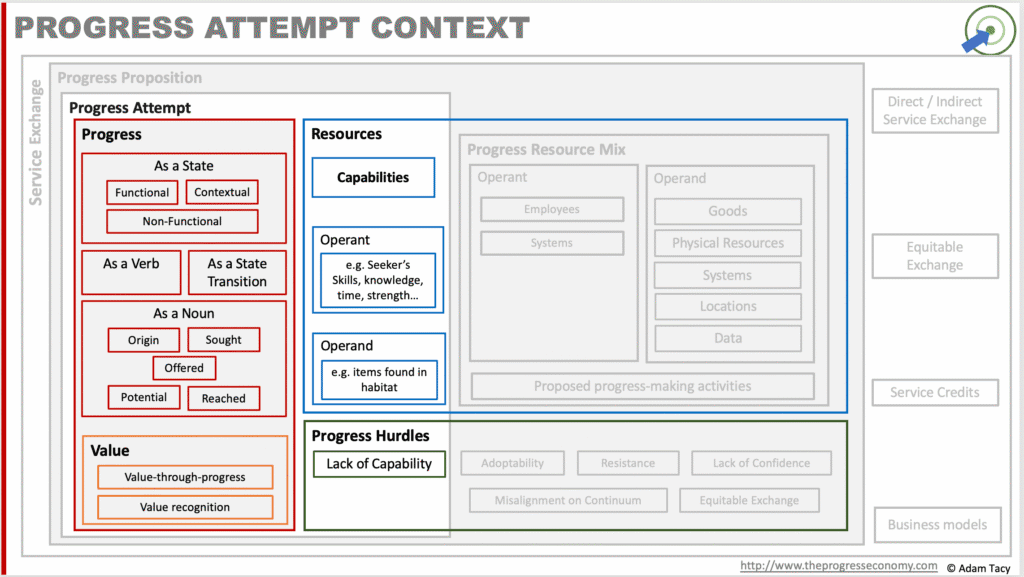

Seekers attempt to make progress by integrating capability-carrying resources in a series of progress-making activities. If they lack the capabilities, progress is affected

What we’re thinking

Progress attempts are the executional view of progress journeys – a deeper level of understanding that leads to better innovation and sales.

They give us the insight on how a Seeker attempts to get from their progress origin to their progress sought through a series of progress-making activities. Each activity is a resource integration between two or more capability-carrying resources. One of which must be operant – a resource that acts on other resources to make progress.

We deliberately say attempt as they may not succeed. Lacking capability is the foundational hurdle to making progress. Facing this hurdle, Seekers may try to generate capabilities themselves through trial and error. More often, they will engage the supplementary capabilities offered by progress propositions

We are now in a position to explore a Seeker’s progress decision process. It is one of repeated progress comparisons (value) and judgements of the lack of competence progress hurdle. An attempt either doesn’t start, succeeds in reaching progress sought (where maximum value for the Seeker has emerged), or is abandoned along the way due to a discontinuance (replacement, disenchantment, or phenomenological).

Understanding progress attempts informs us that Seeker’s innovation revolves around them creating/improving capabilities, including the progress-making activities, in order to improve how they currently make progress and/or how to get closer to their progress sought.

