Innovation: Creating and executing progress propositions…

We make progress by performing progress-making activities in which we apply capabilities – skills, knowledge, physical abilities, natural resources, time, and so on . through the integration of resources.

Though our progress attempts falter when we lack the required capability. In fact, we may not even begin an attempt if that lack feels too great. This is the foundational progress hurdle in the progress economy.

A key observation is that capabilities are unevenly distributed amongst the actors in the progress economy. Other actors often possess what we lack. They may be willing to offer those capabilities to us in exchange for capabilities we can offer in return. We call this service exchange, and it is the basic unit of economic activity (although, most of this exchange is indirect – we are getting ahead of ourselves here).

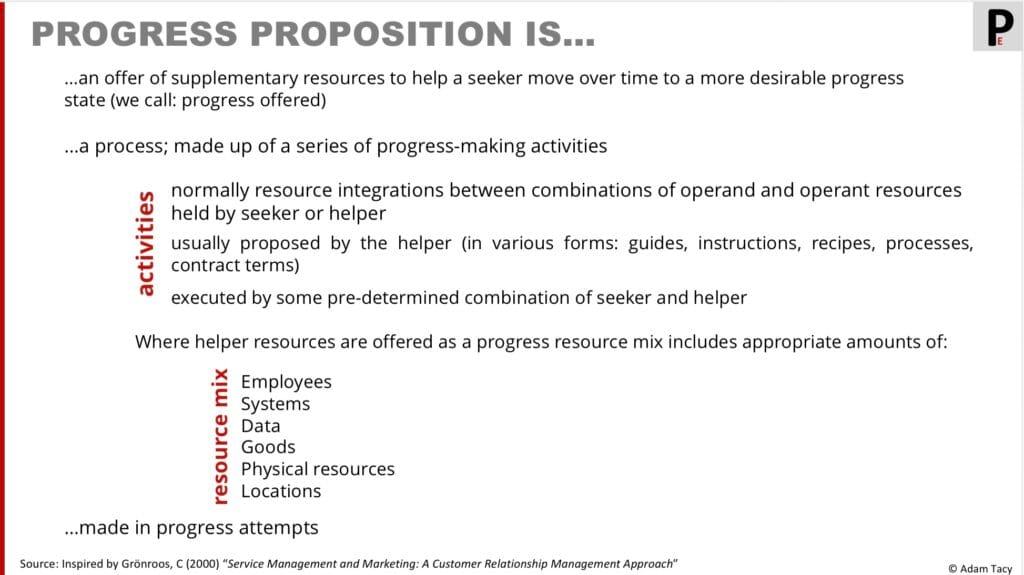

When an actor offers capabilities to help another make progress, we call them a Progress Helper, and what they offer we call a progress proposition.

These propositions are bundles of supplementary capabilities aimed at reducing the lack of capability progress hurdle. But they introduce five additional hurdles. Specifically a proposition consists of a resource mix capturing competencies and a proposed set of progress-making activities (knowledge). The mix is some proposition specific combination of employees, systems, goods, physical resources, data and locations; and you may better recognise progress-making activities as instructions, processes, manuals, or workflows.

