Chasing value often disappoints

OK, here’s the problem. The value-in-exchange model is showing strain.

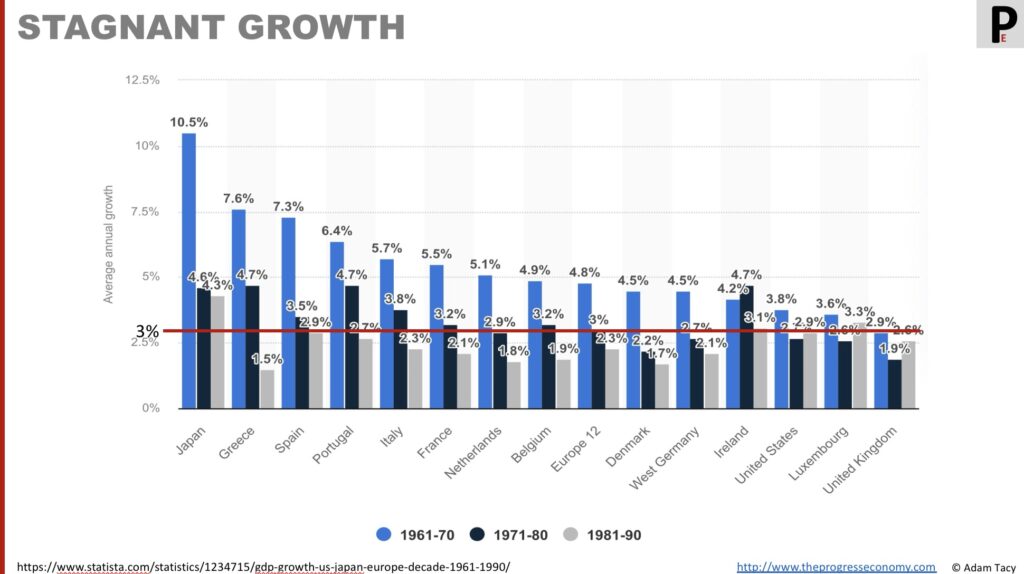

Despite the explosive growth we saw earlier from Adam Smith’s time, if we zoom in to recent years, growth has slowed/stagnated. The International Monetary Fund warns that we may be entering a decade of structural stagnation — the “Tepid 20s” their chair called it.

The world is facing a decade of stagnation – the “Tepid 20s”.

Chair of International Monetary Fund

Executives remain frustrated by the poor returns on time, energy, and capital invested in innovation programmes that promise much but deliver little. McKinsey notes that only 6% of executives are satisfied with their innovation efforts. That means 94% are dissatisfied!

Only 6% of executives are happy with their innovation initiatives

McKinsey

Think how many of your own innovation initiatives have truly delivered the growth you were looking for, or that have become what Steve Blank calls: innovation theatre?

Why? It is our addiction to value:

- value is hard to define and agreement on any definition amongst stakeholders is harder still; we begin to merge value and price, missing many aspects

- there are many blindspots in the value-in-exchange model; these are becoming increasingly important as we search for future growth

- the manufacturing heritage shapes our definitions – and the activities they drive – are mismatched to the service-based nature of our modern economies

- focus accidentally becomes internal with a belief the manufacturer determines value, setting it as price

- we end up tempted into performing Innovation theatre

Lets crack each of these open in turn.

Defining value is hard

Value is hard to define and agree upon; unsurprisingly, activities based on a confused definition lead to poor performance

Value feels easy to define, until you start thinking about it. Then it becomes difficult to define, inconsistently measured, and assessed primarily from the supplier’s/manufacturer’s perspective.

Its definition has a long history of discussion. Grönroos reminds us that “value is a concept that is difficult to define.” Back in 1776, Adam Smith distinguished between two forms: value in exchange – the power to purchase – and value in use – the utility an object provides. Karl Marx observed in 1886 that seventeenth-century English writers made a distinction, using worth to describe value in use and value to denote exchange value. More recently, in 2013, Karababa and Kjeldgaard catalogued a proliferation of competing value concepts, each “lacking a definitive basis.”

…use value, exchange value, aesthetic value, identity value, instrumental value, economic value, social values, shareholder value, symbolic value, functional value, utilitarian value, hedonic value, perceived value, community values, emotional value, expected value, and brand value…

Karababe, E. and Kjeldgaard, D. (2013) “Value in Marketing: Toward Sociocultural Perspectives”

…are examples of different notions of value, which are frequently used without having an explicit conceptual understanding in marketing and consumer research.

