange we free ourselves to understand what increase in wellbeing the beneficiary is trying to make. That encourages us to engage in dialogue. To customise our value propositions as we start to engage and as the act of service progresses.

By focussing on resources we’ve seen that we can remove the goods vs services debate of value-in-exchange. In fact we go a good way to fixing Levitt’s marketing myopia and opening up the solution space.

However we are still left with a final challenge – value (ie increasing system wellbeing) is complex to define and understand.

You’ll not be surprised that there is a further evolution to be done. One that nails down what value is in an actionable way and addresses price and value determination concerns. I call it value-through-progress.

Let’s progress together through discussion…