We innovate in order to make better progress; either for ourselves or to get help making progress we seek through service exchange

Editing below here

What we’re thinking

There are many commonly cited reasons for why we innovate. Most revolve around creating value or generating cash.

The progress economy reframes that question. We innovate to make better progress – from a progress origin to a progress sought – and, in doing so, improve well-being. We also make a simple observation: the capabilities required to make progress are unevenly distributed across economic actors.

Why this matters

That imbalance creates the conditions for service exchange to become the basic unit of economic activity. We help others make progress in order to receive help making our own (often indirectly and typically mediated by service credits).

This dynamic explains why individuals who innovate for themselves are motivated to offer those innovations to others, and why other actors innovate deliberately focussing on particular progress journeys.

It also gives a concrete explanation for Drucker’s dictum: innovate or die.

As Seekers make progress across all aspects of their lives, they accumulate capabilities (shifting their progress origin) and raise their expectations (stretching their progress sought). If your proposition fails to evolve (innovate) in step with those moving targets, it becomes steadily less attractive. Service exchanges decline, relevance erodes, and eventually, the organisation dies.

Why innovate?

The answer to why we innovate is multi-layered, with innovation occurring at both the individual and firm levels.

As an Individual

Individuals – let’s exclude entrepreneurs for now – typically innovate to overcome a struggle or obstacle that stands in the way of something they want to achieve. In doing so, they might create something entirely new, repurpose what already exists, or combine existing elements in novel ways.

A Seeker might discover or create new capabilities, combine existing ones in inventive ways, or develop clever workarounds and shortcuts that make their own progress easier, faster, or more consistent. These “micro-innovations” often emerge invisibly in the real world. The teacher who designs her own grading spreadsheet, the nurse who rearranges equipment to improve patient flow, the manager who scripts a time-saving automation.

Afterwards might they seek to capture value from their innovation, often through selling it (an example of the value-in-exchange model in action).

What’s particularly revealing is how individuals describe their motivation. When asked why they innovated, most speak about solving a problem, or achieving something they previously couldn’t, rather than about creating value. To me this is close to the progress economy lens. It’s a distinction we tend to lose when shifting the conversation to why firms innovate, even though the underlying drive should remains the same.

As an organisation: to create a customer

Drucker tells us that we innovate to create a customer. That is, to elicit an exchange of value – cash for products. We create products, services, and processes that we believe hold better value for our customers than those our competitors, including the customer, can.

because the purpose of a business is to create a customer, the business enterprise has two – and only two – basic functions: marketing and innovation

p. drucker

Defining “better” and “value” initially feels easy, and comforting, but , as we’ll see, is actually challenging.

In theory, marketing identifies customer needs; innovation creates novel solutions to meet those, and marketing then promotes the messaging that our novel solutions best fit your needs. Which is why Drucker sees those as the two basic functions of a business (everything else is a cost).

However, consider your own innovation activities. How often is the marketing input missing? Or that input steered by product features. Henry Ford’s comment about asking customers what they want would have resulted in looking only for faster horses comes to mind. Similarly, Levitt’s marketing myopia urges us to understand customers wanting a quarter-inch hole rather than a quarter-inch drill; to which Christensen observes that all marketing managers talk about this, but then push for a better drill.

Sometimes we run with the thought that innovation is creativity that comes from employees. It can which can have success, but is not world changing)?

I’ll save the discussion on how hard value is to define until section 2 of this article. For now, let’s observe that we tradtionally believe innovation embeds additional value into products, which is then monetised through higher prices or greater volume (depending upon your positioning relating to Porter’s strategy).

McKinsey reflect that by noting 84% of executives see innovation as important to growth, but that statistic only scratches the surface.

84% of executives see innovation as important to growth

McKinsey

Linked with creating a customer, firms also have a survival imperative.

As an entrepreneur

Successful individual entrepreneurs sit in-between why an individual and an organisation innovate.

