Stop asking “What product should we build?” and start asking “What capabilities do our customers lack that hinders them making progress they seek, and how can we package those into the resource types they are looking for?”

Savvy leaders unlock sales, innovation, and growth by repeatedly and purposefully aligning their proposed resource mix and progress-making activities with ever evolving Seeker needs. Seekers don’t stand still – neither should your proposition.

What we’re thinking

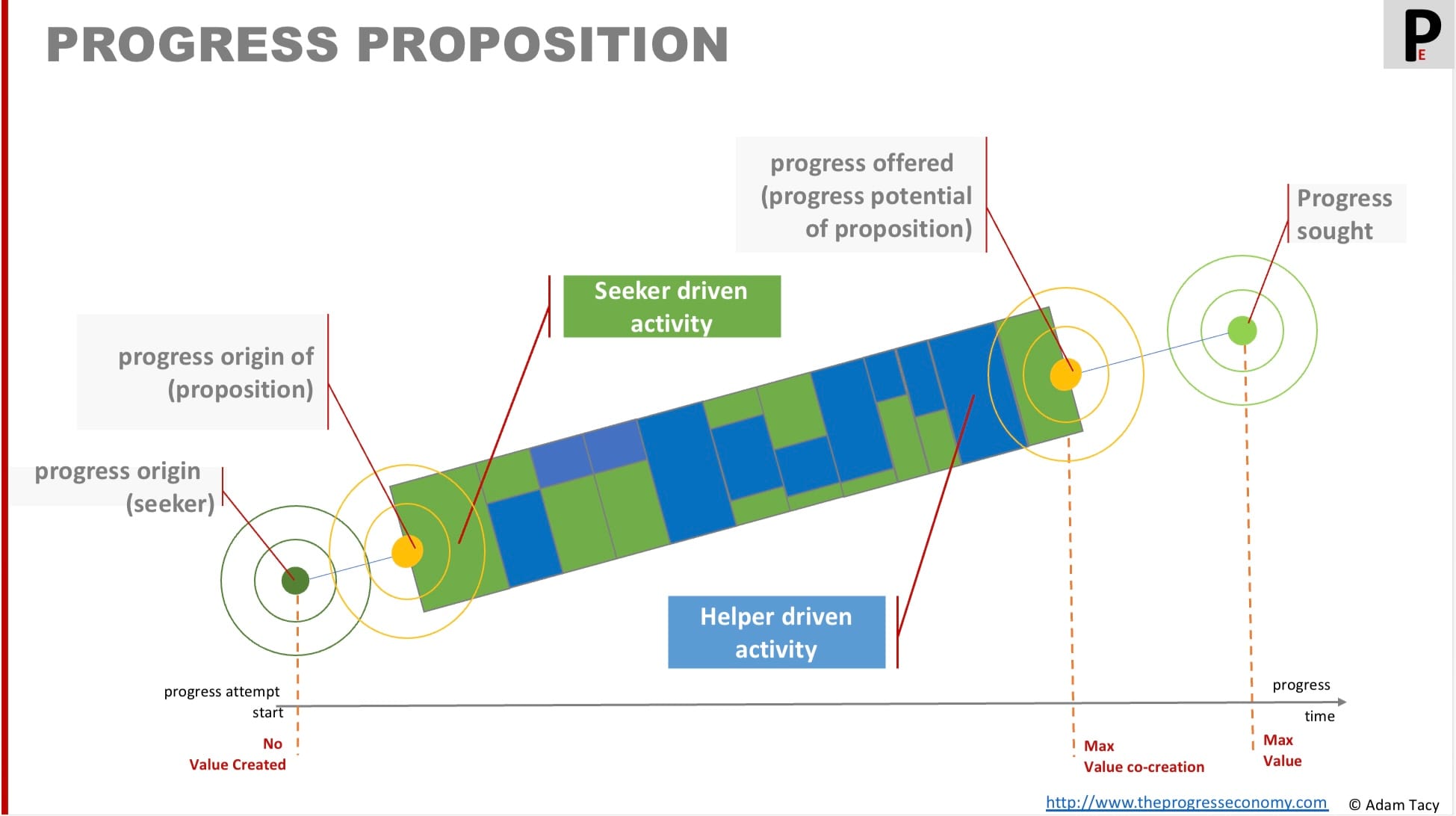

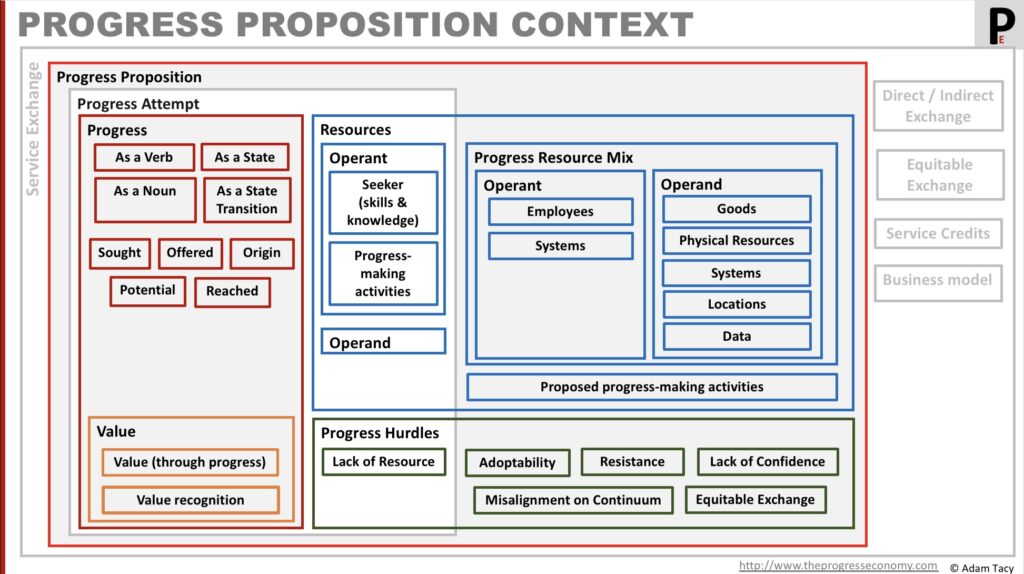

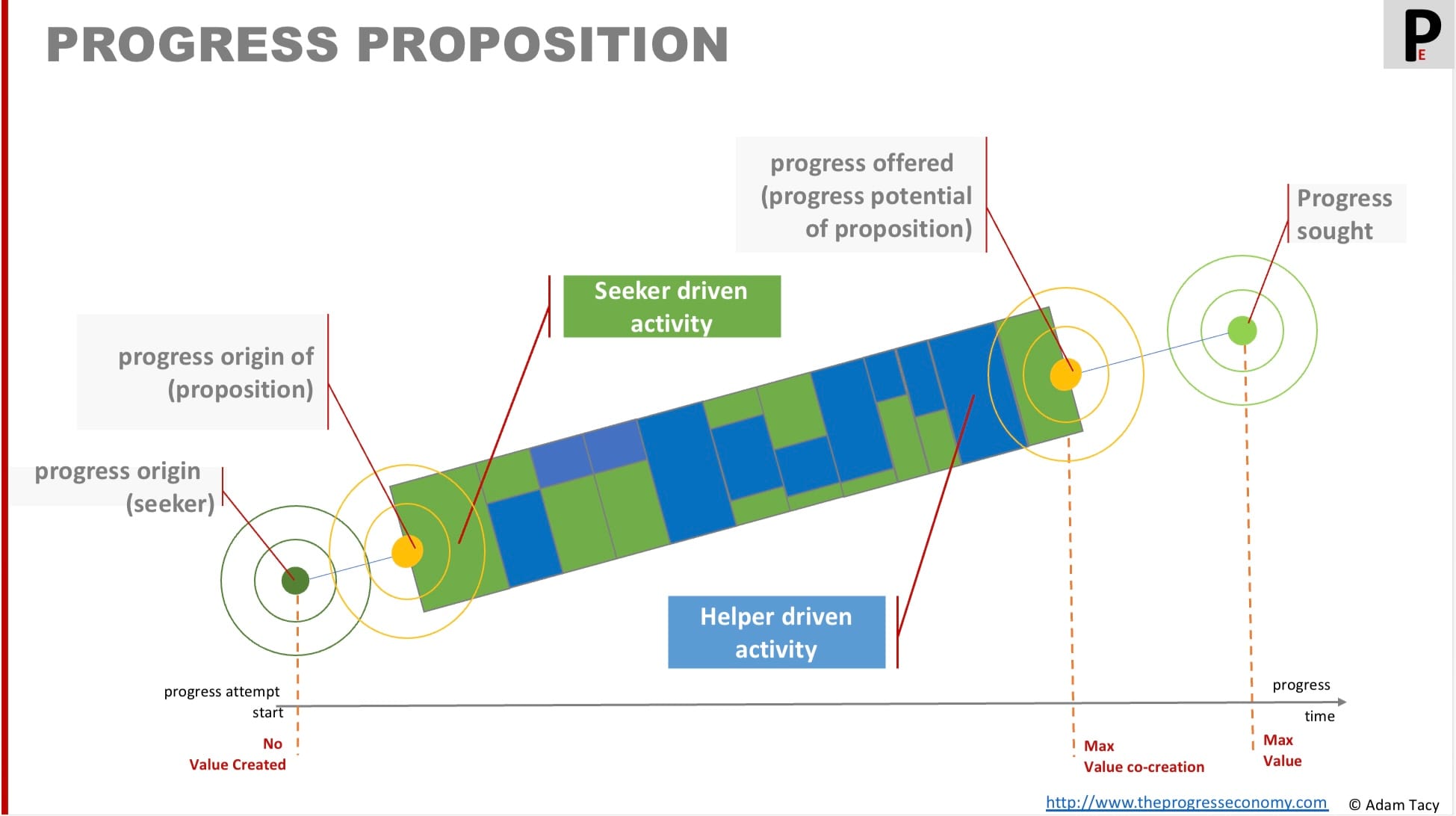

When Seekers can’t reach their progress sought due to a lack of capability, they usually turn to progress propositions – offers from Helpers that provide supplementary capabilities. Each proposition contains a:

- proposed series of progress-making activities

- curated resource mix carrying offered capabilities

Ideally, the proposition mirrors the Seeker’s unique journey – matching both their progress origin and progress sought. But deep customisation comes at a cost. The more tailored the offer, the higher the equitable exchange (for simplicity: price), often limiting adoption at scale.

In reality, most Helpers offer pre-defined journeys. Seekers must assess whether the proposition’s progress offered aligns with their progress sought, and if its origin is close enough to their own. Some propositions might offer limited tailoring. This introduces is to segmenting a proposition’s progress origin and offered by progress. If no single proposition covers the full journey, Seekers must stitch together multiple propositions – creating opportunities for Helpers to bundle propositions (or even unbundle).

