Forget value. It is your well-being you increasingly improve as you seek to make progress towards your progress sought. Discover the actionable model that will accelerate your sales, innovation and growth.

What we’re thinking

We’re breaking free from the traditional confines of value and value creation to tackle our innovation and growth challenges head-on.

Instead of fixating on value, we focus on what truly matters to seekers: increasing their well-being through making progress toward their more desirable state.

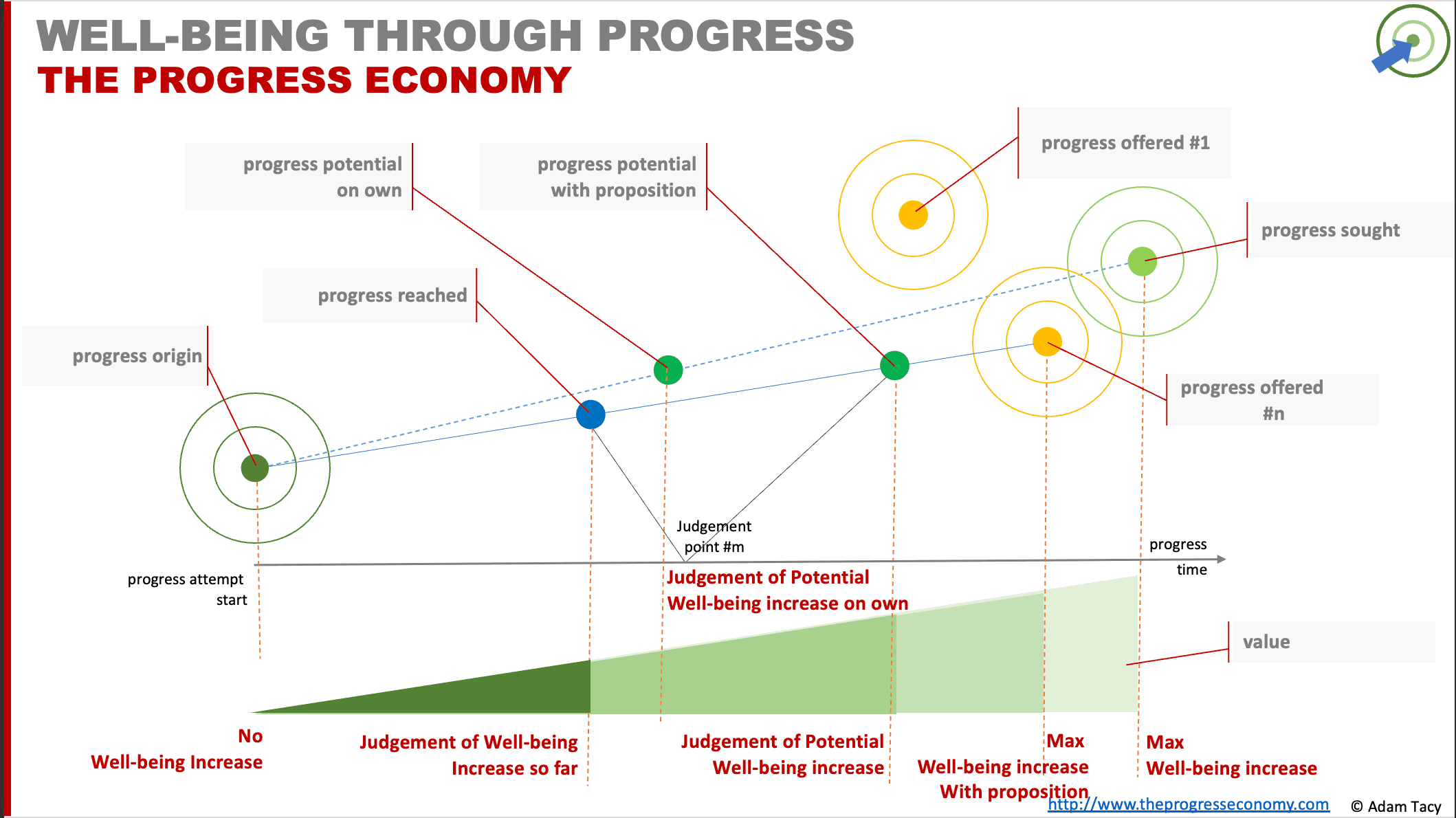

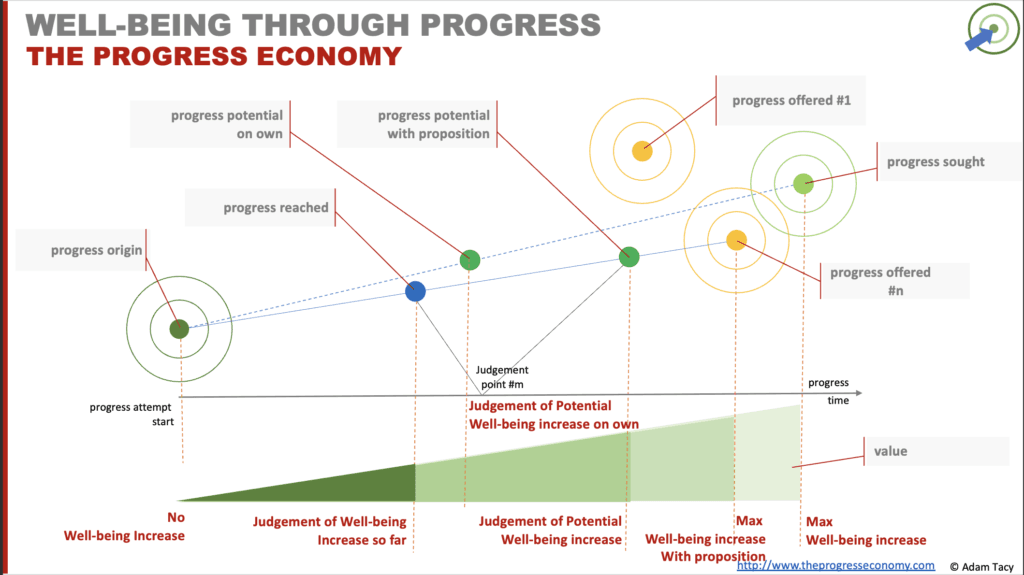

Well-being is phenomenologically judged – before, during and after a progress attempt – primarily by the Progress Seeker through comparisons of progress – potential increase, emerged increase, recognised increase. Where the maximum increase in well-being is felt when progress reached matches their more desired state of progress sought.

Conceptually, well-being progressively increases as progress is made towards progress sought. For it to be meaningful to the Seeker, emerging increase in well-being needs to be periodically recognised by them (similar to how revenue is recognised in accounting).

Why this matters

This model advances three key aspects:

- Well-being is not value – it cannot be exchanged, but increasing it is what Seekers want to do

- Progress is the actionable language into how well-being is increased

- Change in well-being is judged as comparisons of progress

Since we are building out the vale-in-use model, we inherit its benefits over the traditional value-in-exchange…then super-charge our thinking through our alternative focus on progress.