No wonder Anderson and Narus observed:

remarkably few suppliers in business markets are able to answer…questions like…How do you define value? Can you measure it?

Anderson and Narus (1998) ”Business Marketing: Understand what customers value”

The problem is straightforward. If we define innovation as the pursuit of adding/creating value – but neither we nor our customers can clearly define, agree on, or even understand what that value is; why should we be surprised when innovation efforts fail?

Not seeing the blind spots

The value-in-exchange model has numerous blindspots; these are becoming increasingly important

There’s no doubt that the value-in-exchange model has been wildly successful. It powered centuries of industrial and economic expansion, rewarding firms that produced efficiently, priced competitively, and exchanged effectively.

But it carries numerous blind spots – before, after, and across the point of exchange. For example:

- Prioritising consistency over customisation – missing value before exchange

- Chasing the next transaction – missing post-exchange value

- Valuing new exchanges over circular thinking – missing value across the exchange

- Elevating goods over services – narrowing the solution space

- Falling into marketing myopia –

- Favouring simple exchange over more innovative business models

- Assuming providers define value

For much of the 20th century, these blind spots didn’t seem to matter. Or in some cases were seen as an advantage, such as prioritising consistency over customisation to drive down unit costs. But today, we may have run out of space to ignore them.

A prime example of a blind spot is sustainability. Under a value-in-exchange mindset, a manufacturer’s economic incentive ends at the point of sale. There is little motivation to design for durability, recyclability, or long-term impact. In fact, the opposite often applies: short product lifespans drive repeat purchases and higher turnover, even as they increase environmental cost.

Consider Gillette’s “razor and blade” model, often celebrated in business schools as a masterstroke of recurring revenue. The firm sells the razor handle at low cost, then captures margin through a continuous stream of blade replacements. Financially elegant, but is it best environmentally? The business model encourages disposability rather than durability.

The same dynamic can be found in fast fashion, where value is extracted through high volume and low price, with little consideration of the environmental or social aspects.

Mismatching to ACTUAL EconomY composition

We’re navigating innovation using an out of date map

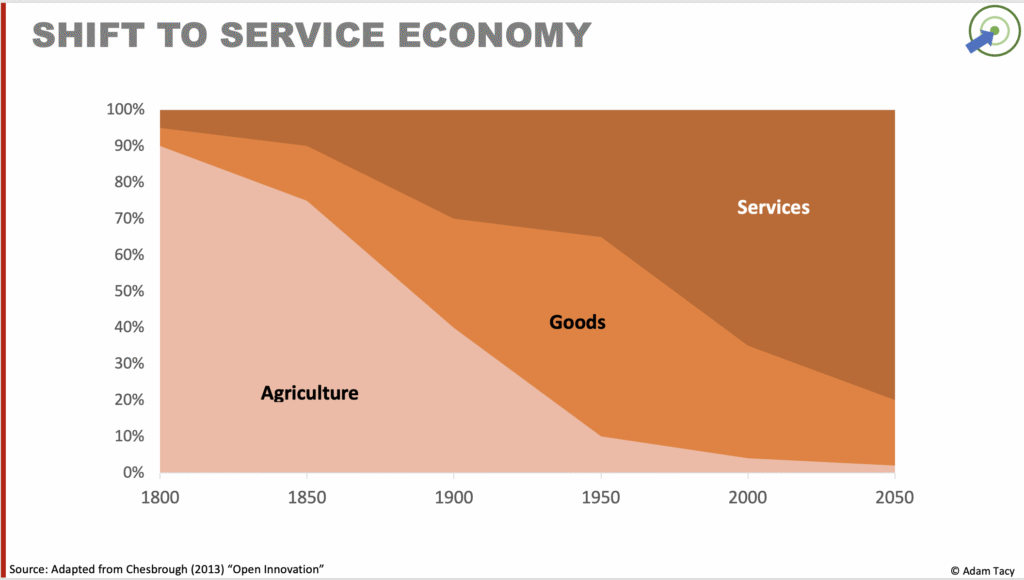

Our traditional value-in-exchange model is deeply rooted in observations drawn from manufacturing and goods. That made sense in an era dominated by industrial production, physical outputs, and efficiency at scale.

Today, it is increasingly misaligned with economic reality.

