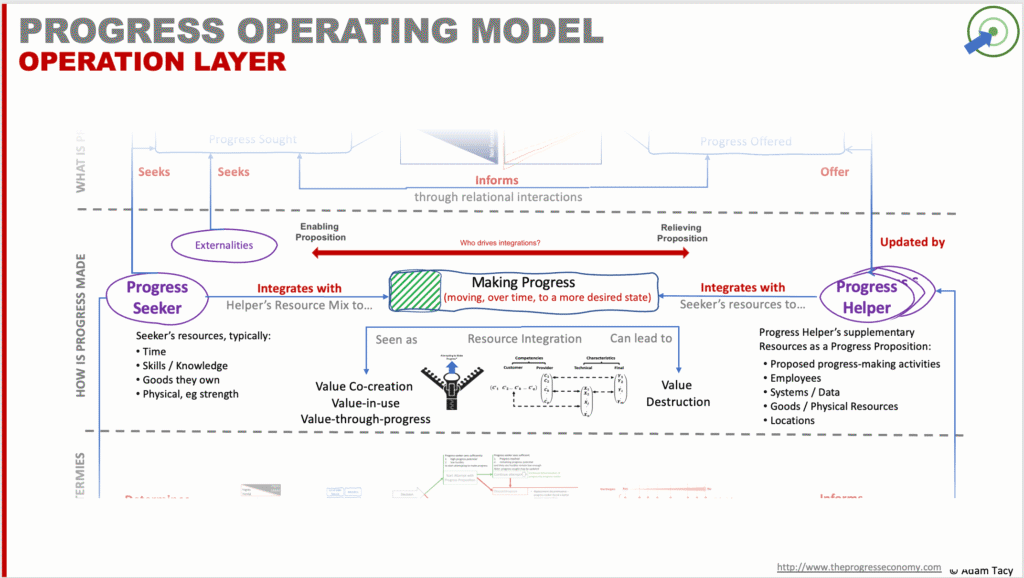

Operational Layer: Making and helping make progress

The operational layer is where progress happens. It is where capabilities are applied, by integrating resources that carry them. Here’s how it looks:

It is in this layer we find the definitions of the progress economy’s three actors.

Meet the actors

We identify three actors in the progress economy – the Seeker and Helper we’ve briefly met before, and Externalities.

We put Helpers on one side of our diagram and Seekers and Externalities on the other. This is because the first deals with progress offered and the later with progress sought.

| actor | description |

|---|---|

| Progress Seeker (Seeker for short) | Individuals or organisations who look to reach a more desired state (progress sought) from where they are now (their progress origin). We are all progress seekers with every aspect of our lives, though we likely do not have all the capabilities necessary to make all the necessary progress (we call this the lack of capability progress hurdle) |

| Progress Helper (often shortened to Helper) | Individuals or organisations offering to help Seekers move to a state of progress offered from an assumed progress origin. They do so by offering progress propositions that provide supplementary capabilities, carried by a specific resource mix. Helpers obtain/develop these capabilities in a variety of ways: trial and error (when attempting progress themselves; or undertaken R&D/innovation activities); transferring from other markets/industries they operate in; being taught by others, etc. |

| Externalities | institutions such as governments, societal norms, or standards bodies that insert progress aspects into Seeker’s progress sought for the common good. |

Externalities insert additional aspects of progress into a Seeker’s progress sought for the benefit of the common good. They might be aspects that the Seeker doesn’t want, or isn’t aware they need. For example, regulations may require that natural gas installations in homes be performed by certified professionals. In this case, government, as an Externality, effectively adds a mandated capability on the Seeker via their progress sought.

While it might initially seem more intuitive to assign this to the Helper’s progress offered, we place it within the Seeker’s progress sought because the Seeker is the primary progress actor. They look to make the progress attempt, and if they are a certified gas engineer, then that’s fine. Likely, though, they find they have capability gap, as they are not a certified gas engineer. That suggests they turn to a Helper who offers certified gas engineers.