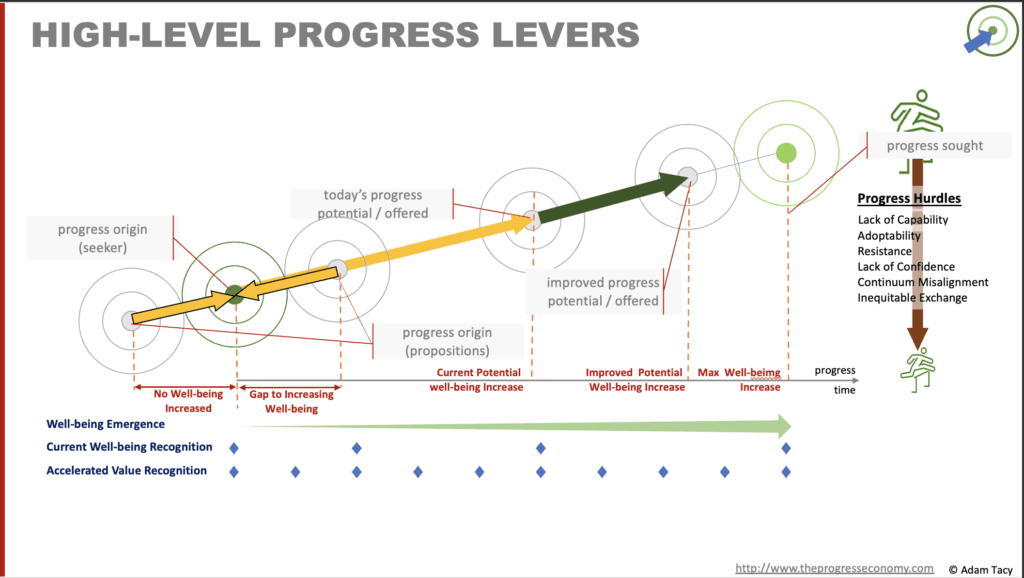

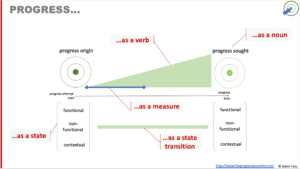

Progress is a state, a noun, a verb, and state transitions. Through understanding it, we can build an operating system of our world. Identifying levers such as progress origins, progress sought, progress offered, progress-making activities, progress hurdles (such as lack of resource), supplementary resource mixes offer us the ability to systematically improve progress (innovation).

Updating to better reflect well-being instead of value

Key concept: Well-being increases from making progress

Now we arrive at the progress economy’s model of value – or rather we get to see why we need to drop the idea of value, and how we do that. We’ll build on the value-in-use model, so we inheriting how that addresses the growth blind spots in our traditional value-in-exchange model.

Value-in-use introduced us to well-being, and that value comes from increasing well-being. Creation, or co-creation, of value happens during a process rather than being an output. But it gives us no definition as to what well-being is, not how we actionably increase it.

although it wIt turns out that a focus on “value” is putting the cart before the horse, as the saying goes. Instead, we pivot our focus to what truly matters: progress – a verb, state, noun, and state transition. Progress is:

moving, over time, to a more desirable state

The observation is that:

increases in well-being emerge from progress being made towards progress sought.

There is no value is created (or emerges, as I prefer to say) before progress is attempted. As progress is made, value progressives emerges, with maximum value emerging when the seeker reaches their more desirable state. Although value may be destroyed along the way if progress stalls or reverses.

In this model, we name a number of key progress states, as well as observing that a progress state comprises three aspects: functional, non-functional and contextual. This provides us the levers to better understand progress and to improve it

Value becomes the comparison of actual and expected progress (actually several comparisons as we’ll see) made before, continuously during, and after a progress attempt.

These various progress comparisons come together to inform us that judgements of well-being act as both a:

- trailing indicator of progress reached – how far have I reached?

- leading indicator of potential future progress – can I get where I want?

If one, or both, are not sufficient in the eyes of the progress seeker then they’ll see the progress attempt as less valuable and they may either not start, or abandon, it. We’ll call the progress comparisons made by a progress seeker as value judgements.

With an eye on making progress we’ll observe that there are progress hurdles. These are aspects that a seeker may feel hinder them from progressing. The fundamental hurdle is a lack of resource. Progress helpers arise offering supplementary resources packaged as progress propositions. Their aim is to minimise lack of resource and help a seeker progress. Though a proposition introduces five new hurdles, as we’ll see.

Our model also recognises a progress helper may make their own, independent, progress comparisons relating to progress with a specific progress seeker. Those comparisons may result in the helper withholding, or withdrawing, access to their proposition.

Uniquely to this model, we’ll also recognise that emerged value may not be immediately meaningful to a seeker. They need to recognise value – a process akin to revenue recognition for any accountants reading. This recognition often happens slower than continuous emergence. For example at the end of an activity, or even not until all progress sought is made.

Welcome to the value-through-progress model. It has the following benefits and constraints:

benefits

- inherits all benefits from value-in-use

- defines a clear, actionable, definition of progress/value

- enables the nature of value to be understood and harnessed

- explains market fit and markets/ecosystems

- enables the construction of a 4-layer operating system of progress

- restores a link to price – shining light on business model innovation

constraints

- value is complex to understand

- helpers are complex (individual ecosystem…)

- progress and value are often uncountable

- easy to over apply the inherent need for interactions

Leveraging a model that focuses on progress leads to clearer reasoning about desires, mechanisms, decision processes and hinderances to making progress. These are the levers for more systematic innovation.

Before we delve into how we define, create, and measure progress, along with its implications for innovation, let’s first briefly explore what progress means.

What is progress?

