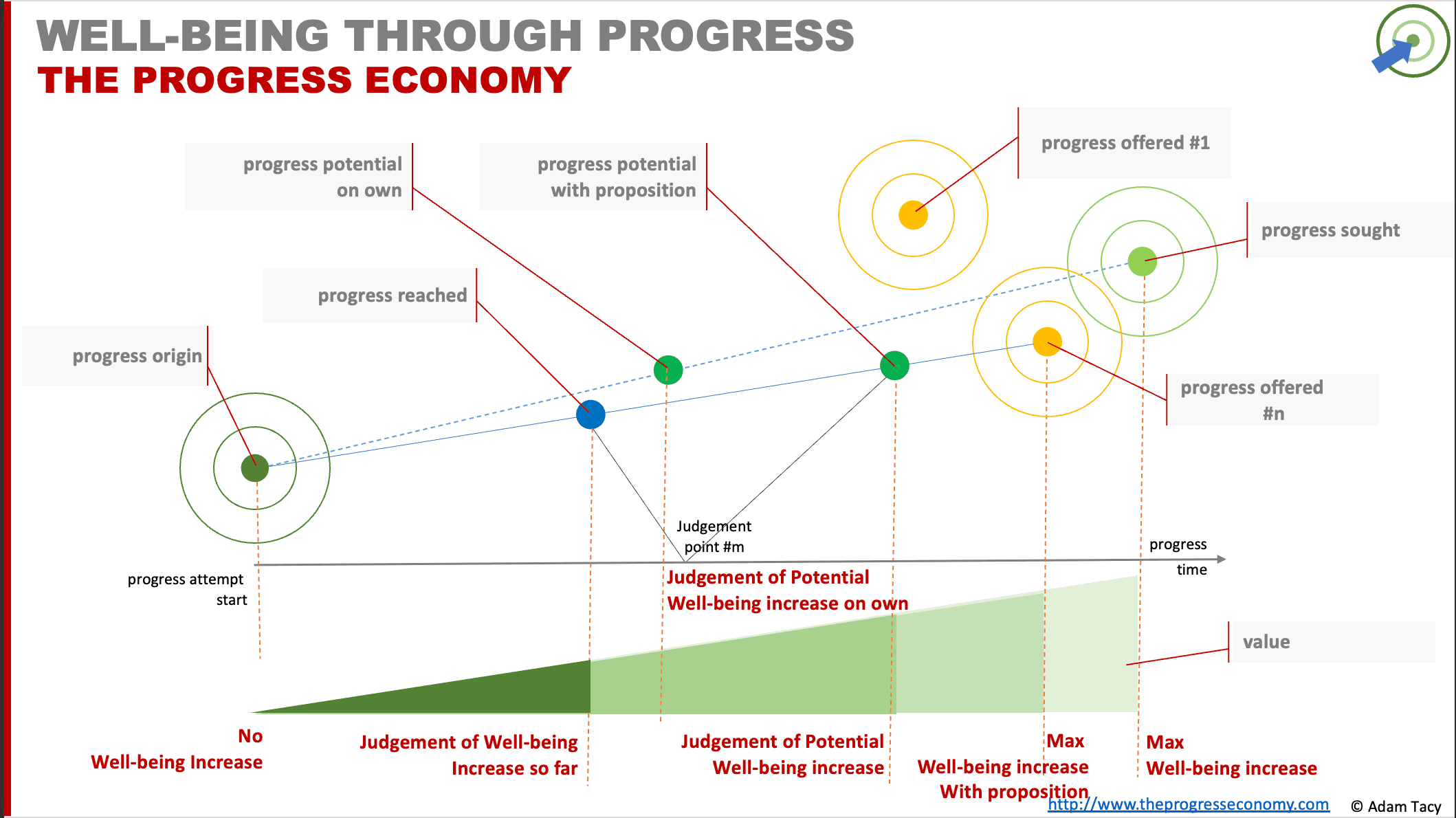

Now we’ll look at how value is created, recognised, potentially destroyed and measured.

During this discussion I’ll use the slightly formal notation introduced in the side bar below. But don’t worry if maths makes you uncomfortable. Behind the notation is really just the concept of taking the difference between two states.

For example, when choosing a proposition to engage with, in the before phase, one of the progress comparisons a seeker makes is to compare the proposition’s progress offered with their own progress sought. I’ll write that, in short form, as:

some notation – the language of value

I’d like to quickly introduce and explain the exciting “formula” we’ll use for value. We’ll take a mathematical approach for clarity, though this is maths in a loose form. If you’re a mathematician, forgive my abuse of notation; I just want a way to describe the English text more formally!

- To start, we’ll represent a progress state as a column vector, denoted by wrapping its three component elements in square brackets. We’ll put the name of the state as a subscript, and the time of judgement as a superscript. Just like you see in the diagram here.

2. Since progress is a move over time, we should understand what time means for us. We’ll refer to several time points:

– somewhere in the “before” phase

– the start of engagement

– after any alignment phase

– when a progress seeker reaches their progress sought/progress offered

– some time after reaching progress sought/offered.

