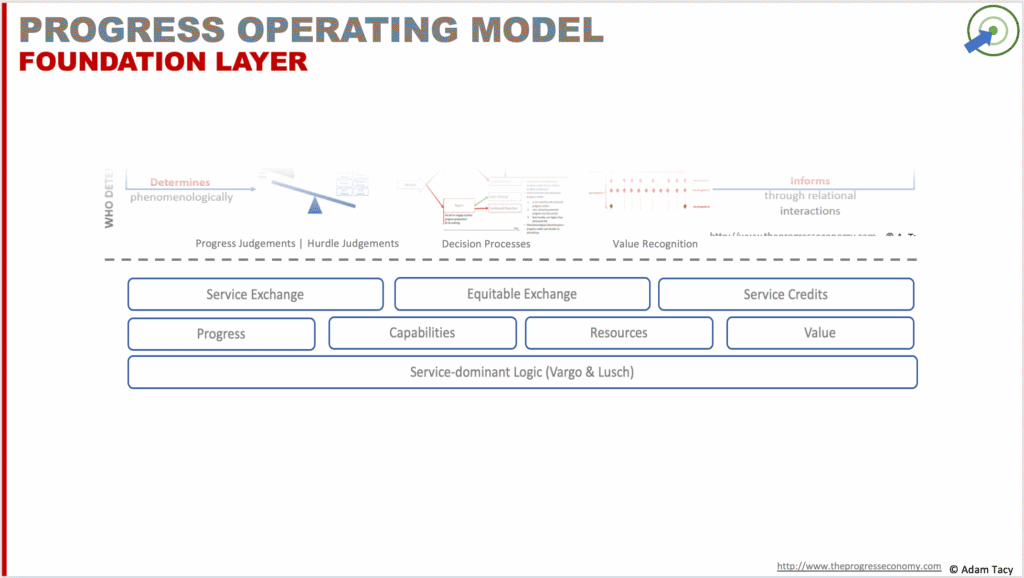

Foundation Layer: the basics

We now arrive at the foundations upon which the progress economy is built. Central to this is the influence of Vargo and Lusch’s service-dominant logic (SDL), which not only informs our view of value but also surfaces progress as the underlying dynamic of all economic activity. From this perspective, progress is driven by the application of capabilities, and those capabilities reside within resources—whether people, systems, data, locations, or goods.

Bringing the “economy” into the progress economy requires a departure from the conventional idea of value as the basis of exchange. Drawing from SDL, we recognise that service—not value—is the true foundation of economic exchange. However, this is often obscured by the complexity of indirect exchange.

Service, by definition, takes effort. And when service is exchanged, we inherently seek equity of effort. This requires mediation, and is provided by what we call service credits. Money, as we’ll see, is simply a successful implementation of service credits. But first, a brief exploration of what this really means.

Service-dominant logic

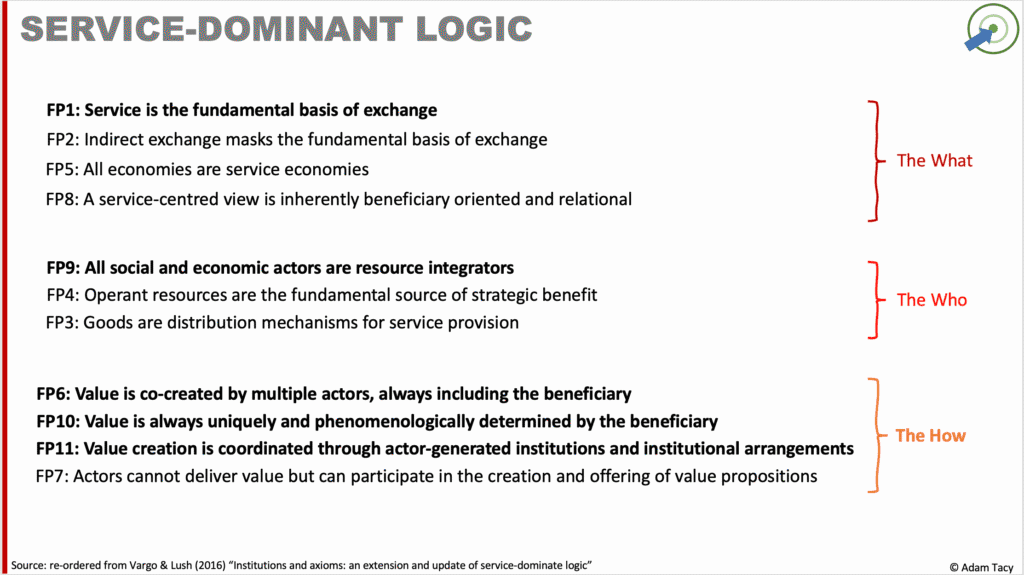

Vargo and Lusch’s service-dominant logic (SDL) reframes value creation away from the traditional value-in-exchange model (rooted in manufacturing and goods) toward value-in-use or value-in-context. This evolution resolves several blind spots that limit innovation and growth found in the traditional model.

