Beyond Value Podcast Episode:

Value is difficult to define, agree upon, and action; yet all we talk about is maximising and adding value. Join me on the journey to discover “value” is better understood as achieving benefit – and that the largest benefit comes by getting closest to the progress you seek.

What we’re thinking

What if our traditional view of value – despite its past success – is now holding us back due to several blind-spots that are increasingly impactful ? Is it quietly limiting how we innovate, sell, and generate growth?

It’s time to re-imagine what value really is – and unlock a model built for today’s challenges.

At first, we might feel value is easy to define. It’s the highest amount we are willing to pay for something. But probe deeper, and it quickly becomes slippery and abstract. Adam Smith, Karl Marx, McKinsey and many others have tried to define it, but worryingly, Grönroos still tells us “value is a ‘concept that is difficult to define’” and worse, Anderson and Narus tell us not many of us can answer simple questions about it:

“remarkably few suppliers in business markets are able to answer…” questions like “…How do you define value? Can you measure it?”

Anderson and Narus (1998) ”Business Marketing: Understand what customers value”

That’s not just an academic problem – it’s a problem for you and your customers, for your sales, innovation and growth. If we can’t define value clearly, we can’t actionably create or deliver it (whatever those mean)!

Our Proposed shift

In the Progress Economy we make a shift in our view: we seek benefits rather than value, and benefit emerges from progress (as a set of various progress comparisons).

We are all looking to make progress – to a more desired state – with everything in life. We get maximum benefit when we’re reached our progress sought.

Seen this way:

- Sales is about aligning offerings to enable real progress

- innovation is discovering and delivering better ways to make progress

- Sales may lead to innovation; innovation needs sales

To arrive at this conclusion, we’ll examine the two common views of value today:

- value-in-exchange – where value is embedded in products and exchanged in transaction (this is our traditional view, and has become known as goods-dominant logic). It has numerous blind-spots that are increasingly impactful on innovation and growth

- value-in-use – value only emerges as products are used (a service-dominant logic view). It offers to address value-in-exchange blind-spots, but there are lingering issues with making it actionable

- benefits-through-progress – our model that evolves value-in-use to give us the necessary terminology to build an actionable operating system for the economy and operationalise innovation/sales moving them from competing with luck, to more systematic and successful activities

Looking at Value

Let’s start by thinking value. I believe our traditional view is holding us back. Our assumptions about who creates value, how it’s created, and when it emerges, shape how we sell, how we innovate, and how we grow.

If I asked you, “What is value?”, what comes to mind?

For many of us, it’s tied to physical or digital objects we own. Take my car: I see it as valuable. The bus or taxi? For me, less so; even if they get me to the same place as my car. Why is that?

It’s the way we’ve been taught to see the world. Formal education, business training, and day-to-day experience push us to equate value with ownership, price, and exchange. We pay a significant sum for a car; we pay a small fee for a bus ticket. So we tend to see the car as valuable and the bus as less so.

Of course, your perspective might be different f you don’t have a car and the bus is your only possible form of transport. Or if you are the owner of the bus/taxi.

The dictionary view

Merriam-Webster define value is both a noun and a verb:

https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/value

- noun:

- the monetary worth of something

- a fair return or equivalent in goods, services, or money for something exchanged

- relative worth, utility, or importance

- something intrinsically valuable or desirable

- verb:

- to consider or rate highly

- to estimate or assign the monetary worth of

- to rate or scale in usefulness, importance, or general worth

Generally we are talking about how much money we can get in return for something (and assuming that something holds some value). This is the value-in-exchange model. It’s something that has quite some history.

The Historical Experts’ view

Adam Smith drew out a classification of value in his seminal Wealth of Nations in 1776. He saw “value in exchange” (power of purchasing) and “value in use” (the utility of an object).

The word value, it is to be observed, has two different meanings, and sometimes expresses the utility of some particular object, and sometimes the power of purchasing other goods which the possession of that object conveys. The one may be called ‘value in use’ the other, ‘value in exchange’.

Adam Smith (1776) “Wealth of Nations”

The things which have the greatest value in use have frequently little or no value in exchange; and, on the contrary, those which have the greatest value in exchange have frequently little or no value in use.

Nothing is more useful that water: but it will purchase scarce anything; scarce anything can be had in exchange for it.

