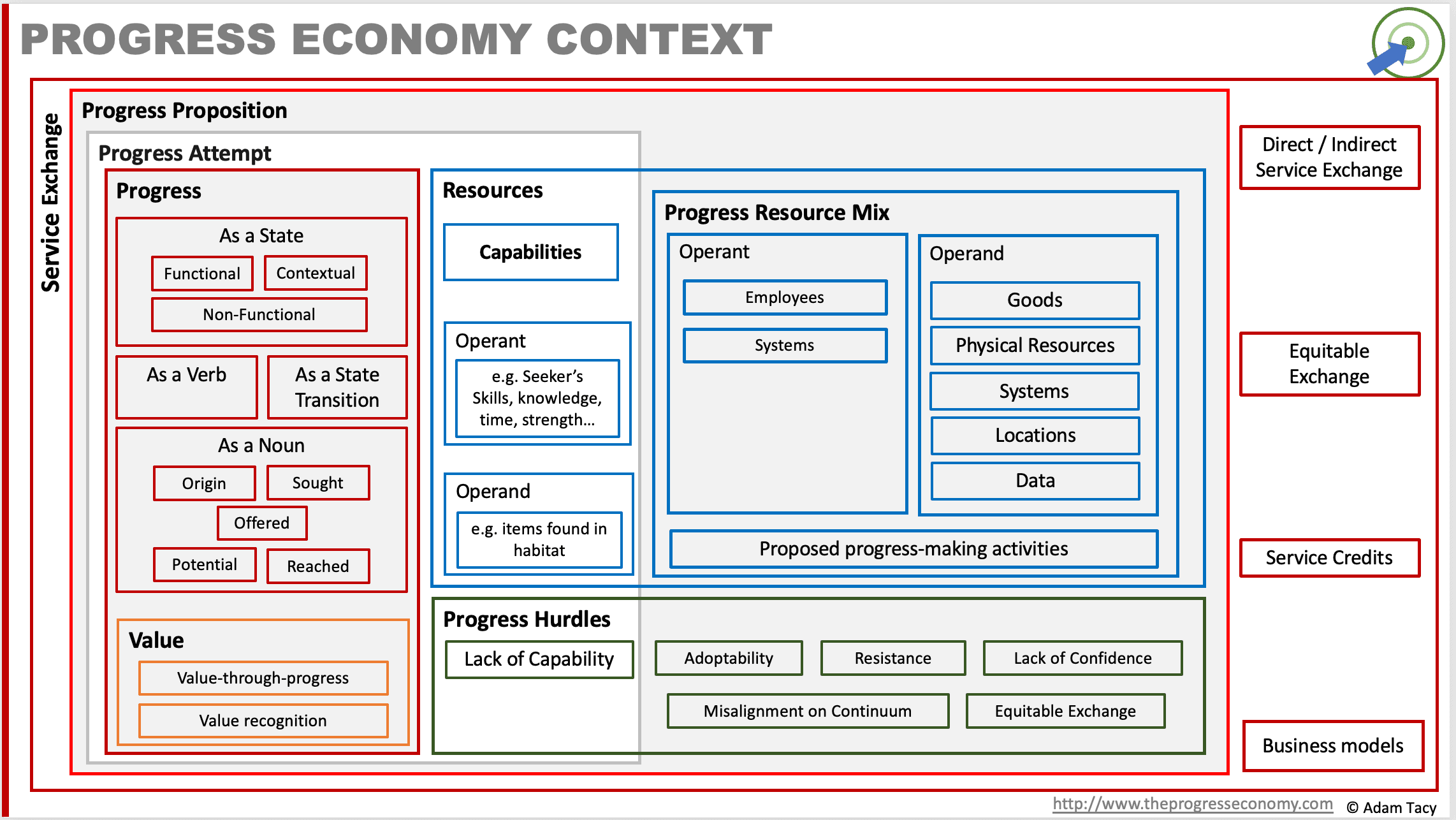

Four nested layers of context build into the progress economy – it’s a gateway into understanding how to fix your innovation, sales, and growth problems.

What we’re thinking

The Progress Economy is a framework for a progress-first world. One that an offers to fix your innovation, sales and growth problems. A way to explore the framework is through four nested contexts. Each one building on the previous – deepening our understanding and revealing the levers to drive innovation, sales, and growth.