Progress attempts: Moving to progress sought

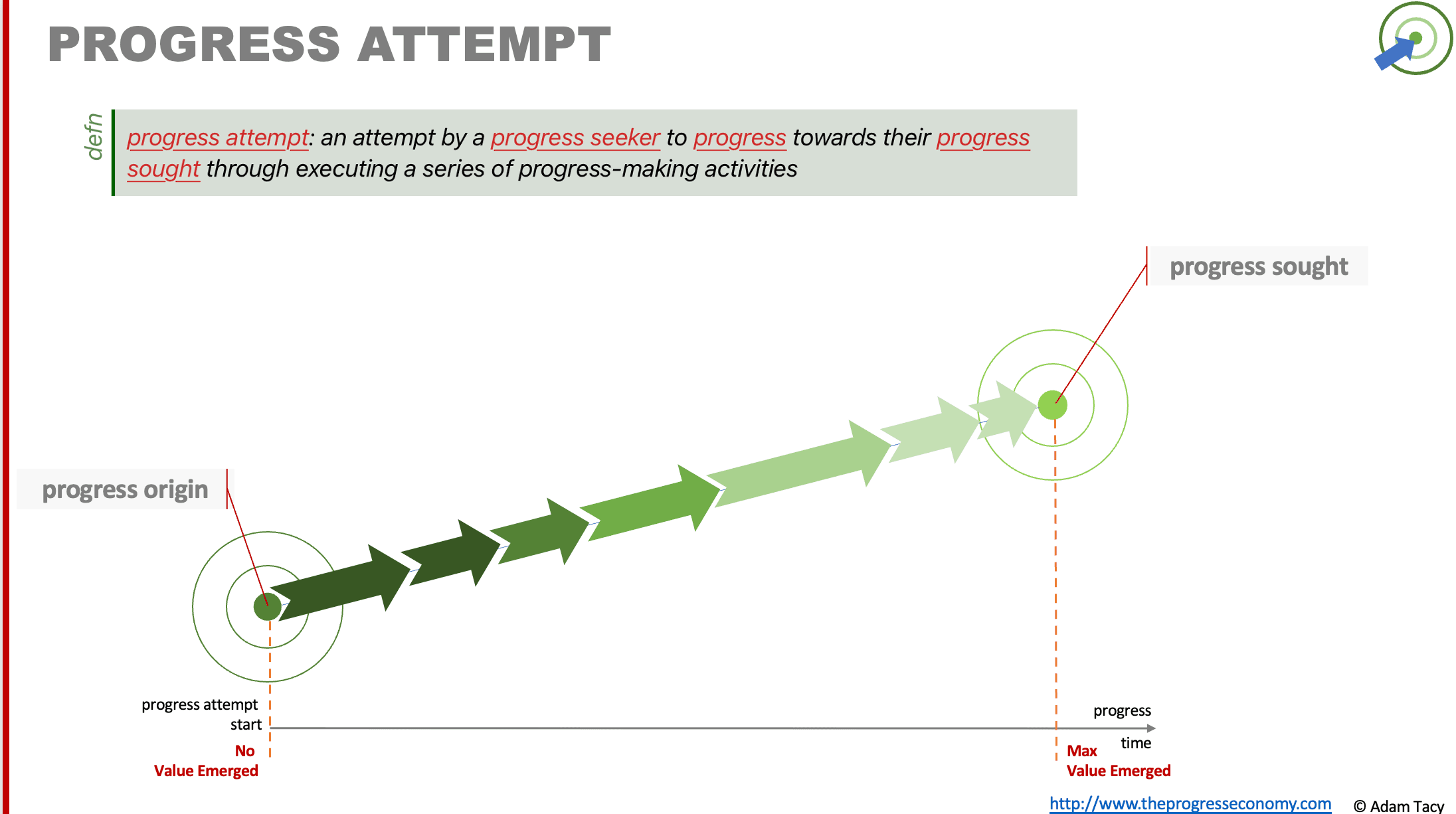

progress attempt: an attempt by a progress seeker to progress towards their progress sought through executing a series of progress-making activities

Think of a progress attempt as the execution view of progress as a verb. It is how a progress Seeker attempts to move to their more desired state of progress sought from their progress origin.

Payne et al establish the seeds of this:

The customer’s value creation process can be defined as a series of activities performed by the customer to achieve a particular goal.

Payne, A. F., Storbacka, K., and Frow, P. (2006) “Managing the co-creation of value”

Through deliberate execution of a series of progress-making activities – each one integrating two or more capability-carrying resources – a Seeker attempts to make progress on their progress journey. When executed successfully, each activity moves the Seeker a step closer to their progress sought.

Let’s update our progress diagram to reflect this.