A diamond, on the contrary, has scarce any value in use; but a great quantity of other goods may frequently be had in exchange for it.

Karl Marx built on this, distinguishing between worth (value in use) and value (exchange value):

in English writers of the 17th century we frequently find worth in the sense of value in use, and value in the sense of exchange-value.

K Marx (1886) “Capital: Vol 1“

In the end, Adam Smith settled on seeing value-in-exchange as the predominant model driving wealth growth in a nation. In his time, manufacturing was driving wealth and so he naturally saw that as productive labour. On the other hand, services – such as maids, housekeepers, butlers etc – were seen as unproductive labour (to GDP growth).

Since then, and over time, we’ve become anchored to this exchange view, especially in business. McKinsey put it succinctly:

A product’s value to customers is, simply, the greatest amount of money they would pay for it.

Golub, H., and Henry, J. (1981) “Market strategy and the price-value model” via “Delivering value to customers”, McKinsey (2000)

This view dominates boardrooms and pricing strategies today. The dictionary reinforces it: value, the monetary worth of something.

But defining an actionable definition of value – one we can find levers and tools to drive innovation, sales, and growth, turns out to be far harder than these simplistic definitions.

Value is difficult to define

Move beyond textbook definitions, and you’ll find many experts agreeing: value is slippery. Grönroos tells us value is a “concept that is difficult to define.”

value is a “concept that is difficult to define”

Grönroos (2008) ”Service logic revisited: who creates value? And who co-creates?”

More worryingly, Anderson and Narus found that we struggle to answer basic questions like, “How do you define value?” or “Can you measure it?”:

“remarkably few suppliers in business markets are able to answer…” questions like “…How do you define value? Can you measure it?”

Anderson and Narus (1998) ”Business Marketing: Understand what customers value”

This is not a minor problem. Almost every business claims it is trying to maximise value. But if we can’t clearly define it, how can we reliably create, deliver, or maximise it?

The challenge deepens. Karababa and Kjeldgaard identified a long list of competing value concepts, each “lacking a definitive basis”, including:

…use value, exchange value, aesthetic value, identity value, instrumental value, economic value, social values, shareholder value, symbolic value, functional value, utilitarian value, hedonic value, perceived value, community values, emotional value, expected value, and brand value…

Karababe, E. and Kjeldgaard, D. (2013) “Value in Marketing: Toward Sociocultural Perspectives”

…are examples of different notions of value, which are frequently used without having an explicit conceptual understanding in marketing and consumer research.

Across marketing, strategy, consumer research, innovation, sales, and more, we often use these terms without a shared, rigorous understanding. The result: we talk about value as if it’s obvious – when in fact, it’s anything but.

Why this is a problem

Our beliefs about value drive how we sell, how we design propositions, and how we innovate.

If we believe value is embedded during successive manufacturing steps with a focus on making exchanges, then we optimise for that. And that mindset has indeed powered centuries of growth. You only have to look at GDP growth since the time of Adam Smith (and before) to see that.

