Welcome to the operating model you should be building your organisation around.

We’re all seeking to make progress – to more desired states – with everything in life. Understanding what, why and how reveals a powerful operating system we can leverage to drive sales, fix innovation, and unlock growth,

What we’re thinking

Progress, as an operating model, reveals both how the world works, and the strategic moves and setup CxOs can make to improve sales, drive more systematic – and successful – innovation, and unlock growth.

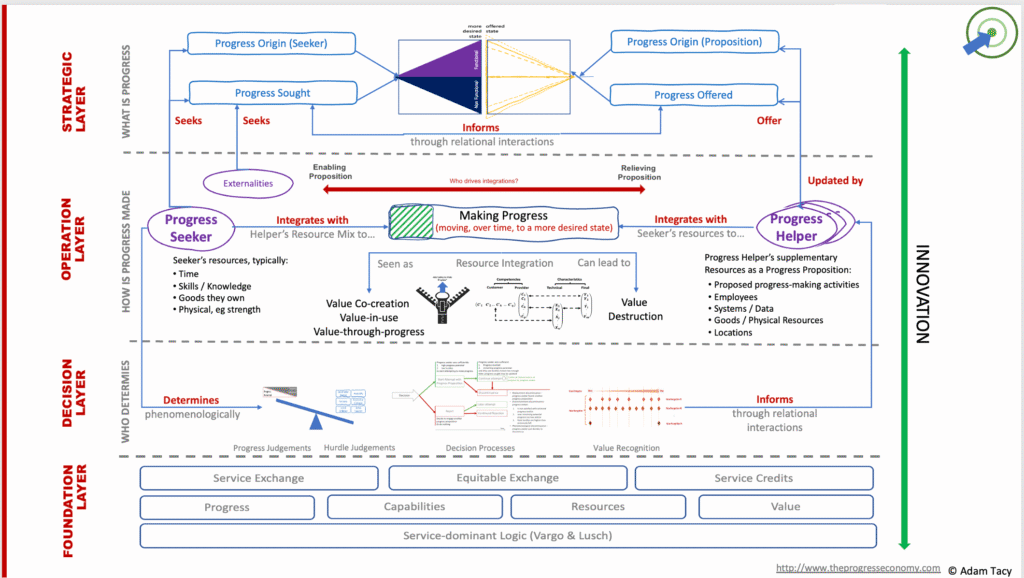

Our progress-based operating model naturally divides into four layers:

| layer | covers… |

|---|---|

| Strategic | what progress is being attempted – progress origins, progress sought, progress offered? Defining a new, actionable, definition of innovation; and the progress levers that help make it more systematic and successful. |

| Operational | how is progress made,; who is involved in making it? Who offers to help make progress and what are their propositions? Where and how are service credits involved? |

| Decision | what are progress potential and progress reached? What are the 6 progress hurdles? What is the Seeker’s decision process? How do Seekers use progress to judge value? What is value recognition and equitable service exchange? |

| Foundational | the shoulders the progress economy builds upon: progress, value, capabilities, resources, service exchange; service-dominant logic |

Within and across these layers we find a set of powerful insights, tools and progress levers that help us improve sales, fuel innovation, and accelerate growth.

Why this matters

It exposes several strategic insights:

- progress journeys constantly evolve » Seekers gain capabilities and grow expectations from all the progress attempts they are making (both in your and outside you industry/market); this is the dynamics behind Drucker’s “innovate or die“

- you need to deeply understand your Seekers progress journey » create propositions that resonate with them (closest to progress sought, lowest progress hurdles, and quickest value recognition)

- dialogue and interaction with progress seekers (customers, guests, etc) is key – though may be less important on simpler progress journeys

- sales is about aligning progress help to progress journey – during which local innovation may occur – not pitching features

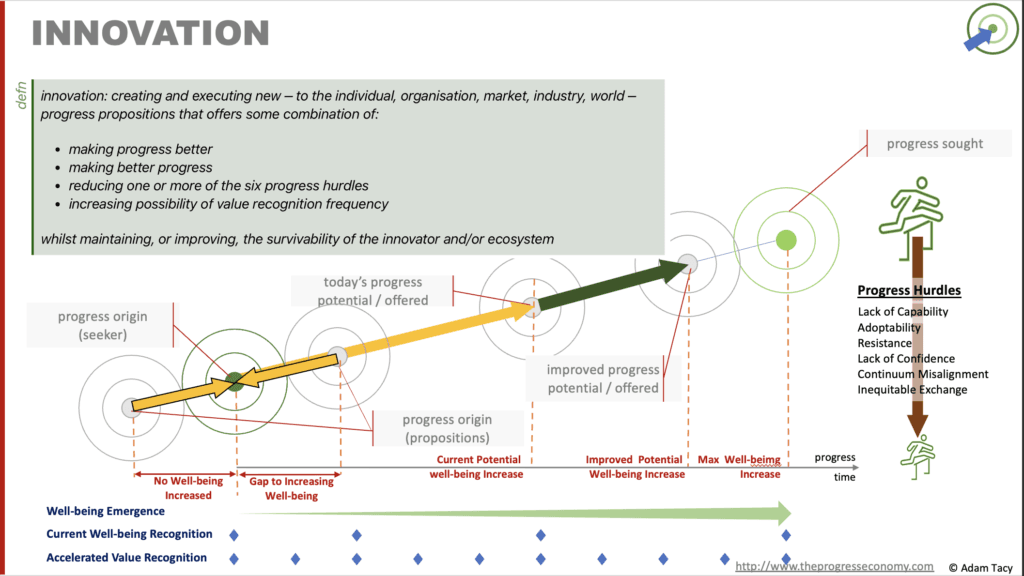

- innovation is about making today’s progress better; making better progress than possible today; reducing one or more of the 6 defined progress hurdles; and/or accelerating possibility for value recognition

- segmentation on progress is superior to segmentation on features or demographics

Progress as an operating model

Progress – our deceptively simple concept – blossoms into a powerful four-layer operating model explaining how the world truly works. When we understand these workings, we can put progress at the centre of strategic approaches; unlocking insights for improving sales, fuelling innovation, and accelerating growth.