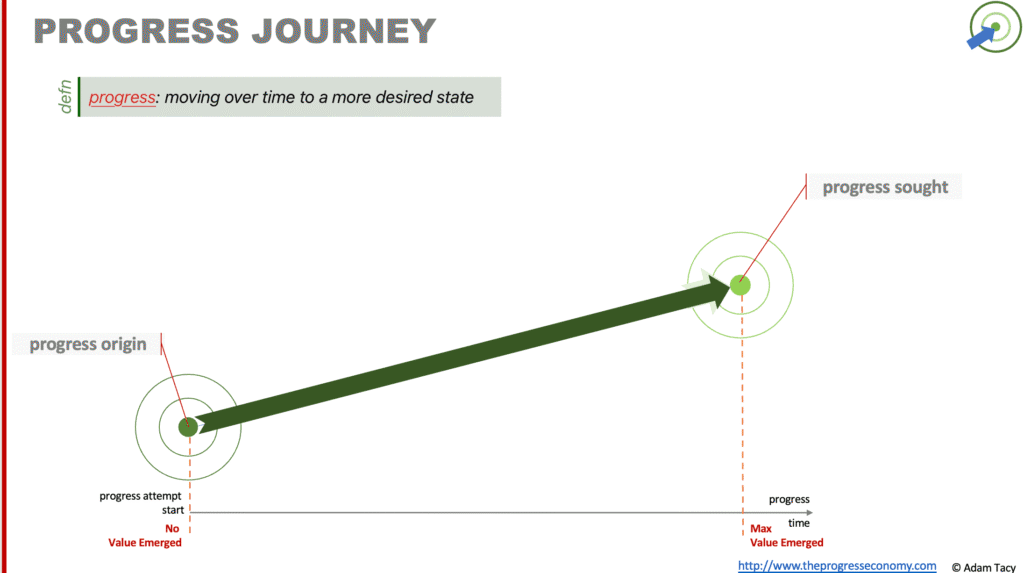

At its core, progress is a verb, a move over time to a more desirable state.

progress: moving over time to a more desirable state

Perhaps we want to speak Mandarin Chinese, or arrive in another city, or have a picture hanging on a wall, or fill some time on a rainy Monday evening. These are desired progress states, which we name as a seeker’s progress sought. Where a seeker starts their progress attempt from is the state we call their progress origin.

Importantly, progress states capture more than just the functional progress such as learning Mandarin. They also capture non-functional, and contextual aspects. Together, the three aspects give us the best view of progress, and therefore opens our eyes to what seekers see as success.

As an aside, when I draw diagrams of progress, such as above, my intention is that progress increases from left to right, i.e. over time. The height of progress states is simply aesthetic.

Conceptually, we can also view progress as a series of state transitions from progress origin to progress sought. Hanging that picture on the wall, for example, functionally involves marking the desired height, making a hole, securing a wall mount, hanging the picture.

All of which leads us nicely into understanding how progress is made.

making progress

Progress is made by performing a series of progress-making activities known as a progress attempt.

Each of these activities is an act of resource integration. That is, applying one resource to another – you (a resource) hit the nail of the wall mount (another resource) with a hammer (yet another resource) resulting in it being secured to the wall.

Resources are carriers of capabilities like skills, knowledge, and physical attributes such as strength. You carry those capabilities. Goods freeze capabilities. Time is another resource, its capability is availability. Be careful here: resources and capabilities are often used interchangeably, for example skills being seen as a resource rather than a capabilty carried by a resource. That’s not something we can fix.

We find resources come in two categories: operant and operand.

Operant Resource*

acts on other resources resulting in progress being made

Operand Resource*

need to be acted upon for progress to be made

* definitions adapted for the progress economy from Constantin & Lusch’s 1994’s book “Understanding Resource Management: How to Deploy Your People, Products and Processes for Maximum Productivity“.

Operant resources, such as you, are the primary type in this model since they drive progress by acting on other resources. Whereas operand resources, such as goods, need to be acted upon for progress to occur. The hammer and nail above had to be used by you otherwise they’re just sitting there doing nothing (except offering potential value).

Who attempts progress? It is the progress seeker. By default, they set out to make solo attempts.

This requires seekers to have access to the necessary resources. Seekers struggle to progress if they lack those resources – skills, knowledge (including knowledge of the necessary progress-making activities), tools, time, physical attributes such as strength, etc, etc. Note that here’s an example of what I mentioned above, where we mix between resource and capability in English. We call this a progress hurdle, specifically the lack of resource progress hurdle.

It is a hurdle, not a barrier. Seekers may attempt progress despite their unique and phenomenological view of the hurdle’s height compared to their unique and phenomenological tolerance of the hurdle. One seeker with a low tolerance of lack of resource may decide a hurdle of a particular height is too high to attempt; another with a more medium tolerance might decide to make an attempt anyway. Naturally, higher hurdles lower the probability of a successful attempt.