Updating the Progress Diagram

We can take our progress diagram from progress as a verb and update it to show progress is a series of steps (progress-making activities).

The same progress origin and progress sought apply, with value emerging as progress is made – none at the origin, and maximum value (for the Seeker) upon reaching their progress sought.

Since each progress-making activity can take a different amount of time and deliver varying degrees of progress, we conceptualise the steps as arrows of differing length.

There’s an important point to cover: these are attempts, not guarantees of progress.

Attempts not guarantees

We use the word attempt purposefully. Progress isn’t guaranteed. Sometimes seekers fail when executing an activity. A Seeker may misapply capabilities or, more often, they lack needed capabilities. These capabilities include skills, knowledge, availability (time), strength and so on (or at a more organisation level we might talk of Sales, accounting, or R&D capabilities).

And let’s remember that a Seeker is trying to make progress with everything in their life. However, we usually concentrate on one particular aspect at a time – a Seeker phenomenologically decides what that is, based on what’s important to them at that point in time, and if they feel they can make progress.

When a Seeker lacks some or all of the necessary capabilities, they face the foundational progress hurdle we call the lack of capability. This directly affects their ability to make progress.

Interestingly, as we’ll see later, knowledge of, and skills to execute, the series of progress-making activities required are capabilities that the Seeker may lack.

When this lack of capability hurdle arises, the seeker faces a choice: develop the missing capability independently – usually by trial and error, accessing resources in their environment, or observing others and copying – or engage a progress proposition. These propositions offer supplementary capabilities, packaged within a specific resource mix and accompanied by a proposed sequence of progress-making activities. Progress becomes a joint endeavour… but that is something we’ll explore in the next context layer.

Relationship to service

Since the Progress Economy builds on Service-Dominant Logic, it’s natural for us to discuss how progress attempts relate to the concept of service

It might seem strange to consider a progress attempt as service (singular), but they are acts of self-service. Thinking this way helps set the scene when we later build progress attempts into attempts with progress propositions.

Let’s start with Vargo and Lusch’s definition of service:

service: the application of competences (knowledge and skills) for the benefit of another party

Vargo & Lusch (2008) “From Goods to Service(s): Divergences and Convergences of Logics”

For our progress economy definition, we need to substitute competences for capabilities (which also widens the scope from just knowledge and skills) and say it is for the “benefit of oneself or another party”. Therefore, we define service (singular) as:

service: the application of capabilities for the benefit of oneself or another party

You probably wonder why we say service (singular). We want to distinguish between this and services (plural) which is often used in comparison to goods. As a plural, services refers to a unit of output; in the singular, it is the process we are interested in (see more here: services vs service).

Now it makes sense, right? We apply our capabilities to benefit ourself. Maybe we tattoo ourselves (a mainly non-functional progress sought) or we self medicate, or create a vessel out of wood and use that vessel to carry fresh drinking water. This usefully brings the role of goods into view.

Role of goods

What do goods do? They freeze service – the application of capabilities – so it can be distributed in time and location. A Seeker then unfreezes that service during acts of resource integration.

In our progress attempts context, goods are limited to what a Seeker discovers or creates from their natural environment. Think of a Seeker using their own knowledge and skills to carve a bowl from wood. That bowl embodies – freezes – that knowledge of holding and transporting liquid. Each time the Seeker uses it to collect water from a stream, they are unfreezing those embedded capabilities.

It’s certainly reasonable to argue that goods acquired through progress attempts that have engaged progress propositions could also be included. However, for clarity and conceptual discipline, we’ll draw a line here: such goods fall under propositions, even if there’s no active Helper involved at that moment. In effect, re-using those goods is still engaging a proposition.

Another implication of this framing is that goods, at this level, are almost always physical. Without access to more advanced goods, it’s difficult – if not impossible – for a Seeker to create digital goods.

We’ll revisit the role of goods in more depth when we examine progress attempts in richer contexts. But even this minimalist landscape reveals a core insight: without Helpers and their propositions, a Seeker’s ability to make meaningful progress is sharply constrained.

