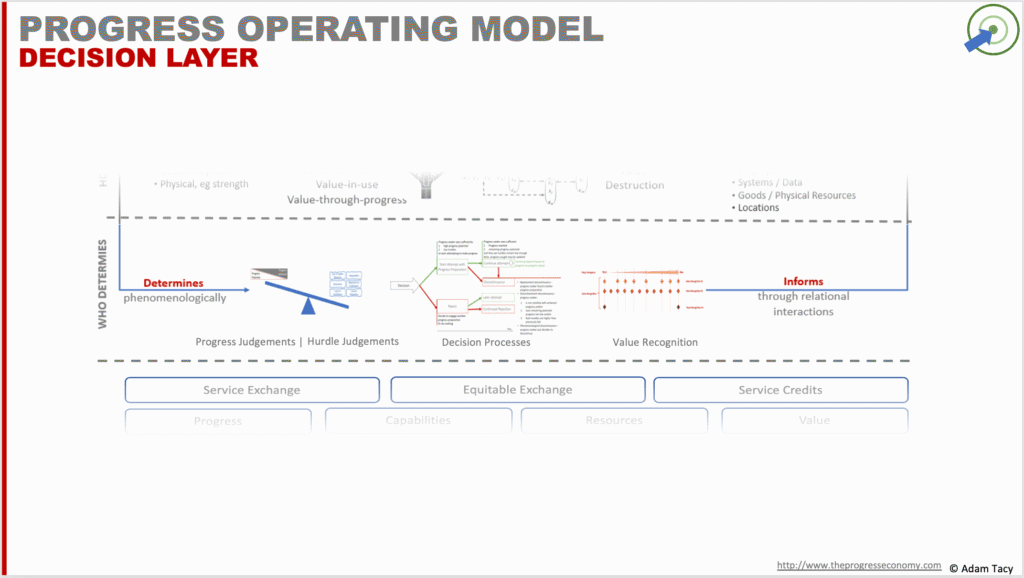

Decision Layer: phenomenological decisions that shape progress

Progress is not just made – it is judged, rejudged, and sometimes abandoned. Seekers continuously evaluate their journey: Can I make progress? Am I making enough? Are the hurdles worth it? Does the progress feel real or meaningful? These are phenomenological decisions, and they form the decision layer of the Progress Economy.

These judgments are inherently subjective. They are shaped by the Seeker’s personal history, current emotions, and situational context. They are, phenomenological. It’s the reason someone might embrace a self-checkout kiosk when grabbing a sandwich on a rainy, rushed Tuesday—yet avoid it entirely when doing the weekly family shop. Another person might always prefer it; another might never trust it. These preferences are not just quirks—they’re strategic signals.

Helpers should try and objectify these judgements where there is not a natural measurement. For example, learning languages is often against a framework allowing a student to more objectively measure their progress.

Dialogue and interaction matter – but not always

While Seekers constantly make these micro-decisions, not all progress attempts are created equal. Some are short and transactional, requiring little interaction or reflection. Others unfold over time, demand investment, and involve complex tradeoffs. The implication for Helpers is clear: the longer and more complex the journey, the more opportunity (and necessity) for dialogue and interaction.

A helpful proposition doesn’t just provide capability it actively guides the Seeker’s decision-making through contextual feedback, timely interventions, and trust-building moments.

Judgements of progress

At the heart of the decision layer are two fundamental judgments:

- Progress potential – how much progress the Seeker believes they can make.

- Progress achieved – how much progress they believe they have made so far.

Effective propositions work to elevate both. When Seekers feel confident about where they can go—and feel that they are indeed moving toward it—they stay engaged.

Importantly, these judgments are predominantly made by the Seeker. However, a Helper may make additional judgements in some propositions. A luxury car dealer, for instance, might refuse to proceed with a sale if the buyer’s financial standing seems insufficient. In these cases, the Helper might withhold or withdraw access to their resources (and therefore capabilities).