We’ll come across this “phenomenological” word a lot – simplistically it means a person’s past experience plus current situation. It helps explain your view on supermarket self check-outs and why it is different to your friend’s/colleague’s/relative’s.

This lack of resource hurdle is the fundamental hurdle in our model / the progress economy as a whole. Addressing this hurdle is where progress helpers step in.

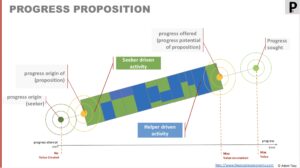

progress helpers and their propositions

Progress helpers – individuals, organisations, ecosystems – offer progress propositions: offers to help make progress. They intend to address the seeker’s lack of resources by offering bundles of supplementary resources, namely:

- a proposed series of progress-making activities – you might better recognise as instructions, manuals, recipes, ways of working, contracts etc

- a progress resource mix – proposition specific mix of external facing resources intended to be integrated with seeker’s resources (see box)

Engaging a proposition turns making progress into a joint endeavour between a seeker and the helper. This is something that is often called value co-creation.

Now, though, progress is from the proposition’s origin to progress offered by the proposition. Those two states may differ from the seeker’s origin and their progress sought.

These two progress/value gaps are judging by the seeker before engaging a proposition. The larger the gaps, the lower the judged value.

The question of why helpers do not always offer full customisation arises. Afterall, this is what appears best from above and aligns with Vargo & Lusch’s call:

the normative marketing goal should be:

- customisation rather than standardisation

- to maximise customer involvement in the creation of value

Vargo, S., Lusch, R. (2004) “The Four Service Marketing Myths”; Journal of Service Research; Vol 6; Issue 4; pp 324-335

To answer this, we need to understand the dynamics of seeker-helper relationship.

Seekers, as we’ve seen, are looking to make progress. They often lack the resources needed, and so turn to helpers for supplementary resources. What encourages helpers to offer those resources is they are seekers of some (other) progress themselves. They are looking to participate in service exchange.

Exchange can be direct – they do something for you and in return, you do something for them – but more often is indirect, lubricated by service credits (of which money has been a successful implementation). Either way, effort exchanged should be equitable. That is to say, I want service (direct or indirect) from you that has what I feel is similar effort in it as the effort in the service I give to you. As a helper, I’ll signal my effort expectation as price (effort * number of instances).

These expectations of effort exchange lead to a new progress hurdle: the equitable effort exchange hurdle.

It is that hurdle which brings us back to why helpers do not offer to customise every service. It takes additional effort to do that customisation; which raises the price, which raises the equitable effort exchange hurdle height. That potentially lowers the number of seekers choosing to engage. Which reduces the exchanges the helper participates in.

Helpers may alternatively offer a proposition that has an origin and progressed offered that is sufficient to attract enough progress seekers. They should segment based on combinations of progress origin and progress sought. This is clearly better than segmentation approaches such as demographics.

This gives us an insight into Porter’s Generic Competitive Strategies (differentiation vs cost).

Equitable effort exchange is, in fact, one of five additionalprogress hurdles that are introduced by a proposition. The other five are listed on the left.

They may struggle to be adopted, or even be resisted, by a seeker. Or a seeker may not have confidence in the proposition or the helper.

Or the proposition may sit too far on the proposition continuum from where the seeker is positioned. For example, they may be looking for a relieving proposition but your proposition is enabling. Where a proposition sits on the continuum also informs us how likely the progress helper makes various progress comparisons, as we‘ll see later in our exploration.

Finally, propositions may not sufficiently, in the eyes of the seeker, address the original lack of resources. Or may even introduce new lack of resource – for example, a flying car proposition may require the seeker to acquire and use new skills. A usable proposition will offer ways to minimise that (having the car auto-fly, for example).

Before we jump into our value model, let’s remind ourselves of the role of goods that taking service-forward logic as a foundation gives us.

remembering the new role of goods

Since we’re building on service-forward logics we should remember that goods have a new role. They freeze service provision, allowing for it to be distributed in time and space. Service is unfrozen through acts of resource integration involving the goods.

Goods are distribution mechanisms for service provision

#3

The music example I used in value-in-use is useful to summarise here.

In our model we see no difference between listening to your favourite band live in a concert or as a digital stream (or CD, record, 8-track…). The former is a service – application of skills and competence for your benefit. The others freeze that service onto digital/physical form. That form can then be distributed to wherever and whenever you integrate it with a playback device.