Talking of context, let’s explore where progress attempts fit.

Putting progress attempts in the strategic context

Progress attempts build directly on the broader context of progress (and value).

We introduce three critical operational aspect: capabilities, carried by resources, progress-making activities (which are acts of resource integration) and the progress hurdle that is foundational: lack of capability.

Resources fall into two categories: operant resources (those that act on other resources to make progress) and operand resources (those that must be acted upon for progress to occur).

This framing introduces not only a mechanism for understanding progress execution (without external help), but also a diagnostic for identifying capability gaps that shine a light on the foundation progress hurdle (a lack of capability) and the opportunity space for helping.

Now we’ll explore the detailed mechanics of making progress, starting with where the Seeker starts how their progress origin and sought usually evolve over time.

Progress origin and sought: evolving over time

We inherit progress origin from our exploration of progress as a verb, where we saw it is the Seeker’s starting point. Similarly, we inherit progress sought as the Seeker’s more desired state. For clarity and manageability of analysis, we noted that we typically isolate specific aspects of progress at a time, though we need to be aware other aspects may sometimes interconnect or even conflict.

Now, as we shift focus to progress attempts, we’ll recognise that both a Seeker’s origin and progress sought often evolve. Seekers constantly engage in progress attempts across all areas of their life. In doing so, they accumulate new capabilities, that can change their origin, and can often cause them to stretch their progress sought.

In short: every attempt reshapes the map. Progress isn’t static; it adapts with experience, exposure, and ambition. And that has strategic implications for how we support, enable, and anticipate a Seeker’s evolving needs.

Progress between progress origin and progress sought is made through progress-making activities.

Progress-making activities

As we saw from Payne et al, value creation (making progress in our view) comes from a customer performing a series of activities to reach their goal.

The customer’s value creation process can be defined as a series of activities performed by the customer to achieve a particular goal.

Payne, A. F., Storbacka, K., and Frow, P. (2006) “Managing the co-creation of value”

Seekers make progress one step at a time. Each step – a progress-making activity – represents a purposeful integration of capability-carrying resources.

progress-making activity: A resource integration that increases a seeker’s progress reached towards progress sought.

Consider a basic example: a Seeker (a resource) wants to grow vegetables for nourishment (functional component of progress sought). They apply their skills and knowledge (capabilities) to integrate seeds, soil, water, sunlight, and time (other resources). The following could be the series of progress-making activities they undertake:

- prepare seeds

- prepare soil

- sow seeds

- water the growing plants

- weed the surrounding area to remove competing plants

- check for maturity

- harvest vegetable

Each activity is a unit of progress, and each requires application of capability through resource integration. There’s a couple of concepts we should look into more.

Understanding capabilities and resources

Capabilities power progress. Resources carry those capabilities.

For a simple Seeker, like an individual, capabilities are skills, knowledge, availability, and physical attributes such as strength. The person themself is the resource. For example, when sowing seeds, we apply our knowledge of the correct depth, soil type, and coverage, along with a measure of physical strength to make the hole and cover it.

For a more complex Seeker, such as an organisation, capabilities tend to operate at a higher level of abstraction. We speak of innovation, learning, marketing, or R&D as capabilities. These are often distributed across systems, teams, and processes – still capabilities, just carried by more sophisticated resources.

Not all capabilities originate from the Seeker. Some are external, like the ability to generate power or transport materials. These might be carried by wind, water, or other natural resources.

These capabilities must be applied in order to make progress. That application happens through resource integration: the deliberate combination and use of resources to unlock their embedded capabilities.

What is resource Integration

Making progress requires that the capabilities carried by a resource be applied. This act is known as resource integration. For example, as a Seeker (a resource), you apply your capabilities, such as skills or knowledge, to another resource in order to leverage its capabilities and move closer to your progress sought.

This leads us to a useful distinction. Some resources do something. Others have something done to them. We refer to the former as operant resources and the latter as operand resources.