We’ll also talk of a Progress Owner. They sit in a Helper, and are responsible for ensuring a Seeker makes the best/most progress. As such, they are responsible for a proposition’s alignment, execution and innovation. They are the next evolution of a product owner.

The mechanics of making progress: Resource Integration

Seekers make progress attempts to try and make their progress journey (remember that whilst this covers everything in their life, for practical analysis reasons, we usually consider one aspect of the journey at a time).

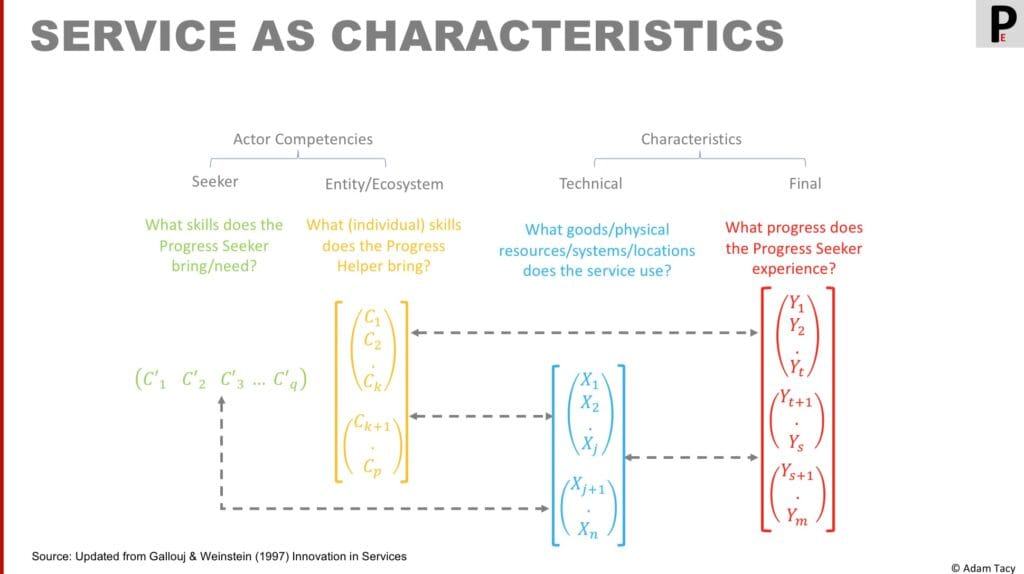

Progress happens by executing progress-making activities – specific activities that integrate two or more resources. These integrations effectively apply capabilities of operant resources (those that act on other resources, such as the Seeker and some types of systems, for example artificial intelligence) on operand resources (those that are acted upon, like goods).