3. Intuitively a comparison of two progress states is the difference between them; something we can represent as a simple subtraction. So, the comparison of with

at time

would look like:

Now we hit two little snags. First, a lot of progress is subjective and non-numerical. But let’s make a little conceit for simplicity and for now pretend they are numerical. Further let’s believe they live on a scale between 0 and 1.

Our second snag is that shorter distances between states, ie better comparisons, result in smaller values. We’d rather like higher results to represent more value. That’s something we can fix by subtracting our comparison result from the maximum number of our scale, which is 1 in our thinking here. This means o difference of becomes

when we invert it.

However, it looks a little messy writing . Instead we’ll show this as a negative power

(meaning

rather than the usual

).

All this means that we’ll write progress comparisons in the following way:

Which has the meaning of at time

is the inverse of the distance between

and

at time t.

Negative values imply that is to the right of

at time

. Whether that means it is better, depends on the comparison.

4. As a last thought, we could imagine applying a dot multiplication function, , that turns the value vector into a single value. Perhaps it applies some strategy involving the weighting of elements, etc.

For those not so familiar with it essentially sums up the multiplication of each row, i.e.:

I’m not sure that gives any additional benefit. When it comes to comparing value judgements, seekers likely have their own phenomenological view of how important, say, functional value is over non-functional value. That is likely too hard to get insight into for all individual seekers once we step away from totally customised service.

5. We’ll use a similar notation for comparisons of progress hurdle heights, where .

With the intended meaning that the barrier height, at any time is the individual seeker’s tolerance minus their judgement of the hurdle height. Positive results imply below the hurdle whereas the larger the negative, the larger the hurdle.

We could collapse this into a single value by applying a dot product with weights:

Doing so may, or may not, be helpful. It depends on whether you can get deep enough insights into how an individual seeker weights each hurdle.

6. When we want to refer to just one hurdle we’ll use a shortcut notation:

7. Finally we’ll use the floor operator () when talking about recognising emerged value.

Now, as I mentioned at the start, this is really just a useful notation to be a little more precise than writing everything in English. It’s not necessarily intended to be calculable. Though you could if so wished; assuming you handle i) progress elements and hurdle heights as numerable items rather than their subjective nature, ii) situations where comparisons return negative values, and iii) perhaps sone other situations.

I’m using it as it’s more precise way of defining, but it will come with descriptive text. You don’t have to be a maths expert to follow, I’ll explain as we go!

Let’s jump in with how see value being created.

creating value / making progress

In our thinking, value is not so much created, it emerges from progress being made (through progress-making activities, which are resource integrations). So we can say that progress should increase over time during an attempt. That is, progress by any time t+1 in the attempt should be greater than the progress at time t. We’ll express this as .

Since value emerges from progress, it follows that the value emerged by any time t+1 in the attempt should be greater than the value that has previously emerged, i.e., at time t. We’ll express this as , or in longer form as:

It’s important to think of the longer form because progress might be made in various combinations of the aspects at different times. One moment might see some functional progress only, another only some non-functional progress; others a combination.

Don’t forget that each aspect may itself be made of several components (progress can be complicated).

To simplify things, we make the convention that contextual progress doesn’t get changed by a progress attempt. If a seeker is looking to change context, say from has no driving license to has a driving license, we treat that as a separate progress attempt with the functional progress sought of gain a driving license.

There is a temptation to collapse the value vector to a single number. After all, we’re humans and a single number is easier than a vector. Theoretically this is possible by applying the dot product function with the second argument being a vector of weights:

Though it requires whoever wants to do this to have good insights into the weightings a seeker would apply (which are unique and phenomenological, though generalisations may be observed).

Whether collapsing value vector to a single number is useful or not is an ongoing debate. Understanding those weights, however, is something a helper should do when crafting a proposition. To know what progress is most important to seeker(s).

Perhaps they use them when leveraging the progress economy’s interpretation of Blue Ocean Strategy’s strategy canvas). Both to identify Blue Oceans or more simply progress components that seekers struggle with that are not currently well addressed. Or perhaps to identify key progress components they will focus on in interactions during progress attempts.

As I’ve mentioned, value is a progress comparisons between expected and actual progress states. This is what we see here, where , at any time t, compares progress reached,

, with expectation of progressed reached

by that time t. Written as:

This is the trailing metric that I previously mentioned. It is trailing as it indicates progress made. We’ll just refer to this as emerged value on a solo attempt. However, when engaging a progress proposition, progress is now a joint endeavour. Whilst this is still emerged value, the literature likes to talk of value co-creation. Either phrase works – co-emerged value doesn’t make any sense.

If value is not increasing over time then it is because progress is not being made. Sometimes that’s just because the seeker is taking a pause. There is, though, a more worrisome reason; we might be observing value destruction.

destroying value / hindering progress

Progress may not be happening in an attempt for a variety of reasons. As mentioned above, it may just innocently be because the seeker is taking a pause for reasons known to them. It may also be due to one or more involved actors causing it to stall. We call this later case value destruction.

value destruction – when one or more actors involved in a progress attempt hinder progress being made

This is the same concept we saw in value-in-use model. Although I frame it in terms of hindering progress rather than a reduction in well-being. A little more formally, value destruction may be occurring if value emerging by any time t+1, , being less than or equal to that at time t,

:

In the same way I argued in value-in-use, the literature likes to talk about value co-destruction. This is a misnomer, introduced to parallel the concept of value co-creation. Yet value destruction is not necessarily a joint endeavour. It only requires one actor. Therefore I can’t call it co-destruction.

