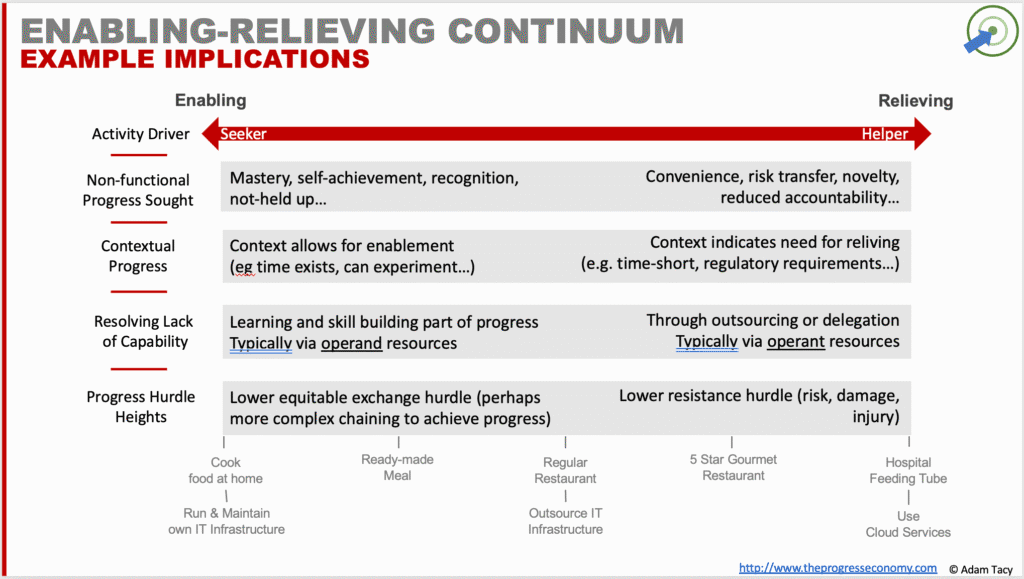

Seekers look to be enabled, relieved, somewhere in-between; propositions are enabling, relieving, somewhere in-between.

The positions tells us a lot about non-functional and contextual progress, progress hurdles and successful resource mixes. Understand the position of your Seeker and your proposition on the proposition continuum – innovate to close the gap, or, slide along the continuum to explore new proposals, new resource mixes, and new target Seekers.

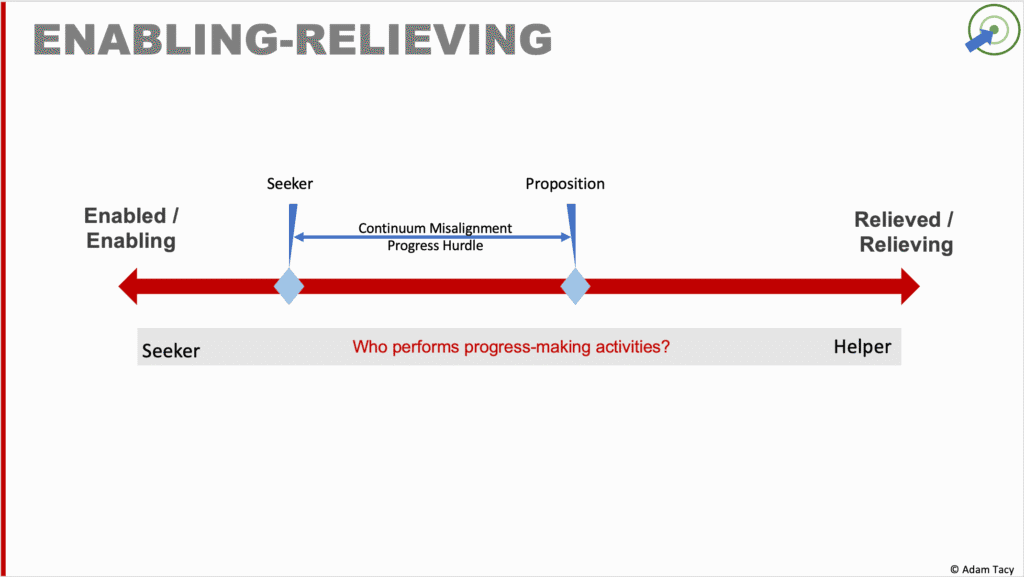

A mismatch reveals the continuum misalignment progress hurdle

What we’re thinking

Seekers often look for help to make progress, but not all Seekers want to be helped in the same way.

A growing number of Seekers are wanting to be relieved – to have someone perform the progress-making activities for them. Others want to be enabled – to carry out those activities themselves (for fun, achievement, cost concerns, or to not be held up). Most actually sit somewhere between these two points: there is a continuum.

Similarly, every progress proposition sits somewhere on this relieving-enabling continuum, its position signalling how many of the progress-making activities the Helper offers to perform.