Operant Resource

acts on other resources resulting in progress being made

Operand Resource

needs to be acted upon for progress to be made

Progress happens when an operant resource successfully integrates with operand or other operant resources. The Seeker moves closer to their desired state.

resource integration: an operant resource applies their capabilities on one or more operand or other operant resources to take a step forwardstowards a Seeker’s progress sought

In solo progress attempts, the Seeker is usually the operant resource. This is something we relax when looking at progress propositions (there it could by a system, an employee of the Helper, or a combination of).

There are also non-human operant resources. Solar energy and wind, for example, can act on other resources without human intervention. In the case of growing vegetables, even the seed or plant itself can be viewed as an operant resource—integrating water, nutrients, CO₂, and sunlight to generate physical growth (but let’s not overcomplicate a simple illustration).

And occasionally, the Seeker might be both the operant and operand resource. Such as when applying makeup, self-tattooing, or reading. In these cases, the Seeker both acts and is acted upon.

Defining the activities

Sometimes, Seekers instinctively know which progress-making activities are required. They draw on past experience, observation of others, or analogical reasoning. Not knowing the activities , or the correct sequencing, is a lack of capability. The Seeker must discover what works through experimentation and trial and error (or not start the attempt). Sometimes, it’s a blend: they begin with a rough idea and iterate their way forward.

In everyday life, we recognise these series of activities in more familiar forms: action lists, plans, recipes, checklists, experiment designs, and so on. Some are written down; others live informally in our minds.

Think of baking a cake. The recipe contains the knowledge, but it can’t act on anything. It’s an operand resource carrying knowledge. Only when the Seeker applies their skill – integrating ingredients and applying the recipe – that progress is made and a cake is baked.

It is from successfully executing these progress-making activities that progress is made, and our perception of value emerges.

Further understanding value

We established, when looking at progress as a verb, that the concept we call value emerges from a set of phenomenological progress comparisons. There are three readily identifiable values:

- potential value – the Seeker’s phenomenological assessment of how close they believe they can get (potential progress) to their progress sought

- emerged value – their phenomenological assessment of how far they’ve already come – progress reached versus progress sought- which we conceptually see as increasing linearly along the journey

- recognised value – the meaningful value to a Seeker based on their recognition approach

These value comparisons cut across the three dimensions of progress – functional, non-functional, and contextual – which helps explain the many different types of “value” that exist in the business and marketing lexicon: use value, identity value, social value, symbolic value, hedonic value, and more.

Karababa and Kjeldgaard, writing in “Value in Marketing: Toward Sociocultural Perspectives” (2013), observed that these terms are often used without a coherent conceptual foundation. The Progress Economy provides that missing structure. It gives us a clear, unified lens through which to define, measure, and act on value – not as a feature of offerings, but as a lived, evolving judgment in the mind of the Seeker.

Now we are also in a position to further explore how Seeker’s turn emerged value into something that is meaningful to them – by recognising it.

Seekers need to recognise emerged value

When does the value that emerges through progress become meaningful to a Seeker?

Here an example helps our thinking. Let’s say the functional part of our progress journey is the simplistic “travel 100km from where I am”. How valuable is reaching 80km to the Seeker?

The answer is, it depends on the seeker, that particular attempt, and the non-functional and contextual progress elements.

For some seekers, every kilometre is meaningful as they are getting closer to their progress sought. If you have no other constraints, you’d likely recognise each kilometre travelled as value to you.

But what if you have to reach 100km by a set time, and have only reached 80km. Now that 80km has no value to you – it’s no better than having not started (perhaps worse if the attempt diverted you from other progress you could have attempted instead).

We say that a seeker needs to recognise value for it to be meaningful to them. This is a phenomenological decision they make. It’s akin to revenue recognition for any accountants out there (where revenue is generated continuously, but is only recognised in accounts for firm when certain conditions are met).

And there are many schemes the Seeker may apply. For example, and as shown in the above diagram, they may recognise value immediately, at regular intervals, at the end of each progress-making activity, or only upon reaching their progress sought.