Here’s the four contexts:

- progress – what does it mean to make progress? And how does value emerge from it?

- progress attempts – How do Seekers pursue progress? What is the foundation progress hurdle – the lack of capability?

- progress propositions – how do Helpers offer to help that progress journey, who does the work, who has the capabilities? What are the additional five progress hurdles a proposition brings?

- progress economy – how does it all connect into a functioning system of service exchange, and why?

Together, these layers offer a full-stack view – from individual motivations to system-level dynamics. The et of levers they expose offer a more systematic, and broader, approach to sales and innovation, driving growth.

This forms one of two architectural views of the Progress Economy, the other being the functional operating model.

Let’s get contextual

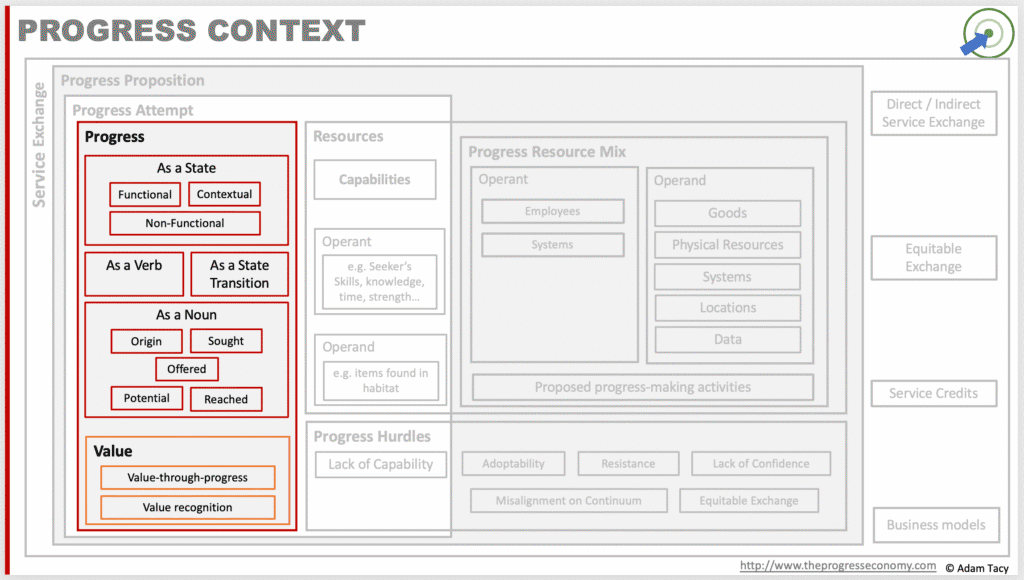

Progress is a framework. We see this through looking at progress economy as a hierarchy of contexts, each building upon the previous.

There are four contexts we recognise:

- Progress

- Attempts

- Propositions

- Service exchange

These contexts expose the key concepts of the Progress Economy and structure that links them into a cohesive framework. In doing so, they reveal actionable levers to drive innovation, boost sales, and accelerate growth.

Let’s take a closer look at each as we build up the foundation of the Progress Economy.

Progress context: the fundamentals

Progress is the beating heart of the progress economy.