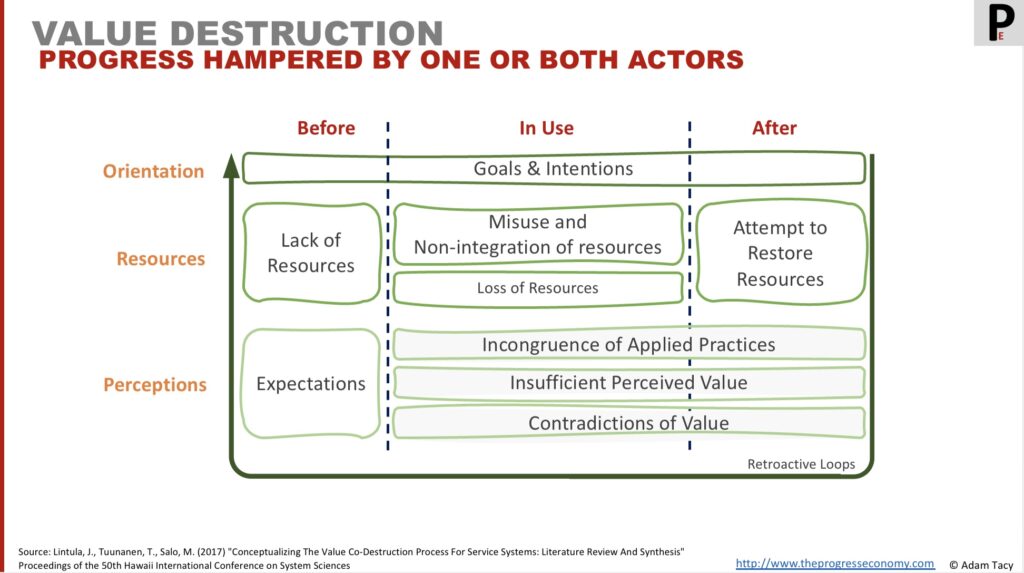

A tool we can leverage is Lintula et al.’s framework for “value destruction”, shown below.

It is useful for understanding contributors to, and timelines of, value destruction. Revolving around orientations, resources, and perceptions; before, during, and after a progress attempt. Experiences gained in an attempt feed back into future attempts (I would add for both seeker and helper). See Lintula et al (2017) “Conceptualizing the Value Co-Destruction Process for Service Systems: Literature Review and Synthesis”.

For example, a seeker might start with incorrect expectations of progress. When these expectations are unmet, they seek someone to blame (usually not themselves). Alternatively, an actor might lose resources mid-service—like an IT consultancy diverting resources to a better contract. Or, a resource might be misused, such as not knowing the need to use a hammer drill rather than a normal drill on a concrete wall to hang up a picture frame.

I’ll shortly reuse the timeline and feedback loop of Lintula et al’s model to frame the progress comparisons made during a progress attempt. It works well to have the same framework.

Before we get there, there’s the observation about emerged and realised value to address.

recognising value

Now we’ve seen value as incrementally emerging as progress is made, let’s turn our attention to if that value is meaningful to a seeker. Which ultimately is a question on whether progress made is meaningful.

To grasp this concept of meaningful, consider you have a functional progress sought of arriving in another city, 400km away. For now we’ll ignore any non-functional progress – such as quickly, scenically, safely etc – and any contextual progress – in rush hour, have no driving license, or similar.

Emerged value, from making progress, is not immediately meaningful to a seeker. To be so, a seeker needs to recognise it – a process akin to revenue recognition. Share on XOn the surface our model tells us value increases the further along the 400km we get. We get peak value (100%) when arriving at the 400km mark. So at any point along the journey the seeker could examine the value that has emerged and say that is meaningful to the them. At, say 300km, they could feel they have 75% of the value. The next time they look, say 332.17km, they feel they have 83.045% value.

If we were to plot this, we would see the first value recognition line on the following diagram. Where value recognition follows value emergence.

So far, no big deal. What if the progress sought included the context of attending a prestigious dinner that evening. How meaningful is reaching 80km now to the seeker? They would still see 80km of value has emerged. But if they are stuck at that point and will miss the meal – perhaps their car has broken down, or they’ve missed a public transport connection – then the meaningful progress, to them, is nothing. Their recognised value is zero. Now we’re looking at the bottom value recognition line in the above diagram, where emerged value is only recognised once reaching progress sought (or offered when engaging a proposition).

The process of recognising value is akin to revenue recognition in accounting. And a seeker has various approaches they may take. Common ones are:

- as it emerges

- on regular schedule/milestones

- at end of each progress-making activity

- on reaching progress sought/offered

The fact that seekers may recognise value on a different timeline to it emerging is insightful. We’ll see that progress reached judgements use recognised rather than emerged value.

Yet we can’t ignore emergence of value since we saw that lack of it is a key indicator of potential value destruction. Whilst we’ll see that seekers generally make commitments to continue progress at the end of progress-making activities, they are constantly building up to that decision and identifying value destruction based on emerged value. Its therefore beneficial, for progress, if a helper can encourage a seeker to recognise value quicker.