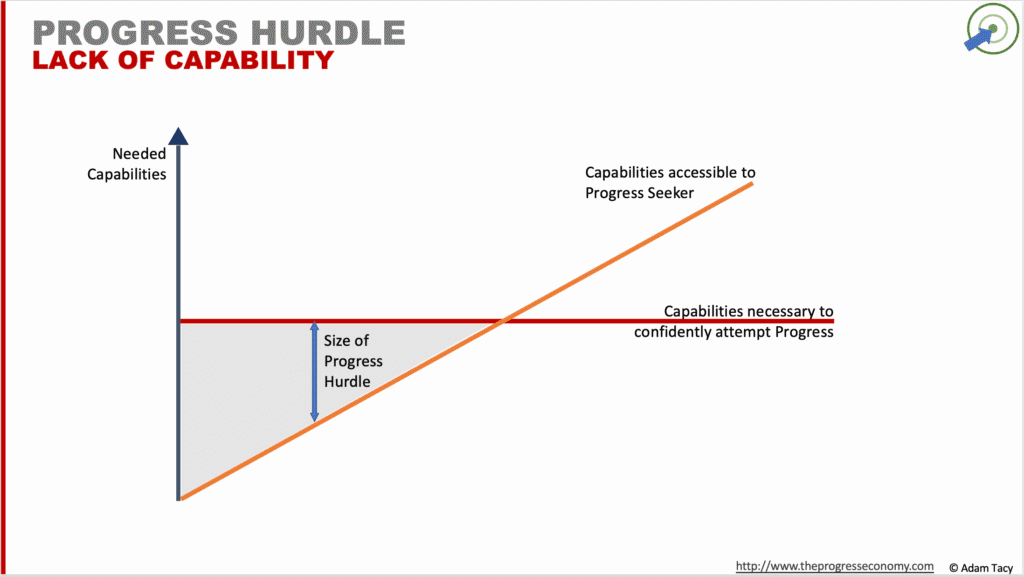

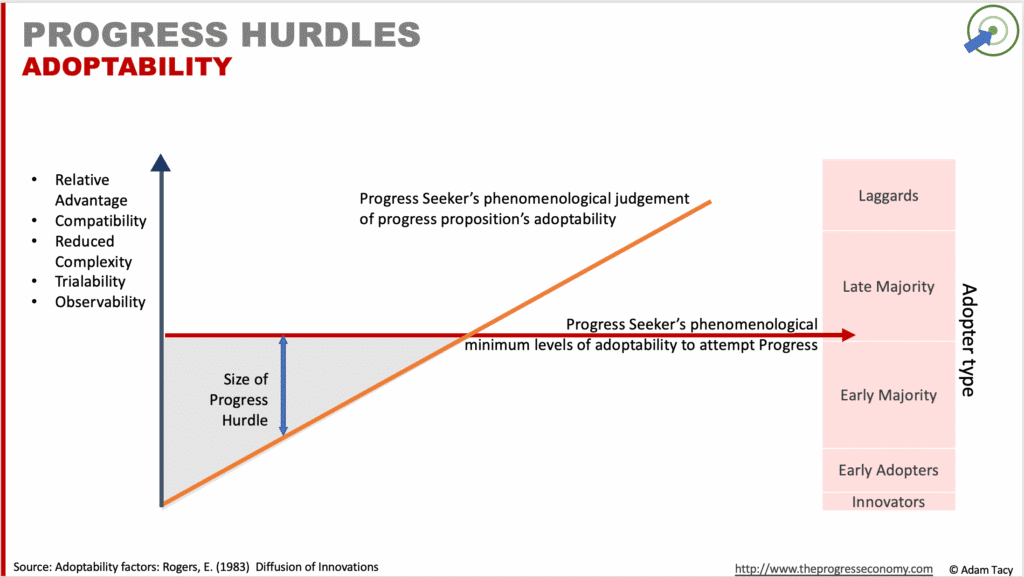

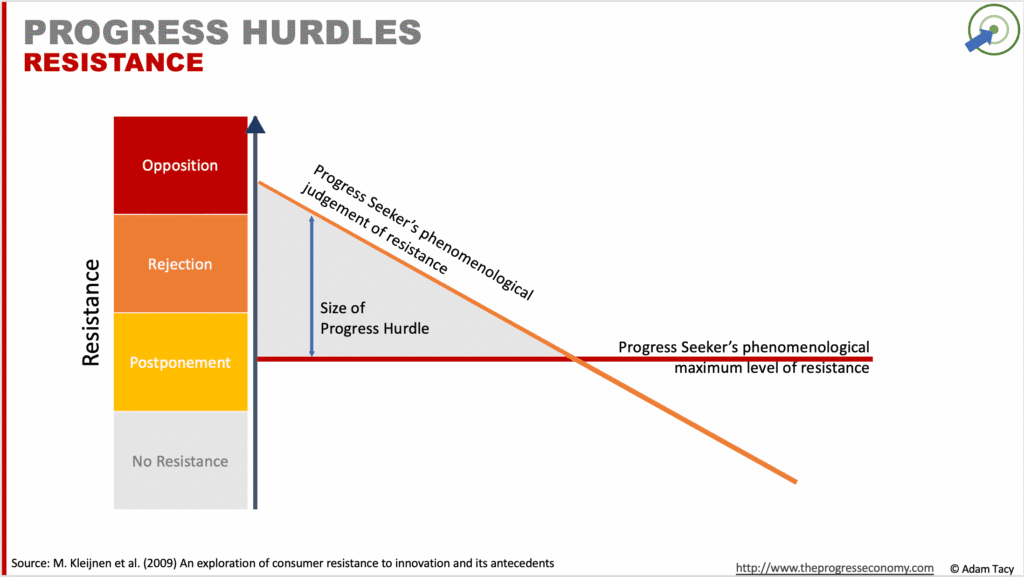

Though propositions address capability gaps, they also introduce five new hurdles: continuum misalignment, inequitable exchange, adoptability, resistance, and lack of confidence. Minimising these frictions is critical. Helpers that do so increase uptake.

Strategically, propositions extend the progress attempt into a shared endeavour. Who leads – the Seeker or the Helper – in executing the progress-making activities determines the offer’s position on the enabling–relieving continuum. Misalignment here can undermine even well-resourced propositions.

Seekers still rely on a structured decision process, but now evaluate not only progress potential, but progress fit, and the additional hurdles introduced by the proposition itself.

Editing below here

Progress Propositions

progress propositions: bundles of supplementary capabilities aimed at helping a Seeker make progress from a specific progress origin to a state of progress offered.

Think of progress propositions as how Seekers attempt to make progress when someone is providing them with supplementary capabilities to reduce their lack of capability progress hurdle. Don’t forget that whilst a Seeker tries to make progress with everything in their life, we usually concentrate on particular aspects of that progress sought at a time.

Progress becomes a joint endeavour and a proposition may even increase the Seeker’s progress comparison of progress potential against progress sought (part of the view of value). However, a proposition may not align directly with a Seeker’s progress sought nor origin (ie it may not fully reduce the lack of capability hurdle). A Seeker needs to judge if it is sufficiently close in order to make the attempt.

What are progress propositions?