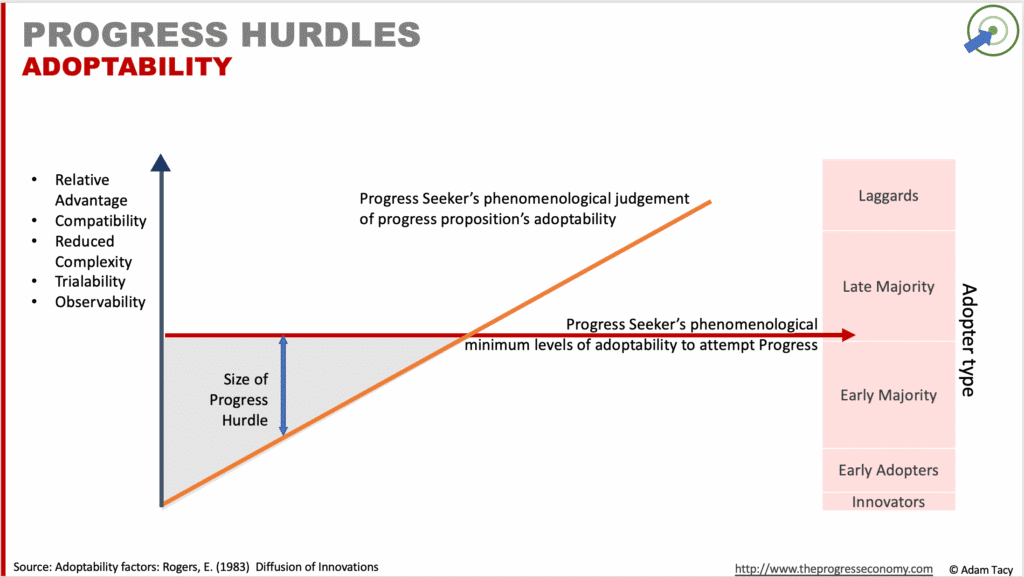

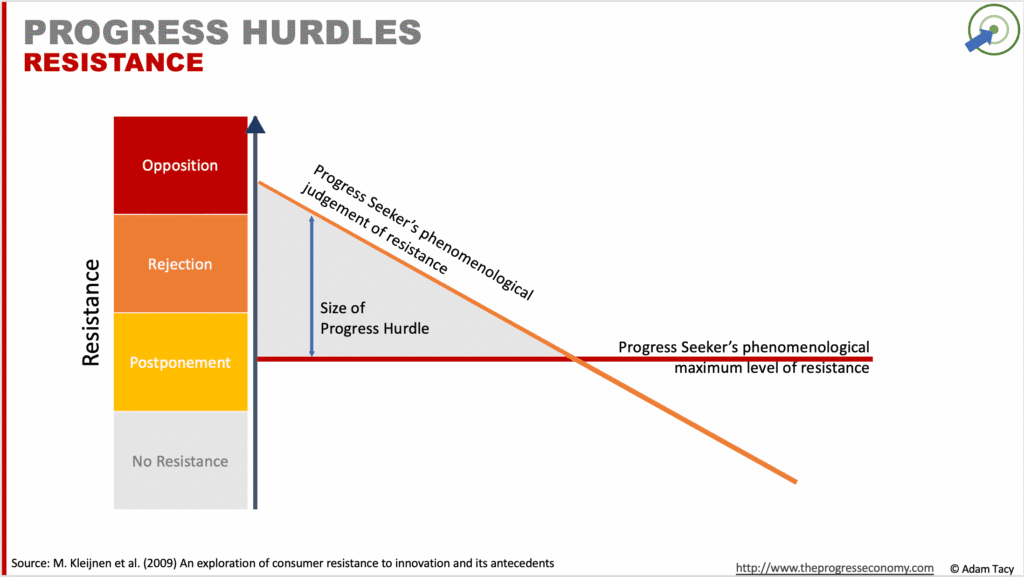

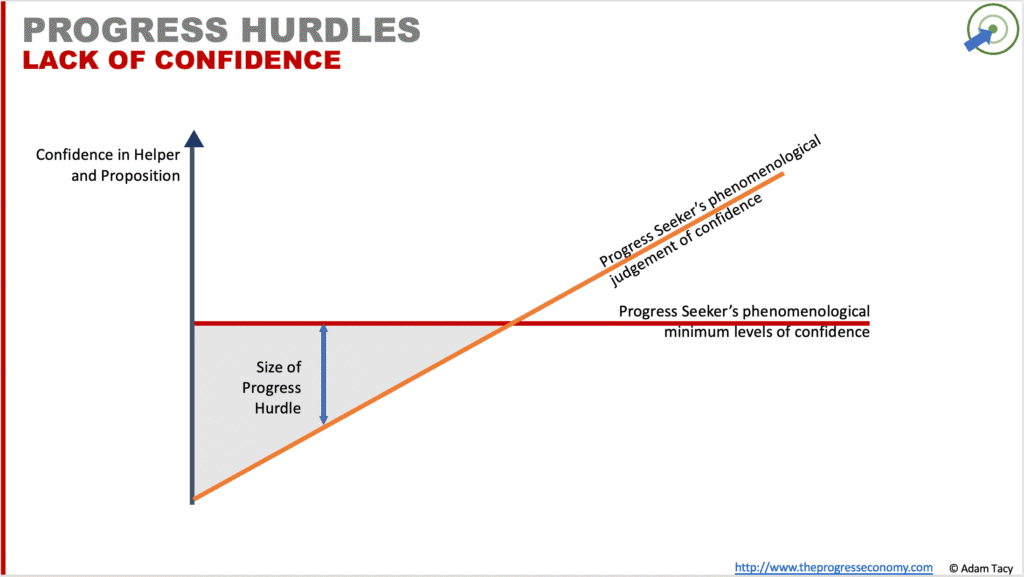

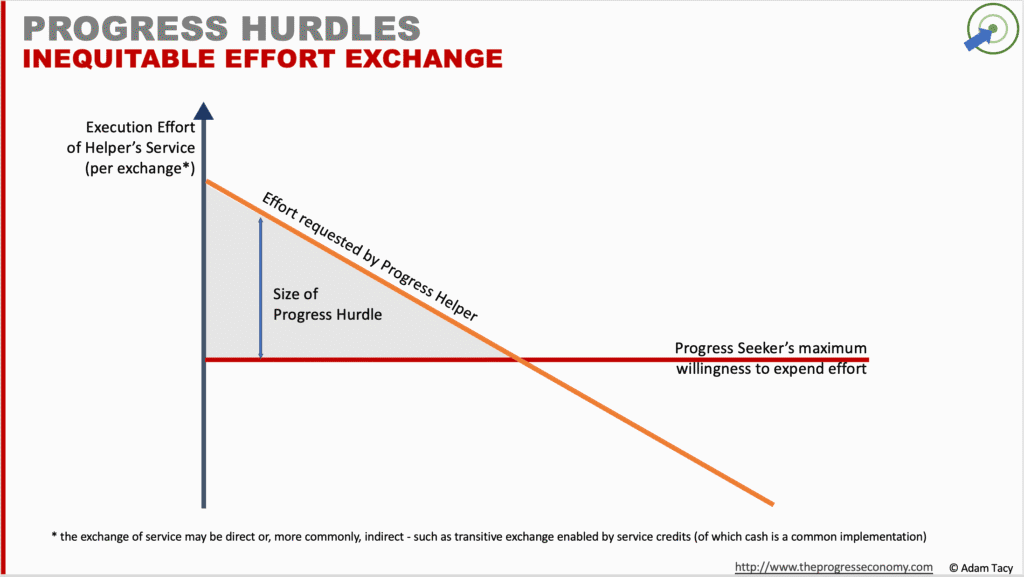

Judgements of progress hurdles

Seekers also judge the height of the six progress hurdles. These are the frictions that stand between them and their progress sought. And perceptions evolve over time. When a hurdle appears too high, the Seeker may choose not to begin, or to discontinue, progress. These hurdles look as follows.

Each Seeker has their own maximum tolerable hurdle heights. It may be a matter of lacking time (availability), capability (skills or knowledge), or confidence (emotional resistance). Even with help, some hurdles may still feel insurmountable.

The story of Google Glass illustrates this well regarding the resistance hurdle. The product felt intrusive and socially uncomfortable by the majority of the public (despite being loved by some techies). Who wanted to be talking to someone who could be invisibly recording you and searching info on you! By contrast, Snapchat Spectacles repackaged the idea into something playful and transparent, better matching user expectations. Later, Google Glass found renewed relevance in industrial settings, where different progress criteria applied. The technology didn’t change much, but the context and hurdle judgments did.

The key takeaway: perception trumps design. Helpers must understand the hurdle profile of their Seekers and tailor propositions to lower, circumvent, or reframe those hurdles.

Of course, these are hurdles, not barriers, so even if the judgements fall below the Seeker’s preferences, they might still attempt progress – you lovely, complex, human being!