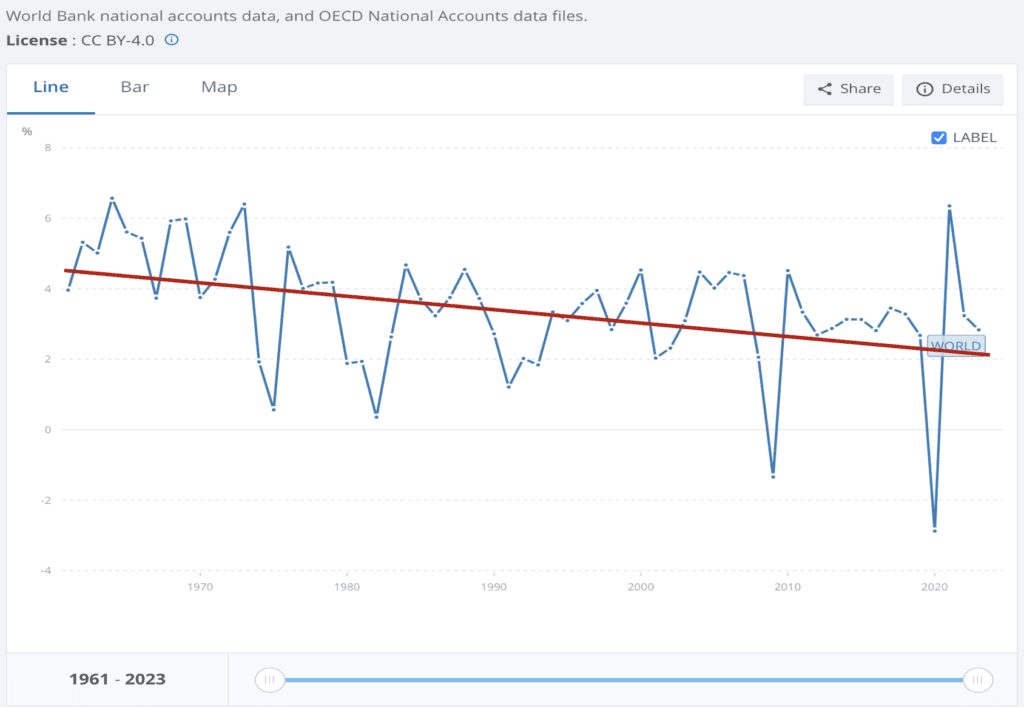

But that growth is not there anymore. Global GDP growth over the last few decades is decelerating.

The IMF warns that we’re heading for a “Tepid 20’s” – a decade of disappointing, sluggish growth unless we make serious course corrections.

At the same time, sales teams increasingly struggle to communicate value to customers, and customers are more selective and harder to convert.

“…we are indeed heading for the Tepid 20’s — a sluggish and disappointing decade“

International Monetary Fund

“Only 6% of executives are happy with their innovation initiatives”

McKinsey

Innovation teams pump out ideas but fail to move the growth needle—what’s been called “innovation theatre.”

McKinsey’s research is telling: Only 6% of executives are satisfied with their innovation initiatives. That means 94% are not. And many of them admit they don’t know what’s going wrong – or how to fix it.

Are we just performing innovation theater?

When there is a mismatch in understanding value between manufacturers and customers the sales and innovation processes are set up to eventually fail.

The same disconnect plays out in start-up failure rates. A top reason start-ups fail is lack of market fit. Customers simply don’t see the same value the founders see.

If we don’t have a clear, practical grasp of what value really is, or how it is created/emerges, our sales and innovation efforts will keep missing the mark.

What’s the answer? A focus on progress

At first glance, the answer seems simple: we just need a definition of value everyone can agree on.

But as we’ve seen, defining value isn’t simple at all. It’s notoriously slippery, contested, and hard to measure in practice.

So let’s try a different path. I propose we stop making value the primary focus of our efforts. That may sound radical, until we realise this only feels radical when we’re stuck in our traditional mindset, where value is synonymous with price.

Instead, I suggest we make progress our primary focus.

progress: moving, over time, to a more desirable state

And by progress, I’m referring to things like learning a language, travelling somewhere, putting up a picture frame, getting fit, etc etc.

Rather than chasing value as a transaction, we need to focus on enabling progress. Progress is tangible. It’s measurable. It’s what customers are actually seeking. And we can make it actionable:

- sales is the act of aligning offers to help make progress with the progress a customer is trying to make

- innovation is the act of finding ways to make better progress

- (sales may lead to in-line innovation)