Here’s how we’ll depict value recognition in our semi formal notation. Since recognised value usually lags emerged value we’ll use the maths floor function, , to represent it. With the intention that recognised value is the floor function applied to emerged value.

Which given value and progress are the same thing in our model, we could equally write:

Here’s how we’d look at three of the common approaches above:

| approach | formula |

|---|---|

| recognise value as it emerges | |

| recognise value at end of each progress making activity | |

| only recognise value once progress sought/offered is reached |

It’s in the interest of a progress helper to encourage a seeker to recognise value as quickly as possible. When judging the progress they have made, which influences if they feel a desire to continue, seeker’s lean on judgements of recognised, rather than emerged, value..

Let’s now jump into the progress comparisons made before, during and after a progress attempt.

measuring value – before progress attempt – by progress seeker

Let’s start with the value judgements seekers make before a progress attempt. We’ll discuss later the progress helpers progress comparisons and what they mean.

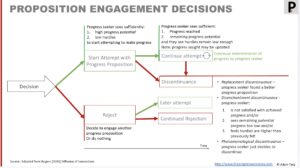

Before attempting progress, a seeker judges if they see sufficient progress potential or if they will proceed alone or seek assistance. The lack of resources progress hurdle plays a role here in their determination. If they feel a need for supplementary resources, they compare offered propositions to find the one that works best for them. Picky, right?

Here’s the value judgements they make:

- a solo progress attempt

- progress potential vs progress sought

- height of lack of resource progress hurdle vs tolerance of lacking resource

- when engaging a proposition (in addition/updating above)

- progress offered vs progress sought

- progress potential vs progress offered

- seeker’s progress origin vs proposition’s origin

- height of five proposition related progress hurdles vs tolerance of those hurdles

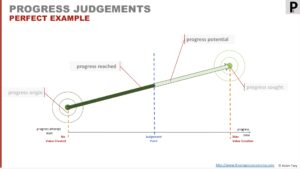

First, a seeker compares their progress sought – remember this is their more desired state – with their expectation of progress potential. They are judging how far they believe they can reach toward their progress sought, with the resources they currently can access.

Written in our slightly formal notation, this is the following value judgement:

Where higher results – the inverse of the distance between progress sought and the seeker’s individual and phenomenological judgement of progress potential – indicate higher potential to reach progress sought. The best judgement is where they believe progress potential matches their progress sought.

Feeding in to the judgement of value potential is the seeker’s view on the lack of resource progress hurdle height. This is the difference between their judgement of the hurdle’s height and their individual tolerance.

This is the “I don’t have time,” “I don’t know how,” “I don’t have the strength,” etc, judgement. It’s the primary driver of lowering progress potential in solo progress attempts.

If the seeker feels high enough potential progress and a low enough lack of resource hurdle, they likely decide to start the progress attempt.

When they don’t, the seeker has a number of choices. They could choose to not start the attempt, deciding to consider a different progress attempt, or doing nothing. Alternatively, they might start this attempt anyway and see where they get. Their final option is to seek a progress proposition that provides supplementary resources.

When engaging a proposition, the seeker looks for one that:

- maximises progress toward their progress sought

- closest aligns with their origin

- or has flexibility to align with the seeker’s origin and progress sought

- has minimal progress hurdles.

The seeker’s first comparison, between a proposition’s progress offered and their progress sought, is as follows:

With a seeker perceiving a proposition that gets them closer to their progress sought as more valuable.

I’ve made an implicit assumption that progress offered is usually less than progress sought given how they are often compromises. That can mean two things for a seeker. First they might embrace that additional progress as something they were not initially aware of, but appreciate. In this case they evolve their progress sought to include all, or the part of interest, of the progress offered.

On the other hand that extra progress might be wasted (unrecognisable) progress if it does nothing for the seeker. In this case the risk is that the equitable effort exchange hurdle is higher than needed due to the extra effort the helper offers to provide that is not valued by the seeker.

Seekers also make a judgement on origins – the starting point of attempts. This is something that will feel obvious once you see it, yet likely was not in your mind before thinking in terms of value-through-progress. Here’s the judgement:

The closer the two origins, the greater the seeker’s perceived value.

This comparison reveals potential under/over resourcing of the proposition and the impacts. If the proposition’s origin is to the right (ahead) of the seeker’s origin then there is either still a proportion of the original lack of resource left and/or a new lack of resource. Say you are a beginner Mandarin Chinese learner and you look at a proposition that assumes you have intermediate level. There is a lack of resource you have that the proposition is not going to help with.

Conversely, the proposition’s origin may be to the left of the seeker’s origin. Now the proposition is over resourcing, and until progress reaches the seeker’s origin, it is not actually creating value. That can frustrate the seeker and/or frustrate them with a higher equitable effort exchange hurdle they don’t need. This is worse if the related progress-making steps are mandatory. You might, for example, be an advanced beginner in Mandarin, but the only provider you find of courses wants you to do their basic beginner course before anything else.

Ideally, a seeker is looking for a proposition that starts at their origin and that helps them reach their progress sought.