Propositions are offerings of supplementary capabilities with the aim of helping a Seeker make progress. Specifically, they provide supplementary capabilities as two bundles, a:

- proposed series of progress-making activities – better known as instructions, manuals, recipes, processes, etc

- progress resource mix – proposition specific mix of six types of resources carrying the offered capabilities

We should note that propositions have no inherent value, only potential value. As Grönroos writes:

It is of course only logical to assume that the value really emerges for customers when goods and services do something for them. Before this happens, only potential value exists

Grönroos (2004) “Adopting a service logic for marketing”

Progress propositions are service; and maybe direct (as we casually imagine service is) or indirect (frozen into, say, goods).

Relationship to service

In our traditional view of the world (goods-dominant logic), we see services (plural) – an output. And we see them as the poor relative to goods. We create an artificial, and unhelpful, goods vs service debate. But service-dominant logic, on which we build the progress economy, evolves this perspective.

From service-dominant logic we’ve evolved our definition of service (singular) as:

service: the application of capabilities for the benefit of oneself or another party

And this is what progress propositions are: the offer to apply some defined capabilities for someone’s benefit.

Grönroos’ definition of service gives us some additional foundations we will build upon.

He describes service as consisting of two key elements, a:

- series of interaction activities

- set of service provider elements – employees, goods, physical resources and systems.

These will become our proposition’s proposed series of progress-making activities and resource mix (which has a few more elements than Grönroos identifies).

Service, and by extension, progress propositions, can be delivered directly or indirectly.

Direct service involves the immediate application of a Helper’s capabilities, typically through human effort or digital systems. These are what we call relieving propositions, as they take effort away from the Seeker. Indirect service is different. Here, capabilities are frozen into goods, distributed, and later unfrozen by the Seeker through acts of resource integration. These are enabling propositions, supporting the Seeker in doing the work themselves.

We’ll revisit this distinction when we examine progress-making activities, it’s a crucial one. Whether a proposition relieves or enables affects the Seeker’s experience, effort, and perceptions of value. But let’s take a Quick Look at goods.

Role of goods

Goods are a form of indirect service. They freeze capability, capturing skills, knowledge, perhaps strength and others, so it can be distributed across time and location. A Seeker then unfreezes that capability when performing a act of resource integration.

Take a screwdriver: it encapsulates the manufacturer’s knowledge and skills (capabilities) to engage with and turn a screw. The Seeker integrates their own strength and knowledge – choosing the right tool, applying the right force – and progress is made. The screwdriver doesn’t act on its own. Goods are operand resources, and must be acted upon for progress to be made.

The world is now a much richer place of goods than that of simple progress attempts. There, goods were limited to what a Seeker could find or create in their immediate environment. Now, goods also include any indirect service a Seeker acquires through the current progress proposition or from prior progress attempts.

Importantly, goods are just one type of capability-carrying resource, alongside, for example, people and systems. This equivalence is strategically powerful: it enables resource substitution. If different resources carry equivalent capabilities, they can be swapped within a proposition. This opens up the solution space and avoiding Levitt’s classic marketing myopia.

As Levitt observed, customers don’t want a quarter-inch drill; they want a quarter-inch hole. That outcome could be delivered by a drill, by another tool, or from a handyman, or other methods altogether. When you view goods through this lens, you begin to see new ways to design more innovative, modular, and adaptable propositions.

Some propositions may offer only goods in their resource mix. But in practice, those goods are often wrapped, by the Helper or through other parties, into broader service systems. A car comes through a dealership. DIY tools come with distribution, support, and sometimes instruction whether in-store or online.

This layered integration reminds us: even when we buy “things,” we’re still navigating service ecosystems. And that insight helps leaders rethink what they’re actually offering and what customers are really seeking.

Putting propositions in the strategic context

Here’s how progress propositions fit into the context of the progress economy. They build upon progress attempts context, adding the progress resource mix, the proposed progress-making activities, as well as introducing 5 additional progress hurdles.

Let’s explore the key components of progress propositions, starting with progress offered.

Seeker’s progress origin and progress sought

inherit from progress attempts, including that they evolve over time. that leads to Drucker’s famous call to action:

Innovate or die

P. Drucker via “Innovation on the fly”, HBR

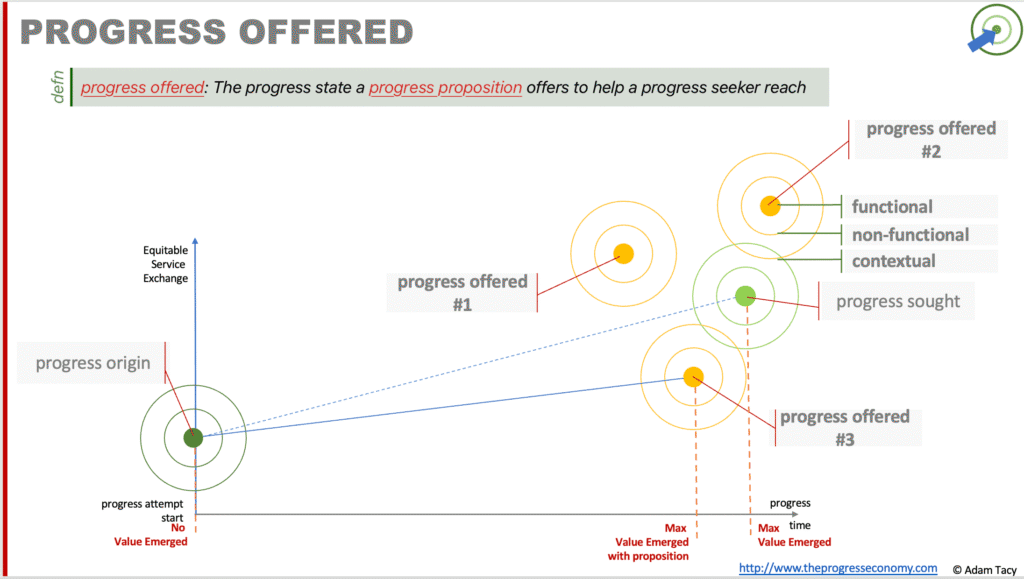

Progress offered

A helper’s proposition aims to help a Seeker reach a state of progress offered.

progress offered: The progress state a progress proposition offers to help progress seekers reach

And, like all progress states, progress offered comprises functional, non-functional and contextual elements. Each element matters to the Seeker and becomes critical in their progress comparison (shaping their perception of value) as they weigh what’s being offered against the progress they seek..