Progress, is a strategically insightful four layered – strategic, operational, decision, and, foundation – operating model

We start our model with a few essentials:

- the definition of progress » moving over time to a more desirable state (functional, non-functional and contextual)

- we are all progress seekers, in all aspects of our lives

- we struggle to progress as we often lack capabilities

- others have the capabilities we need to make our progress

It is this imbalance of capability distribution that drives service exchange, which is the true basic unit of economic activity

From here we can start asking what does progress really mean? How is progress made, what does making progress mean, what prevents us making progress? What decisions are made in the act of making progress? Who is involved in making progress? And more.

The answers to those questions lead us to the progress economy – a four layer operating model of life! And leveraging that is how to improve sales, fix innovation, and drive growth.

Introducing the four layers

Here, then, are the four layers of our operating model – the foundation, decision, operational, and strategic layers:

Which we can briefly described as follows:

| Layer | description |

|---|---|

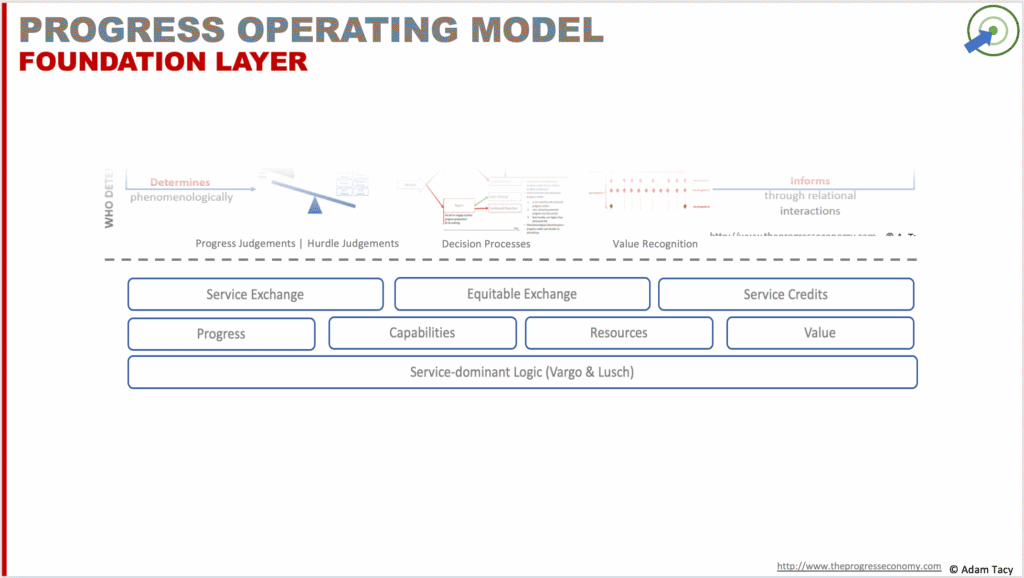

| foundation | we build on, and out from, Vargo & Lusch’s service-dominant logic – an evolution to the traditional goods-dominant logic (which, whilst previously successful, has blindspots now holding us back) – and subsequent new definitions of key concepts, like progress, capabilities, resources, and how we re-understand value |

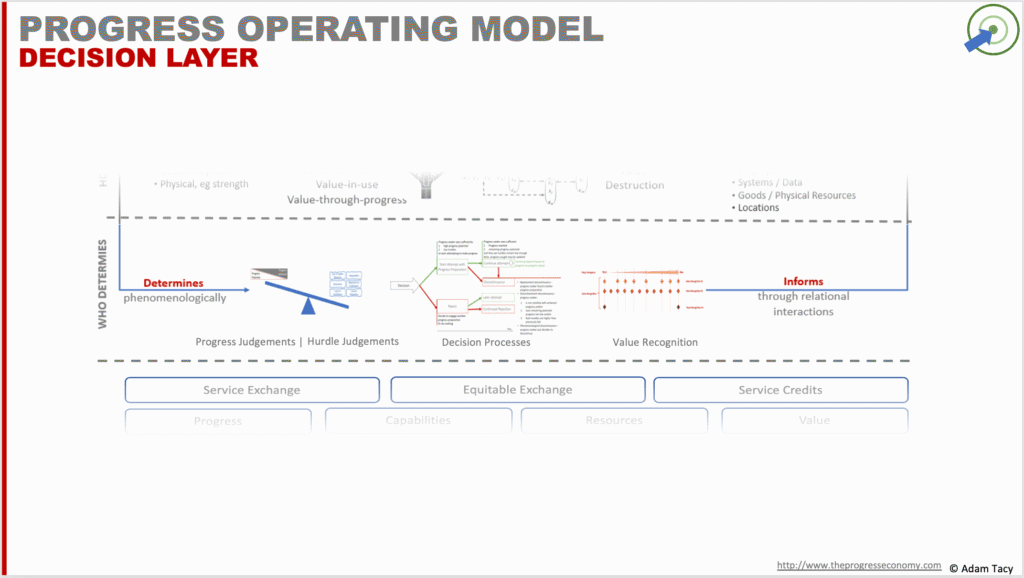

| decision | describes the decisions that actors, predominantly the Seeker, make during progress journeys – including a definable progress decision process that Seeker’s follow (consciously or unconsciously), the six hurdles that hinder progress, how value is actually a series of progress comparisons, and that a Seeker needs to recognise emerged value for it to be meaningful to them; these decisions are all phenomenological |