The distance on the continuum between a Seeker and the proposition drives the Seeker’s perceived height of the continuum misalignment progress hurdle. Looking for a relieving proposition but there’s only a relieving one? Then the hurdle is high.

But for progress Helpers, this positioning offers more than just a descriptive view of who performs the progress-making activities. It becomes a:

- practical tool, useful for

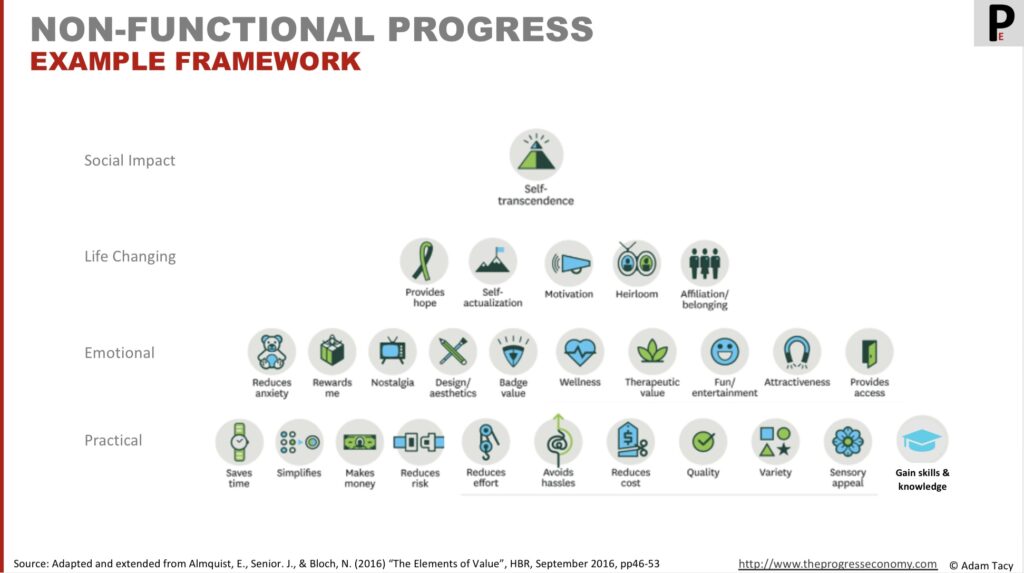

- understanding what a Seeker is looking for – enabling propositions, for example, support non-functional progress of mastery or sense of achievement and contextual progress of not being held-up; relieving propositions are for time-poor Seekers, or those that see a high resistance progress hurdle etc

- understanding the gap between an existing proposition (or market propositions) and target Seekers’ desires

- guiding which resource mix is most attractive to Seekers – enabling propositions are often goods-heavy, while relieving propositions are typically employee/system-heavy.

- framework for innovation – revealing opportunities to close misalignments, shift your proposition’s position, uncover underserved Seeker positions, and understand whether and why these present meaningful opportunities.

How do seekers want to be helped: relieved or enabled?

We take, as you know, a very progress-first first view of the world:

- Seekers actively try to make progress through a series of progress-making activities – essentially, integrations of resources that carry capabilities

- Seekers often lack the necessary capabilities – skills, knowledge, tools, physical attributes, time, etc – needed to succeed

- Helpers step up by offering propositions: supplementary capabilities carried by a proposition specific resource mix – designed to close these capability gap and accelerate the Seeker’s progress

When Seekers lack the necessary capabilities to progress, they typically face two choices. They can generate themselves (or find them in resources in the environment), or more typically they engage a progress proposition.

But not all Seekers want help from a proposition in the same way. Some want to achieve a sense of accomplishment, or to not be held-up, or…these Seekers want to perform the majority, or all, the progress-making activities themselves. Others want someone else to perform the majority, or all, the activities as they lack time, or fear injury/damage, etc. Many Seekers position themselves somewhere in between.

Thus we uncover the relieving-enabling continuum. This builds on Vargo and Lusch view of enabling and relieving service provision in Why service? (see lower for the discussion of how the relieving-enabling continuum aligns to existing thinking)

Often we talk of this continuum in relation to propositions, but in true progress economy thinking, it starts with the Seeker.

Who performs the progress-making activities?

As we just mentioned, some Seekers want to be relieved from performing any of the progress-making activities. This preference is part of a growing trend commonly called “the ongoing shift to the service economy“. There are many reasons for this shift – economic drivers, changes in user behaviour, asset utilisation opportunities, strategic value of data – but there are also many reasons why a Seeker might want to be relieved in the base case – lack of time, concerns over making errors etc.

These Seekers pursue relieving propositions which are typically fronted by employees, AI, or operant systems in a Helper’s proposition’s resource mix.

Seekers integrate with these, typically, operant resources – resources that act on other resources to create progress – and those operant resources perform the progress-making activities (sometimes making use of resources/capabilities not visible to the Seeker).