They may additionally judge how flexible a proposition is with its origins and progress offered to align closer with theirs. Higher ability to align may override initial judgements on origins and progress offered that are too far away. Although, as we discussed earlier, that often comes with a potential increase in equitable effort exchange progress hurdle.

And it’s not just the equitable exchange hurdle the seeker judges. Now their unique and phenomenological perceptions of all six of the progress hurdles heights are judged against their unique and phenomenological determinations of tolerances.

Intuitively the proposition that offers the lowest hurdles is the most attractive to the seeker.

Don’t forget that the lack of resource hurdle is now concerned with the seeker’s plus the proposition’s supplementary resources together. It may still be the case that the combined resources may not have reduced the lack of resource sufficiently. Or the proposition may have introduce a new lack of resources. For example, a flying car service might improve transport progress, but if you need to learn to fly flying cars, the helper has introduced a new lack of resource.

A seeker also updates their original solo attempt progress potential comparison. Now they compare against the proposition’s progress offered (rather than progress sought in a solo attempt). They are judging how far they feel they can get when engaging the proposition. It becomes:

Like with similar comparisons, a higher result has the perception of higher value.

With all these comparisons comes the question of how the seeker sees them combination of value judgements.

measuring value – seeing the full picture

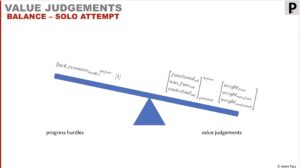

To fully understand a seeker’s view of value, we must consider not only their value judgements and hurdles but also how these interact. Let’s start with the simpler case of a seeker attempting progress on their own and concentrate on the before phase.

Here, the seeker makes two judgments before they begin an attempt: one on their progress potential and another on their lack of resource progress hurdle. Now imagine these as two sides of a balance scale, where ideally, the judgment of progress potential outweighs the judgment of lack of resource. This is what you see in the diagram here.

With this in mind, we can say our progress/value balance is:

On the left is the collapsed seeker’s unique and phenomenological value judgement as we discussed earlier. Over on the right is a similar approach to collapsing their unique and phenomenological judgements of progress hurdles. It is quite straightforward in this case as we have just one hurdle – lack of resources – so it has weight of 1.

We can write this in the less imposing form of:

In general, if the collapsed value () is greater than the collapsed lack of resource hurdle (

), a seeker likely makes the attempt. If not, they likely do not. Although a small number may make the attempt anyway; we’re just wonderfully awkward to model.

And it is here we see the formalisation of our familiar rationale for the existence of progress helpers and progress propositions. They exist to lower the right hand side of the balance through offering supplementary resources, increasing the left hand side (progress potential).

We can simply extend this logic to the case of engaging a proposition. Though it is marginally more complex since we need to take account of the five additional hurdles as well as the three value judgements a seeker makes in this case. Here’s how the balance looks graphically:

The value judgements, of which there are three in the before phase (,

,

), can be further collapsed with the use of some more weights to a single value:

Similarly we can collapse the progress hurdles using appropriately identified weights, that are technically unique to each seeker, for each hurdle:

Our value/progress balance remains as before, with the above more thorough definitions:

As does the intention that if the weighted judgements of value are greater than the weighted judgements of progress hurdles, the seeker sees value in engaging that proposition to make progress.

Further, we can observe seekers using the same logic to choose between propositions. If we take two propositions, A and B, then the seeker feels proposition A is more valuable if the value balance of A is greater than that of B:

Let’s take a quick stock of where we are. We’ve introduced a lot of weights in order to collapse various seeker unique and phenomenological value judgements (progress comparisons) and judgements of hurdle heights. Those collapsed values are then the basis for the seeker deciding to make a progress attempt on their own or to engage a proposition. In the case of the latter choice, the collapsed values show how a seeker choses between propositions.

That’s a powerful, and heavy insight. These judgements, weights, and comparisons are the levers we are looking for to better understand value, and therefore improve innovation.

However, it’s a lot to identify. And this is just the before phase, it is similar for the during and after phases. As helpers we can identify all this for an individual seeker. It just takes effort as a customisable offering; which pushes the equitable effort exchange hurdle higher. We have to introduce some practicality/strategy to our innovation; as we’ll touch on shortly.

It’s also a process that seekers may not immediately recognise they go through on a daily basis. And if we try and engage to identify all these weights, it may adversely affect othe progress hurdles (adoptability, resistance, etc). Although when pushed they may admit to applying heuristics they have learnt in the past, or maybe apply more formally decision processes (pros and cons lists, or formal bid evaluation criteria etc).

Now we’ve covered the before phase from a seeker perspective. Let’s see what it means for the helper.

measuring value – before progress attempt – by progress helper

Have you ever tried buying a new high-performance sports car or luxury penthouse apartment in Manhattan? Chances are that most of us wouldn’t be shown around those goods by a dealer or estate agent as they wouldn’t feel we’d be able to enter into the appropriate level of effort exchange. This is an example of one of the two cases where a progress helper makes progress comparisons.

While the seeker is the one making value judgments, a helper might conduct progress comparisons themselves, in parallel. In the “before” phase, these comparisons help with determining if progress with a specific seeker is a good use of their supplementary resources. They also play an important part when creating or updating their proposition. The progress comparisons they may make are:

- progress potential vs progress sought

- proposition’s progress origin vs seekers’ origin

- hurdle heights

In the first case – when determining if they give access to their resources – a helper is essentially determining if they feel enough progress could be made by a specific seeker so that it results in an equitable effort exchange; and not in stalled progress / value destruction.