And a focus on well-being

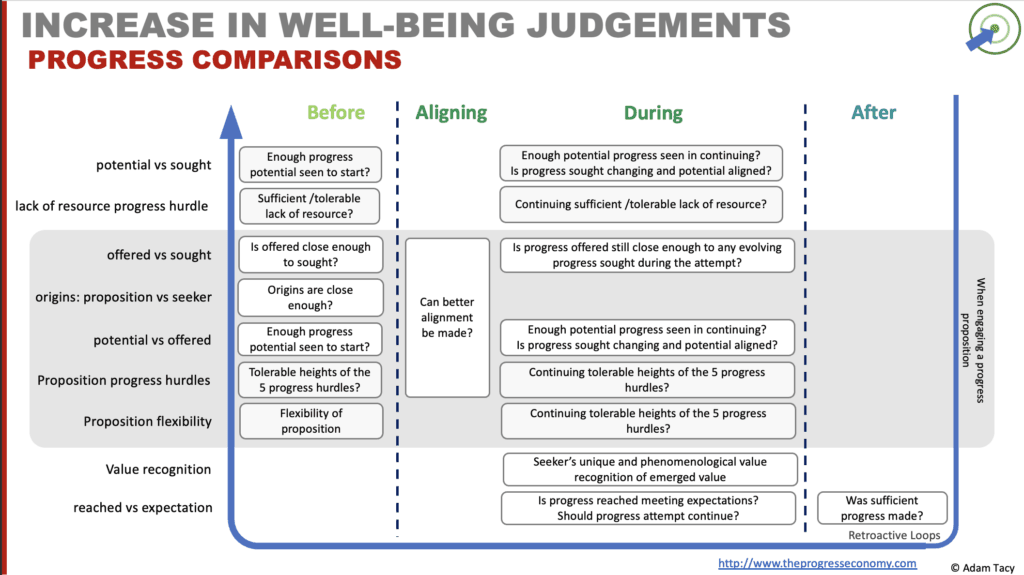

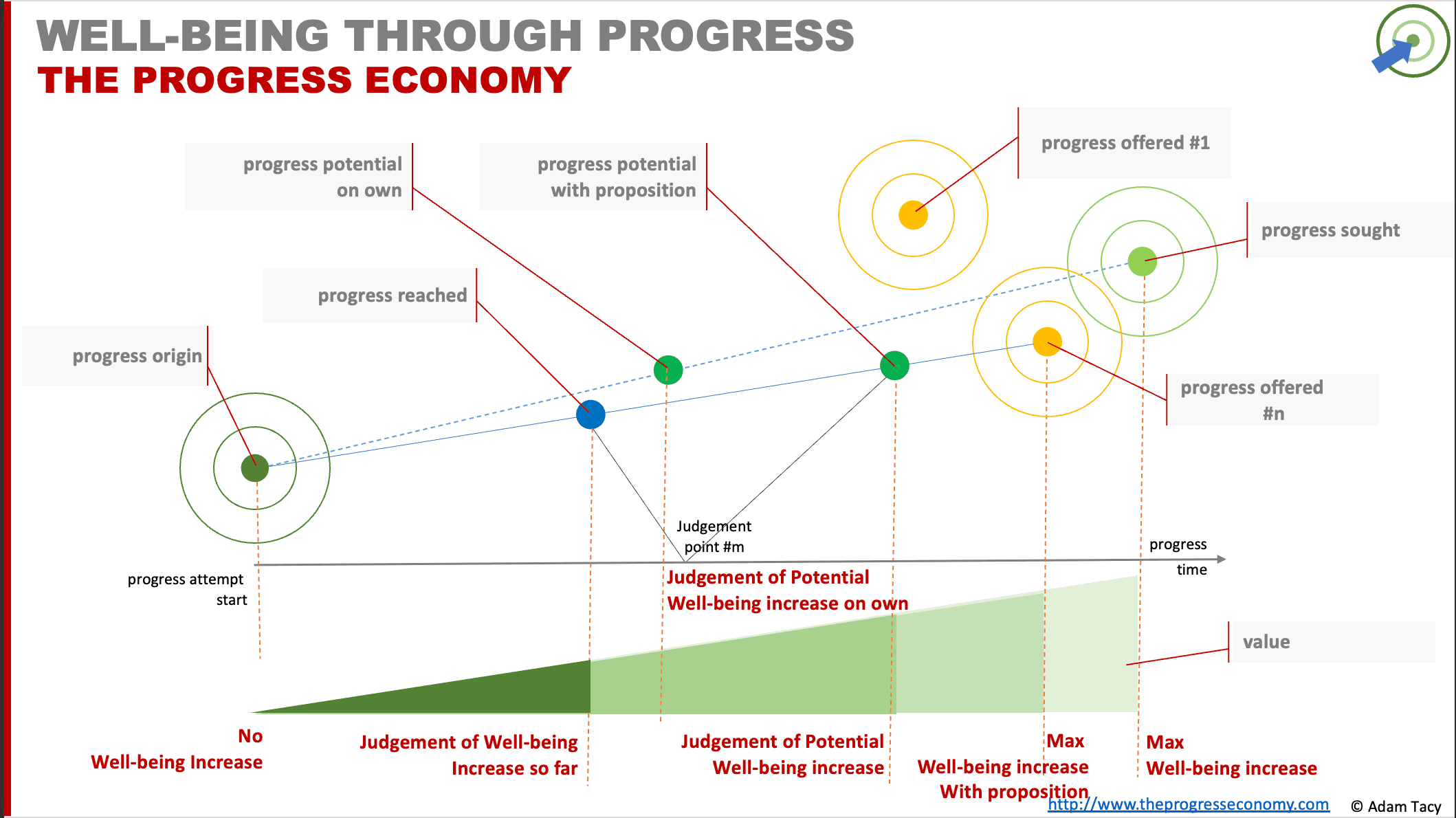

We need to introduce one more aspect to our thinking: well-being. Progress on its own gives us an operational model; but what does progress change beyond states? Making progress increases a Seeker’s well-being. And we measure well-being through various progress comparisons.

For example, potential increase in well-being is a comparison of progress sought (the state I want to get to) with progress potential (how far I think I can reach). Whereas emerged increase in well-being is a comparison of progress reached vs progress potential.

The well-being of the Progress Helper is also increased at the same time. This is because we exchange service. If a helper provides a service to a Seeker, then the Seeker provides a service back (although, this is very likely to be indirect). It’s a topic I discuss in more detail here. For now, you can think of this as how price is introduced back into our thinking (though price is more subtle than you are used to).