Other Seekers want to be enabled. They prefer to make progress themselves. Sometimes, this might be as simple as using resources they find in their environment. For example, using a fallen tree branch as a lever. More commonly, in our complex world, these Seekers are drawn to enabling propositions, which are offerings that provide goods, tools, locations, or operand systems (distinct from operant systems we previously mentioned).

When Seekers integrate with these, typically, operand resources – resources that must be acted upon to create progress – they drive the progress-making activities themselves. Sometimes ownership of these resources moves from Helper to Seeker, sometimes not. Seekers may reuse resources they have acquired when making a new progress attempt (and may even use resources acquired in one progress attempt in a different progress attempt).

And of course, the decision to seek relieving or enabling is phenomenological and can alter between attempts – I might have a car (enabling) but still take a train (relieving) for some journeys. Even sometimes for the same physical journey but where non-functional/contextual progress differs on a particular attempt.

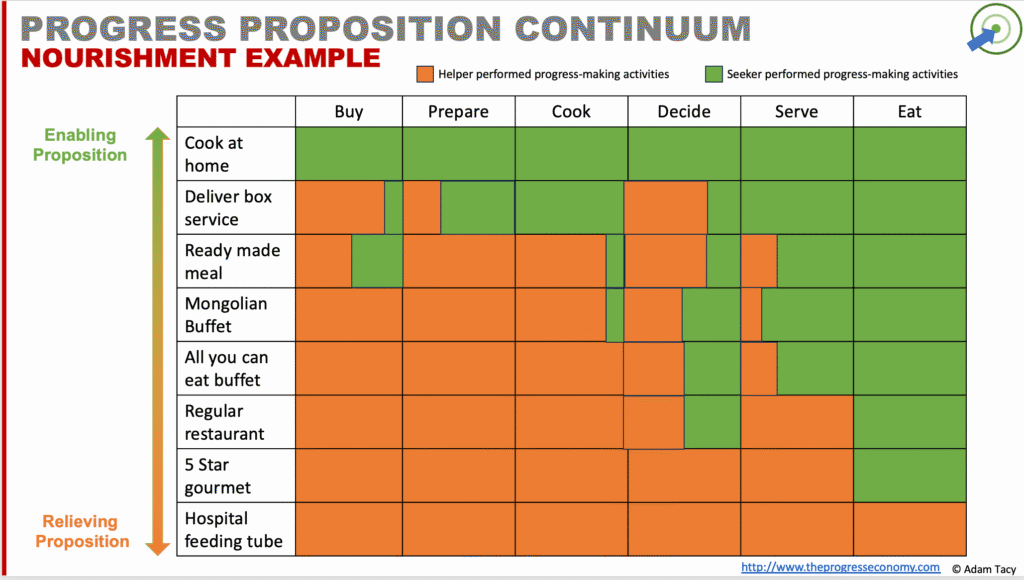

Let’s look at this through a practical example – getting nourished.

An example: Getting nourished

Consider the seemingly simple functional progress of getting nourished. We can break this down into the following distinct progress-making activities:

- obtaining the ingredients (buy)

- preparing the ingredients (prepare)

- cooking the meal (cook)

- deciding what to eat (decide)

- serving the food (serve)

- eating the food (eat)

Different propositions align to these activities in different ways, with Seekers either enabled to perform the activities themselve, relieved of the effort, or often somewhere in between.

At the highly enabled end of the continuum sits home cooking. The Seeker performs every activity – deciding on a recipe, buying ingredients, preparing, cooking, serving, and finally eating. Along the way, they draw on a chain of enabling propositions: a supermarket for ingredients, utensils and cookware, an oven, serving dishes, cutlery, and more. Success depends not only on the availability of these propositions but also on the Seeker’s ability to co.ordinate them effectively.

Moving along the continuum, Seekers can choose to be progressively relieved of effort. A ready-made meal still requires buying from a supermarket and perhaps some simple preparation/warmig – microwaving or baking – but much of the decision-making, preparation, and cooking is already done. A restaurant takes this further: the Seeker need only decide what to order and eat, while all other activities are handled by the Helper.

At the fully relieved extreme, nourishment comes via a hospital feeding tube. Here, every progress-making activity is performed by others, with the Seeker contributing little or nothing. This, of course, is typically a scenario driven by necessity rather than choice.

Enablement vs. relief is not just a design choice – it’s a growth lever. Companies that continually rebalance this mix, in line with evolving Seeker expectations, are the ones that expand markets, avoid disruption, and shape the competitive landscape.

The ideal proposition has a position that identically matches the Seeker’s position. Where there is a misalignment, we find the continuum misalignment progress hurdle – which is highest if a Seeker looks for relief and only finds enabling (or vice versa). A Seeker needs to judge if the height of that hurdle is acceptable to them to attempt progress.