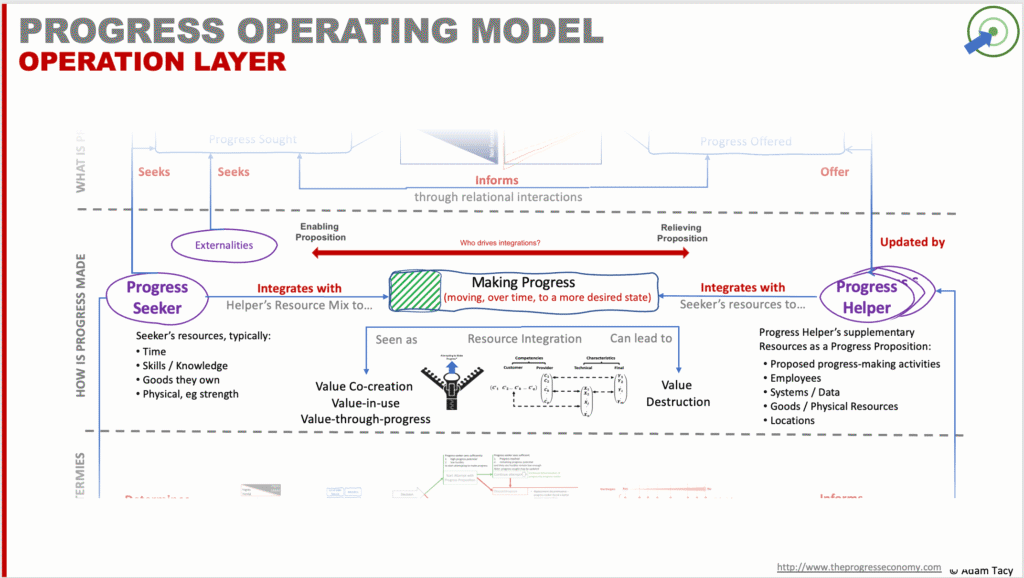

| operational | how progress is made – progress journey’s become progress attempts undertaken through progress-making activities (resource integration, applying capabilities); where Seeker’s lack capability they may engage a progress proposition (supplementary capabilities carried by a specific resource mix) |

| strategic | the strategic interface between a Seeker’s progress journey between progress origin and progress sought, and a Helper’s offer to help reach a state of progress offered from an assumed origin; it’s marketing, sales, and innovation |

When we bring these layers together, we find the actionable operating model for how life actually works – and, with it, a clearer view of what we can strategically influence to make progress easier and outcomes better.

Within and across the layers lie a set of powerful insights, tools and progress levers. Each offering practical ways for Helpers (you) to improve the progress that Seekers look to make, reduce their hurdles, and enhance the perceived value of what you offer.

Underlying Shifts in the progress economy

To fully grasp this new operating model, there are five shifts in your thinking needed.

1. Value is secondary to progress. Value is no longer the focus of our efforts. It emerges from sets of progress comparisons; therefore progress must be our key focus.

Potential value, for instance, is a Seeker’s comparison of how much progress they feel they can make towards their progress sought. Whereas emerged value is how much progress they feel they have made towards their progress sought – where maximum value emerges when a Seeker reaches their progress sought.

Emerged value needs to be recognised by a Seeker for it to be meaningful – a process akin to revenue recognition in accounting

2. Value model shifts. Since we see value as emerging from progress, our value model of value-in-exchange – where we exchange cash for products with embedded value – is no longer helpful. We shift to a value-through-progress model – where the process of making progress co-creates value.

3. Service – from output to outcome. We use service (singular) – the “application of capabilities to benefit oneself or others” – in the progress economy; that is fundamentally different to services (plural), which is our traditional view, and is an output, comparable to goods.

4. Goods are distributors of service. We use goods to freeze and distribute service (singular). The service can then be unfrozen ithrough resource integration when and where needed. We have no unhelpful goods vs services debate. A bottle of water and water from a tap/faucet are the same thing, yet traditional we would think of one as a goods the other a services.

5. Price signals effort. We move on from price signalling value; now it signals the effort a progress helper expects to get in service you provide to them for the effort they put in service to you. This can be in direct service, or more often that is masked by service credits, which mediate temporal and magnitude differences and lubricate indirect service; cash has been a successful implementation of service credits.

There’s a lot to cover, so I’ve split this article into four pages, one for each layer, and tried to pull out the key points in boxes like the following for those looking to skim through.

There’s no getting away from this being a long (and rich on strategic insights) article…I’ll highlight the key insights in boxes like this for those wishing to skim through.

With this background in mind, let’s start exploring the strategic layer. It’s the where we get to explore the progress being sought and offered.

Strategic layer: setting the direction

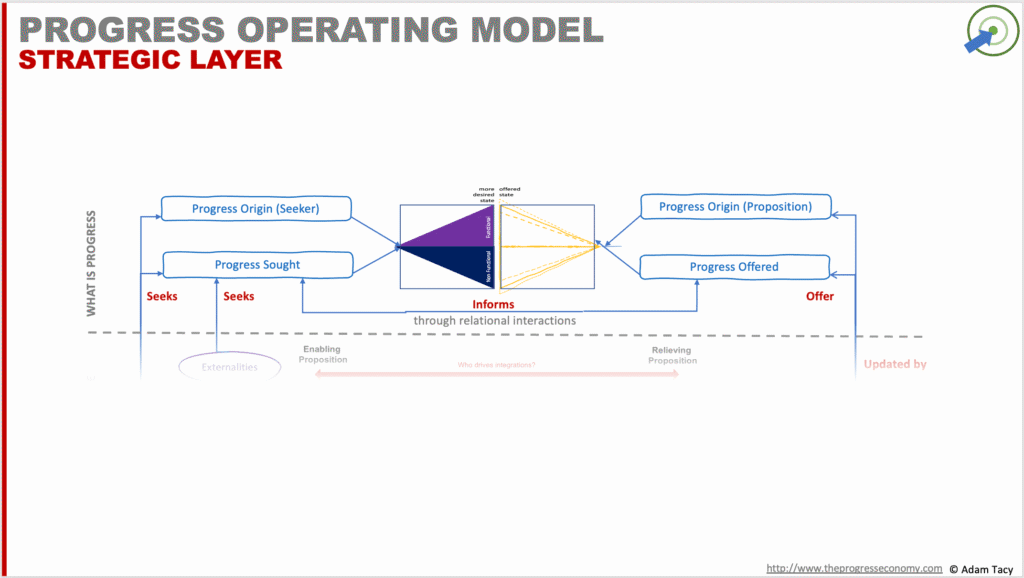

At the strategic layer of the Progress Economy, we find the fundamental waypoints of progress – progress sought, progress offered and two progress origins – and why they matter for sales, innovation, and, daily execution.

Strategic layer: where a proposition’s progress offered and origin meets a Seeker’s progress sought and origin – a fertile ground for innovation and sales

Wired together, these waypoints look like this:

It’s a layer where we’ll uncover five strategic insights Helpers should keep in mind:

- deeply understand Seekers’ progress origin and progress sought – across all three dimensions: functional, non-functional, and contextual.