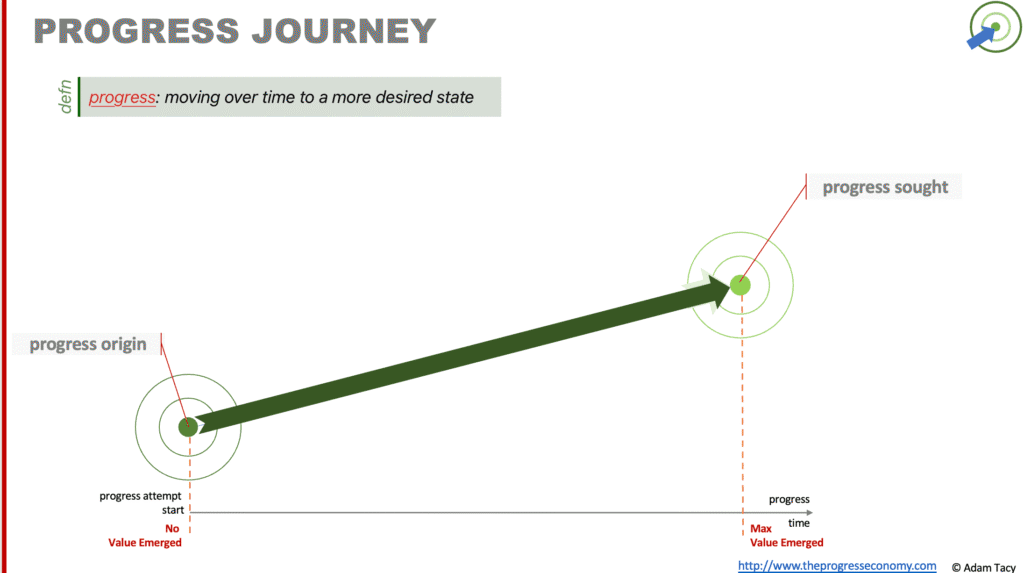

progress: a move, over time, to a more desired state

Value, in all of its forms, is a specific set of progress comparisons. In the progress economy we focus on enabling better progress; value follows.

It is in the progress context that we find the fundamentals of the progress economy: progress and how value emerges as comparisons of progress.

Making Progress

Perhaps not surprisingly, we find the concept of progress within this context. It is viewed 5 complimentary ways, as a:

- verb – the act of moving, over time, to a more desired state

- state – made up of functional, non-functional and contextual elements

- measure – judging amounts of progress made/possible

- noun – naming the useful progress states on the progress journey

- state transition – another useful way of observing progress similar to being a verb

Each works together to give a rich description of what is progress and how it is achieved. Supporting this narrative is exploring several named progress states:

- progress sought – the Seeker’s more desired state

- progress origin (seeker) – the Seeker’s current state

- progress origin (proposition) – the start state of a proposition

- progress offered – the state a proposition offers to help reach

and several phenomenological judgements:

- progress reached – a judgement of how much progress has been made by a point in time

- progress expected – a judgement of how much progressed should have been made by a point in time

- progress potential – a judgement of how much progress can be made from a point in time

From these we can now describe the Seeker’s progress journey. And indeed, we introduce a progress diagram to visualise this.

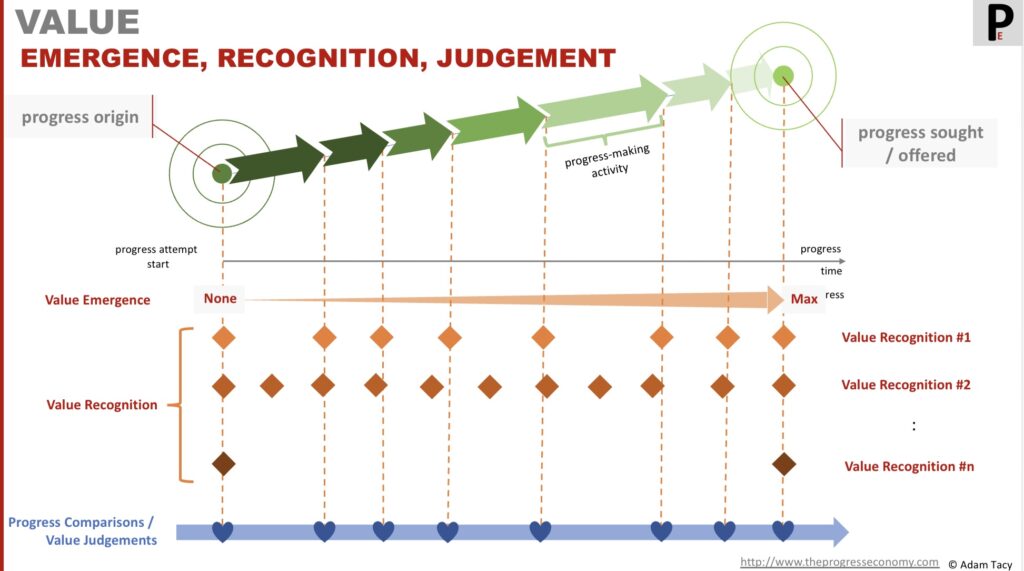

Value: emerging from progress

This context also lays the ground work for showing how value, in the Progress Economy, emerges through progress – from comparisons of progress. Notably:

- potential value – how much progress could be made compared to what I am seeking

- emerged value – how much progress has been made compared to my expectations

- recognised value – how much of that emerged value is meaningful to a specific seeker on that specific attempt

Predominantely it is the Seeker than makes these comparisons, before, after and continuously during a progress attempt. However, in some propositions, a Helper additionally makes comparisons, chosing to withdraw their offered resources if they feel progress is, or will not be, sufficient.