Whilst who performs the majority of the progress-making activities positions the Seeker and propositions on this continuum, there are a variety of reasons behind where a Seeker positions themselves for any particular progress attempt.

Looking to be relieved or enabled

Being relieved means asking someone else to perform most, if not all, of the progress-making activities on your behalf.

Seekers often pursue relief for convenience or to save time. But the drivers usually run deeper. Relief allows them, for example, to offload complexity, reduce risk, escape accountability, or free them for other tasks/progress attempts. A Seeker may choose a restaurant not because they lack the skill to cook, but because they want to dedicate their cognitive and emotional bandwidth elsewhere.

The same holds in B2B. A company may outsource IT not just to reduce internal management effort, but to transfer operational risk and ensure greater reliability through a trusted expert. They often also wish to have access to the latest technology without capital investment and reduced equitable exchange through being part of a larger body.

While we observe a clear, ongoing shift towards Seekers preferring relieving propositions (see later), there remains a significant cohort who want to be enabled – that is, they want to perform the progress-making activities themselves.

For some, this is about maintaining control. But other Seekers look to be enabled because they are pursuing learning, mastery, or the intrinsic satisfaction of making progress through their own efforts.

There are four main factors that underpin a Seekers position on the enabling-relieving continuum:

- non-functional progress

- contextual progress

- lack of capability

- progress horde height

Each gives deep insight into what a Seeker is looking for (and what your proposition should address).

Let’s dig into these, beginning with non-functional progress.

Role of non-functional progress

Non-functional progress is one of the strongest forces shaping where a Seeker positions themselves on the enabling–relieving continuum.

At times, the choice is straightforward: a Seeker simply wants to be enabled or relieved. More often, deeper motivations surface. A desire for relief may reflect the pursuit of convenience, exploration (such as trying new cuisines), or unique experiences (like a Michelin-starred meal). Relief can also be about risk transfer, shifting responsibility for outcomes to someone else. A company, for example, may engage a cybersecurity partner not only to fill technical gaps but to transfer reputational risk and provide reassurance to its board and regulators.

Enablement, by contrast, aligns with self-achievement, admiration, or the intrinsic satisfaction of doing something personally. People grow their own food, brew their own beer, or cook elaborate meals not just for the result but for mastery, recognition, or fulfilment.

The same dynamics play out in business. Many organisations prefer enablement to avoid friction, bottlenecks, or third-party dependencies. This sits at the heart of transaction cost economics and the theory of the firm: the classic “make vs. buy vs. ally” decision reflects a judgment about where to internalise progress-making activities and where to externalise them.

We can look to Almqvist’s hierarchy to map common non-functional progress elements.

driven by context

Context often determines when and why relief becomes attractive.

At the office, cooking a meal from scratch is often impractical; after a long day, fatigue can make a home-delivered pizza irresistible; or on a business trip, eating out may be the only feasible choice.

The same principle applies in B2B. A manufacturer may outsource last-mile logistics during peak season. It can handle distribution most of the year, but during demand spikes, facilities and fleet become constrained. Relief allows the company to maintain service levels without overinvesting in permanent infrastructure.

Some contextual progress is injected by regulators, and this can push a Seeker towards relieving propositions. For example, performing work on gas appliances often requires the performer to be certified. Or new legislation might mean a Seeker turns to specific experts in the short term to ensure compliance.

But this also works in reverse. A Seeker might want to be enabled due to the context rather than relieved. The current growth in use of Gen AI Large Language Models leaves Seekers at the mercy of the limited number of providers, and with security risks of their data. To minimise, Seeker’s may decide to use enterprise versions of the LLMs, or even start running them in-house.

Context is always tied to the specific progress attempt. Even for the same Seeker, preferences can shift dramatically between attempts. A knowledge worker may prefer to be enabled by preparing their own lunch one day but be relieved by catering the next, depending on meetings, time, and setting.

Relief driven by lack of capability

Capability gaps are another driver of positioning.

Take a lack of time. This can often be viewed as tipping a Seeker toward relieving propositions. Though we always need to be careful in our thinking, it can push towards enabling – preparing a quick sandwich at home can often be faster than going to a restaurant for lunch (but both might be slower than getting food delivered).

Beyond time, shortages of tools, skills, or knowledge can force a positioning towards relief. Some cuisines, like Fugu (pufferfish), require expert preparation because of safety risks. Similarly, a mid-sized enterprise may adopt a cloud-based HR platform not just for convenience but because it lacks the expertise and infrastructure to build and maintain its own system.

There’s also an important nuance: a lack of skills often pushes toward relief, but sometimes gaining those skills is the progress. A Seeker may deliberately take on the slower, harder enabling path because growth, mastery, and learning are themselves valued outcomes.

Relief driven by progress hurdles

Progress hurdles also shape the choice between enablement and relief.