SDL introduces several key shifts:

- Service (singular) is defined as the application of competences (skills and knowledge) for the benefit of others. This is about doing, not delivering services.

- Goods are viewed as distribution mechanisms for service. Service is “frozen” into goods, distributed, and then “unfrozen” in acts of resource integration.

- Value is uniquely and phenomenologically determined by the beneficiary based on their prior and current experience (phenomenological). The manufacturer doesn’t embed value and exchange for cash.

After multiple refinements, Vargo and Lusch distilled SDL into 11 foundational premises (five of which are axioms). We group and order them slightly differently for clarity and relevance to the progress economy.

And it is from these, with a couple of alterations, we build-out the progress economy.

Importantly, we adapt FP10 to reflect that while Seekers predominantly judge value, there are contexts in which Helpers additionally make value judgments. This particularly applies when they determine whether helping a Seeker is a justifiable use of their own resources.

We also substitute “value” with “progress” in FP6, FP10, and FP11, aligning with our view that value is a comparison of progress (see Decision Layer).

Finally, we expand the definition of service (singular) to be slightly wider – Vargo & Lusch’s competences (skills and knowledge) are a subset of capabilities; and applying them could be to oneself as well as others (self-service):

service (singular): the application of capabilities for the benefit of oneself or others

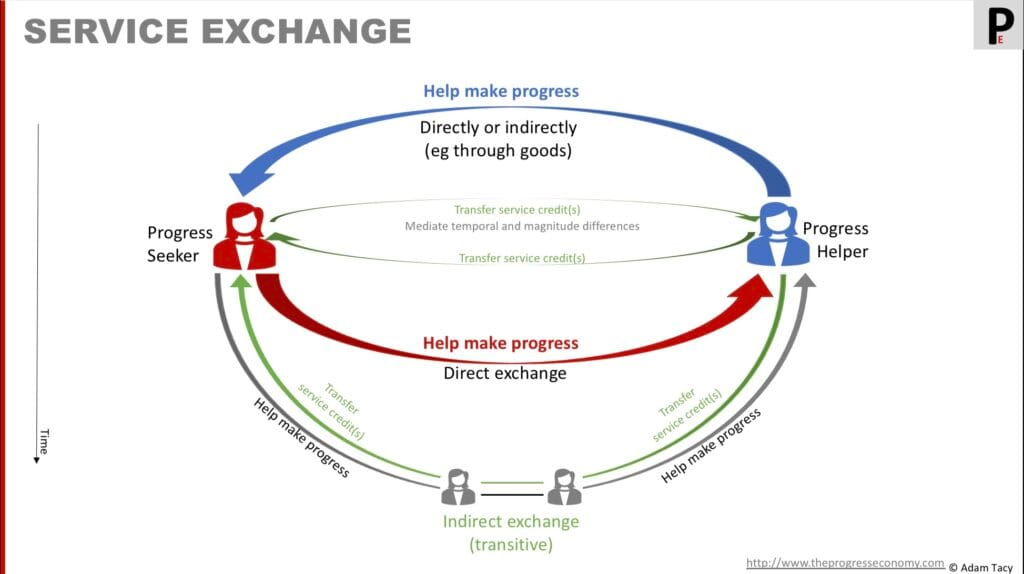

Service exchange: equitable and enabled by service credits

As SDL makes clear, service is the basis of exchange. To appreciate this, recall that service here refers to the application of capabilities for the benefit of oneself or others.

Direct service exchanges occur in our world, but make no mistake, this is no barter economy.

Such exchanges may not be immediate. For instance, I may help you move house, and months later, you might cook me dinner. Mentally, we often track this as “you owe me,” creating an implicit form of accounting – a service ledger of sorts. When scaled across many relationships, this logic pushes toward a need for more formalised mechanisms: we’ll call these service credits. Accounting for them may be centralised or distributed.

Now consider that not all services are of equal magnitude. Helping someone move likely requires more effort than a home-cooked meal. However, we might decide they are equitable, ie we are both happy with efforts applied after one move and one meal. We’ve decided we have an equitable exchange.