We also find the concept of value recognition – the process of a Seeker turning emerged value Into something meaningful to them.

Imagine your progress is simply moving 100km. It’s easy to see that the full value emerges only when you reach the destination, and no value has emerged before you begin. But is the value that emerges as you progress meaningful to you? It depends. If you make 80km and can continue the journey tomorrow, yes. If you have to be at 100km today and only make 80, then that 80 is pretty useless. It’s as meaningful as 50km, or 5, or 0.

The next context looks at how progress is made.

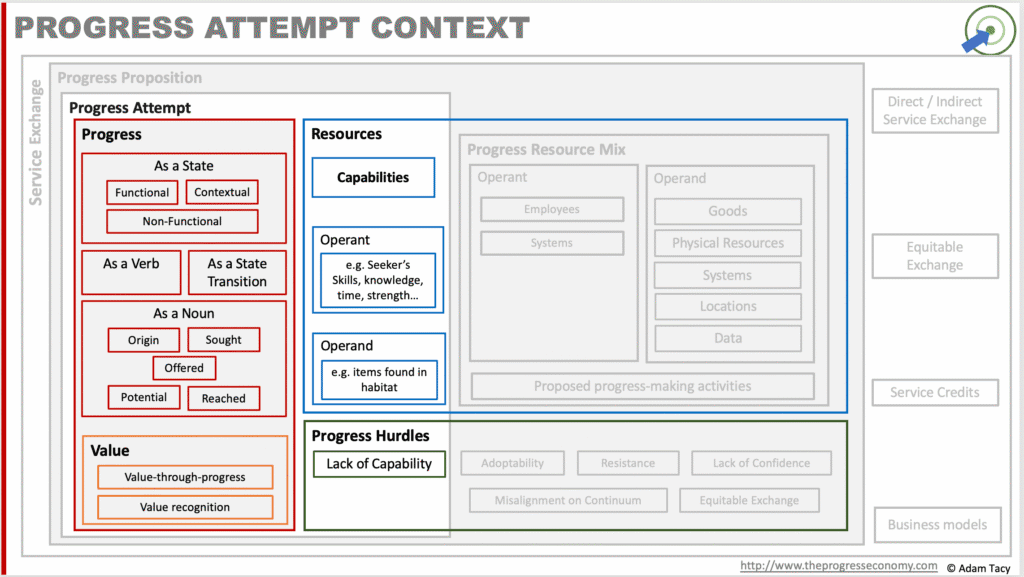

Progress attempt context: the mechanics

Now we have established progress as the movement from one state to another, more desired one, the natural next question is: how does that movement happen? The answer lies in the progress attempt. This is a structured effort by a Progress Seeker to move from their progress origin toward their progress sought.

Every attempt consists of progress-making activities. These are discrete actions that apply available capabilities to overcome specific obstacles. And those capabilities are carried by resources already available to the Seeker, or that can be readily found in their environment.

Critically, one type of resource must act upon another for this to occur. We refer to:those resources as operant; other resources, that need to be acted upon for progress to be made, are known as operand resources.

Operant Resource

acts on other resources resulting in progress being made

Operand Resource

need to be acted upon for progress to be made

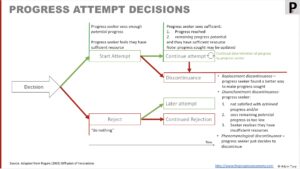

Seekers that do not have the necessary capabilities to make progress face the foundational progress hurdle of lack of capability. The may attempt to fix this through trial and error, or choose not to proceed. This forms part of their progress decision process.

Progress decision process

We deliberately describe these as attempts because progress is not guaranteed. Seekers may fail or decide to not start, or abandon the attempt altogether.