They are often driven by solving a problem (enabling progress) like an individual, but they are also driven by value-in-exchange, and gaining a customer. This can blind them to the usefulness of their innovation – just see the many examples on Shark’s Tank / Dragon’s Den; or your own innovation competitions.

Innovate or Die

Whilst creating a customer partly explains why organisations innovate, Drucker also gives us a warning underscoring an urgency: innovate or die.

innovate or die

p. drucker

We have seen this play out many times.

Blockbusters failed to innovate its business model, clinging to charging late fees while Netflix grew, overtook and outlives them.

Kodak invented digital photography but failed to realign its propositions around customers’ emerging need: instant, shareable images rather than printed photos. The result was catastrophic. Kodak lost its dominant position and filed for bankruptcy, despite holding the very technology (digital cameras, photo sharing site) that shaped the future.

The same pattern plays out in B2B markets. Many traditional ERP vendors were slow to respond to the shift toward cloud-based solutions that offered more flexible, scalable, and lower-maintenance ways for businesses to make progress. SaaS challengers rapidly captured market share, leaving incumbents scrambling to reinvent their propositions – often at far greater cost than if they had acted earlier.

Though this does not mean you must be always be first to market. Apple has been a strong pointer that being a fast follower is a successful playbook.

Here’s the killer point: an “adding value” definition of innovation helps us intuitively understand Drucker’s rallying call – if we’re not giving the value a customer is seeking, then they will not use our product. However, as we struggle to define value, knowing how and where to innovate in a value-in-exchange world becomes easy in retrospect, but hard in reality. Just see the cases above.

Executives face a universal truth: innovate, or risk obsolescence…yet few have the tools to understand and react to the realities of this. Share on XFor macro-growth

So, we innovate to both create customers – growth – and sustain organisational viability. This also leads to macro-growth of economies, particularly through creative destruction.

Joseph Schumpeter described this as the process by which new technologies and business models render old ones obsolete while expanding the overall economy. Each wave of innovation destroys some industries but gives rise to new ones with greater productivity and societal benefit.

Mechanical looms destroyed manual weavers livelihoods, but led to more cloth production and GDP growth; digital computers destroyed many manual roles, but their benefit also grew GDP; Generative AI destroyed…well, we’ll see.