This distinction is central to understanding and designing for progress in real-world contexts. It shifts our focus from simply creating output to ensuring meaningful, recognised outcomes.

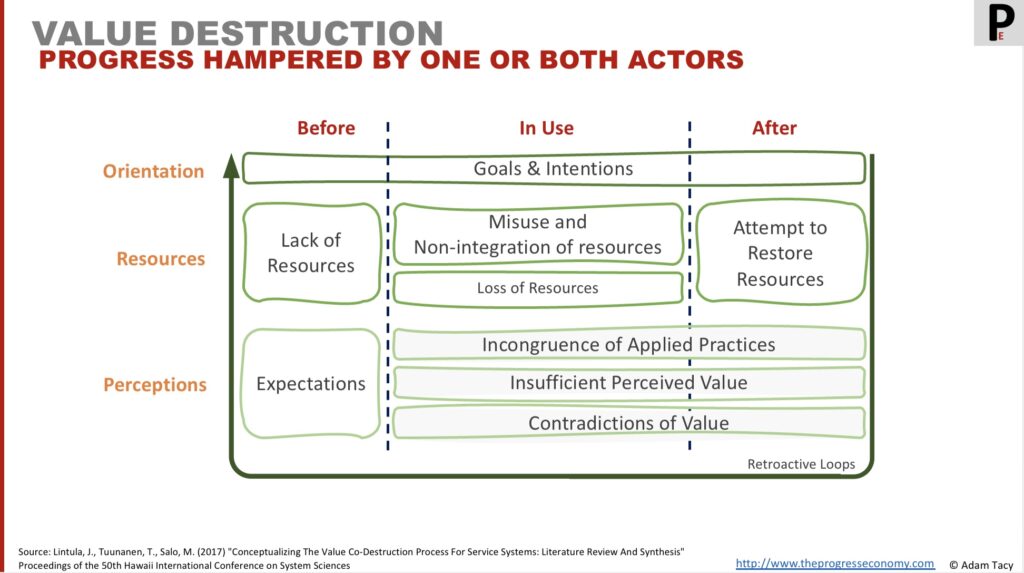

Destroying value

Value can be destroyed. But we need to understand what we mean by this.

Traditional value-in-exchange models view value as something embedded in a product during production, then transferred to the customer at the point of sale. It equates to the highest price someone is willing to pay. Take a car: manufacturing is thought to embed value into it; purchasing transfers that value to the customer. But some value is destroyed the moment the customer drives away from the dealer, and continues to be used-up as they drive the car around. The customer may try to restore it through servicing, or recover some of it through resale.

This legacy model contains two major blind spots.

First, it gives the manufacturer little reason to stay involved beyond the point of exchange, so value restoration and recovery often happen without support, feedback, or strategic intent. Second, it encourages an exchange-first mindset, making it harder to support alternative models like leasing, sharing, or other ways to enable progress sought.

Progress-forward thinking shifts the conversation. In a value-through-progress model, there is no embedded value to exchange. Value isn’t transferred, it emerges as the Seeker successfully executes progress-making activities.

So how is value destroyed in this model? Quite simply: when progress breaks down.

Value destruction occurs when:

- The Seeker lacks the necessary capabilities

- Capabilities exist but are misapplied or the resources carrying them are integrated poorly

- Resources carrying the capabilities are lost, inaccessible, unavailable, or used-up

In other words, no progress, no value.

This framework redefines value destruction—not as product depreciation or consumption, but as failure in execution. And as we’ll see in later chapters, Lintula et al.’s work on value co-destruction adds further nuance, showing how breakdowns can occur before, during, or after engaging a progress proposition.

This view opens new strategic territory: value isn’t something you ship—it’s something you enable. Preventing value destruction means designing systems and propositions that keep progress on track.

On the other hand, “misuse” of resource/capabilities might result in innovation – a better way to progress, or make better progress.