Resistance, adoptability, confidence (in proposition and Helper), and equitable exchange all matter. It may not be socially acceptable to cook lunch at the office (part of resistance hurdle)), making relief more practical. A business might avoid building its own data centre because the required capital, risk exposure, or equitable exchange feels prohibitive.

Yet hurdles can also push toward enablement. If the perceived price of a relieving option feels too high, or if confidence in the Helper’s ability is low, the Seeker may prefer to enable themselves. For example, if you already own a car, using it is less effort than booking a ride-share. Similarly, a business might prefer in-house development when it doubts a vendor’s responsiveness or fears lock-in.

Editing below here

Understanding Seeker’s positioning leads us to positioning progress propositions.

The Progress Proposition Continuum

Let’s turn this thinking into a tool and framework that you, as a Helper, can use for improving innovation, sales, and growth: the progress proposition continuum.

Progress proposition continuum: a continuum between enabling and relieving propositions that reflects how many of the progress-making activities the seeker performs

It hopefully makes sense that a proposition also has a position on the continuum. Some propositions will be more relieving, others more enabling. Proposition positioning is typically shaped by the dual of the Seeker’s concerns, ie:

- non-functional progress offered

- context of the progress offered

- offered resource types

- the height of progress hurdles

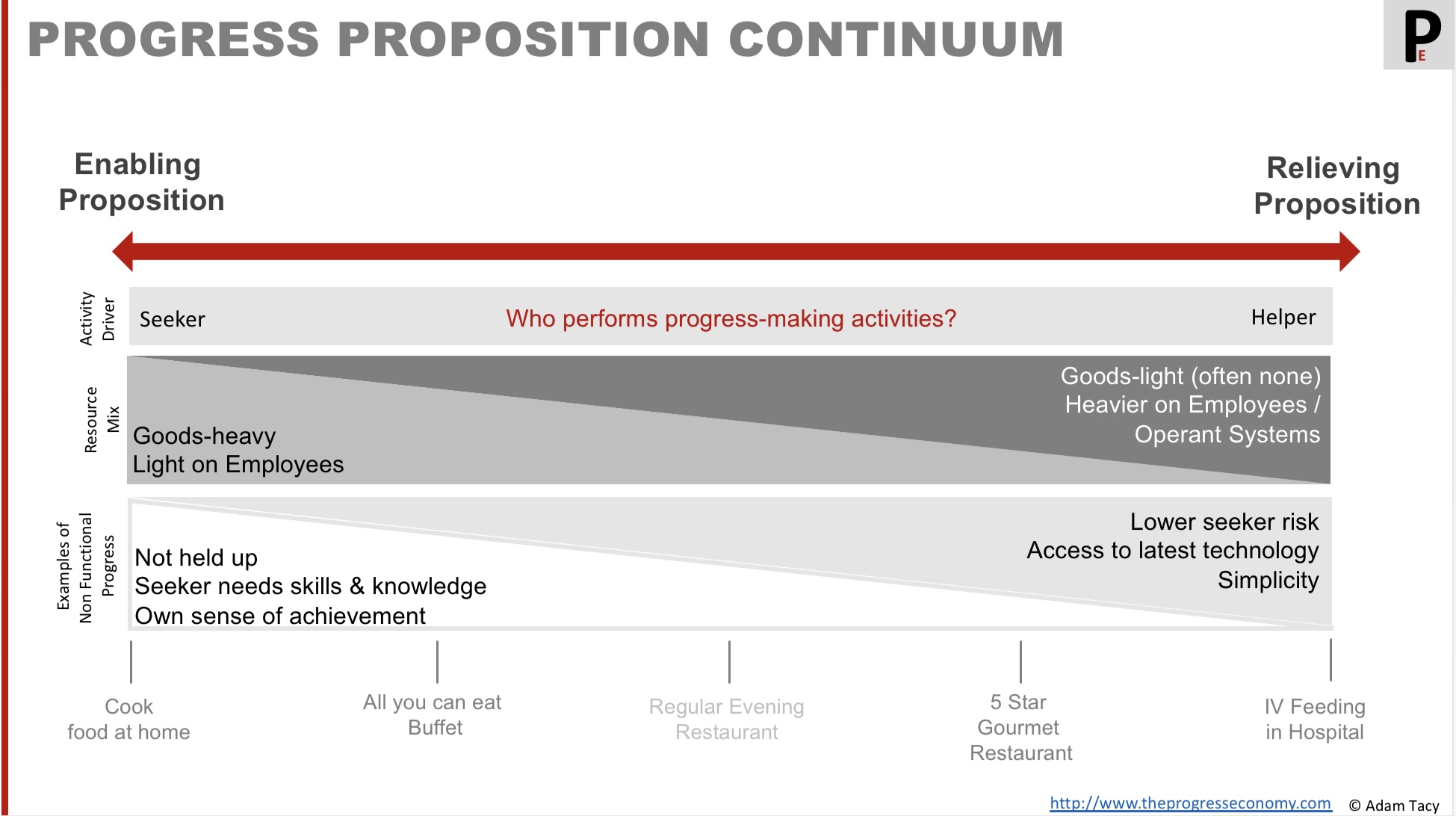

Visually we can see this continuum as following:

At the top we find our two extremes of propositions; enabling and relieving. Just below that is the indication of who performs the progress-making activities. Then there is an indication of a typical resource mix, the non-functional progress supported and how our getting nourishment example fits.