- identify the Seeker’s missing capabilities – and understand the specific context in which they’re needed.

- identify if there are contexts Seekers may wish to change – turn those into functional/non-functional aspects of new propositions

- customisation should be the normative goal

- segment by progress (sought and origin), not by demographics or product features – group Seekers by similarity in progress journeys to reduce unnecessary customisation.

- design propositions that

- maximise coverage of a Seeker’s journey (either by itself, or filling in gaps)

- minimise the six progress hurdles

- offer the resource mix a Seeker is looking for – pay attention to the position of Seeker on the proposition continuum

As the name suggests, everything in the Progress Economy begins with understanding what progress is.

Seeking Progress

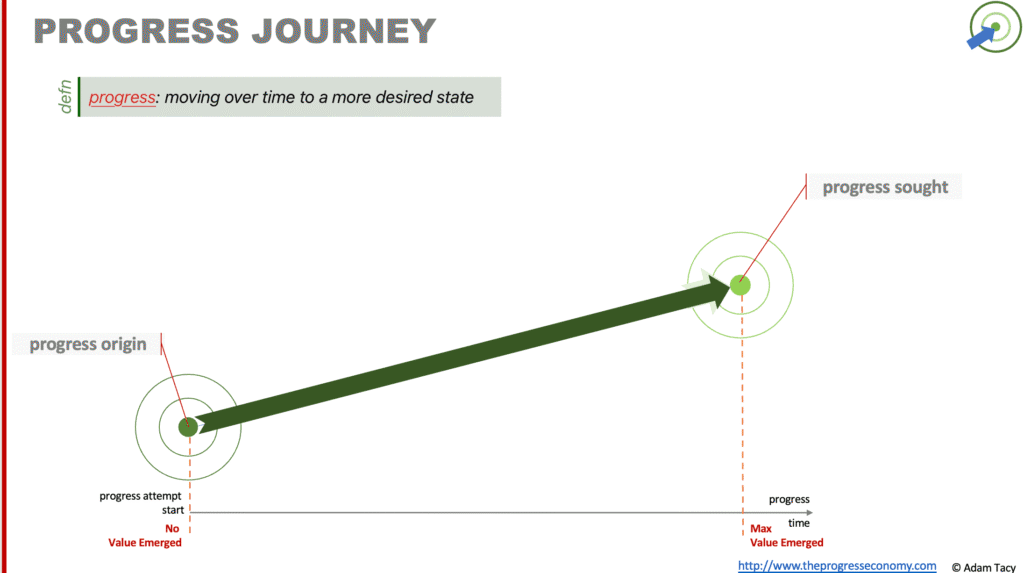

We begin with a simple, powerful premise: everyone is trying to move from their progress origin (where they are right now) to their more desired future state (their progress sought).

progress: moving, over time, towards a more desired state

These individuals and organisations are Progress Seekers (or simply, Seekers). Their movement is a progress journey – the key mental picture in the Progress Economy. In fact, we’ll often visualise these journeys using a progress diagram, the simplest of which is below.

It’s worth noting that whilst a Seeker’s progress journey spans all aspects of their life, we often focus on one aspect at a time for practical analysis. Though we’ll still refer to an aspect as a progress journey.

Seekers want to get from their individual progress origin to their individual more desired state of progress sought – it is a progress journey (which we can visualise on a progress diagram)

Each progress journey is a change across the three, equally important, dimensions of progress state. Although these changes differ in range as follows:

| progress dimension | change description |

|---|---|

| functional | typically changes between origin and sought |

| non-functional | may or may not change |

| contextual | we’ll decide that, by convention, contextual progress never changes in a progress journey |

Let’s unpack each of these.

The three dimensions of progress

The functional progress sought is often the easiest to identify. It’s the completed a half marathon, arrived in Oslo, learnt Mandarin Chinese, increased wealth, enjoyed myself, defended against missile attack, recovered from an illness, etc. The functional progress origin may be quite varied, and is equally important to know. The marathon journey, for example, starts at different places for a non-runner, a first timer, and a seasoned competitor. The functional journey is the verb: training, travelling, learning etc.

Non-functional progress accompanies functional progress. This includes how one wishes to experience the journey – quickly, safely, easily, enjoyably, flexibly. Sometimes this will change over the journey. A seeker may wish to gain autonomy, or the emotional reward of a sense of achievement. Othertimes it will stay the same. There are few journeys where a Seeker wants to start with low levels of safety, looking to increase that by the end (few, but not none).

And contextual progress captures the environment in which progress is attempted. Conditions like “in rush hour” or “no driving license” fundamentally alter the nature of a progress attempt. As Christensen rightly observed:

A job can only be defined – and a successful solution created – relative to the specific context in which it arises

Christensen, C (2016) “Competing against luck”

For clarity of analysis, we make the convention that context doesn’t change during a journey. If the context needs to change, we consider it as a separate progress journey aspect with a change in functional or non-functional dimensions. “No driver’s license” context, for example, is changed by a progress journey with a functional progress sought of “obtained driving license” (and a progress origin reflecting the Seeker’s situation – never driven, or have driven but not on roads, etc).

All three dimensions of progress – functional, non-functional and contextual – are equally important.

Misunderstanding, or not knowing, one or more dimensions of your Seeker’s progress origin or progress sought, risks making your sales and innovation approaches irrelevant.

In combination, the progress origin, progress sought, and the journey between them provide a deep understanding of what Christensen and Ulwick separately refer to as a job-to-be-done. (We’ll find the progress economy explains many of today’s leading, and yesterday’s foundational, innovation theories).