For the sake of brevity, I won’t write out the definitions of all these comparisons here; we’ve already seen them above, the difference is we are viewing them from a helper’s perspective. However, it is worth considering the progress hurdle comparison, which typically is as follows:

You’ll notice this is not the full suite of progress hurdles. Hurdles of adoptability, resistance and lack of confidence are not of interest for this comparison (though see alignment step in the during phase).

A helper may judge a seeker has lack of resource even with the supplementary resources they are providing. A good example is the language learning from before; a helper providing only intermediate Mandarin level lessons may decide not to allow a beginner to engage. Or a helper may feel the seeker is looking to engage a proposition too far away on the progress proposition continuum.

These two comparisons are more likely made as the proposition moves towards the relieving and of the continuum. At the enabling end, we might observe a helper does not overly care about a seekers other lack of resource/misalignment on continuum. Those are of course potential opportunities and/or signals that the propositions needs altering if there are sufficient number of seekers with that issue.

Finally we have the equitable effort exchange hurdle. A helper offers their resources to partake in an exchange (direct, or more often indirect through service credits). The helper signals their view of equitable effort required in exchange (price). As such, in certain propositions the helper may wish to judge if the seeker can meet those expectations before spending effort.

When judging progress potential, we can’t forget about external factors – externalities. They, according to our model, insert aspects of progress sought to minimise what society determine as harmful/bad progress. For example, an externality we call government inserts the need for a prescription by a doctor in order to seek prescription only drugs. A pharmacist (helper) checks the seeker has that before fully engaging.

We can take another example, this time from the B2B world. Seekers often send out Requests for Proposals. Helpers decide whether to reply/bid or not. They not only assess if they can help, they also assess the progress potential with that client and the likelihood of a satisfactory equitable exchange. Some clients are tough to work with and effort may be better spent with other clients.

These comparisons are also into play in the second case – when a helper creates or updates a proposition. Now they are judging how well, do I as a helper, think my proposition help a seeker?

It ‘s interesting to note that what a helper eventually calls their progress offered can be seen as their view of progress potential.

Without these comparisons, a helper may find it challenging to understand if their proposition is viable and/or how to improve it – innovation – and what improvement means This highlights the need for a helper to truly understand their seeker, their seeker’s progress origin and progress sought as well as the value judgements the seeker will make.

Although TV shows like Dragon’s Den (or Shark Tank in the US) suggest that novice helpers often fail to do this. And your experience might indicate that it’s not just novices who struggle. It’s certainly noted in multiple studies that “lack of market fit” is a key contributor to startup failures.

To achieve this level of understanding a seeker’s progress – which remember is unique and phenomenological to a seeker – points to offering highly customised offers. However, that increases effort, leading to a higher equitable effort exchange hurdle (lazily: price). A way to strategise against that is segmentation. That is to say, offering “close enough” progress at “acceptable enough” levels of hurdles. That strongly points to segmentation not based on traditional approaches such as demographics (sex, age, location etc).

Incidentally, what you as a helper perceive as progress potential of your proposition is better known as progress offered.

If we get to the point where a seeker and helper decide to engage, we shift into the during phase. The next step maybe one of aligning the proposition to the seeker’s progress attempt.

editing from here down

increasing potential value – aligning proposition

At the start of the during phase of a progress attempt there is potentially an aligning step.

The degree of alignment varies depending on the proposition and the helper and, in some cases, might not occur at all – you get what you are given. This could be due to an oversight by the helper (which presents an opportunity) or other reasons. Interestingly, our model provides insights into the variation, which we will discuss soon.

The primary benefit of alignment is to close the gaps between origins as well as progress sought and progress offered. This could involve helping the seeker realize that their progress sought might exceed what they truly need. It also looks at reducing progress hurdles. It offers the customisation Vargo & Lusch advocate for in “The Four Service Marketing Myths”. The goal, ultimately, is to increase the potential value (or progress) of the attempt to the seeker and secure an exchange for the helper.

Alignment is an in-line process, tailored to each seeker and attempt. It operates independently from any dedicated out-of-line innovation process but should inform any such processes if the alignment proves beneficial.

When aligning, the helper should look to achieve some combination of:

- aligning more closely with the individual seeker’s progress origin:

- aligning more closely with the individual seeker’s progress sought:

- reducing a seeker’s judgement of progress hurdles to be closer to the individual seeker’s tolerances:

Sometimes, the alignment process may lead the seeker to adjust their progress sought. They might learn their initial progress sought is beyond their actual progress needs, or they might identify new progress aspects they hadn’t previously considered.

Since a helpers objective is to obtain service exchanges, it is generally in their interest to take advantage of an alignment step. As Vargo & Lusch say “the normative marketing goal should be customisation rather than standardisation”.

Despite Vargo & Lusch’s recommendations, we acknowledge that an alignment step isn’t always practical or wanted. For instance, when purchasing something simple like a nail, an alignment step seems excessive.

Our value-through-progress model helps explain why; an alignment step shifts the proposition’s progress origin to the left.