A Seeker’s decision process is shaped by ongoing phenomenological judgements of progress – how they perceive progress potential and progress reached – and their approach to lack of capabilities progress hurdle.

There are three common reasons a seeker might abandon an attempt:

- replacement – they’ve found, what they judge, a better way to progress

- disenchantment – they’re not happy with progress reached and/or remaining progress potential

- phenomenological – they’ve just decided not to continue for reasons best known to them

Failure to progress typically stems from one of two causes: either the necessary capabilities were unavailable, or the resources at hand – carrying the necessary resources – could not be effectively integrated.

When they lack capability, Seeker’s often turn to progress propositions to attempt progress.

Progress propositions: help progress to be made

Not all Seekers are equipped to overcome capability hurdles on their own. Some do, through trial and error, persistence, or systematic experimentation. Occasionally, those who succeed turn around and offer their newly acquired capabilities to others, carried by some form of resource. When they do, they shift roles: from Progress Seekers to Progress Helpers.

Their offer? A progress proposition: a bundled set of supplementary capabilities designed to help others progress.

At their core, progress propositions consist of two interlinked components:

- proposed series of progress-making activities

- progress resource mix of capability-carrying resources to integrate with to make progress

You may recognize the proposed activities in more familiar forms: processes, playbooks, instructions, checklists, recipes. The resource mix, on the other hand, contains the missing capabilities the Seeker needs to reach the proposition’s progress sought.

Expanding the pool of capabilities

Progress propositions expand the total pool of capabilities available to Seekers. They do so by embedding supplementary capabilities into a proposition-specific resource mix.

A key insight is that resources with equivalent capabilities can be swapped within the mix. These swaps may not be one-to-one, but they allow for powerful innovation in how propositions are constructed.

The additional hurdles

Every progress proposition introduces new friction in the form of additional progress hurdles. Each of which the Helper should try and minimise in the eye of the Seeker.

- Adoptability – can the Seeker envision themselves using this proposition? (think Rogers’ classic adoption curve factors.)

- Resistance – will they hesitate or resist the proposition, even if the progress potential is clear?

- Lack of confidence – do they trust the Helper and believe in the proposition? (this is where branding becomes essential.)

- Continuum misalignment – does the proposition relieve or enable to the degree the Seeker desires? Misalignment here can stall uptake.

- Inequitable effort exchange – for simplicity: does it cost too much? (but effort exchange is the underlying concept, and door opener to business model innovation)

Progress proposition are a fertile ground for innovation: improving progress, reducing hurdles etc. In fact, we find many levers that drive innovation and when we align propositions for sales.

Progress propositions are fertile ground for innovation. They not only help Seekers overcome capability gaps but also reveal the subtle frictions that block adoption. By aligning existing propositions, and innovating, to both amplify progress and minimise hurdles, businesses address the sales, innovation and growth problems.

Our final context completes the progress economy.

The Service Exchange Context: the economics

Lastly, we have the context that wraps up the progress economy: the service exchange context.

Why does a Progress Helper offer a proposition in the first place? Because they’re a Seeker too. They are pursuing their own progress, and in doing so, require capabilities they don’t possess. The underlying truth is this: we don’t exchange value – we exchange service. That is, we apply our capabilities to benefit others, and expect others to do the same for us. I help you. You help me.

Service exchange isn’t transactional in the traditional sense. It’s relational and contextual. We look not for equality, but for equity. A perception that what’s being exchanged feels fair in effort. If I apply significant effort to help you make progress, I expect something of comparable weight in return. That return might not be immediate or even from the same person. But it must feel fair.

Effort – or more precisely, the perception of effort – is how we measure this fairness. Equitable exchange can span multiple interactions, over time and across parties, but must still feel balanced to those involved.

Although, this direct exchange is often hidden. Service can be frozen in goods. Service exchange can be transitive – you help me, but I want someone else’s help, who want yet someone else’s help and so on.

We observe service credits enabling such exchanges as well as mediating size and temporal differences. Money has been a very successful implementation of service credits.

This context is where we find the opportunities for business model innovation (hiring, subscription, subsidised, and more)

Editing below here

Let’s progress together through discussion…