Alternatively, we might decide that a move is worth four meals. In this case, I could “earn” four service credits helping you move to redeem for four meals at later times. Outside of our informal relationships, Helper’s effort is often signalled by price – effort expected in return multiplied the number of returns expected. Opening the door to business model innovation.

SDL also informs us that indirect exchange often masks the nature of exchange, We see that with, for example, transitive indirect exchange: I help you, but I want someone else’s help in return, not yours. Service credits lubricate this. I help you, receive service credits, I redeem those with someone else entirely.

Money has been a successful implementation of service credits. Others include rocks, local tokens, and potentially cryptocurrencies like bitcoin.

As you can imagine, money has been a successful implementation of service credits; so have rocks in the post, and perhaps bitcoin is now (at least to some people).

Three Takeaways:

- Service is what’s exchanged

- Effort in those service must feel equitable and “affordable”

- Service credits enable and mediate exchanges, particularly the indirect exchanges that dominate modern economies.

- These concepts tie back in notions of price, money that we lose when evolving from value-in-exchange value model; they also open the door to business model innovation

Progress and Value

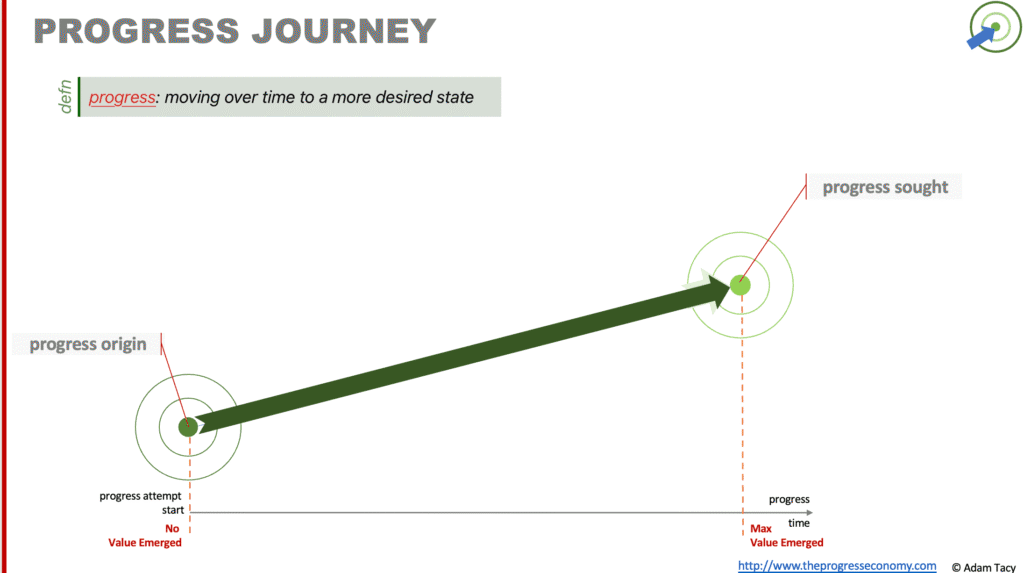

At the heart of the progress economy lies a simple idea:

progress – moving over time to a more desired state

We explore this through five perspectives:

- Progress as a state – comprising three equally important dimensions of functional, non-functional, and contextual.

- Progress as a noun – encompassing three key waypoints (progress origin, progress sought, progress offered) and two judgement points (progress potential, progress reached).

- Progress as a verb – the actual journey a Seeker undertakes from origin to sought (or offered) progress.

- Progress as a measurement – allowing us to track how far the Seeker has advanced.

- Progress as a state transition – another useful lens for describing change over time.

The visual model of progress helps illustrate how value emerges from progress. At the progress origin, there is no value—only potential. As a Seeker moves closer to their progress sought, value emerges.

We’ll use the progress diagram to discuss progress – the simplest form of which is below.

From here we can also see that value emerges from progress. In fact, it is a set of progress comparisons. Simplistically, there is no emerged value at the progress origin, only progress potential. Whereas maximum value has emerged for the Seeker when they reach their progress sought.

This fundamentally shifts the role of business. Instead of focusing on “creating,” “adding,” or “delivering” value, the goal becomes identifying how to help them make better progress, or progress better.

Capabilities and resources

Capabilities are the real enablers of progress. These include skills, knowledge, physical attributes (e.g. strength), natural forces (e.g. wind), or more abstract assets like availability.

These capabilities must be carried by resources—people, systems, goods (physical or digital), natural forces, or even abstract constructs like time. Progress occurs when resources are integrated, meaning capabilities from one resource are applied to those in another.

Resources that actively apply their capabilities to others are referred to as operant resources. These operant resources are typically the source of strategic advantage in the progress economy.

Let’s progress together through discussion…