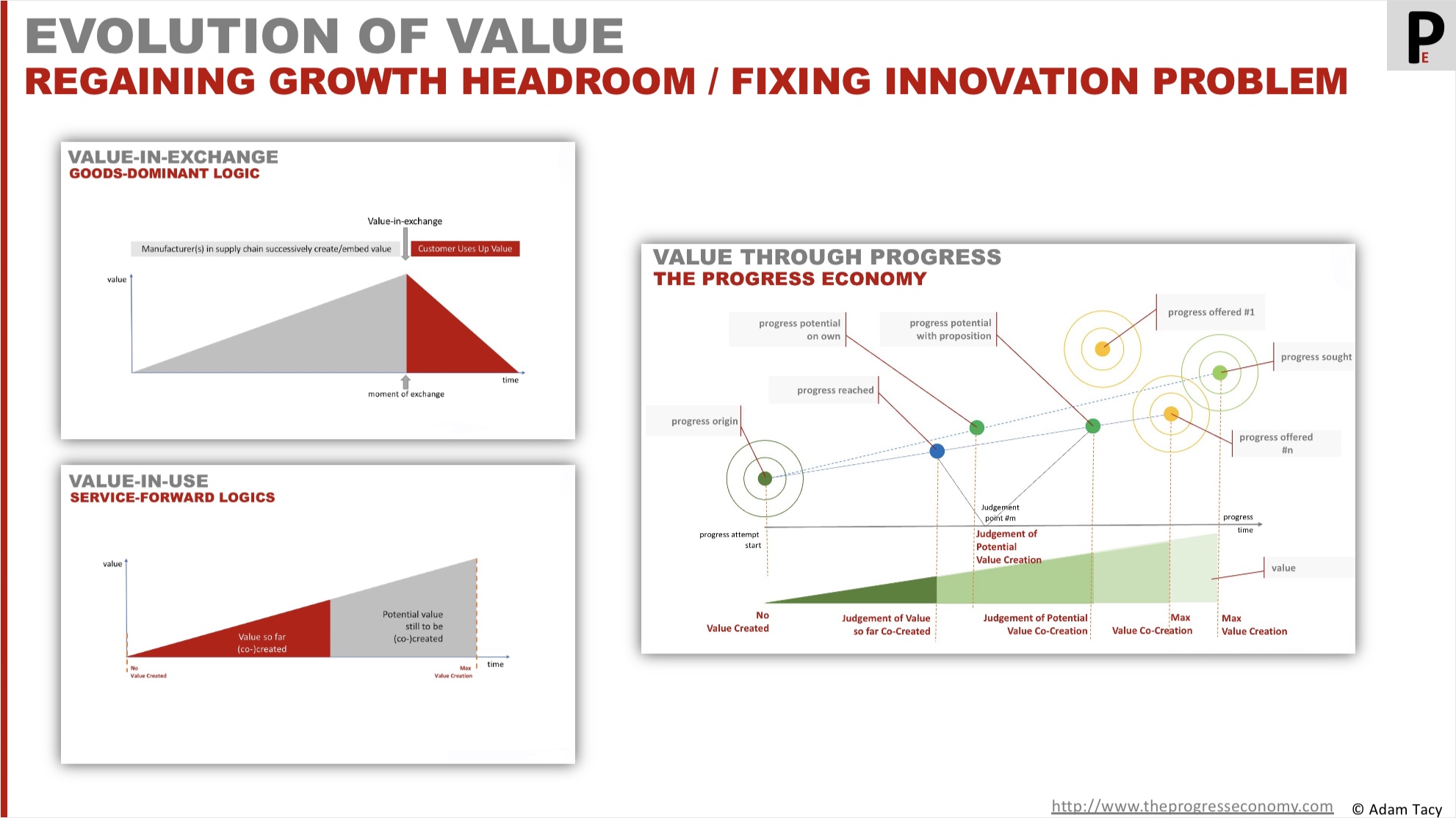

Getting to this answer is a process of moving from our traditional value-in-exchange model, to a value-in-use one, and then onwards to value-through-progress model.

Join me as we lightly explore these views on value models in this page whilst linking to separate deeper pages on each view. At the end of this page, we’ll compare and contrast each view in a table highlighting key attributes.

From our traditional view: Overview of value-in-exchange

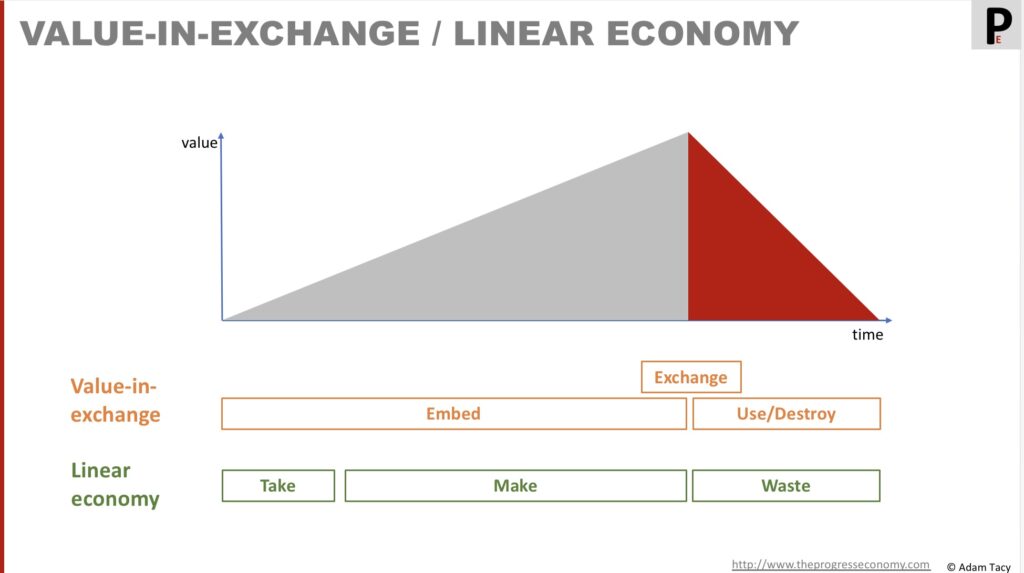

As we’ve discussed, our default understanding of value equates it to the maximum amount of money someone is willing to pay for a good or service. This is often referred to as value-in-exchange.

value-in-exchange – our traditional, manufacturing (goods-dominant), view. Where value is incrementally added through supply chain and we boil ir down to being the simple idea of how much someone is willing to pay

Value is incrementally added through the supply chain and ultimately distilled down to what someone is willing to pay at a point of exchange; and then subsequently destroyed or used up.

It is deeply rooted in manufacturing and reflects what is known as goods-dominant logic. We try and see services (plural) through the same lens, leading to a divisive, unhelpful, goods vs services perspective. This has been its strength over the centuries, when we were in a goods-dominant world.