As Chesbrough notes in Open Innovation, the structure of our economies has shifted dramatically. Manufacturing’s share of GDP has fallen, while services have expanded rapidly—not only in mature economies, but across emerging markets as well.

The World Trade Organization makes the point plainly:

The services sector today generates more jobs (50 per cent share of employment worldwide) and output (67 per cent share of global GDP) than agriculture and industry combined – and is increasingly doing so in economies at earlier stages of development

The future of trade lies in services: key trends, World Trade Organisation

We’ve tried to force services to fit into this manufacturing/goods derived model. This legacy produces the familiar distinction between goods and services, often expressed through the so-called “five I’d”. Services are:

- intangible – services cannot be physically held or inspected before purchase

- inconsistent – quality varies by instance, context, and provider

- inseparable – production and consumption often occur simultaneously

- require involvement – services typically require active customer participation

- cannot create an inventory – services cannot be stored for later use

These differences have led to a lingering goods vs services mindset. Where goods are perceived as stable, tangible, and valuable, while services are seen as variable, transient, and somehow lesser. This stretches back to Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations where value in use (services) were not contributing to GDP growth. At the time, of course, service was maids, bottlers, cleaners etc.

With two-thirds of global economic value now coming from services, the question becomes inescapable: is a model of innovation built for goods still viable in a world dominated by services? Are we navigating innovation using an out of date map?

Too much internal focus

Seeing price as a proxy of value promotes us to become inward focussed

Sadly, a simple definition of value permeates into our thinking and twists our innovation approaches. McKinsey wrap up this easy definition as follows, tying it to the greatest amount a customer is willing to pay::

A product’s value to customers is, simply, the greatest amount of money they would pay for it.

Golub, H., and Henry, J. (1981) “Market strategy and the price-value model” via “Delivering value to customers”, McKinsey (2000)

That simple thought drives our focus to be internal: how can we increase the price. We might argue the market research, focus groups, and so on, help us. But for many organisations, inward focus has become the default. As Clayton Christensen observed, most marketing leaders agree with Levitt’s warning about marketing myopia, yet few act on it.

People don’t want to buy a quarter-inch drill. They want a quarter-inch hole

Levitt (1960), Marketing Myopia

Despite acknowledging this truth, organisations continue to interpret markets through the lens of what they already sell. Segmentation, surveys, and A/B tests are built around existing categories and consumption patterns. The result is a closed feedback loop: new features are inspired by what customers already buy, not by what they are truly trying to accomplish. Innovation risks becoming incremental, at best. At worst you add yet another blade to the razor cartridge.

Much of this stems from how modern firms were built. They evolved in an era when competitive advantage came from producing efficiently. Systems, incentives, and accounting frameworks were all tuned to outputs – products, features, volume, and margin – rather than outcomes. This production bias traps attention inside the firm: what we can make, how we can make it cheaper, and what we can sell next.

The problem compounds through measurement. What gets measured gets managed – and most innovation metrics still track internal effort or pipeline activity: R&D spend, patents filed, prototypes built, and launches completed. These indicators show what the organisation has done, not whether it has made anyone’s life better. Even “customer satisfaction” scores tend to reflect delivery performance, not genuine progress in the customer’s world. The link between innovation and growth, between innovators and the business is missing.

The consequences are familiar — Kodak, Blockbuster, and countless others that confused more with better.

Performing Innovation theatre

an inwards focus and acceptance the “innovation is hard” tempt us into innovation theatre

A consequence of the above – combined with a belief that innovation is inherently difficult and a quiet acceptance of poor outcomes – seeps into all those innovation activities you sponsor: the hackathons, ideation competitions, brainstorming sessions, open innovation, and so on.

oo often, these efforts slide into what Steve Blank calls innovation theatre: activities that feel energising internally and look impressive in shareholder or marketing reports, but produce little in the way of tangible results. No new customers, no meaningful cost reduction, and no sustained growth.

When our innovation activities deliver few/no tangible results, we are performing innovation theater.

Steve Blank (2019) “Why Companies Do ‘Innovation Theater’ Instead of Actual Innovation”

How many hackathons, ideation competitions, and brainstorming sessions have you sponsored, only to see few (if any) tangible results? How confident are you that your organisation even shares a common definition of “innovation success”, or looping back to my first point, understands what customers truly value (whatever that might even mean)?