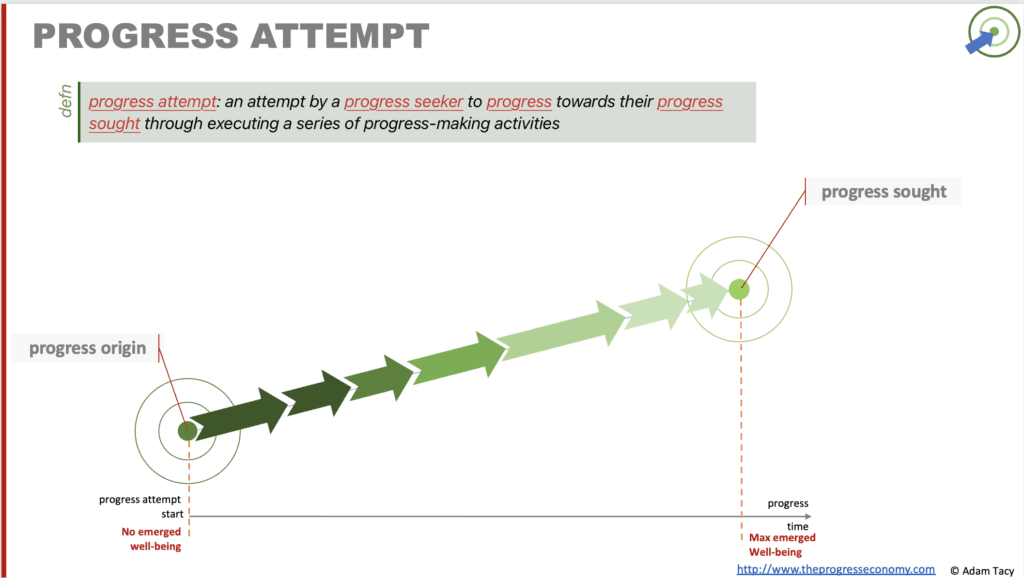

Attempting progress

While a topic for the operational layer, we need to briefly examine how a Seeker makes a progress attempt to properly frame the concept of progress offered – the state a proposition offers to help reach.

Seekers apply capabilities they have access to – skills, knowledge, physical (eg strength), natural (eg power in wind), abstract (eg availability carried by time) aspects, and more – to make progress. These capabilities are carried by resources which they integrate in progress-making activities, attempting to make progress.

In the complete absence of Progress Helpers, the capabilities we would have are learnings we’ve made ourselves, skills we’ve developed in isolation etc, and capabilities carried by natural items in our environment we’ve worked out how to harness (the leverage capability of a fallen branch, for example). It’s a limited world. Realistically, we also have access to capabilities/resources from previous progress attempts involving helpers, such as education, provided tools, and of course learnings from parents and society.

Still, our progress sought is ever evolving, and is more complex than just survival. So, despite what we can draw on, Seekers may still face a lack of some or all of the capabilities needed to make a progress attempt. We have a lack of capability progress hurdle.

Seekers attempt progress by integrating resources that carry capability (skills, knowledge, physical (eg strength), natural (eg power in wind), abstract (eg availability carried by time), etc).

Lacking capability is both the foundational progress hurdle and is the opportunity for progress helpers to offer propositions (bundles of supplementary capabilities, carried by a specific resource mix).

This is where Progress Helpers enter. They offer progress propositions – bundles of supplementary capabilities (carried by a specific resources mix) – to help Seekers in reaching a state of progress offered. That needs to be close enough to a Seeker’s progress sought for it to be attractive.

Helpers gain these capabilities in a number of ways. Perhaps they persevered with an attempt and developed them; or they identified a gap and worked hard to reduce (eg R&D); or they may have observed something in another market/industry and transferred it; or they took training from another helper; or they have other skills that they use to help a Seeker identify how to progress.

Progress Offered / Sought: The obvious strategic fit

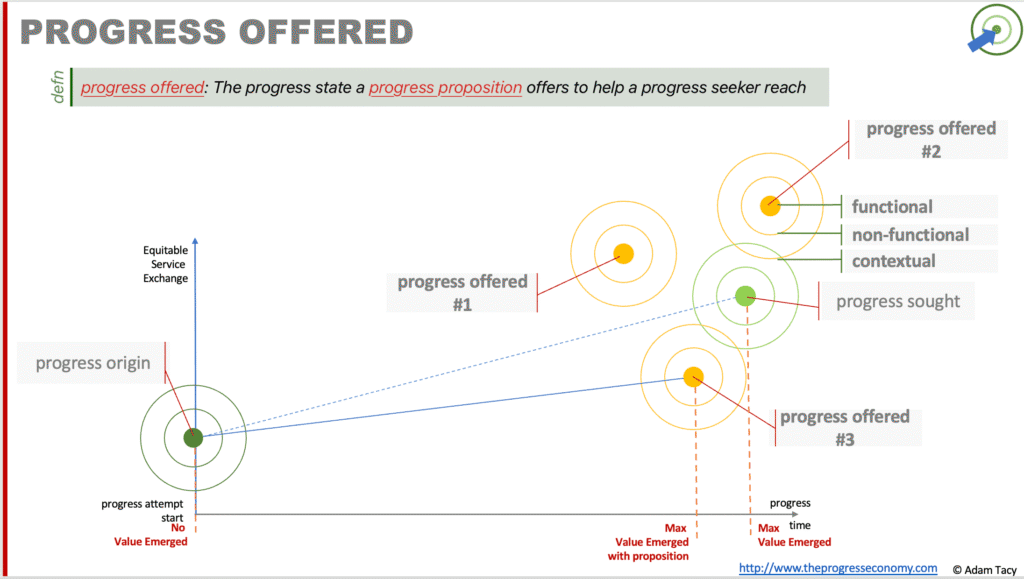

A Helper’s proposition offers to support a Seeker in reaching a specific progress state: the progress offered.

Ideally, this matches the Seeker’s progress sought. In practice, such immediate alignment is rare. Usually, the situation is that seen in the following progress diagram.

Most propositions approximate what the Seeker wants. There are inevitable misalignments across one or more of the three progress dimensions. Seekers look for the best-fit and decide whether the proposition is close enough. That is a phenomenological decision, based on lived experience, current situational context, and their assessment of six progress hurdles (all leading to the concept of potential value)

A helper should try to align their proposition’s progress offered with the Seeker’s progress sought – misalignment leads to lower value emergence for a Seeker

Misalignment can cut both ways.

- If progress offered falls short of progress sought, the Seeker may

- abandon, or not start, the attempt

- or look to see if they can chain multiple propositions together to reach their progress sought

- If progress offered exceeds the Seeker’s progress sought, the result may be:

- over-engineering leading to overpricing; raising the inequitable exchange hurdle and non-engagement

- the Seeker evolving their progress sought due to this new information

This second scenario creates fertile ground for disruptive innovation, as defined by Clayton Christensen in The Innovator’s Dilemma. In this dynamic, Seekers continuously evolve their progress sought, raising expectations over time. Incumbent Helpers respond by improving their progress offered to match these rising demands.