Unfortunately, we’re not in a goods-dominant economy anymore (see “shift to service economy“). It also aligns with a linear economy way of thinking, hampering circular economy thinking. Ultimately, the focus on value exchange gives several blindspots:

- consistency over customisation

- chase next exchange over understanding/helping after exchange

- more exchanges are better than circular economy thinking or longevity

- goods better than services

- marketing myopia

- simple exchange over business model innovation

- value is determined by provider

Can we address those blind spots? I believe we can, by evolving to a different view of value.

Evolving to value in use

Grönroos observed:

It is of course only logical to assume that the value really emerges for customers when goods and services do something for them. Before this happens, only potential value exists.

Grönroos (2004) “Adopting a service logic for marketing”

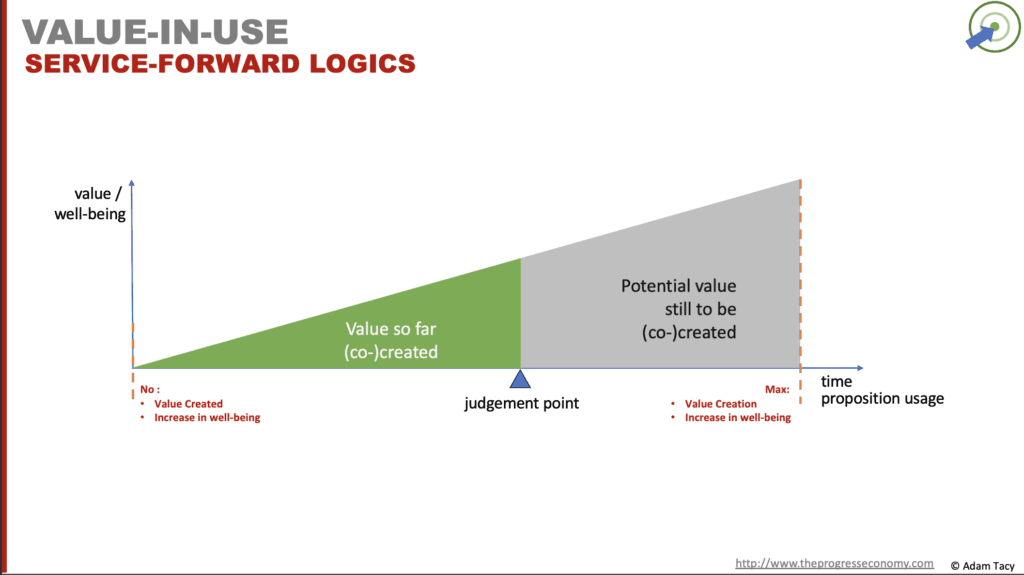

This is the value-in-use view:

value-in-use – A view of value creation that sees value being co-created through service (offered as value propositions) to improve a beneficiary’s well-being.

Since the point of exchange is removed, this view offers us the opportunity to minimise the value-in-exchange blindspots. We see everything as a service (singular) – applying competences (skills and knowledge) to help another – with goods assuming a role as distribution mechanism for service (no goods vs services debate here!). Now we can truly meet Levitt’s call to action:

“people don’t want to buy a 1/4 inch drill; they want a 1/4 inch hole”

Levitt (1975) “Marketing Myopia“

But there are some challenges with this perspective:

- well-being, whilst better than value, is still hard to define/agree upon

- requires deeper understanding of what beneficiary is trying to achieve

- we lose the connection to price / signalling value

- is still not the full picture – we miss descriptive levers to make sales/innovation more systematic

Observing that Well-being increases from making progress

With one more evolution we can solve even the challenges that value-in-use leaves.

We introduce the concept of progress – moving over time to a more desirable state – that acts as our actionable aspect; and well-being that is increased when progress is made.

Well-bieng-through-progress focusses on a Seeker’s desire to move to a more desirable state; and by doing so they increase their well-being. There is no increase in well-being before the progress journey begins, only potential, and maximum increase in well-being has emerged when the Seeker reaches their progress sought.

value-through-progress – well-being is increased as progress is made

Since this model builds on value-in-use we inherit the benefits. Progress gives us a framework to understand what a Seeker is trying to do. It is an actionable concept – Seekers look to make progress; propositions offer to help; sales looks to align propositions to a Seekers; innovation is all about improving progress that can be made.