Enabling propositions

Helpers design enabling propositions to empower a Seeker, allowing them to undertake progress-making activities themselves.

enabling propositions: propositions that enable the progress seeker to perform the majority of the progress making activities

A Helper freezes their skills and knowledge of helping to make progress into an object (physical or digital). This object becomes the proposition. The Seeker then unfreezes those skills and knowledge through acts of resource integration at the time and place they attempt to progress.

Imagine a Seeker looking to entertain themselves by listening to music. A Helper will capture a band’s performance (skills & knowledge of playing) as a digital file and make it available on a streaming site. A Seeker will stream that performance in their favourite mobile app, at which point the bands performance is unfrozen.

This is the definition of goods in the Progress Economy. It extends beyond traditional physical goods to include physical resources which are goods where ownership is not transferred, as well as data and locations.

Key characteristics of enabling propositions:

- The Seeker drives the activity – the customer is actively involved in achieving their progress; they are not outsourcing the effort

- Appeals to Seekers who want control, self-actualisation, or enjoyment in the process

- Relies heavily on goods (operand resources) – typically goods-heavy, employee-light

- Higher Seeker involvement and risk – progress depends on the Seeker’s skills, time, and knowledge

- Need for greater co-ordination – often requires Seekers to co-ordinate several propositions themselves to achieve their progress sought

- Examples:

- Cooking a meal at home using home grown ingredients (vs. dining out)

- Home improvement DIY kits

- Self-serve technology platforms

- Gym memberships (vs. personal training services)

Relieving propositions

Helpers design relieving propositions to relieve a Seeker from performing progress-making activities.

relieving propositions: propositions where the progress helper performs the majority of the progress making activities

A Seeker generally integrates with an agent of the Helper and that agent performs the progress-making activities. Those agents are employees/AI and operant systems.

Key characteristics of relieving propositions:

- Minimises effort for the Seeker – the customer’s involvement is low; they are “relieved” of doing the work themselves

- Reduces Seeker risk – the Helper typically provides the expertise, systems, and resources needed to ensure reliable outcomes

- Relies heavily on employees, AI or systems (operant resources) – these propositions are often goods-free, leaning heavily on employees, processes, and technology to deliver outcomes

- Prioritises convenience, simplicity, and speed – Seekers choose relieving propositions when they want frictionless, low-effort progress

- One stop shops – a relieving proposition often covers a wider scope of progress-making activities of a progress journey (eg amazon covers sourcing, buying and shipping)

- Examples:

- tube-feeding in a hospital (the ultimate relieving proposition)

- Concierge services

- Managed IT services

- Full-service home cleaning

Relating to The classic goods-service continuum

The idea of a continuum of help is not new. Traditional business thinking has been shaped by goods-dominant logic, which draws a sharp distinction between goods and services.

This perspective gave rise to the classic goods-service continuum, popularised by Palmer and Cole in Services Marketing: Principles and practice. They recognised that many offerings sit between these two extremes, noting that tangible goods often come with supporting services, while major services frequently rely on supporting products.

However, this continuum has limited relevance in the Progress Economy.

In the Progress Economy, the debate between goods and services (plural) is removed. Goods are viewed as distribution mechanisms for service. If we attempted to reframe the goods-service continuum as a service-service continuum whilst maintaining the tangible-to-intangible range, it would add little strategic insight. It would simply reposition the old logic without truly advancing our understanding.

A more useful lens is provided by Vargo and Lusch in Why service?. They introduce the distinction between direct and indirect service provision. Services can be delivered directly (for example, by people, AI, or systems) or indirectly (where service is “frozen” within goods). This reframes the conversation away from the goods-service divide and towards a direct-indirect continuum of service provision.

Better still, Vargo and Lusch go further, referencing Normann’s influential work Reframing business: when the map changes the landscape. Norman introduces the critical distinction between enabling and relieving service. To quote Vargo and Lusch:

Norman’s distinction is essentially based on which party’s operant resources are most central to value creation. In relieving processes, the firm is using its operant resources to provide relatively direct service for the consumer and in enabling processes, the customer is primarily using relatively more of his or her operant resources to act upon resources provided by the firm

Vargo & Lush (2008) “Why service?”

Rather than framing propositions along a goods-service or direct-indirect continuum, the Progress Economy evolves this thinking to an enabling-relieving continuum. The critical question becomes: Whose operant resources are primarily used? In other words, who performs the majority of the progress-making activities: the Seeker or the Helper?