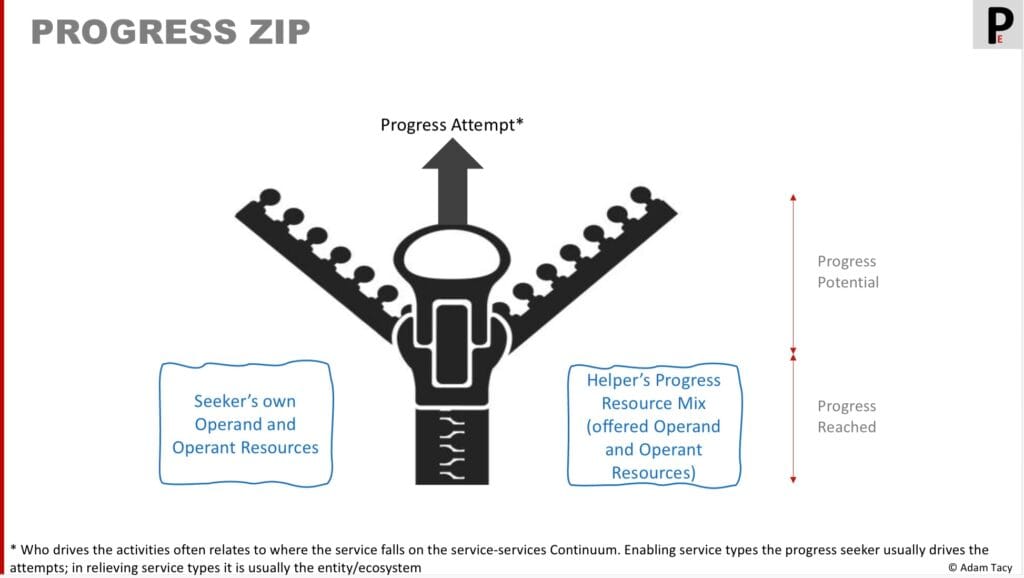

That’s quite a lot to unpack! Imagine it like a zip. The Seeker attempts to pulls the zipper up one notch (a progress-making activity), by integrating resources together. Say they are seeking to join two pieces of material together and they’ve decided to use a screw and a screwdriver. The Seeker here is an operant resource, having the skills and knowledge (capabilities) of how to use a screwdriver. The screwdriver is an operand resource, it can do nothing on its own, but carries the capability to transfer torque applied to it to turn a screw with a specific head.

Each successful twist of the screwdriver by the Seeker moves the Seeker closer to their progress sought.

If we wanted to be complete in this example, then we would see the two pieces of material as two other operand resources; that the screw also contained the capability to join those materials together; and that the Seeker knew how to choose the right type of screw and screwdriver to make successful progress.

The progress making activities are likely be as follows:

- identify correct screw to join the materials together

- select the correct screwdriver for that screw

- drill a pilot hole to guide the screwing

- connect screw to first material

- twist screwdriver enough times to join the two materials together

Understanding these integrations is critical because value only emerges when progress is made…not when a product is bought, not when a service is delivered, but when capabilities are successfully applied, moving the Seeker forward.

As we’ve already touched on, when a Seeker lacks the capabilities needed to move forward, they encounter a lack of capability progress hurdle. This can take many forms. They might not have the right screw or screwdriver. They may not know which type of screw to choose, or even how to use a screwdriver (though with a little common sense, they might figure it out). But more subtle barriers often arise: not knowing that drilling a guide hole improves the outcome or facing a physical limitation that raises the bar on tool design or ease of use. Or simply, they may not have the time to do it themselves.

When Seekers lack a necessary capability to make progress themselves, they may attempt to generate/find it via trial and error. More often, they engage a progress propositions offered by a Progress Helper.

Helping Progress

Progress Helpers offer to help a Seeker make progress by offering supplementary capabilities carried by specific resources. We call this a progress proposition and they are made up of a:

- proposed series of progress-making activities, and

- proposition-specific resource mix that carry the missing capabilities.

But not all propositions are created equal. We saw in the strategic layer there are a lot of strategic choices around progress offered and the propositions progress origin. Here in the operation layer those choices extend to:

- what are the progress-making activities proposed

- how voluntary those activities are

- the composition of their resource mix

Those proposed progress-making activities are also a source for innovation. Can you offer better progress by innovating on them?

Progress is now a joint endeavour between Seeker and Helper. Both contribute capabilities and resources. Together they pull the zip, performing a series of activities, that move the Seeker forward.

Gallouj and Weinstein give us a Service as Characteristics model, which we’ll update and revisit later (since it formalises this dynamic)

The summary is that progress is not delivered; it is made through coordinated action. Who drives those actions (pulls the zip) has interesting implications.

Enabled vs relieved: a continuum of help

Progress propositions fall on a continuum between enabling and relieving, driven by who performs the majority of the progress-making activities:

- enabling propositions equip the Seeker to perform most of the progress-making activities themselves (the screw and the screwdriver).

- relieving propositions take on most of the effort, delivering outcomes with minimal involvement from the Seeker (the handyman).

This positioning has strategic implications.

- Enabling propositions often involve operand resources (e.g. tools) and deliver non-functional progress like “gained mastery” or “not being held up.”; and often have a smaller span of progress journey (meaning Seekers often need to chain several propositions together to make their progress journey)

- Relieving propositions lean on operant resources (e.g. people, AI systems), offer a wider progress journey span. and reduce availability, skill, and cognitive burdens.