Well-being emerges from a set of progress comparisons.

Progress between two states is more understandable, and actionable, than a focus on value. It reveals a number of tools and levers we can use to improve sales and innovation success. These include understanding:

- progress sought from a functional, non-functional and contextual perspective

- where progress seeker will begin their journey in terms of functional, non-functional, and, contextual elements

- a seeker’s foundational progress hurdle: a lack of resource (time, skills, knowledge, tools, etc)

- what supplementary resources (progress proposition) may help the seeker progress (includes the proposed progress-making activities and a resource mix)

- the five additional progress hurdles that proposition introduce, and how to minimise them (adoptability, resistance, lack of confidence, continuum mismatch, and inequitable exchange).

- which progress judgements a seeker makes (and how to influence them)

- that emerged increases in well-being, from making progress, needs to be recognised by a Seeker for it to be meaningful to them (akin to revenue recognition in firms)

Comparing the three Views

So how do these models compare? We can take various attributes, such as how value is defined, measured, created and destroyed, and which actor and resource focus, as well as how they impact innovation and the challenges the model had:

| value | value-in-exchange | value-in-use | well-being-through-progress |

|---|---|---|---|

| defined as… | …most a customer will pay | …increase in service system (including beneficiary) well-being | * …potential to reach seeker’s progress sought from their current progress origin * …how close seeker gets to their progress sought from their current progress origin (note that progress states comprise: functional, non-functional, and contextual elements) |

| measured through | * price | * increase in (service system) well-being | increase in well-being – a set of progress comparisons to expectations that vary per phase (before, during, and after), for example: * progress potential vs progress offered * progress reached vs progress offered * progress offered vs progress sought as well as heights of six progress hurdles |

| determined by | * firm * (can argue subsequently by market judgement of price asked) | * beneficiary | * increase in well-being is determined by the progress seeker * in some cases the progress helper may make their own progress comparisons (ie when creating/updating a proposition; or with a specific seeker when determining if making resources available will lead to a successful service exchange (direct or indirect)) |

| created by | * firm through embedding it in products | * co-created by all actors including the beneficiary during the use of value proposition | * emerges as seeker makes progress – on their own or with a progress proposition – progress-making activities may be driven by seeker, helper, or a combination * emerged increases in well-being need to be recognised by progress seeker – a process akin to revenue recognition – in order to be meaningful to them |

| destroyed by | * end customer after exchange made | * Potentially by actors in-use * often represented as co-destruction to align with co-creation position (although this is a misrepresentation) | * one or more involved actor hindering progress being made |

| resource focus | * operand (those that need acting upon for value to be created, typically goods) | * operant (those that act upon other resources resulting in value creation) * (goods are seen as mechanisms that freeze service for temporal/location distribution) | * operant * (goods distribute service) |

| actor focus | * firm | * beneficiary * a proposition sits on a continuum between enabling/relieving propositions | * progress seeker drives seeking progress * seeker drives progress attempt through progress-making activities unless they lack resource * helper provides supplementary resources including proposed progress-making activities * a proposition sits on a continuum between enabling/relieving propositions, located based on who (seeker or helper) performs majority of progress-making activities |

| innovation aims to… | * get higher price in exchange by embedding more value * or get more exchanges through lowering price | * improve well-being (beneficiary and/or service system) | * improve progress through some combination of: – improving how to make today’s progress – improving progress potential closer to individual seeker’s progress sought – reducing one or more of 6 progress hurdles – improving well-being recognition without impacting survivability of progress helper(s) |

| challenges | * has a number of blindspots * provides no obvious framework for innovation | * provides no obvious framework for innovation * price becomes undefined | * value doesn’t exist – we have a more complex increase in well-being view * (however that complexity provides a framework for innovation) |

| benefits | * has been wildly successfull | * offers to address the blindspots of value-in-exchange model | * inherits how value-in-use addresses value-in-exchange’s blindspots * adds the necessary operational aspect of progress |

Why this matters?

The Progress Economy reframes value as “value‑through‑progress” offering an actionable framework (of progress) as opposed to a hard to define concept (value). This shift transforms value from a transactional artifact into an ongoing signal of relevance, effectiveness, and customer alignment.

Let’s progress together through discussion…