The progress economy explains Christensen’s disruptive innovation

But progress sought is not homogenous and this constant evolution comes at a cost: Seekers with more modest needs are left behind, now expected to exchange for more progress than they require—or can effectively use. This opens the door for a new entrant, typically leveraging a novel technology. Initially, their proposition falls short of mainstream expectations, but it’s “good enough” for underserved Seekers. Crucially, it’s also simpler, cheaper, or more accessible. The new entrant also chases it’s new Seekers’ evolving progress sought.

As both helpers improve their progress offered, the new entrant moves steadily towards the mainstream, while the incumbent pushes toward the high end. If the new entrant eventually satisfies the mainstream Seeker’s expectations, the incumbent is disrupted – not because they failed to innovate, but because they innovated upmarket and left room below.

Still, as I mention, over-offering on progress sought is not inherently negative. In some cases, it encourages the Seeker to stretch their ambitions in ways that are beneficial to them.

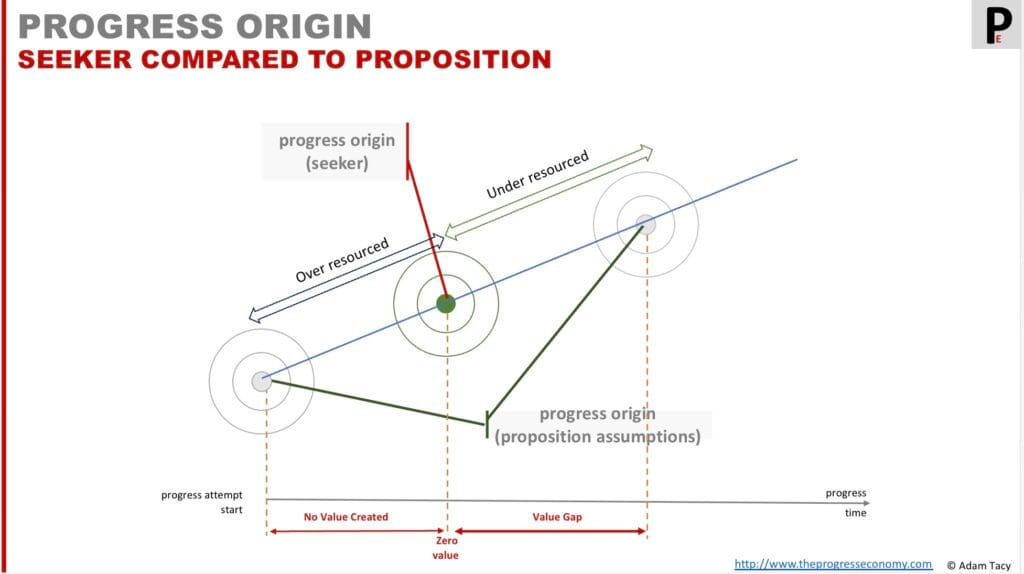

What’s often overlooked, but strategically critical, is the progress origin assumed by the Helper.

Progress Origins: Another important strategic fit decision

Just as Seekers have a progress origin, so do propositions. Helpers need to assume a starting point when they define their offer. If this origin is misjudged, say, overestimating what the Seeker is already capable of, then the Helper may under-deliver on required capabilities. The Seeker’s lack of capabilities hurdle may still be too high, and progress stalls.

Often forgotten, but a mistake to do so: a helper should try to align their proposition’s progress origin with the Seeker’s progress origin – misalignment may not reduce the lack of capabilities hurdle enough, or may lead to wasteful/frustrating offerings

Consider a public transport service whose nearest bus stop is 2km from the community it intends to serve. The proposition’s origin does not match the Seeker’s, and the gap likely leads to limited or no engagement.

Conversely, offering too many capabilities, especially if the proposed progress-making activities are mandatory, can backfire. Imagine forcing an intermediate Mandarin speaker through a 10-week beginner course before they can start learning. The Seeker may feel their progress is blocked because what’s offered is irrelevant to their current state. This may lead to value destruction. They’ll also likely feel a high inequitable exchange hurdle since you want exchange for something that is not useful to them.

When a proposition’s progress origin and progress offered align closely with the Seeker’s own origin and sought state, value emerges rapidly. Misalignment, however, leads to friction, increased effort, and potentially disengagement.

Strategically, you should identify and reduce any origins gap. What can a Helper do? One option is customisation.

Strategic Customisation

To reduce misalignment, Helpers can choose to offer customisation to either the progress origin, the progress offered, or both. This enables a proposition to better match a Seeker’s specific journey.

In theory, the ideal proposition would be fully customisable, adapting seamlessly to any Seeker’s origin and progress sought. In practice, customisation takes Helper effort, and that translates to an increased equitable exchange demand, potentially increasing the inequitable exchange hurdle. The ideal proposition gains the highest equitable exchange needs.

This trade-off is well understood in many markets. A Savile Row suit, for example, offers precision tailoring that justifies its higher price. Off-the-rack options, by contrast, minimise customisation to serve a broader audience at lower cost.

The strategic question for Helpers is this: How much customisation will our market support, and how much are you willing to offer?

Vargo & Lusch (service-dominant logic) tell us customisation should be the normative marketing goal.

A helper should therefore offer to customise their offering to align their proposition’s progress offered with a Seeker’s progress sought and their proposition’s progress origin to the Seeker’s.

However, customisation comes with an increased equitable exchange progress hurdle.

Yet there is also a strategic opportunity here too. Where there are markets that currently offer little customisation, is there an opportunity for you to offer more customisation, or for others to offer that customisation? . Some high-street suit retailers might offer an additional limited tailoring service; traditional tailors offer even more for those who seek further progress.

Another large example is after-market customisations for cars. There is a sizeable revenue that car manufacturers leave for others to grab.