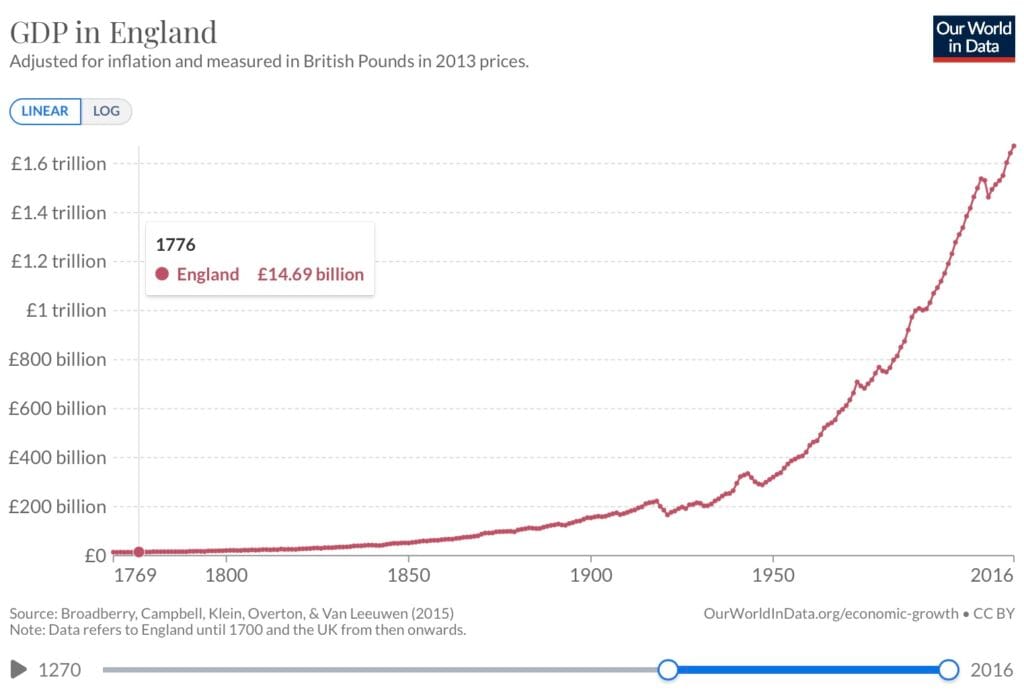

Just look at the explosive growth in England’s GDP since the time Adam Smith wrote in 1776 about the wealth of nations being driven by value-in-exchange.

Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel 2025 awarded to Joel Mokyr, Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt:

Nobel Prize Organisation

“for having explained innovation-driven economic growth“

This link between innovation and long-term economic growth continues to shape our understanding of prosperity. Indeed, the 2025 “Nobel” Prize in Economics was awarded to three researchers “for having explained innovation-driven economic growth,” recognising that the cumulative effects of innovation, across firms, industries, and nations, are the foundation of modern economic advancement.

However, Brusoni, Cefis, and Orsenigo point out that drawing a link between successful innovation and GDP growth i treated as a truism in their 2006 paper “Innovate or Die? A critical review of the literature on innovation and performance“. Though they found little empirical evidence of this. This may reflect a difference between creative destruction and day-day innovation.

To attract effort exchange

At its heart, innovation is the act of finding and applying new capabilities to make better progress. Either improving the way progress is already made, or enabling progress that was previously impossible.

In its simplest form, innovation helps us:

- existing progress better – a sharper knife makes cutting easier and more precise

- better progress than before – a food processor allows slicing, dicing, and blending at speed and scale that were once impractical.

In this way, both Seekers and Helpers can innovate. A Seeker might discover or create new capabilities, combine existing ones in inventive ways, or develop clever workarounds and shortcuts that make their own progress easier, faster, or more consistent. These “micro-innovations” often emerge invisibly in the real world. The teacher who designs her own grading spreadsheet, the nurse who rearranges equipment to improve patient flow, the manager who scripts a time-saving automation. Each represents progress made possible by ingenuity under constraint.

As the familiar Progress Economy story reminds us, Seekers often face a lack of capability – skills, knowledge, time. physical capabilities like strength, etc; or even the capability to innovate or execute innovations – when attempting progress.

Enter Progress Helpers.

Progress Helpers offer to supplement or extend Seekers’ capabilities, helping them move from a progress origin to a progress offered state. A Progress Helper could be an organisation, a platform, or even another individual – anyone offering capabilities that make it easier for a Seeker to achieve their desired progress.

Importantly, Progress Helpers are themselves Seekers of progress. They offer propositions in order to undertake service exchange for help making progress they seek that they lack capability to undertake.

This exchange can be direct — as in a traditional service transaction: you help me and I help you — or more likely indirect, mediated through what we might call transferable service credits. The most successful and universal form of such credits, of course, is money. It allows for the asynchronous, multi-party exchange of progress-making capability across time, scale, and context.

From this perspective, innovation becomes an act of mutual progress-making. A Helper’s incentive to innovate is clear. The Helper whose proposition best helps a Seeker progress – moving them closest to their progress sought from their progress origin, with the lowest progress hurdles and the earliest value recognition – will gain the greatest share of service exchange.

This reframes Peter Drucker’s classic observation that “the purpose of business is to create a customer.” In the Progress Economy, we restate it as:

The purpose of a Progress Helper is to gain help making progress relevant to themselves, through the maximum possible service exchange (direct or indirect; in number or magnitude). As such, the Helper has 3 – and only 3 – functions: marketing, innovation and execution

To achieve that, every organisation must perform three interdependent functions:

- Marketing — understanding which Seekers to help, and what progress they seek.