Interestingly, each Seeker takes a position on this continuum for each progress attempt they make. The closer the match between Seeker and proposition positioning, the more attractive the proposition, driving higher perceived value. A poor fit raises the continuum misalignment progress hurdle. If the Seeker is looking to be fully relieved but you are offering a fully enabling proposition, or vice-versa, the hurdle is the highest.

This continuum allows for targeted innovation. For example:

- Offering more “relieving” options for time-/skill-/knowledge-poor Seekers,

- Or creating lightweight, modular “enabling” tools for hands-on Seekers.

You might already be thinking the world is shifting to relieving propositions (maybe under the guise of “shifting to a service economy“). It is; but there are also plenty of Seekers looking to be enabled – especially where mastery, control, or privacy matter.

Progress resource mix

As a Helper, you offer supplementary capabilities. They are carried in a specific resource mix for your proposition – the handyman, or the screwdriver & screws. That mix is influenced by where your proposition is placed on the progress continuum (or vice versa, where you want to position influences the resource mix).

We recognise 6 resource types in the progress economy.

| Resource | Description |

|---|---|

| employees | seeker facing employees – these are often the source of strategic benefit. We include AI in this group |

| systems | can be operand () or operant (like a word processor) |

| goods | physical or digital items that freeze service allowing it to be distributed (service is unfrozen at point and time of need by an act of resource integration) |

| physical resources | goods where ownership is not transferred |

| data | a wide range of information |

| locations | physical or digital places where service is carried out |

The resource mix is a prime source for innovation. Resources can be swapped for others, as long as the capabilities offered (and needed by the Seeker) are the same or better.

Some quick example of altering the mix are:

- shifting from offering goods to offering a service – a Helper offering a handyman for screwing together the two materials above. The progress made is the same, the capabilities are the same, the resources the Seeker engages are different: an employee rather than a set of goods

- “servitisation” where goods are being wrapped as services, offering better progress than just goods itself – Rolls Royce “power by the hour” on their aircraft engines, for example

- home brew beer – offering the materials and tools needed to brew your own beer rather than drinking commercial offerings

Proposed progress-making activities

The proposed progress-making activities are another prime area for innovation. You’d likely call this process innovation – can you improve or reduce the activities? Leveraging the progress continuum insights, we can also ponder if progress can be improved by shifting who performs the activities.

And these activities are a way for a Helper to “capture value”, to borrow a traditional world phrase. Those activities that the Helper performs can be hidden from the Seeker, protecting them from being copied by other Helpers. They can also be the driver of how you offer better progress, and so attract more/higher exchanges. That said, offering proposed progress-making activities the Seeker performs can also lead to more/hgher exchanges if they better align with Seekers’ progress sought (often non-functional: simpler, quicker, more customisable, less customisable…)

Value emerges from progress

Importantly, we have a shift in how we see value. We no longer see manufacturers embedding value, exchanging it at a point of sale and a customer then destroying, or using it up. That value-in-exchage model, whilst having been wildly successful to date, has many blindspots that are now impacting our growth.

As Grönroos says:

It is of course only logical to assume that the value really emerges for customers when goods and services do something for them. Before this happens, only potential value exists

Grönroos (2004) “Adopting a service logic for marketing”

In the progress economy, we see value as a set of progress comparisons.