Seekers typically focus on specific aspects of their broader progress sought during any given attempt. That focus is unique to both the Seeker and the attempt. As a result, full alignment between a Helper’s progress offered and a Seeker’s progress sought tends to be either coincidental or the result of deliberate customisation.

But customisation comes at a cost. The more a Helper tailors a proposition, the more effort they must invest. That raises the required equitable exchange (for simplicity: price). As equitable exchange requirements rise, the proposition can become less attractive to the Seeker.

To manage this, successful Helpers adopt a strategic segmentation approach – one that focuses not on demographics or product features, but on distinct aspects of progress sought. By doing so, they can offer propositions that resonate with broader patterns of demand, and that Seekers are wiling to compromise in progress reached. Such an approach still allows Helpers to offer limited customisation. In some cases, other Helpers may offer that customisation, filling the gap. Seekers may assemble a chain of propositions to make their journey (or the Helper can do so – think delivery services in e-commerce – or offer suggestions).

aligning to progress sought matters

Here’s how 3 progress offered states look if plotted on our standard progress diagram, their relation to a Seeker’s progress sought, and the impact on value as perceived by the Seeker.

When the progress offered aligns precisely with the Seeker’s progress sought, we assume maximum potential value. But perfect alignment is rare. Often, propositions offer progress states that either:

- Fall short of the Seeker’s goal

- Extend beyond what the Seeker originally intended

Offering less progress than sought obviously obviously means progress (potential value) is left on the table.

Whereas offering more progress than the Seeker seeks can sometimes be an unexpected advantage, opening up additional progress (value). But it may also be irrelevant or increase progress hurdles the Seeker isn’t willing to overcome. Christensen’s disruptive innovation (innovator’s dilemma) plays out here – Seekers may trade down to simpler, lower cost, new technology propositions that meet their needs “well enough”.

Alignment as Sales

Helpers use the sales process to convince a Seeker that the offered proposition is best at helping the Seeker reach nearest their progress sought.

It’s a place where some customisation may occur. It’s also a place where “in process” innovation may occur.

But progress offered is to the only important progress state in a proposition and a Seeker’s judgement of that proposition. Where the proposition offers to help from is often equally important.

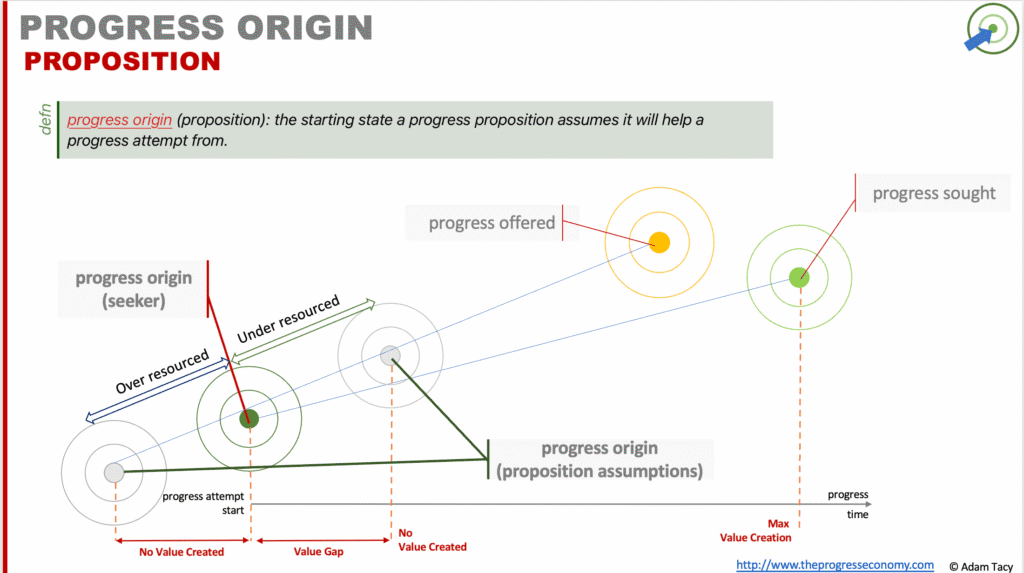

Progress origin

A Helper’s proposition also makes an assumption about where the Seeker is starting their progress attempt. This is an aspect that is often forgotten or missed. It informs the capability and resources needed by the Seeker.

We have two definitions of progress origin, one for each of the actor’s viewpoints:

progress origin (seeker): the attempt specific progress state from which a progress seeker begins a progress attempt.

progress origin (proposition): the starting state a progress proposition assumes it will help a progress attempt from.

When these origins misalign, even the best propositions can fall short.

Aligning to seeker’s progress origin matters

Here’s a visualisation of a progress proposition’s origin not aligning with a Seeker’s.

Your proposition’s origin could be to the right of the Seeker’s. Imagine a beginner aiming to learn Mandarin Chinese, but the only available proposition assumes they are already at an intermediate level. The Seeker lack of resource has not been sufficiently reduced by the proposition. The effect is to reduce the Seeker’s progress potential vs progress offered progress comparison

On the flip side, a proposition may assume the Seeker is starting from further back than they actually are. This creates friction:

- It wastes the Seeker’s time with unnecessary steps.

- It may inflate the equitable exchange (the Seeker is asked to exchange effort for resources or activities they don’t need).

- If progress-making activities are made mandatory rather than optional, frustration quickly compounds.

Consider a Seeker who already speaks a tonal language but wants to learn Mandarin. If the only course available forces them to spend six weeks on tonal basics, they will quickly disengage.

Handling progress origins strategically

Progress origin is not just a customer experience detail, it’s a segmentation opportunity and a design imperative.