This is beneficial if the proposition’s origin remains to the right, or even tolerably to the left, of the seeker’s origin. It allows for the necessary adjustment of resources without overly impacting other progress hurdles.

However, if the proposition’s origin moves too far left of the seeker’s then there are impacts. First the over resourcing means increased effort, which likely pushes the equitable effort exchange progress hurdle up. Secondly, the seeker starts to perceive too much progress needs to be made before any value starts emerging. Finally, we must consider the resistance progress hurdle, particularly regarding the traditions & norms and usage patterns aspects. Those could lead to a seeker rejecting a proposition.

Returning to the nail. Imagine having to have a consultation on how you intend to use it before you’re allowed to buy it. That’s going to cost you more, is against how you expect it to be done, and is wasting your time (hindering progress, which ultimately leads to value co-destruction).

Once any successful aligning is performed the seeker now begins to attempt to make progress from their progress origin.

measuring value – during progress attempt

Now let’s look at progress proper. In this step of the during phase, value begins to emerge as actors integrate resources and progress is made towards progress offered/sought coming out of any alignment step.

Here’s a quick reminder of the progress comparisons that occur during a progress attempt. As in the previous phase, some comparisons apply to solo attempts, while additional or updated comparisons occur when a seeker engages a progress proposition.

- a solo progress attempt

- value recognition

- progress reached vs progress expected

- (remaining) progress potential vs progress sought

- height of lack of resource progress hurdle vs tolerance of lacking resource

- additional when engaging a proposition

- (remaining) progress potential vs progress offered*

- height of five proposition related progress hurdles vs tolerance of those hurdles

We’ve just discussed the first item, value recognition, above. That’s where a seeker converts emerged value into value that is meaningful to them. Let’s look at a couple of comparisons that go hand-in-hand. Seekers regularly compare their progress reached vs. progress expected and their remaining progress potential vs. progress sought.

You can see how these two interplay on the diagram here. As an attempt moves forwards in time, seekers judge how much progress they have realised against their expectations. Am I where I thought I would be? Alongside this, they assess how much progress they believe they can still make. Do I still feel I can get where I want to?

These judgments are unique to each seeker and phenomenological. We see them as judged together, allowing for situations where a seeker feels they have not reached where they expected yet, but they still feel they have the potential to reach their more desired state later.

In our notation, is:

Where higher results imply positive views of value, and results greater than the maximum on scale you are using, indicate realised value has exceeded expectations at that point in time.

The paired comparison of remaining progress potential, , is:

Since we expect the seeker to become wiser during an attempt we also expect they update their judgement of progress potential, and perhaps progress sought. They learn from their current attempt, and from other attempts in other markets and industries they are progressing in parallel. This is why our comparison are of these states at the cuurent tine, ie rather than their initial

.

Comment on earned value?

Along with these comparisons seekers judge their lack of resource progress hurdle at this tine. Again, as they progress their judgment of hurdle height, and their tolerance, can change from their original due to experiences. They may identify a higher, or lower, hurdle than at the start.

If a seeker judges insufficient progress has been realised, their is insufficient remaining potential progress, and/or lack of resource hurdle is too high, they may abandon the progress attempt.

What happens when a seeker engages a proposition? In such a case, judging the value reached remains as above. It’s hand-in-hand comparison, remaining progress potential, evolves to be a comparison against the proposition’s progress offered (instead of progress sought). It is:

With, as usual, larger results implying greater potential value. We still expect the seeker to become wiser under an attempt so their view of progress potential will evolve against an evolving progress sought.

What we may additionally see is the helper evolving their progress offered during the attempt. That evolution comes from the interactions they are having with the seeker. Our proposition continuum comes in useful here. It leads us to an insight that in-line progress offered evolution happens less at the extremes than in the middle. Since there are fewer interactions.

And this is what we observe. Consider a nail (enabling) or logistics transportation (relieving); there is little interaction during progress and subsequently little in-line evolving of progress sought.

As a result of these progress state evolutions the seeker continually rejudges the progress offered against their progress sought. If this value judgement becomes too low the seeker may abandon their attempt.

In parallel, seekers judge all six progress hurdles compared to their tolerances. Since these can change over time, the comparison is at the current time:

This discussion of regular value judgements raises an interesting question. When does a seeker make these judgements?

Knowing when a seeker makes value judgments provides opportunities to gain valuable insights into potential value destruction and abandonment decisions.

For solo attempts, this is largely academic. Although might feed into marketing of propositions – “are you always getting stuck at this point? Our exciting proposition gets you going…”. However, when a proposition is involved, it provides the helper with timelines of opportunities to engage with the seeker to minimise frustration, value destruction, and, abandonment

It’s tempting to think the timing of value judgements aligns with a seeker’s value recognition schedule. But there’s a subtle difference between the concepts.

Value recognition relates to “banking” emerged value. It’s a trailing metric of value. Yes it is a value judgement, but it’s rather like clipping your rope whilst scaling a mountain. The other value judgements – reached, remaining potential, and, hurdle heights – create that unique and phenomenological prediction of future value that drives a seeker’s decisions. As such, those judgements happen quite regularly; but a seeker may not act upon them immediately. I represent that n the bottom row of thefollowng diagram.