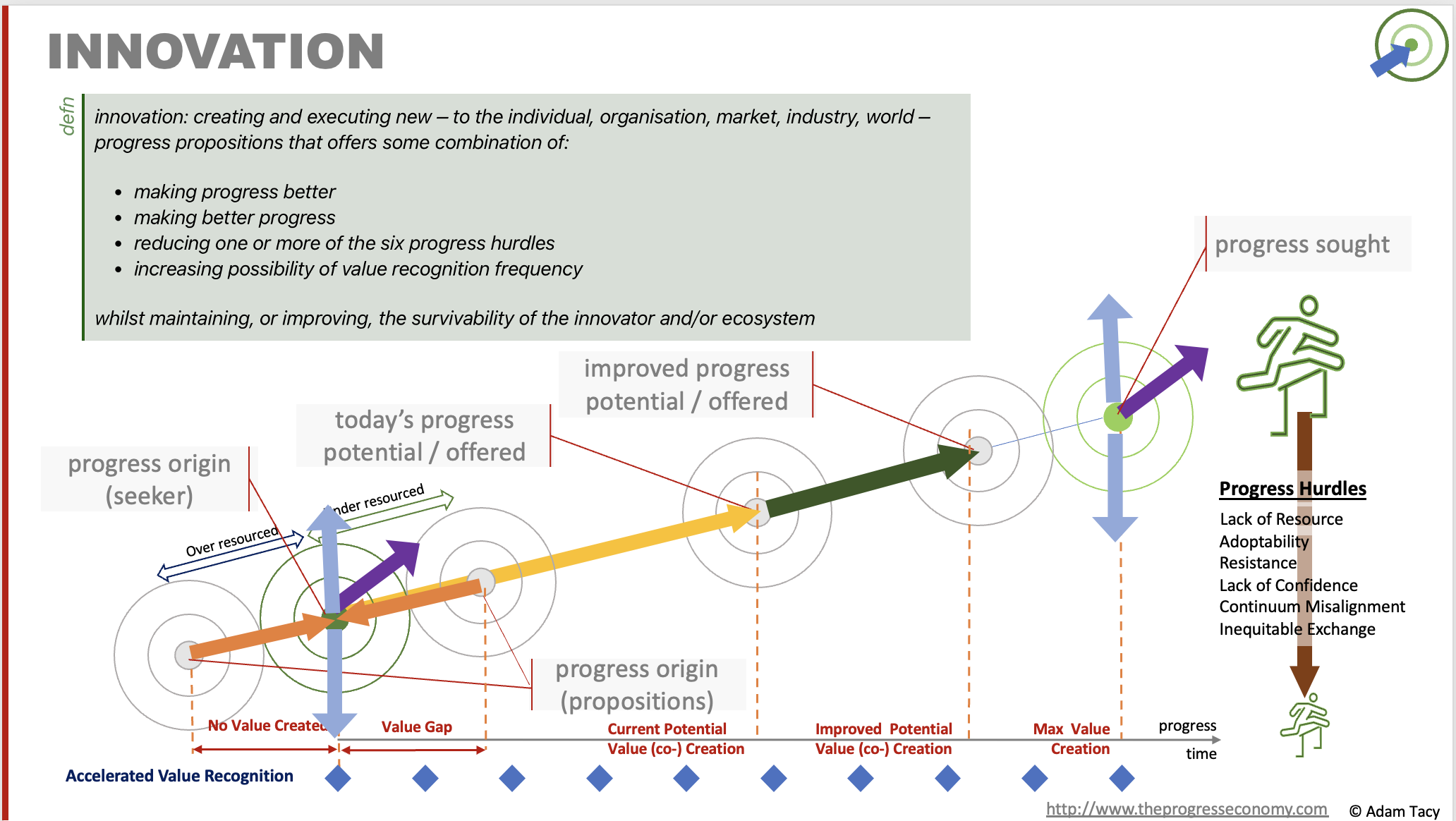

Our constant need for supplementary capabilities to make the desired progress across all areas of our lives is what ultimately drives innovation. We innovate either to help ourselves make better progress, or to offer better help to others in exchange for the capabilities we lack.

At its heart, the act of Innovation is creating progress propositions to enable better progress. That means offering a different resource mix and/or improved progress-making activities than is currently available.

Consider Peloton. It does not simply sell a bike; it combines:

- a bike (goods)

- live-streamed classes (proposed progress-making activities)

- gamified leaderboards and an online community (systems/data)

This combination appeals to Seekers looking to improve fitness (functional progress sought) in an engaging way (non-functional progress sought) while exercising at home (contextual progress) than they might with a bike out on a street on their own.

Aligning proposition journey to the Seeker’s

Here’s where the door opens to our first two innovation outcomes.