The benefit of this view is we lose the growth constraining goods vs service debate from value-in-exchange.

Right, it’s time to get into the comfy sofa, grab your favourite drink, and start exploring how we arrive at the above diagram by looking at how progress is made, how value emerges, and why that emerged value needs to be recognised for it to be meaningful. Buckle up, understanding value through progress is complex, but ultimately, rewarding!.

Value-through-progress

We start our view of value-through-progress model firmly routed in Grönroos’ comment that also formed the basis of value-in-use:

It is of course only logical to assume that the value really emerges for customers when goods and services do something for them. Before this happens, only potential value exists

Grönroos (2004) “Adopting a service logic for marketing”

The challenge, as we saw in both previous models, is that value is hard to define. Defined in value-in-exchange as “the highest amount someone is willing to pay” is not helpful in finding systematic levers to increase it. Value-in-use’s definition as “an increase in well-being” is slightly better, but still well-being is tricky to define, and finding levers for increasing not much easier.

I propose that our focus should be on progress, both understanding and improving it. Progress is more clearly definable and actionable. The key insight is that a seeker gets maximum value when they reach their progress sought. Working back from there we can map the other progress states we are interested in to various levels of value.

By definition, there are three fixed points we come across in a progress attempt (a move from seeker’s progress origin to their progress sought):

- zero value has emerged before a progress attempt starts

- maximum value has emerged when a seeker reaches their individual progress sought

- maximum co-created value has emerged when a seeker reaches a proposition’s progress offered

There are also three waypoints on the attempt: progress reached, and remaining progress potential.

The first way-point feeds is an indication of how much progress has been made. When compared to progress expectations, we peek into the trailing indicator of value so far emerged.

The second continuous progress judgement is of progress potential. This is how far does the seeker feel they can reach from a point in time. When compared with progress sought (or offered if engaging a proposition) we peek into the leading indicator of future value.

Let’s frame our value model with this type of thinking.

value-through-progress: a view of value creation that primarily focusses on making progress. It sees value as a secondary aspect, emerging as progress is made, and which needs to be recognised by the progress seeker – a process akin to revenue recognition – before it is meaningful to them.

With this in mind, we’re in a position to begin defining value.

defining value – a dynamic collection of progress comparisons

Back in the value-in-use model, we saw value as an increase in a beneficiary’s (or wider service system’s) well-being but acknowledged that well-being was challenging to define. Although we did note that was an improvement on “maximum price a customer is willing to pay” from value-in-exchange.

Shifting our focus to progress offers a more definable concept. We view progress as a state, encompassing functional, non-functional, and contextual elements. We also see progress as being verb/state transition, indicating movement from one state to another. On top, we name specific states to serve as waypoints on these journeys.

We find that seekers judge aspects of progress, often expressing them in terms of value. When they say, “This tool is valuable,” they mean, “This tool (proposition) is most likely to be helpful when I attempt progress from my current origin to my desired state of progress sought.” Or “this tool (proposition) best helped me…” progress (and thus value).

What does this mean for value? Value for a customer is a measure of the ability to, and achievement of, progress to their more desirable state (progress sought)

In practical terms value is a collection of progress comparisons between an actor’s specific judgements of progress and their expectations. These progress judgements, and subsequently comparisons, are uniquely and phenomenologically determined by the actor (as per service-dominant logic). The collection of comparisons varies at different phases of progress and by actor making comparisons (an evolution from service-dominant logic)

value: a dynamic collection of progress comparisons uniquely and phenomenologically made by a participating actor, before, during, and after a progress attempt.

As an example, when looking to start a progress attempt, a progress seeker compares their judgement of potential progress against their expectation of progress sought. The closer the comparison, the greater their perception of value.

It is the subjective, unique, phenomenological, and multi-faceted nature, that brings complexity to understanding value. Yet it is precisely through understanding this complexity we find the systematic levers enabling us to systematically drive growth/innovation.