Consider again our value recognition toy example of travelling 100km to attend a prestigious dinner that evening. You will not wait until getting to 80km before judging your potential to get the remaining 20km is zero. If you’re like me, you will have been aware of that earlier. Initially as a niggling thought which then grows as judgements indicate lower potential to meet my progress sought. At some point, you will try to do something to address any shortfall in predicted progress. The most impactful option being to abandon the attempt.

The skill of a helper lies in knowing when to check in with the seeker to understand their judgments and how to respond. Practically, we can assume these value judgments occur at or near the end of individual progress-making activities, with the caveat that they may occur more frequently during long or difficult activities. “Long” and “difficult” are subjective terms, requiring the helper’s skills and knowledge to assess, possibly in collaboration with the seeker.

During the attempt, much like in the before phase, a helper may independently make progress comparisons about a specific seeker. Typically they compare:

- progress reached by seeker vs expectations of helper

- remaining progress potential vs progress offered

- progress sought vs progress offered

These comparins are not considered value judgments, as only the seeker can make those, nor do they directly influence a seeker’s value judgments. Instead, the helper uses the to understand two key aspects: First, whether the progress reached meets their expectations – if not, value destruction might be occurring. Secondly, whether the remaining progress potential is sufficient. These comparisons are of the standard format:

Based on their comparisons, the helper might decide to add additional resources to recover from value destruction. Alternatively, they may withdraw resources if they view continuing the attempt as a waste, likely causing the seeker to abandon their effort.

A helper may also compare the current progress sought with the current progress offered. As we’ve seen, progress sought can evolve as a seeker attempts progress in the current effort and in others they pursue in parallel. A helper might choose to look for these changes and update their progress offered accordingly. They might also, independent of seeker, identify ways to enhance their offerings and look to see whether the seeker will find these updates valuable (i.e. update their progress sought).

Timings of comparisons is the same discussion we just had with seeker value judgements. With the addition that comparisons are less likely at the enabling end of the progress proposition continuum than nearer the middle. The reason being there is less interaction there.

Assuming the seeker reaches the end of a progress attempt, there is a final phase of measurement.

measuring value – after progress attempt

We’ve made it to the end of a progress attempt!

Hopefully congratulations are in order as the seeker has reached their final view of progress sought, or progress offered if engaging a proposition. Although we could be here because a seeker has abandoned their attempt early.

Either way, there are some final progress comparisons made. Essentially determining if the attempt was worth it. The comparisons made are:

- a solo progress attempt

- progress reached vs progress sought

- lack of resource progress hurdle height

- additional when engaging a proposition

- progress sought vs progress offered

- height of equitable exchange hurdle

- potentially height of five proposition related progress hurdles vs tolerance of those hurdles

Let’s start as usual with the seeker’s progress comparisons, which we also see as value judgements. On a solo progress attempt they judge whether this attempt has been valuable to them. Did they reach their progress sought.

Whether progressing alone or with the help of a proposition the seeker makes a final judgement of progress reached. In the first case it is against progress sought and the latter against progress offered.

As usual, lower values imply lower perception of value.

Having engaged a proposition it’s not uncommon for a seeker to make some final judgement on whether they got a fair (equitable) exchange. So we see them making a final judgement of the equitable exchange progress hurdle.

With the interpretation being that they are making a unique and phenomenological comparison on the effort they needed to (or will need to) expend in providing a service to get the service they wanted.

They may compare the remaining hurdles as well

Similarly, a seeker judges progress sought against offered in the after phase.

It’s these judgements that may push the actor into any value destruction in the after phase. They also feed back into future progress attempts.

Now we reach the after phase. Here a helper may judge progress reached and hurdle heights to gain insights into how to improve their proposition. They may even try to obtain the seeker’s view. Anyone familiar with those “how did we do?” email questionnaires or hitting one of five smiley face buttons has been a participant of that!

feedback loops

Last, but not least, all the judgements we make during an attempt may feedback into judgements on future attempts.

In particular those reflective judgements made in the after phase.

As Christensen reflects in his Jobs to be done theory, a customer makes an initial big hire (of your service) and subsequent little hires (rehires). These feedback loops play a factor in those little hire decisions

They may also feed back into seeker’s decision on different attempts. For example a good experience with you as a helper may lower their future judgement of lack of confidence progress hurdle with you in an unrelated attempt.

Now it’s time to address the conceit we’ve been using so far: that judgements, and therefore comparisons, are often subjective and non-numerical.

seeker decision processes

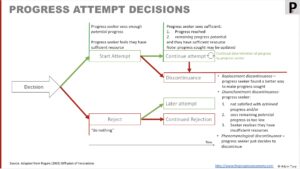

One very useful outcome of the above discussion is we can describe the decision process a seeker uses when making a progress attempt.

This is the process they use when making an attempt on their own, ie without engaging a proposition. Those with a background in innovation may recognise the close similarity to Rogers innovation adoption process. That is no coincidence.

When a seeker engages a proposition, the decision process expands. It builds on the above, adding additional value comparisons.

In both cases we observe three reasons a seeker may abandon an ongoing attempt:

- replacement – they’ve found a better way

- disenchantment – they’re not happy with progress (reached or potential)

- phenomenological – “just because”

Let’s progress together through discussion…