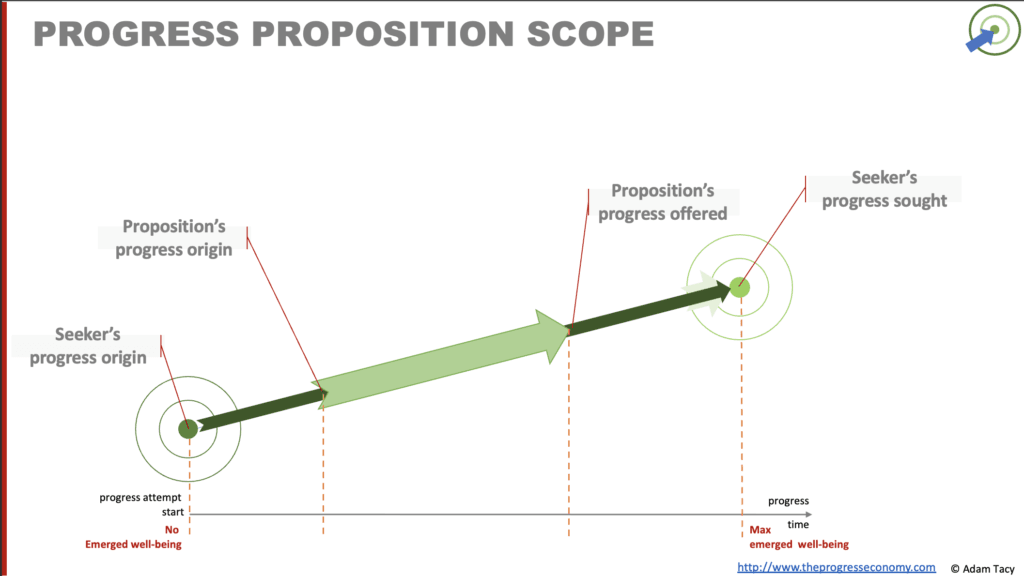

Every proposition offers a journey toward a state of progress offered, starting from an assumed proposition progress origin. Every Seeker, meanwhile, has their own current progress origin and progress sought. Rarely do these align perfectly; something we can illustrate on a progress diagram.

Innovation can often means better alignment. We can innovate to i) get the Seeker closer to their progress sought and(or ii) start the proposition’s journey closer to the Seeker’s actual origin. We may decide to extend or narrow our coverage of the journey, bundle additional propositions, or unbundle parts of our offer to create choice – as online retailers do with payment and delivery options – or even offer new propositions as Amazon did when it separated AWS (Amazon web services) from retail.

Taking Pelaton again, some gyms innovated to offer Peloton classes, appealing to those Seekers whose contextual progress sought gives a constraint that “at home” is not possible/wanted.

Because progress has functional, non-functional, and contextual dimensions, increasing “possible progress” often gets seen as better aligning functional progress, while “making today’s progress better” usually gets seen as aligning non-functional or contextual improvements. This can be a useful cognitive deceit.

Seen this way, a progress proposition’s scope becomes a powerful lever for systematically exploring innovation.

Deciding to engage a proposition

How a Seeker choses an proposition to engage opens the door to our second two innovation outcomes.

A Seeker aims to maximise well-being improvement while minimising progress hurdles and accelerating recognition of that improvement. Their decision making process unfolds as a recurring proposition engagement judgement rather than a simple purchase choice.

Before, during, and after engagement, they judge

- close to their progress sought is the proposition’s progress offered

- far do they feel they can progress with the proposition to the progress offered

- close is the proposition’s progress origin to their own current progress origin

- low are the six progress hurdles

- far have they progressed compared to their progress sought

Innovation should look to lower the progress hurdles and accelerate well-being recognition

Executing a proposition

An innovation must be executable.

However compelling an idea may be, it remains just an idea if it cannot be implemented in the real world. It cannot help anyone make progress. Idea2Value.com, found only 60% of innovation definitions they looked at includes “executing the idea”.

Time travel illustrates the point. It might perfectly satisfy a Seeker’s desire to return to the past and fix a mistake, but it does not translate into a workable proposition. At best, we can approximate the intent through more practical means — for example, by designing an “undo” function, or allowing users to delay sending an email so they can retract it. These solutions do not deliver literal time travel; they enable partial progress in a form that can actually be executed.

This brings us to a deeper question: who performs the progress-making activities?

Sometimes the Seeker wants to do everything themselves. In other situations they want the Helper to take full responsibility. Most of the time, progress emerges from a combination of both. This gives rise to what we call the enabling–relieving proposition continuum.

At one end of this continuum, propositions primarily enable the Seeker by supplying tools, capabilities, or resources while leaving most of the work with them. At the other end, propositions increasingly relieve the Seeker by performing more of the work on their behalf.

Sliding along this continuum is a powerful progress lever. It typically changes both the propsition’s resource mix and the non-functional or contextual progress it supports. This dynamic helps explain the broader “shift to the service economy” as many offerings have gradually moved from enabling to relieving propositions.

Crucially, the continuum also exposes another of the six progress hurdles: continuum misalignment. Even a strong proposition can fail if the Seeker and the Helper occupy positions too far apart. A highly relieving service will frustrate a Seeker who wants control, just as a highly enabling one will disappoint a Seeker who expects the work to be done for them.

Innovations and the propositions that embody them must also be new – but “new” is a slippery word. What, precisely, does it mean? That is the question we turn to next.

Let’s progress together through discussion…