You must:

- Segment your propositions by progress origin, just as you would by progress sought.

- Ensure your proposition’s starting assumptions match the Seeker’s real starting point.

This is already common in industries like education – Mandarin courses are often structured around beginner, intermediate, and advanced levels, typically aligned to the HSK syllabus, which serves as a proxy for progress measurement.

The key question to ask: are you over-offering or under-offering relative to where your customers really are?

Over-offering increases cost and friction. Under-offering leaves unmet needs and risks abandonment. Alignment is what

Proposed Progress-making activities

This is reflected in service-dominant logic thinking:

All social and economic actors are resource integrators

One resource Seekers may lack is knowledge of the necessary progress-making activities. A proposition proposes the activities to be perfored to reach progress offered from the proposition’s progress origin. These align with the offered resource mix and resources the proposition expects the Seeker to have.

You may be more familiar with these proposed activities if we call them:

- instructions

- operating manuals

- recipes

- processes

- contract terms etc

We inherit the concept of progress-making activities from progress attempts, except:

- this series of activities is proposed by the progress helper

- activities are performed by some combination of the seeker and helper

- resource integrations are some combination of seeker resources and supplementary resources in the proposition’s progress resource mix.

Each progress-making activity remains an act of resource integration.

Proposed series of activities. Can be missing for the Seeker. Not necessarily mandatory. Can be encoded into a system, that makes them mandatory. Relieving propositions can hide the activities internally giving commercial protection. Enabling propositions hide skills and knowledge within the frozen goods, but need to give proposed progress-making activities to the Seeker, ie how to use the goods.

This aligns with the concept seen in a progress attempt, where a series of progress-making activities is undertaken; this time to achieve the progress offered, judged by the seeker as sufficiently close to their progress sought.

In contrast to progress attempts, progress propositions introduce key distinctions:

Here’s how the difference between a progress attempt with and without a proposition looks like.

In our daily lives we encounter these proposed activities under more familiar names, such as:

- instructions

- operating manuals

- recipes

- processes

- contract terms etc

These proposed activities are often not mandatory for the seeker to follow. Seekers can opt to use their own devised activities. When was the last time you unboxed a new electrical device and read the manual before using? Although a helper may embed the activities within a system or outline them in a specific contractual manner to enforce their usage.

Just like with progress attempts, this series of progress-making activities is an operant resource; as such, service-dominant logic tells us they are a source of strategic benefit. The quality of the proposed activities directly influences progress and, consequently, the emergence of value.

resource integrations

Service-dominant logic’s 9th foundational premise tells us that all actors are resource integrators:

All social and economic actors are resource integrators

#9

And this is exactly what we see In the progress economy. Both our main actors, seekers and helpers, integrate resources in order to make progress. For example:

- a patient (seeker operant resource) providing background information to a doctor (helper operant resource)

- a teacher (helper operant resource) educating a student (seeker operant resource)

- a customer (seeker operant resource) driving a hire car (helper operand resource)

- a technician (helper operand resource) repairing an object (seeker operand resource)

resource integration – a model

We can also build a model for how resource integration works. Luckily Gallouj & Weinstein (1997) provide such a model to which we can make some very simple tweaks. Below you can see this.

The intention being the final characteristics (far right) are what the seeker experiences. We can interpret those as the aspects of progress sought (or offered) elements. The functional, non-functional and contextual elements. They are achieved through various resource integrations between the items in the rest of the diagram.

The technical characteristics are the operant resources that when acted upon lead to aspects of progress. These are the goods, physical resources, data, locations, processes, systems (operant), and the series of progress- making activities.

On the left we find the skills and competences of the seeker and any helper employees and systems acting as operand resources.

Gallouj & Weinstein identify interesting aspects. Particularly that beneficial characteristics in helper employees are often captured as technical characteristics to ensure they are shared amongst other employees.

Who performs the proposed progress-making activities

When a Seeker engages a proposition, progress becomes a joint endeavour. Either the Seeker, the Helper, or both will drive the progress-making activities, each contributing capabilities. This remains a process of resource integration, as previously defined, but now the lead operant resource maybe more than just the Seeker.

Some propositions, known as enabling propositions, place the responsibility for progress-making fully on the Seeker. They must integrate their own and the supplementary resources to make progress.

Other propositions, known as relieving propositions, shift this responsibility to the Helper, who performs all progress-making activities and integrates their own resources with those of the Seeker.

Most propositions exist somewhere along a spectrum – the progress proposition continuum – ranging from fully enabling to fully relieving.

Whilst we say the progress-making activities are proposed, there are two subtleties. First, the Helper might make them mandatory – for example through embedding them in.a system, or requiring that through terms and conditions. Secondly some of the progress-making activities can be hidden from the Seeker – something that really relates to propositions towards the reliving end of the continuum.

Aligning continuum expectations

Crucially, it is the Seeker who drives the preference for enabling or relieving propositions. As Helpers, we can aim to understand these preferences and shape propositions to match. When there is a mismatch between what a Seeker desires and what a Helper offers, the height of the continuum misalignment progress hurdle increases. Minimising this misalignment is a key factor in making a proposition attractive.

Protecting

How does a Seeker “capture” value?

Progress resource mix

6 types of resources that a Seeker integrates with – not all are required, it is specific to proposition.

- Employees (operant): humans, or AI, that Seeker interacts with

- Systems (operant or operand)

- Data (operand)

- Goods – both physical and digital (operand)

- Physical resources – goods where ownership is temporarily transferred (operand)

- Locations (operand): specialised places where progress is made, eg hospitals, platforms, web sites

Not every resource type needs to be included in a particular mix; a single item like a nail can serve as a straightforward, one-item resource mix.

Here’s a couple of example mixes, in a useful way to visualise them:

The composition of the resource mix often sheds light on the nature of the proposition, indicating whether it leans toward enabling or relieving on the proposition continuum.

Altering the mix

Modifying the resource mix is feasible because resources carry capabilities, making them largely interchangeable, though not necessarily in a one-to-one ratio.