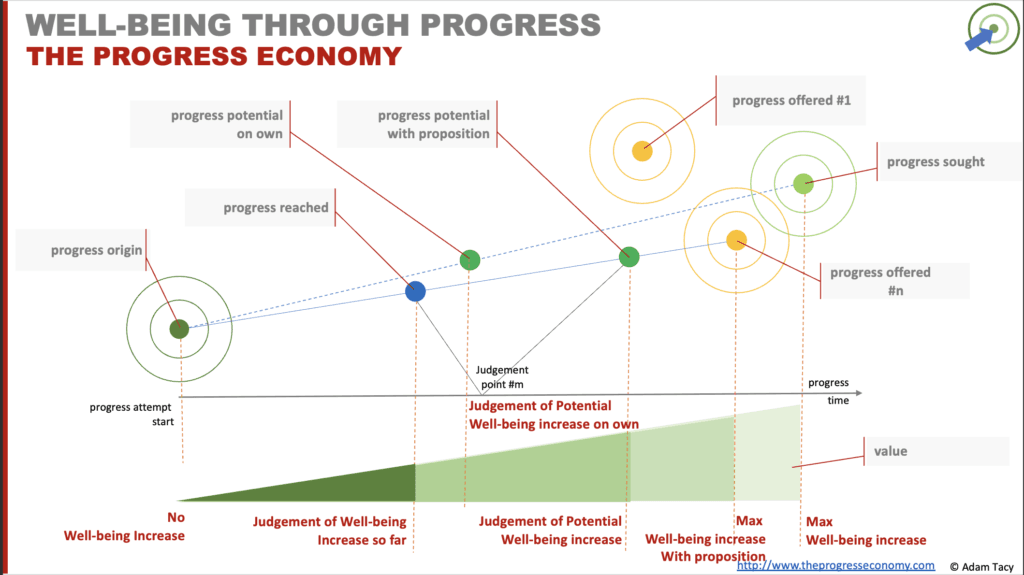

There is potential value, which effectively compares a Seeker’s judgement of progress they feel they could make to their progress sought. And there is emerged value – how much progress does a Seeker judge they have made towards their progress sought.

Value emerges as the Seeker progresses from their origin to their more desired state of progress sought. At the origin, there is no emerged value, since progress reached is furthest from progress sought; however, there is potential – the Seeker’s comparison of how close to their progress sought they can reach.

As progress is made, potential is realised as emerged value – what we call value-through-progress. We conceptualise this as linear emergence. And value peaks when the Seeker reaches their desired state. There progress reached equals progress sought. When engaging a proposition a Seeker additionally judges how close progress offered is to their progress sought, as well as how close the proposition’s origin is to their own.

But, as value emerges, it may not be immediately meaningful to them. It needs to be recognised – similar to how revenue is recognised in a firm. We’ll come back to this in the decision layer.

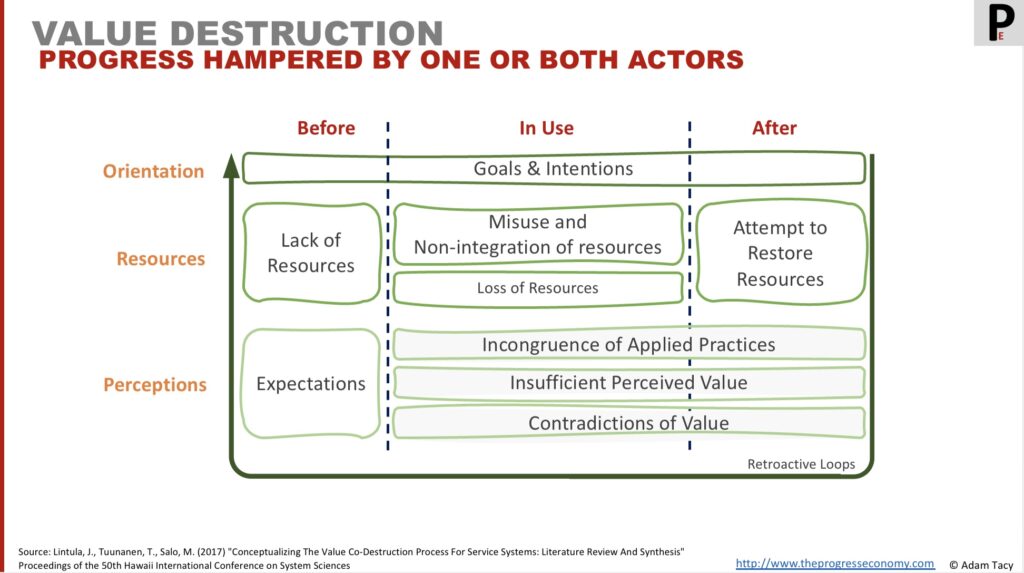

As well as emerging, value may be destroyed.