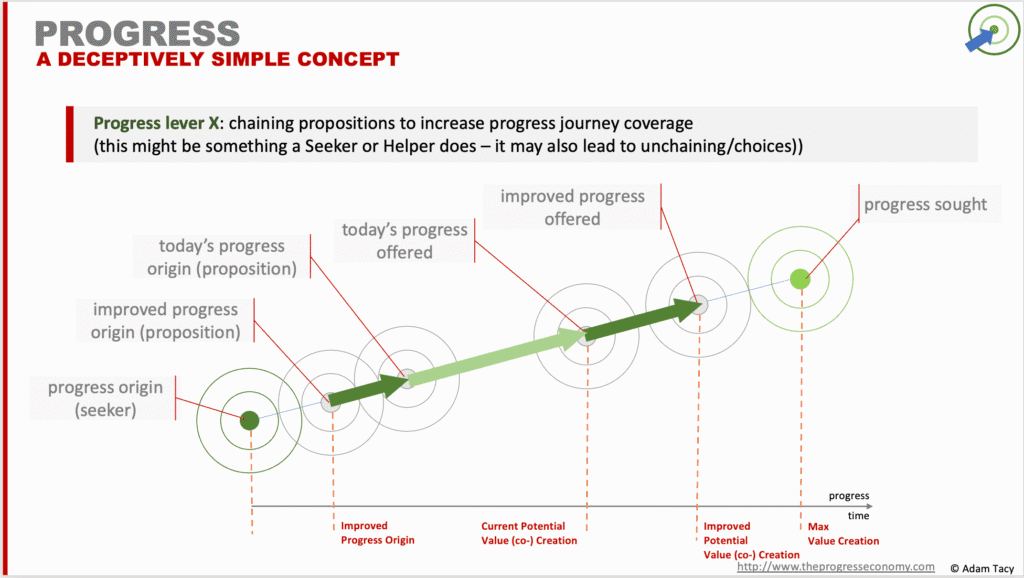

Can you offer customisation where the incumbent doesn’t? Or as an incumbent, is there part of the progress journey you don’t cover that you could?

Progress Seekers are adept at chaining propositions to cover more of their progress journey than one helper offers. Are you looking for these “completion” opportunities? Can you reduce a Seeker’s friction by chaining together propositions for them? A package holiday is more friction free for a Seeker than booking flights, transport and hotel separately.

Strategic unbundling

And this discussion on bundling propositions offers another insight. Can you unchain/unbundle your existing proposition to offer choices?

When I order online, I often see various options for payment (cards, direct bank transfer etc) as well as for delivery (often several courier companies, or send to storage boxes, or last mile deliverers).

Is there progress you currently offer that can be unbundled to offer the Seeker greater choice (that help them make better progress)?

Ultimately, the amount of customisation needed by a Seeker to make there progress with your proposition depends on the gaps between the origins and progress sought/offered. Segmentation can help reduce those gaps.

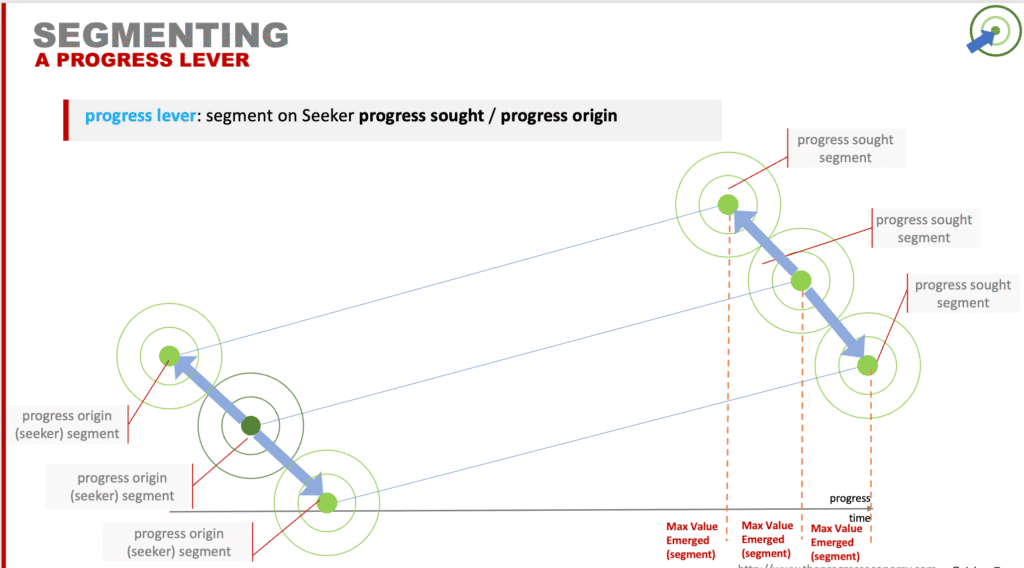

Strategic segmentation

We can reduce the amount of in-line customisation required by getting initially closer alignment of progress origin/sought.

An approach strategic Helpers employ to minimise customisation, where there is a large spread of origins/progress sought, is to segment Seeker’s by the three progress dimensions (not by the usual product features or demographics) and then designing more initially attractive propositions.

Take learning Mandarin Chinese. There is a market for personalised one-one teaching (the ultimate in customisation). However, that market size is small since it requires large equitable exchange (the Helper needs to put in a lot of effort and therefore expects higher exchange).

What we typically find are propositions segmented on starting and end level capabilities – say beginner, intermediate and advanced level courses – which are tied to a recognised curriculum. Being more generic brings down the equitable exchange. Each level can be chained, but there’s an expectation of having completed beginner level before starting the intermediate, etc. And being tied to a curriculum gives a recognised measure of progress.

The power of segmenting on progress comes when we think of context and non-functional. These help drive the above propositions into in-person class room, on-line class room, online recorded (or other recorded, for those of us still with CDs, or tape players…). Or “functional” segmentation – learn what you need for holiday or dedicated to specific careers like medicine or computing.

Can you strategically segmentation your Seekers on the three dimensions of progress for both progress origin and progress sought? It reduces in-line customisation of propositions (something that increases inequitable exchange progress hurdle) and increases attractiveness of your propositions?

(you could even argue “learning” is too restrictive here. Perhaps the Seeker wants “to communicate whilst on holiday” – learning Chinese is one solution, a translator app another, access to a translator is another, I’m sure there’s more. “Learning” is fine if the non-functional progress sought is, say, “sense of achievement” – this is why understanding all three dimensions is important)

Removing contextual constraints

You might remember earlier I said that we don’t, by convention, change the contextual progress during a progress attempt. That is mainly because we want to manage our analysis, but it also often makes sense in the real world.