Are you excusing the innovation theatre in your organisation as “but, innovation is hard”, or “the next hackathon will be the one that changes our fortunes”? It’s your definition of innovation, based on an undefinable concept of value, that needs to change.

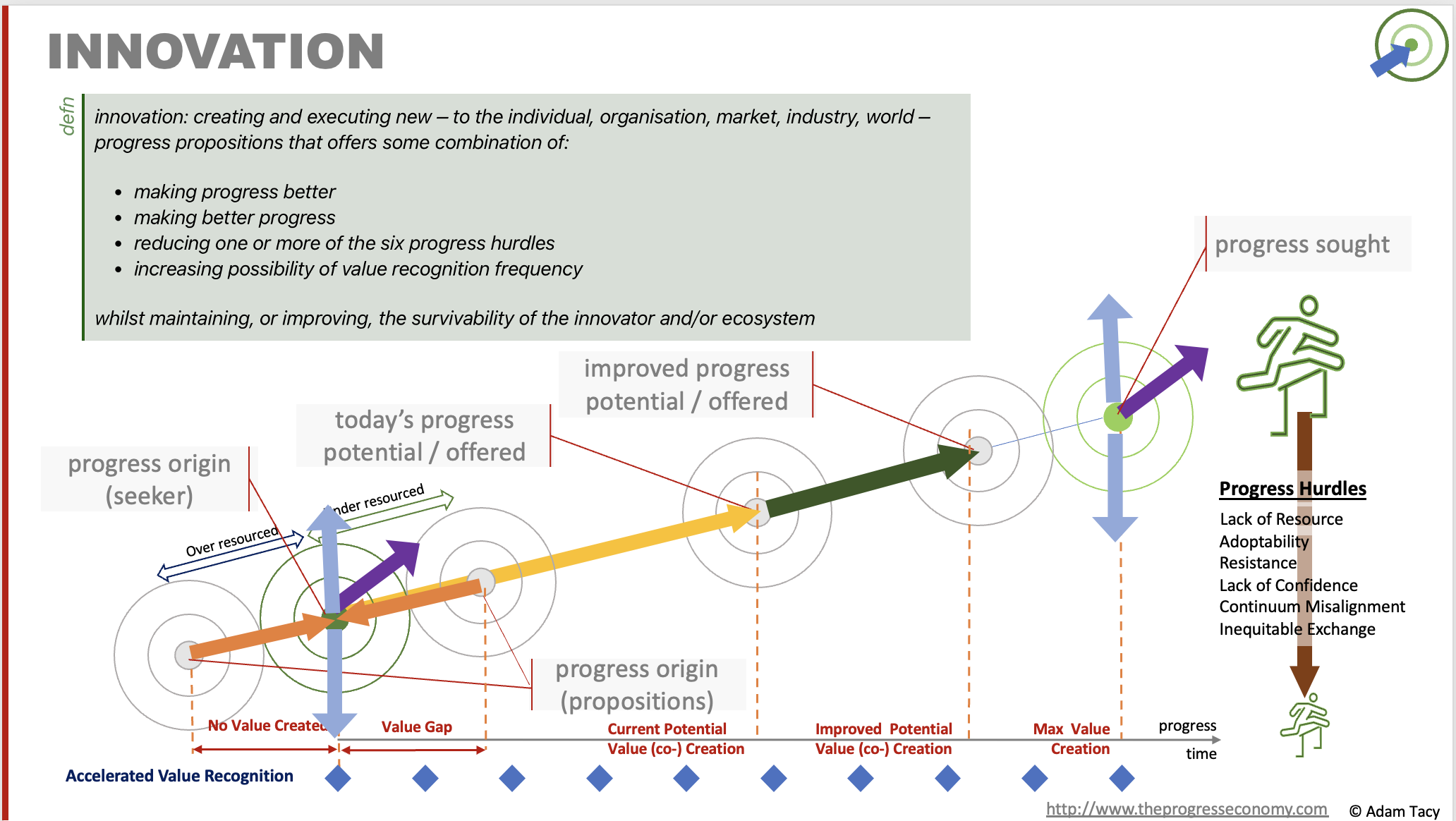

The innovation problem is structural: the wrong endgame (adding value), the wrong mental model (value-in-exchange), and the wrong success lens (supplier-centric rather than Seeker-centric).

This is something we can fix by shifting our focus of innovation to one of enabling better progress, which improves well-being (comparisons of progress). And that’s what we’ll explain next.

Let’s progress together through discussion…