Value Destruction

Not all attempts at progress succeed. For example, when resources are poorly integrated or capabilities misapplied, the Seeker may experience frustration, and failure. In short, this is value destruction (and is a very different concept to value destruction in our traditional value model).

Lintel et al identified where and why value destruction can occur (although they call it value co-destruction, to mirror most service logics concept of value co-creation – we don’t have that, we just have progress…).

In the progress economy, value destruction is where making progress is hampered beyond the action of the progress hurdles.

Understanding these breakdown points is just as important as tracking success. They reveal innovation opportunities, design flaws, and unmet capability needs.

Avoiding, or minimising, value destruction points to a dialogue/relational basis underpinning progress. As ever, identifying progress problems as early as possible leads to manageable impacts, and reduces need of Seeker to “attempt to restore resources” – which is them, for example, going on social media and attacking your service. This is a topic we’ll come back to in the decision layer.

Service Credits

A more challenging aspect of the progress economy is that economic activity is based on service exchange. As Service-Dominant Logic – one of our foundations – reminds us, we don’t exchange value, we exchange service: the application of capabilities for benefit.

Service is the fundamental basis of exchange

#1

This also naturally falls out from the three key principles we saw in the introduction, but is very different to how we learn, and observe, the world works in a goods-dominant / value-in-exchange world (the basis of many economics and MBA courses). And we have a “problem” – since we shift from a value-in-exchange world view, what does price mean?

Luckily, service credits are the answer, and their relevance is to how we see price, business models and another progress hurdle: inequitable exchange. Let’s build up why.

Say I help you move house. There’s a reasonable expectation that you’ll help me with something in return. Maybe you help me move at some other point, or you offer to cook me a nice meal, or you buy me some gift. This is a nice simple bi-directional service exchange – and we probably keep tack of it in our heads.

Once we start looking a bit wider though, we would have more of these types of arrangements with more parties, and the return service is often at some later point in time. We might want a more formal way to keep track of them. Perhaps a simple note of who I owe a service to, and who owes me a service – a service credit. And you might write those down in a book, or a centralised “ledger” available to everyone, or distributed as some form of tokens.

Then if we take a next step up, we might think that not all service is of equal effort. Helping you move house might have taken all weekend; does one home cooked meal feel fair? Maybe helping to move should have 4 service credits. So now service credits start reflecting effort provided in a service.

We also know that in our more complex worldm we rarely have such direct exchanges between two parties. In fact, service-dominant logic tells us:

indirect exchange masks the fundamental basis of exchange

#2

Service tokens lubricate these indirect exchanges. For example, I apply my capabilities for my employers benefit, but I don’t need a service from them. Instead, I accept service credits for my effort. I can then use those service credits with another party to get their service, without me providing a service to them. This is an example of transitive indirect service exchange; there are others.

From this we see why price is an indicator of service effort expected in exchange for executing a service.

To tie it together: money is a highly successful implementation of service credits. But others have existed_ rocks, local credit coins, blockchain-based coins. Regardless of form, they solve for timing, scaling, and transitivity in service exchange.

Understanding this, and the effort of service being exchanged, unlocks business model innovation: subscription, tokenisation, loyalty, freemium.

Implications for Helpers

The more complex or emotional the journey, the more influence a Helper can exert by maintaining interaction throughout. Continuous dialogue allows Helpers to:

- Reinforce positive judgments,

- Reduce hurdle perceptions,

- Enable or relieve according to preference,

- Encourage early value recognition,

- And prevent discontinuance.

In contrast, goods-dominant propositions (like tools or consumables) may have fewer built-in feedback loops. To address this, some Helpers establish online forums, FAQs, or customer communities to simulate dialogue and maintain presence.

Even when the Seeker doesn’t speak to the Helper directly, they will speak – often through online reviews or social channels. In the Progress Economy, those conversations are part of the value system.

Let’s progress together through discussion…