Let’s say a Seeker’s functional progress sought is to travel to a place 100km away and some contextual progress that they don’t have a driving license. If they want to drive themselves in order to make their journey, it usually makes more sense for them to have an additional progress sought of “obtained driving license” rather than a combined one of “obtain driving license and then drive 100km”.

Seekers may look to, or need to, change their contextual progress to engage with your proposition – can you help?

You should strategically look for these opportunities.

Searching for unrecognised progress sought

I like Kim and Mauborgne’s Blue Ocean strategy – a strategy to apply cost and value innovation to identify markets where there are no competitors. It comes with several tools, that can be leveraged in the progress economy to find blue oceans.

Kim and Mauborgne’s Blue Ocean can be applied to a captured view of progress sought/offered to hunt for new seekers

We can, for example, leverage their strategy canvas and our three dimensions of progress on progress sought. Once mapped out, we can apply their four action framework to raise, reduce, eliminate or create new aspects of progress sought to find blue oceans.

Sales as a strategic alignment

Sales, viewed through the Progress Economy lens, is no longer about pitching features, it’s about aligning your proposition with the Seeker’s progress journey. It is persuading the Seeker that your proposition helps them make the best possible progress, from where they currently are, with the lowest hurdles acceptable to them.

Key alignment questions include, does the Seeker believe the proposition:

- gets them closer/closest to their progress sought?

- begins close enough to their progress origin to make engagement feel easy?

- lowers the six progress hurdles enough – such as lack of competence, adoptability, or inequitable exchange (simplified here as cost)?

On a progress diagram, it looks like this:

The more complex the progress you are offering to help with, the more you need to deeply understand your Seeker’s progress origin and progress sought. It’s a discovery process before they engage your proposition, and then a continuing journey together as the progress is made. Your aim is to minimise value destruction – which, unlike in the traditional value-in-exchange model of value, is defined as when one or both parties do something to hamper progress.

Sales is about showing a Seeker your proposition best aligns with their progress origin and progress sought (along the way, local innovation may occur – how do you capture and spread that?)

Crucially, front-line teams play a strategic role. They uncover local adaptations, workarounds, new use cases, and organic innovation. These aren’t anomalies, they’re signals. Smart organisations capture, interpret, and scale these insights across their sales process, operational model, and offerings.

Sales doesn’t end at the start of progress attempt. Continued dialogue during the progress journey ensures alignment, helps steer outcomes, and surfaces new needs and innovations. That said, the simpler the proposition (low progress hurdles and minimal progress-making activities), the less interaction may be required, and indeed may be possible.

Helping make progress suggests the sales process is one of dialogue across the progress attempt (to increase progress and minimise value destruction – lack of progress).

Though the simpler/shorter a proposition’s span of progress origin to progress offered is, the less important constant progress appears to be. However, initial and final discussion may still prove beneficial to both parties.

innovation: Making better progress

Peter Drucker famously wrote that a business has only two functions: marketing and innovation.

Because the purpose of business is to create a customer, the business enterprise has two–and only two–basic functions: marketing and innovation.

Peter Drucker

In the Progress Economy, these two imperatives take on new clarity. Marketing becomes the act of identifying the Seeker’s progress origin and progress sought, segmenting them based on their progress journeys, and interacting with them throughout their progress attempts.

How do you help a Seeker mke current progress better, make better progress, reduce one, or more, of the six progress hurdles, and/or increase value recognition frequency?

Innovation becomes the act of improving progress:

- improving progress that can be currently made

- improving progress towards progress sought from progress origin – filling in more of the progress journey

- reducing one or more of the six progress hurdles – more adoptable, lower equitable exchange etc

In short, marketing discovers and aligns; innovation enables and improves.

Innovation can be driven by Seekers themselves – for example:

- using propositions in alternative ways beyond their original intent

- combining available propositions to span more of their progress journey

- creatively reconfiguring their own progress-making activities using available capabilities

Mostly we’ll focus on Helpers, where innovation revolves around creating or improving a proposition (to better help a Seeker). That itself relates to:

- updating proposed progress-making activities

- introducing new capabilities

- improving or swapping resources (that carry capabilities) in the resource mix

Strategically, it’s time to retire the notion of innovation as episodic or in parallel to every day business. Innovation (and marketing) must be part of daily business, not an add-on.

Why innovation must be continuous

A Seeker’s progress origins and progress sought are constantly evolving:

- progress sought becomes more ambitious as Seekers are influenced by their other progress attempts and what they observe in other domains or industries

- progress origin evolves as Seekers gain reusable capabilities from other progress attempts.

And in the background, externalities – who insert elements into a Seeker’s progress sought to protect Seekers and society – also evolve there constraints.

Together, these dynamics render static propositions obsolete. Capabilities that once felt distinctive become common. Frictions once tolerated become deal-breakers. What was once desirable becomes insufficient.

Helpers must continually revisit what “progress” looks like from the Seeker’s view – not their own. Competitors, including the Seekers themselves, are continuously improving their ability to reach progress sought. Standing still is falling behind.

Drucker implores us: innovate or die. The progress economy shows us why. What are you doing to keep up with the ever evolving progress origin and progress sought of your Seeker(s)?

Now we know why Peter Drucker put it bluntly:

Innovate or die.

The Progress Economy shows us that’s not a slogan, it’s the operating reality.

Impact on helper organisation

Such a progress-first approach needs to be reflected in a Helper’s organisational set-up. We’ll propose that a Helper needs an individual that we’ll call a Progress Owner. They are responsible for three key activities:

- Marketing – keeping on top of understanding the changing progress origin and progress sought of the Seekers (and what competitors are offering)

- Execution – ensuring the progress proposition is executed correctly each time

- Innovation – evolving the proposition to continue to attract Seekers (and grow either the number of exchanges or size of exchanges)

A helper organisation needs more than a product owner…they need a progress owner who keeps on top of:

- execution – successfully executing a proposition

- marketing – understanding seeker’s evolving origin and progress sought

- innovation – improving the proposition

If this is the where of progress, let’s now turn to looking at the mechanics.)

Let’s progress together through discussion…