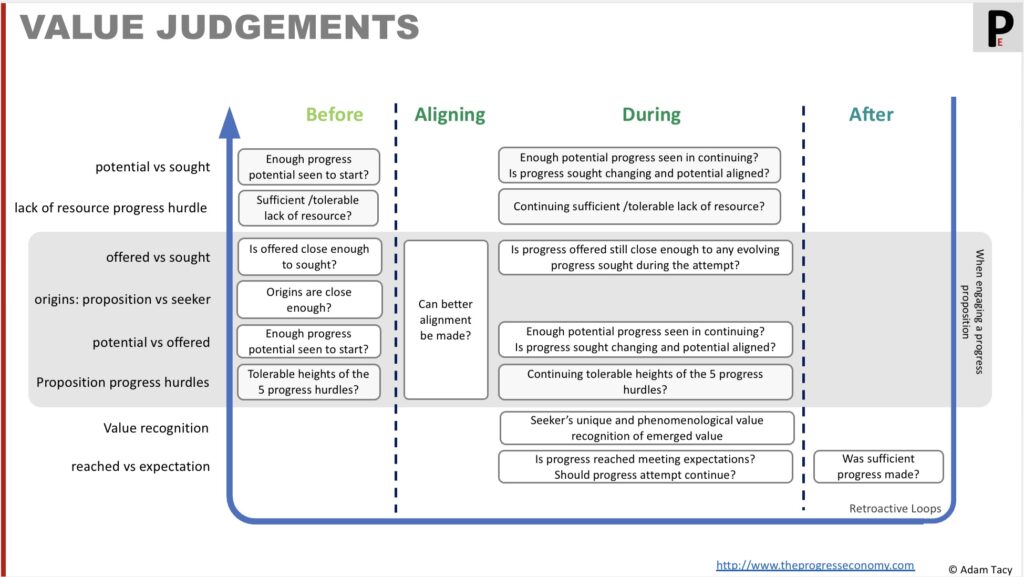

what are these progress comparisons / value judgements?

There are a number of progress comparisons that make up value. They differ through the progress attempt, that’s why we define value as a dynamic collection of comparisons.

We can best visualise the various progress comparisons by grouping them into three stages: before, during, and after a progress attempt. As well as grouping those made when a seeker makes a solo progress attempt and those additional/updated comparisons when engaging a proposition.

Before a progress attempt, actors assess whether they feel sufficient progress could be made. The comparisons are:

- progress potential vs progress sought

- height of lack of resource progress hurdle vs tolerance of lacking resource

- progress offered vs progress sought*

- seeker’s progress origin vs proposition’s origin*

- height of five proposition related progress hurdles vs tolerance of those hurdles*

* when engaging a proposition

During the attempt, actors focus on value recognition, and regularly comparing progress made and remaining progress potential against their expectations. They also continually judge all progress hurdles (propositions introduce five additional hurdles).

- value recognition

- progress reached vs progress expected

- (remaining) progress potential vs progress sought

- height of lack of resource progress hurdle vs tolerance of lacking resource

- (remaining) progress potential vs progress offered*

- height of five proposition related progress hurdles vs tolerance of those hurdles*

* when engaging a proposition

One thing we need to be aware of is that progress sought can evolve during the attempt. Progress offered may also evolve if the helper responsively updates their offering. This is due to experience gained by actors in this and/or other attempts being made (even in other markets/industries).

There is also an alignment sub-phase that may happen prior to progress proper being made. In this period, seeker and helper attempt to reduce seeker’s value judgement gaps and hurdle judgements.

After a progress attempt there is a final judgement of progress reached.

- progress reached vs progress expected

- height of equitable exchange hurdle

- potentially heights of the five other progress hurdles

Finally, what an actor learns during attempts gets feedback to the start of other attempts. And for a seeker that means both attempts for the same aspect of progress sought and other aspects.

Who determines value?

When it comes to who determines value, we hold with the service-dominant logic view that it is the seeker (beneficiary).

value is always uniquely and phenomenologically determined by the beneficiary

#10

We therefore refer to the progress comparisons made by a progress seeker as value judgments. As mentioned earlier, value judgments and progress comparisons are two sides of the same coin.

However, we must recognise the practicality that progress helpers may make their own progress comparisons relating to a specific seeker’s attempt. These include judging progress potential, the likelihood of successful equitable exchange, and the progress reached. The results of such progress comparisons can lead to two actions: helpers may either withdraw their supplementary resources or add additional resource to try to recover from value destruction (hindering of progress).

It’s important to keep in mind that helper-made progress comparisons are independent of, and do not directly influence, a seeker’s value judgments. To avoid confusion, we will continue calling them progress comparisons.

On the next page we’ll look at how value is created, potentially destroyed, and measured.

Let’s progress together through discussion…