…that are new to the individual, organisation, market, industry, or world…

Innovations must be new. Otherwise we are describing adoption or sales, even though, as we will see later, sales interactions can generate local innovations that travel upstream. Where we often go wrong is in how much “newness” we believe innovation requires.

Traditional thinking equates innovation with something never seen before. That is a mistake. Cloud-based ERP is not new to the world, but when a mid-market manufacturer adopts it for the first time—and it enables better progress than their current approach—it is innovation for that firm.

The ISO innovation standard is helpful here. It frames novelty as relative, not absolute: novelty is determined by the perception of the organisations and interested parties involved. In other words, newness is contextual, not universal.

novelty is relative to, and determined by the perception of the organisations and interested parties

ISO 56000 (2025) – Innovation Management – Fundamentals and Vocabulary

I prefer a more explicit, graduated view of novelty. Edison, bin Ali, and Torkar (2013) describe innovation as being new to different levels:

Innovations can be new to the:

Ali and Torkar’s (2013) “Towards Innovation in the Software Industry”

- firm/individual

- market

- industry

- world

At the lowest level, innovation is simply something new to a firm or even a single individual making a progress attempt. At the highest level, it is new to the world – an advance that creates entirely new possibilities for progress.

New to firm/organisation/individual

“The minimum level of novelty of innovation is that it must be new to firm. It is defined as the adoption of an idea, practice or behaviour whether a system, policy, program, device, process, product, technology or administrative practice that is new to the adopting organisation”

I also add new to individual here, reflecting that the innovator could be a single Seeker.

New to market

“When the firm is the first to introduce the innovation to its market”

New to industry

“These innovations are new to the firm’s industry sector”

New to world

“These innovations imply a greater degree of novelty than new to the market and include innovations first introduced by the firm to all markets and industries, domestic and international”

Breakthroughs like CRISPR gene editing or early quantum computing sat at that “new to the world” frontier. They did not just improve existing progress; they made previously impossible progress possible – curing certain genetic diseases, or solving optimisation problems that classical computing could not feasibly handle.

Over time, such breakthroughs rarely stay confined to that top tier. They diffuse outward, becoming new to markets, industries, and other firms as organisations discover fresh applications.

A logistics company using annealing quantum computing to optimise complex, dynamic routing; a construction firm adopting digital twins originally developed in aerospace; or the payment industry adopting QR codes from part tracking, are not inventing new science. They are innovating by carrying powerful ideas into new contexts where they meaningfully improve progress.

Carrying innovation from one market/industry to another – A progress lever

This diffusion points to an important managerial insight: one of the richest sources of innovation is not invention, but transfer. Leaders should actively ask what other firms, markets, and industries already do well that could reshape progress for their own stakeholders.

Seekers do not experience your organisation in isolation. Their expectations are shaped by progress they achieve elsewhere, and they increasingly expect to make progress in your market/industry in ways they can in others.

According to den Hertog, consultants often facilitate this process (Knowledge-Intensive Business Services As Co-Producers Of Innovation). Because they operate across many sectors, they act as carriers of innovation, moving practices from one domain to another.

Predictive maintenance began in aerospace, where reliability is existential, and was later carried into manufacturing, logistics, and energy infrastructure. Agile methods emerged in software and have migrated into hardware design, marketing, and even strategy. The QR code followed a similar path – born in manufacturing, carried across industries, and then exploding into retail, payments, transport, and healthcare once the public encountered it.

Relation to Adopter types

I mentioned how as innovations diffuse they move down the novel categories. It is tempting to map that directly onto Rogers’ classic adopter types: innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority, and laggards.