- Innovation — creating new or improved ways to enable that progress.

- Execution — delivering those capabilities effectively, reliably, and sustainably.

WHY INNOVATE? INNOVATE OR DIE, EXPLAINED

Peter Drucker’s famous warning of “innovate or die” has long felt intuitive. The Progress Economy helps us see why it holds true.

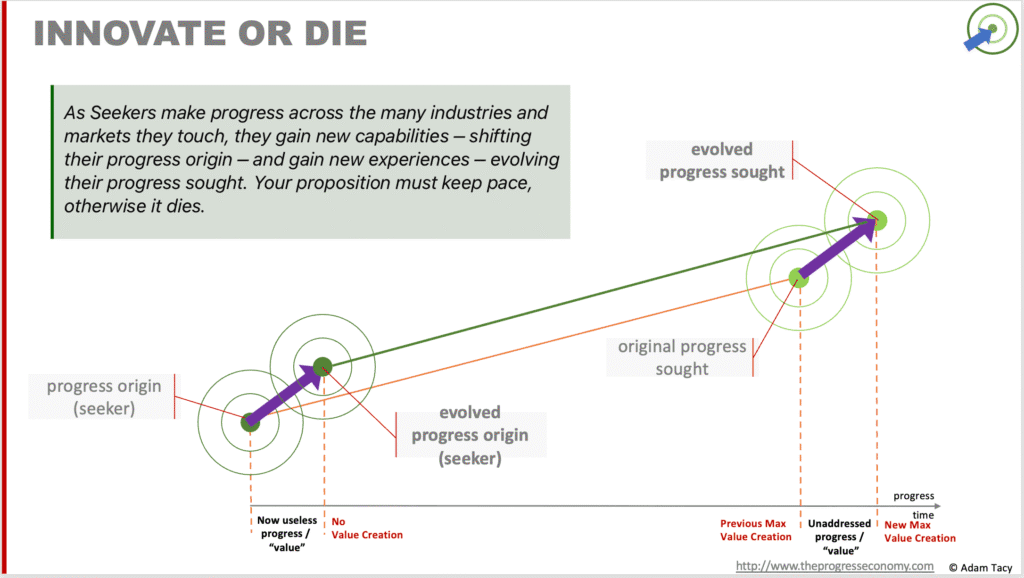

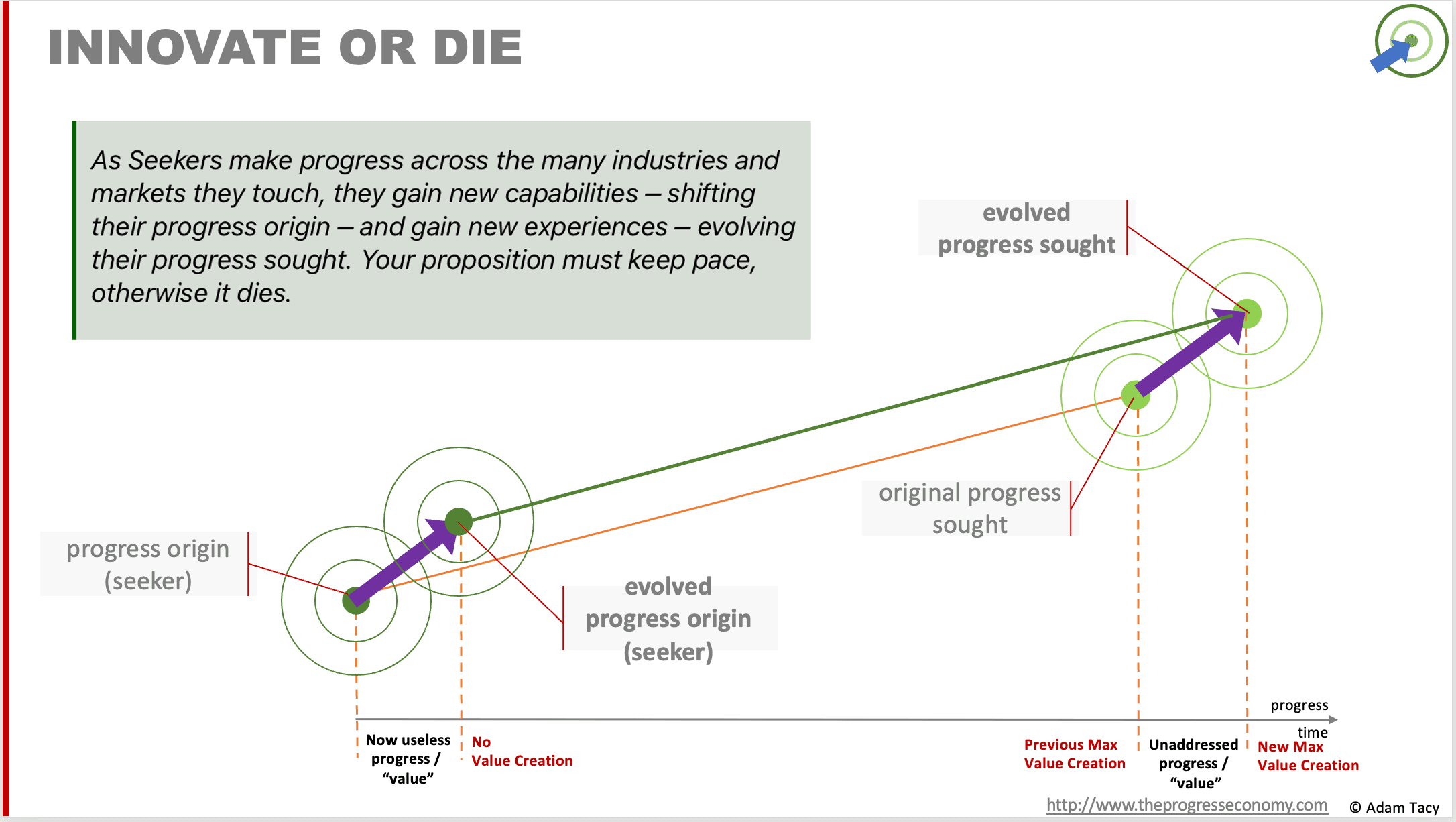

Seekers are not static. They are continually making progress attempts – not just in your market or industry, but across all aspects of their lives. In doing so, they gain new capabilities, experiences, and expectations. As a result, a Seeker’s progress origin (where they start from) and progress sought (the more desirable state they are trying to reach) are constantly evolving.

It looks like the following progress diagram.

Remember that value, in the progress economy, is a set of progress comparisons. Potential value, for example, includes the Seeker’s comparisons of progress sought and progress offered, as well as their origin compared to the proposition’s origin. As the Seeker’s states evolve, the proposition is seen as helping make progress less and less.

When that happens, service exchange declines. If left unchecked, your proposition’s relevance fades away. The Helper needs to evolve their proposition. That is, they need to innovate, or die.

We see this pattern everywhere. What once felt like breakthrough progress — the high street bank branch, the compact disc, the business-class lounge — becomes unremarkable once Seekers learn new ways to make better progress. Challenger banks, streaming services, and shared workspaces didn’t just offer cheaper or more convenient options; they matched the new shape of Seeker progress more closely.

Progress sought is also influenced by Externalities. Regulators, institutions, and societal forces continuously change, shaping what is considered safe, ethical, and acceptable. Their influence is injected directly into a Seeker’s progress sought, altering the lack of capability progress hurdle, driving the need to evolve progress propositions.

So Drucker’s phrase isn’t a threat; it’s a natural law. The Progress Economy explains it not as a matter of will or competition, but as a matter of alignment. Innovation is the act of staying in sync with, or ahead of, the evolving progress of those you serve.

Let’s progress together through discussion…