For instance, substituting an employee with a goods – such as a tradesman with a hammer – is a toy example of this interchangeability. Goods have the ability to freeze knowledge and skills, enabling their distribution, and are unfrozen during acts of resource integration.

This substitution not only shifts the proposition’s position on the continuum, now leaning towards enabling rather than relieving, but it also affects the supported non-functional requirements. Additionally, it places specific resource demands on the seeker, requiring knowledge, skills, and time, as illustrated in this example.

Introducing additional Progress Hurdles

Whilst the intention of propositions is to address the lack of resource progress hurdle, they may not do so fully. And they may even create a new, different, lack of resource hurdle.

Say, for example, to meet a functional progress of travelling between cities, we offer fly yourself mini aircraft. We might offer a way of attempting progress. But we require the seeker to have skills and knowledge of flying the aircraft – likely a resource they lack.

The mere presence of a progress proposition brings about five additional hurdles that must be minimised.

We have to ensure the seeker feels they can use the proposition. For example it is simple and they can trial it. If you’ve studied innovation then this is Rodgers’ adoptability. And we need to minimise seekers deciding to resist the proposition. Think back to the resistance to nuclear power stations of the past.

| hurdle | description |

|---|---|

| adoptability | can the progress seeker easily envision themselves using the proposition? (Rogers adoption factors) |

| resistance | will the progress seeker resist, postpone, reject, or oppose the proposition due to perceived risks, usage conflicts, traditions, norms, or image concerns? |

| continuum misalignment | how far apart on the progress continuum (enabling to relieving) are the proposition and what the seeker is looking for? |

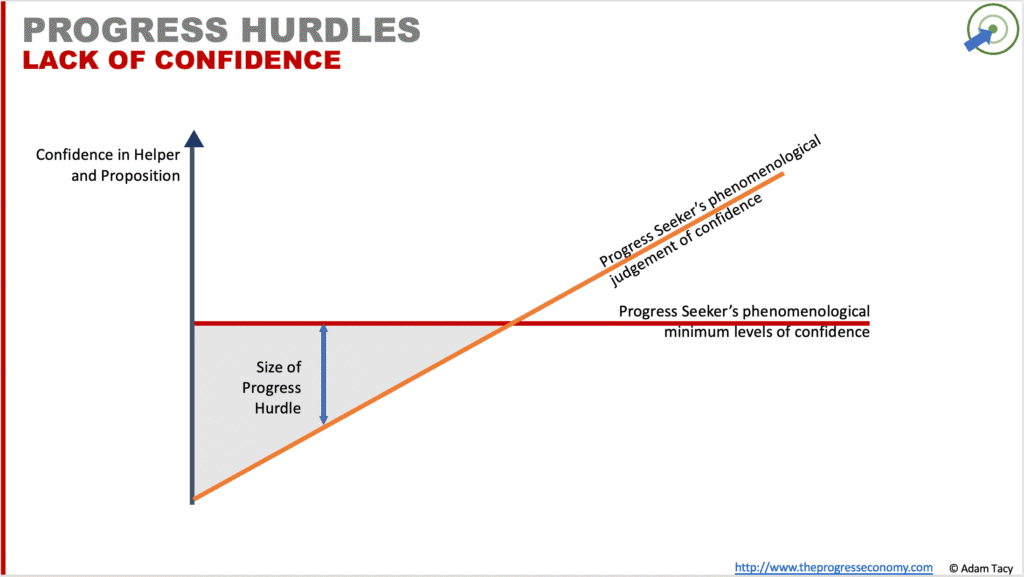

| lack of confidence | does the seeker trust the proposition and the helper behind it to assist them in reaching the offered progress state? |

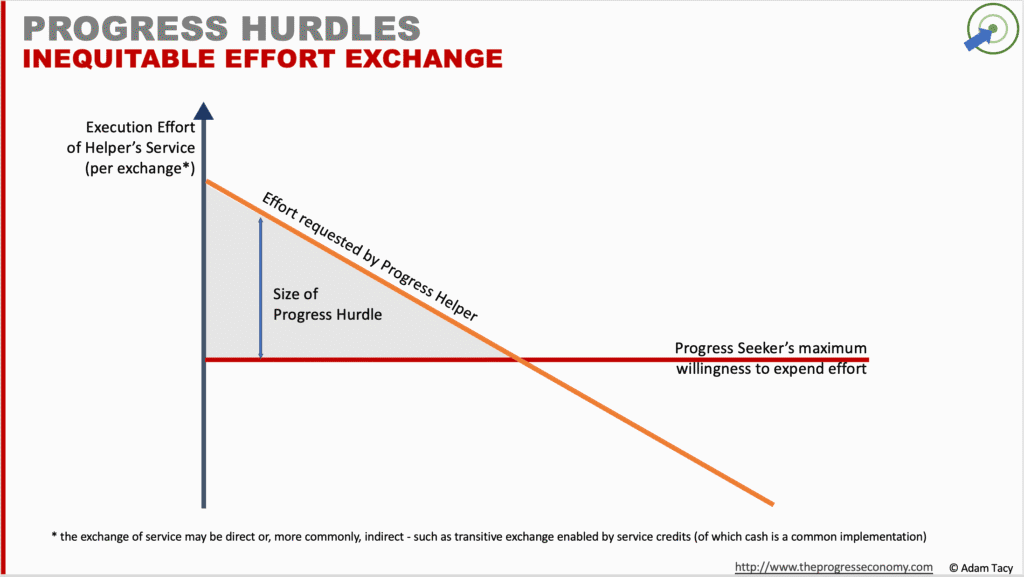

| inequitable exchange | how many service credits (ie effort given in service elsewhere) does a progress seeker need to engage the proposition |

Yet another challenge emerges based on the position of the proposition along the continuum we’ve previously discussed. It turns out seekers also position themselves on the continuum when making a progress attempt. They may be looking for non-functional progress that is supported by a relieving proposition. If you’re offering only an enabling proposition, then you are far from what they are seeking.

The seeker’s confidence in your proposition and in you as a helper becomes important. Lower confidence means a higher barrier.