Value: comparisons of progress

In the Progress Economy, value doesn’t reside in the product or the exchange. It emerges from progress. More specifically, value is a set of progress comparisons that the Seeker makes:

- Emerged Value is a comparison between:

- The progress the Seeker has made

- What they expected to make at that point

- The total progress they hope to achieve (progress sought or progress offered)

- Potential Value is a forward-looking judgment:

- How close the Seeker believes they can get to their desired state

- How closely the proposition’s progress offered matches their progress sought

- How far the proposition’s origin is from the Seeker’s current state

These comparisons form the basis of perceived value. Helpers who understand and influence these judgments will consistently outperform those who focus only on feature sets or price points.

Recognising value

Emerged value isn’t enough, it must also be recognised by the Seeker to be meaningful.

Imagine a Seeker needs to travel 100km. On Day 1, they travel 80km. If they believe they can complete the remaining 20km tomorrow, that 80km has clear meaning: progress has emerged and is recognised. But if the entire journey had to be completed on Day 1, and they fall short, those 80km may feel as meaningless as 0km.

Recognition is subjective, temporal, and highly contextual. Helpers should design for early recognition, helping Seekers see and feel their progress, fast. Whether through data visualisation, feedback loops, emotional markers, or progress milestones, early, and more frequent, recognition drives motivation, trust, and momentum.

Progress decision process

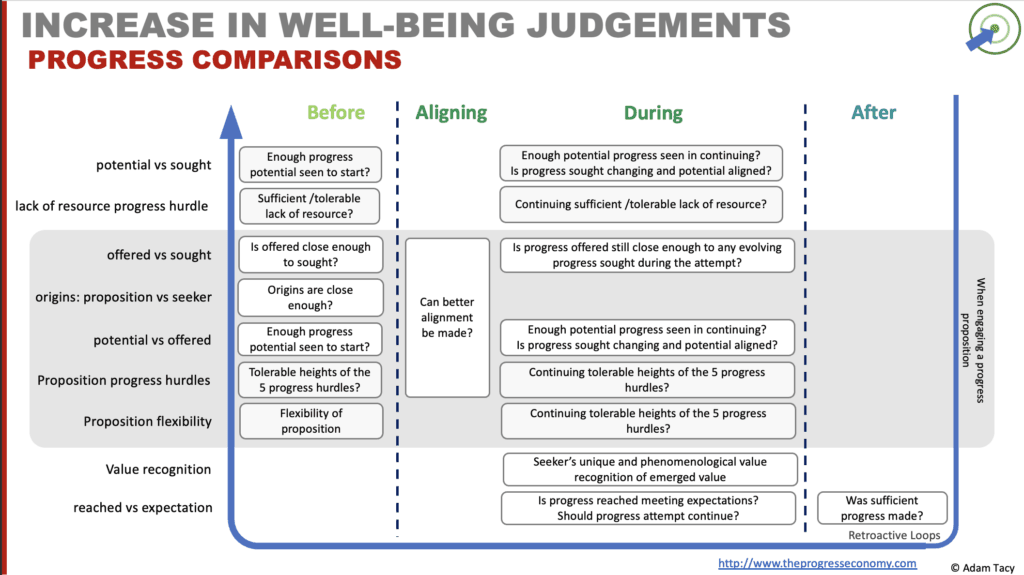

All this ultimately helps us understand that Seeker’s have a defined decision process they follow during a progress attempt (and when engaging a proposition, it is a similar process, just with slightly altered decisions). We can visualise this in the following diagram.

Seekers make an initial decision to attempt progress or not by judging their progress potential and the height of the six progress hurdles. If they are favourable, they will initiate progress. Whilst progressing they will repeatedly judge have they got far enough, and if they still think they can keep going. If they don’t then there is a discontinuance – either they’ve found a more attractive way to progress, they’re disillusioned with this attempt, or they just decide they don’t want to continue.

Given this process, it can be seen that Helpers who have dialogues and interactions have a greater opportunity to influence the decisions and minimise abandonment.

However, the shorter the attempt, the less important the continuous decisions appear to be. For example, there are not many in process follow-ups when a Seeker uses a screw. And the more goods-based a Helper’s resource-mix is, the less natural opportunities for interaction arise. Some Helpers may address these by having online help forums. Some Seekers may address their perceived value destruction through raising their feelings on online forums (Helper-based or wider).

Let’s progress together through discussion…