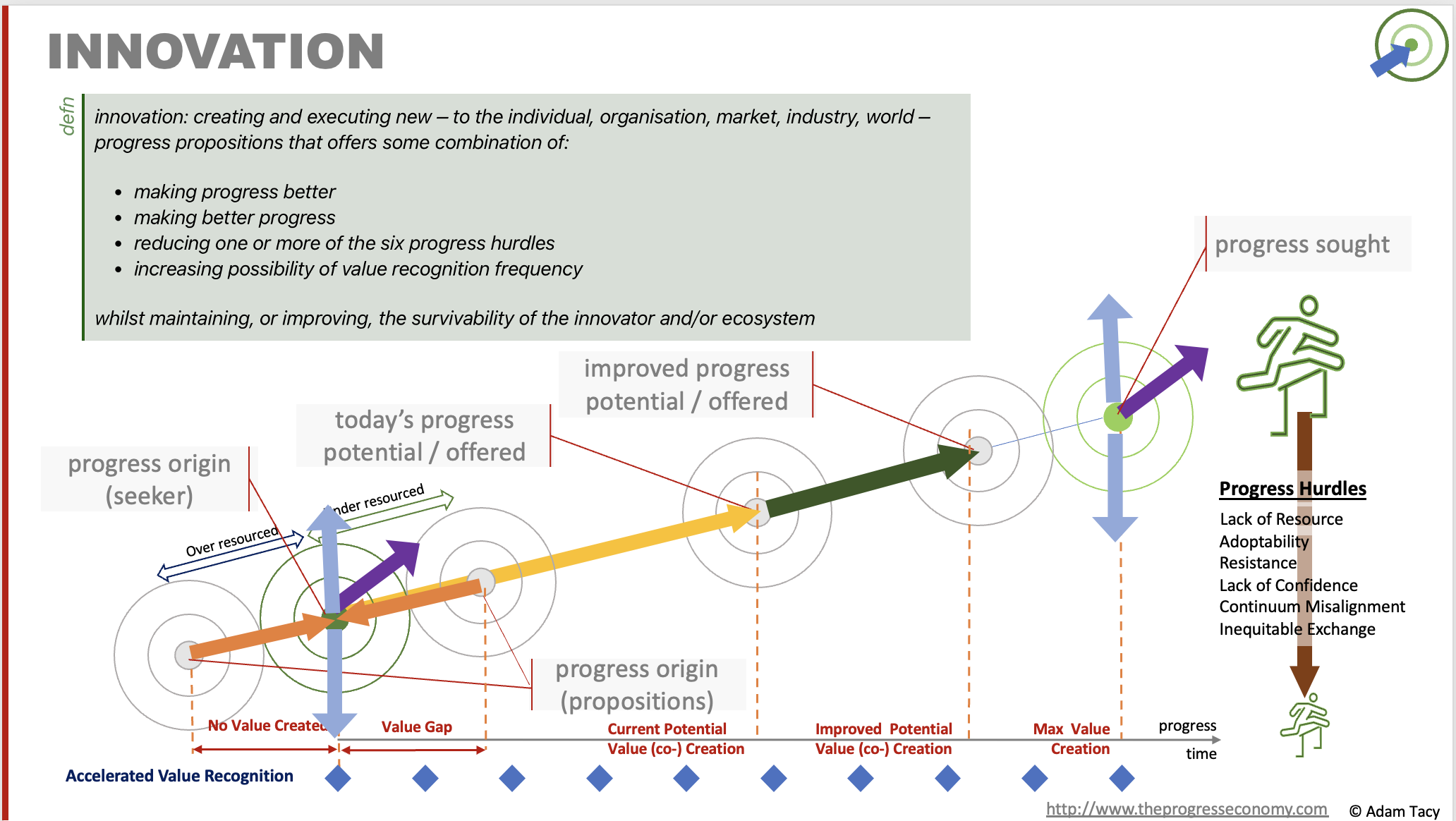

Those categories are valuable. They offer deep insight into the psychology of adoption, the forms of marketing likely to resonate, and the conditions that accelerate uptake. Indeed, these dynamics surface in the progress economy as one of the six progress hurdles: adoptability.

But mapping adopter types directly to novelty is misleading. An innovation that is well established in one market, let’s say is being adopted by the late majority, may still be highly challenging to adopt in a different market/industry. It may once again require innovators and early adopters to lead the way.

Innovation diffusion is a fascinating topic, I have more about it over here.

What does new mean? – A progress lever

Firms can innovate by upgrading existing resources—better technology, more capable systems, or employees with greater autonomy and skill. They can innovate by altering the resource mix, replacing physical goods with digital ones, or substituting standardised products with human service. And they can innovate by redesigning the progress-making activities, making the journey simpler, faster, or less burdensome for the Seeker.

Stripe illustrates this clearly. It did not invent payments; it removed technical and contractual hurdles that had made online payments slow and complex. By lowering friction in the progress journey, it allowed businesses of any size to begin transacting in hours rather than weeks.

| component | discussion |

|---|---|

| upgrading a resource in the resource mix | existing resources in the resource-mix can be upgraded, be it a goods or system that is improved (more effective, more aligned with Seeker expectations), or employees further trained or given more flexibility to act etc ➠ |

| altering the resource mix / sliding along progress continuum | you might decide to innovate by swapping out one or more aspects of the resource mix for other aspects – goods with employees for example; or physical goods by digital goods. ➠ the “shift” to a service economy |

| updating the progress-making activities | process innovation has a home here when you look to innovate the progress-making activities. Are you making things easier/simpler for your Seeker (end customer/internal customer), can you reduce cost etc ➠ Stripe lowered the cost of online payments (through removing the technical and contractual hurdles) , allowing businesses of any size to start taking payments in hours instead of weeks |

Seen this way, “new” is not a mystical category reserved for laboratories and moonshots. It is a practical managerial choice: how will you reshape resources, activities, and journeys so that Seekers can make better progress?

So, innovations are propositions that are new to an individual, firm, market, industry or the world. However, to be attractive to a Seeker – and gain the service exchange the Helper needs – they need to offer to improve the Seeker’s well-being. That is the subject we look at next – the four innovation outcomes.

Let’s progress together through discussion…