Lastly the seeker needs to feel they exchange of service they are about to partake in with you is equitable. Given most exchanges are indirect, the question the seeker is asking themselves is this: does the effort I need to give (or have given) in providing service elsewhere justify the effort I’m going to get from you.

Lastly, the seeker needs to feel that the exchange of service they are entering with you is equitable. Are they getting enough effort from you for the effort they are giving in return. Since most exchanges are indirect, seekers question is really are you asking for too many service credits for your help.

Updating the progress decisions process

When engaging a proposition the seeker follows a slightly updated decision process. Now they also need to judge if the progress offered aligns closely enough with their individual progress sought.

We call this updated approach the proposition engagement process. Which you can compare to the earlier progress decision process below.

Now the start and continuation decisions include phenomenological decisions by the seeker on

How Seekers Judge Propositions

Before a Seeker engages a proposition, they make three critical progress comparisons:

- Progress offered vs. progress sought: Will this proposition get me close enough to my goal?

- Progress potential vs. progress offered: How close do I believe I can realistically get using this proposition?

- Progress hurdles vs. Seeker’s hurdle profile: Are the hurdles low enough for me in this attempt?

As Seekers progress, they continuously reassess whether to continue based on their evolving experience of progress achieved vs. expected progress and recompiling the above.

It is these comparisons that feed into the concept of value in the progress economy. The proposition the Seeker scores highest on the above, ie helps a them make the best progress, will be perceived as most valuable by the Seeker.

Let’s note a couple of things. First, a proposition has no value itself, only the potential to help progress.

actors cannot deliver value but can participate in the creation and offering of value propositions

#7

Second, whilst we see the Seeker as predominantly judging value (progress comparisons) we differ from our service-dominant logic foundation that finds them exclusively doing so. In certain propositions, Helpers actively evaluate whether a Seeker is likely to succeed before granting access to their supplementary resources. This is particularly relevant when the Helper’s resources are scarce, the risk of failure is high, or an element of non-functional progress is exclusivity.

Misusing Propositions: Value destruction

Deviating from the suggested steps can be viewed as a misuse of resource, or lead to misusing other resources. That potentially leads to value co-destruction.

What drives helpers to offer propositions?

Helpers are not usually alltruistic, offering their resources for nothing. They are, though, also Seekers, pursuing their own progress that they likely lack the necessary capabilities. This progress may be something they desire directly, or it may be as a result of how they offer capabilities to Seekers (assembling progress from other Helpers), or internal as a result of their operational structure (an R&D capability requires resources that are essentially helpers on their own).

That motivates them to engage in service exchange. It’s a “I help you and you help me” dynamic. However, this is not a barter economy – which Martin tells us in Money, the unauthorised biography didn’t and don’t really exist. These exchanges are rarely direct, which is why we might not notice them in our day to day observations. Service-dominant logic, one of our foundations, tells us:

Indirect exchange masks the fundamental basis of exchange

#2

In most cases, exchanges are indirect and asynchronous, creating a need for mechanisms that can balance differences in magnitude, timing, and parties involved. That mechanism is service credits, with cash being a widely adopted and highly effective implementation.

The number of service credits a Helper requires is a signal of effort a Helper requires from a Seeker in return for giving access to their resources. We’d all like exchanges to be equitable, ie we’re not expending more effort than we’re getting in return (directly or indirectly). Here we find the inequitable exchange progress hurdle. But we also find business model innovation – exchanges may be one-off, or a series (subscription) or subsidised (eg advertisement based); or even “funded” by another party (frictionless payments, bank loans…).

Creating propositions

Fundamentally, new propositions emerge when an actor finds ways to either make progress better or make better progress. This appears as improvements in the progress-making activities, changes to the progress resource mix, or both.

Sometimes these improvements are discovered accidentally. Other times, they surface during the aligning phase of sales conversations. But more often, they are the deliberate outcome of focused research, development, and innovation activities.

It should be noted that a key reason many innovation initiatives fail is their lack of disciplined focus on what will actually be useful to Seekers. The progress economy solves for this by offering a laser focus on progress as the anchor for sales, innovation and relevance.

Since propositions are themselves resources, the ways we discover them align with the same mechanisms by which Seekers and Helpers find other valuable resources:

- observation/imitation: by observing others making progress attempts (from own and other market/industires)

- finding in environment:

- experience: hands-on involvement in progress attempts

- experimentation/innovation: using resources available to them, or combining them, in new ways; or creating new resources

- education and training: taking formal education and training programs to acquire specific capabilities (eg skills and knowledge from a teacher, or strength from weight training)

- acquiring/collaborating with: other helpers

- from other exchanges they are involved in

Relating to innovation

Payne tells us the following about helper competitiveness:

If a supplier wants to improve its competitiveness, it has to develop its capacity to either add to the customer’s total pool of resources in terms of competence and capabilities (relevant to the customer’s mission and values), or to influence the customer’s process in such a way that the customer is able to utilize available resources more efficiently and effectively

Payne, A. F., Storbacka, K., and Frow, P. (2006) “Managing the co-creation of value”

Which touches the two resource bundles of a progress proposition:

- progress resource mix – “add to the customer’s total pool of resources in terms of competence and capabilities (relevant to the customer’s mission and values)”

- proposed progress-making activities – “influence the customer’s process in such a way that the customer is able to utilize available resources more efficiently and effectively”

Innovation should focus on creating new, or altering existing, progress resource mix and progress-making activities so that a proposition offers some combination of:

- increasing a seeker’s progress potential (getting them closer to their progress sought)

- improving how to make existing progress better

- reducing one or more of the progress hurdles

By segmenting they look at both functional and non-functional aspects. That feeds directly into Porter’s Generic Competitive Strategies (differentiation vs cost). That is to say, helpers look at mainstream progress and decide which components can be decreased (cost) and which can be increased (differentiation). Supermarket self checkouts are a good example of getting this wrong.

Expanding on that, a helper can also add or remove progress components to the mainstream view. Now we’re talking about the main tool in Kim and Mauborgne Blue Ocean Strategy, aiming to identify markets that are uncontested.

Let’s progress together through discussion…