This shift in perspective is far more actionable for leaders. It directs attention to how propositions are constructed, how value is co-created (ie how progress is made), and ultimately, how businesses can best align their offerings with the real progress their Seekers want to make.

Implications of the continuum for progress propositions

When looking at enabling and relieving propositions we pulled out some implications of each. Let’s look a bit deeper.

Expectations on seeker

Expectations on seekers vary based on whether the proposition is relieving or enabling. Relieving propositions have lower expectations on seeker knowledge and skills, while enabling propositions demand a higher level of proficiency.

Even the least demanding proposition of either type requires the seeker to define their progress sought. It may seek regular feedback on progress reached during the attempt, with more engaged propositions possibly seeking feedback after completion.

Equitable exchange

Relieving propositions are well-suited for seekers not inclined, or able, to acquire the resources they lack. These seekers may feel they lack the time, skills, or knowledge to progress, and the helper relieves them of this resource deficiency. However, relieving propositions often come with a higher equitable exchange hurdle, reflecting the increased effort required by the helper. Additionally, they only temporarily alleviate the seeker’s lack of resources.

Requirements on knowledge and skills

Contrastingly, enabling propositions expect more from seekers in terms of skills and knowledge. Seekers engaging with enabling propositions need to understand how to use the propositions. They may additionally need to discern the order in which to apply them.

Take a simple example of hanging up a picture. A handyman relieves you the effort here. But doing it yourself requires knowledge of various tools needed especially how to hang items of particular weights on different types of walls.

While enabling propositions often outline detailed progress-making activities, it’s ultimately up to the seeker to follow through. Deviations from the proposed activities – instructions, recipes, manuals etc – likely lead to value co-destruction. Although occasionally this may result in innovative uses.

Composing Resource mixes

A relieving proposition, by definition, relies more heavily on the helper’s operant resources to execute progress-making activities. Consequently, their progress resource mixes is anticipated to be skewed towards operant resources, with employees and certain systems (such as Artificial Intelligence, web browsers, etc.) playing a central role. Though it may certainly include some operand resources.

Whereas the resource mix of an enabling proposition reflects that the seeker’s operant resources are driving the progress-making activities. Therefore it is likely to be heavier on operand types of resources – those that need acting upon for progress to be made. Here we’re thinking goods, locations, and some types of systems (typewriters, dumb call centre routers, etc).

Whereas an enabling proposition indicates the seeker’s operant resources drive the progress-making activities. This suggests the progress resource mix will emphasise operand resources – those that need to be acted upon for progress to occur. These include goods, locations, and certain systems (like typewriters, basic call center routers, etc.).

Offering physical resources – goods where access is only temporary – moves us slightly along the continuum, but can still be thought of as enabling so long the seeker drives the activities. Hiring a tool you use is enabling; using a train is generally not (unless for some reason you become the driver).

Ownership of resources

Often the seeker acquires ownership of the operant resources offered by the helper with the first engagement. Subsequently they can use any non-consumed resource again whenever and wherever they want. Once you have a hammer you can hammer whenever and whatever you want. Unfortunately, if its a consumable, say ingredients in our running example, then once used they are gone.

However, it’s worth noting that when a resource is not in use, it is not helping anyone progress (co-create value). So enabling propositions are often inefficient in resource usage. Leading to the innovation opportunity of how can they be made more efficient?

transfering risk

Relieving propositions support reaching a different range of non-functional progress. A key one is reducing risk. Since the helper drives the progress-making activities the risk of failing the attempt is on them (or so the seeker is likely to believe). They also support saving time, simplifying, reducing effort, often increasing quality and so on. But doesn’t reduce cost (equitable exchange) or help gain skills and knowledge.

Access to latest technology

Moreover, by using relieving propositions, seekers can gain access to the latest approaches and technologies. In a subscription service for tools, a seeker should expect technology refreshes in the offering.

Revealing a progress hurdle: continuum misalignment

The enabling-relieving continuum does more than describe how propositions are positioned. It also reveals one of 6 critical progress hurdles.

As Bettencourt, Vargo, and Lusch note in A Service Lens on Value Creation (2014):

…a company must decide where on a continuum of “enabling” to “relieving” service it will be because this impacts the service role of the customer.”

Bettencourt, Lusch, and Vargo. (2014) “A Service Lens on Value Creation”

The key insight in the Progress Economy is this: it’s not just propositions that sit on this continuum, Seekers do too. And importantly, a Seeker’s position isn’t fixed. It can shift from one progress attempt to another.

This dynamic introduces the concept of continuum misalignment Simply put, the distance between where a Seeker positions themselves on the continuum and where a proposition sits indicates the size of this hurdle.

The larger this distance, the greater the hurdle. For example, if a Seeker wants to be fully relieved of effort, but a proposition is fully enabling (requiring them to take on all the progress-making activities themselves), the hurdle is at its highest.