Attempting Progress: the Seeker’s decision process

Whether consciously or unconsciously, progress seekers follow a well-defined decision-making process when making a progress attempt. Understanding this process gives us a powerful lens for designing better experiences, reducing friction, and increasing conversion. But that’s for our discussion on progress propositions. It all starts with understanding the decision process of progress attempts, on which we’ll later build.

At its core, a progress attempt mirrors the dynamics of innovation adoption. It starts with a decision to begin and is sustained through a series of decisions to continue. This structure is conceptually similar to Everett Rogers’ Innovation Adoption Decision Process from Diffusion of Innovations. And that’s no coincidence. Every progress attempt is really the adoption of an innovation (the big job/little job concept of jobs to be done theory).

It’s useful to think of these decisions happening at the start of each progress-making activity. And more useful to know that they are unique and phenomenological judgements made by individual progress Seekers.

Initiate decision: Should I Start?

The seeker weighs two key factors:

- progress potential against progress sought: How closer this attempt could bring them to their desired state of progress sought.

- lack of capability hurdle: How high the hurdle is, based on the capabilities they currently lack.

If the perceived progress potential is high enough, and the lack of capability hurdle is low enough, for that individual Seeker, then they choose to begin. If not, they reject starting the attempt. But rejection isn’t permanent. Progress seekers often revisit and reassess. For example, a lack of time or energy today may no longer be an issue tomorrow. Progress is dynamic, and so are Seekers motivations.

Continuation decision: Should I continue?

Once the attempt is underway, the Seeker continues to evaluate. At natural breakpoints (typically at the end of each activity, or start of new one, depending on how you want to look at it), they reassess based on updated judgments:

- progress reached vs. expectation: Am I where I thought I’d be?

- progress potential vs. progress sought: Does the path ahead still look promising?

- revised progress sought: Has my goal shifted?

- Updated lack of capability hurdle: Do I now lack something I didn’t expect?

If the promise of progress still outweighs the friction, they continue. If not, the attempt stalls or ends in what we call a discontinuance.

Discontinuances: Why a Seeker abandons a progress attempt

There are three primary reasons seekers abandon progress attempts:

- replacement: They find a better path to progress and shift course.

- disenchantment: They lose faith in the approach – progress is too slow, difficult, or disappointing.

- phenomenological: The most human of all – they simply lose the will. “I just can’t be bothered anymore” or some other aspect of progress sought becomes more important to them

Each form of discontinuance reveals valuable insights into friction, unmet needs, and where innovation should go next.

What does success look like?

The natural assumption is that a successful attempt means reaching progress sought. And in theory, it does, because that’s where maximum value emerges for the seeker.

But reality is more nuanced. In many domains, reaching the ideal outcome is impractical, even impossible. More often, success looks like sufficient progress for now. Which is a compromise shaped by context, constraints, or shifting goals.

Ultimately, success is defined subjectively. It rests in the seeker’s own comparison of progress reached versus progress sought and whether that leaves them phenomenologically satisfied.

This subjectivity isn’t a weakness in the model. It’s a strength. It reminds us that progress (and therefore, value), is always judged in context, always in motion, and always personal.

Editing below here

Relating to innovation

Innovation is all about increasing progress judgements which we can interpret as:

- reducing the lack of capability progress hurdle

- improving capabilities

- improving the progress-making activities

- increasing the frequency of value recognition

We need to approach this with regard to the three components of progress (functional, non-functional and contextual) and in relation to the Seekers progress origin. And when I say “we” here, I mean only the Seeker, since our context here is solo attempts. They might do so through:

- using existing resources in different ways

- acquiring new resources from nature (or other progress attempts they have made)

- observing and copying other actors

- altering their progress-making steps through trial and error or deliberate planning

Admittedly, solo progress attempts are limited, but considering them lays the foundation for, and to understand, what comes next.

Seekers that successfully find ways to make progress may decide to offer their new found capabilities to others. They become a progress helper with a progress proposition.

Let’s progress together through discussion…