Of course, a hurdle is not a barrier. Seekers may still choose to engage if their phenomenological judgement of value (progress) outweighs their judgement of overcoming the hurdle. However, Helpers should actively seek to minimise this misalignment for their target Seekers, either by repositioning their propositions along the continuum or by more precisely targeting Seekers whose position naturally aligns with the proposition’s design.

This is where competitive advantage can emerge: by reducing progress hurdles through better alignment, organisations can remove friction, accelerate adoption, and increase the likelihood of sustained engagement.

Relating to innovation and sales

The great thing about the continuum is it provides an excellent framework for innovation, allowing progress helpers to explore new positions, adapt their service mix, understand shifting seeker positions, and identify supplementary propositions. This dynamic approach enables progress helpers to continually refine and enhance their offerings to better meet the evolving needs of progress seekers.

Closing misalignments

Exploring New Positions

By navigating along the continuum, progress helpers can explore new positions that cater to the evolving needs and preferences of progress seekers.

Why not explore the impacts of moving towards a relieving service – applying AI or servitisation/platform asa service? Or moving the other way to attract seekers looking to learn new skills.

These fresh positions often lead to innovative propositions that better align with the changing landscape of progress.

Adapting the resource Mix

The ability to update the resource mix is a key feature of the continuum. Progress helpers can assess and modify the mix of resources and activities offered to align more closely with the specific requirements of progress seekers.

This adaptability ensures that propositions remain relevant and effective in achieving progress.

Hunting unserved Seekers

Identifying Supplementary Propositions

Helpers can introduce supplementary propositions that help narrow the misalignment hurdle. Whether acting as the incumbent helper or a challenger/complementer, they can refine their offerings to reduce the gap between their propositions and progress seekers’ needs.

As an illustrative example of the last point, consider the “cooking yourself” proposition. If a seeker lacks cooking skills and knowledge, the progress helper can enhance the service mix by including resources such as cookbooks, online instructional videos, physical or online cook-along sessions, and on-demand assistance. This comprehensive approach not only addresses the seeker’s skill gap but also offers a more holistic solution for achieving progress.

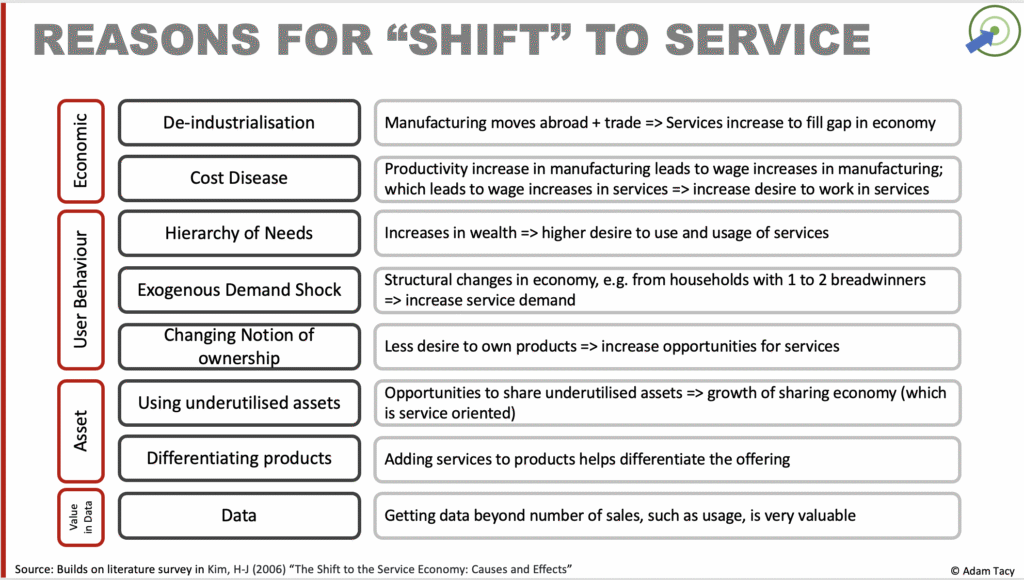

There’s a growing preference to being relieved

Seekers are increasingly prefering relieving propositions. This has been called the shift to the service economy. The main reasons for this can be summarised as follows:

Within these reasons we can distill the four points above: non-functional, context, lack of resource and progress hurdles.

Why this matters

Understanding whether a Seeker wants to be relieved or enabled—and why—isn’t just a design question. It’s a strategic imperative:

- It affects product-market fit.

- It influences resource allocation.

- It shapes operating models and revenue streams.

- It drives how you differentiate in increasingly crowded markets.

It’s a lever: https://theprogresseconomy.com/sliding-along-the-progress-continuum/

In the Progress Economy, winning propositions are not just those that offer the right solution—but those that align with the Seeker’s preferred mode of making progress at that moment.