Insights from the Progress Economy

If chasing value is problematic to innovation and growth, what can we do? This is where the two shifts inspiring the progress economy come in:

- value – an increase in well-being – emerges “in use” rather than being embedded and exchanged

- “in use” means making progress to a more desired state; well-being is comparisons of progress

Let’s look at those two shifts and then the positive implications they bring on how we define innovation.

Value (well-being) emerges in use

The first shift is observing, as Grönroos did, that value isn’t embedded and exchanged, it emerges when we use goods and services.

…value really emerges for customers when goods and services do something for them.

Grönroos (2004) “Adopting a service logic for marketing”

When you use your car to drive somewhere, value emerges as you are using it. Whilst it is sitting in your garage it has only potential value. As we use a product or service we are attempting to improve well-being, something that cannot be exchanged.

This is the value-in-use model and it offers the potential to minimise the blind spots of value-in-exchange. But it still leaves us with a challenge: defining, and agree on, well-being.

In-use means making progress; well-being is progress comparisons

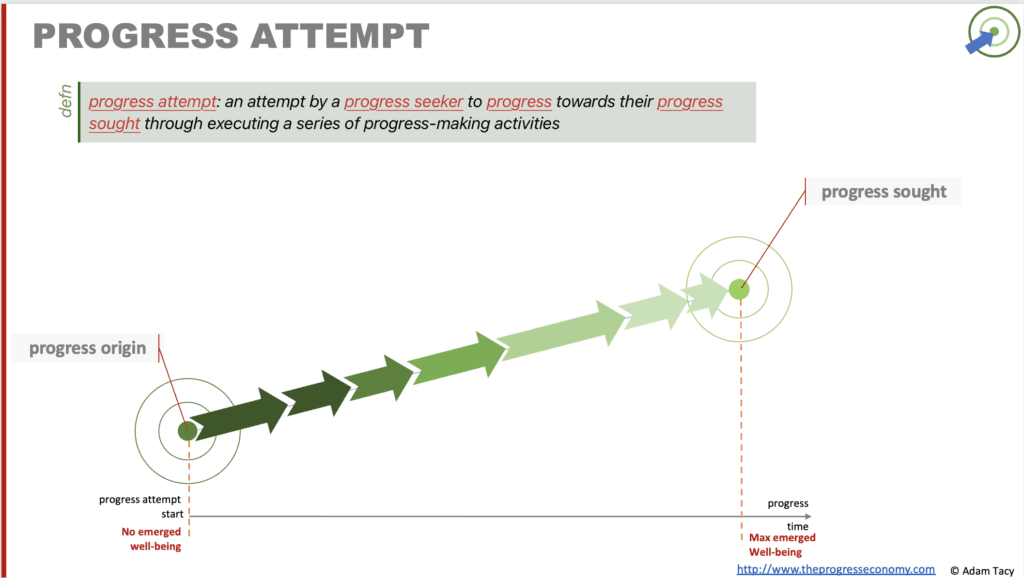

The second shift is identifying that “in-use” relates to making progress over time to a more desirable state. Progress is the action that improves well-being; and well-being is a set of progress comparisons. When your progress reached, for example, matches your progress sought then you have maximised the improvement in your well-being.

- B2B: Cloud infrastructure providers did not simply offer cheaper servers – they enabled businesses to scale without owning data centers (aligning to progress sought), shifting capital expenditure to operating expenditure and reducing operational risk (lowering progress hurdles).

- Public sector: Digital identity programs don’t just improve “efficiency” – they help citizens progress through life events such as opening a bank account, accessing healthcare (aligning to progress sought) with less administrative friction (aligning to progress origin and reducing progress hurdles; though digital ids can increase the resistance progress hurdle if not managed).

- B2C: Streaming platforms did not just add “value” over DVDs – they removed friction from the progress of accessing and enjoying entertainment (aligned with progress sought)

These shifts allow us to build a useful model of the economy.

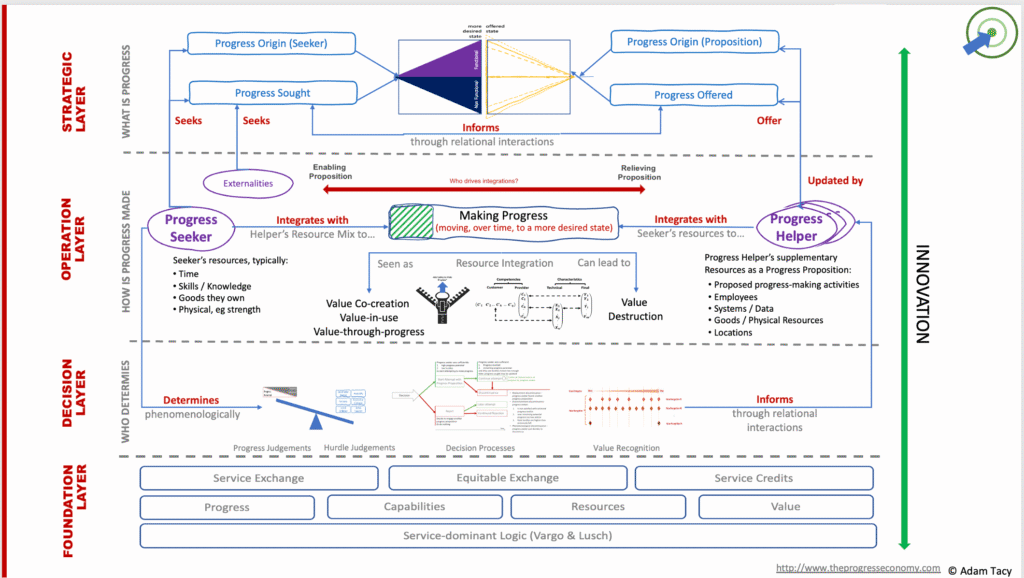

Progress – an operating model for the economy

Taking a progress view of the world reveals an operating model that both builds on value-in-use’s minimisation of value-in-exchange challenges and gives us clear, definable, view of “value creation” (making progress) and how “value” (progress comparisons) can be measured.

The progress economy works this way:

- all actors are seeking to make progress with all aspects of their life

- progress is made by one or more actors applying capabilities through resource integration

- comparing progress leads to judgements of well-being – potential increase, emerged increase, realised increase etc.

- progress is hindered by lacking necessary capabilities (the foundation progress hurdle)

- there is an uneven distribution of capabilities across actors (creating a market for exchanging, often indirectly)

- some actors offer their capabilities to others (as progress propositions)

- progress propositions lift five additional progress hurdles (adoptability, resistance, misalignment on continuum, lack of confidence, and inequitable exchange)

There are three implications of this:

- improving the definition of innovation

- identifying a set of levers we can systematically use in innovation activities to compete against luck

- realising innovation and sales are two sides of the same coin

Improving the definition of Innovation

Innovation is reframed from “how do we add value?” to “how do we improve well-being?” which itself is “how do we make (or help others make) better progress?”.

Now we leverage the operating model of progress to discover four innovation outcomes:

- making better progress

- making progress better

- reducing one or more of the progress hurdles

- accelerating possibility for well-being recognition.

Innovation becomes the disciplined discovery and execution of new ways for Progress Seekers to make better progress, with lower progress hurdles, and quicker value recognition. More formally:

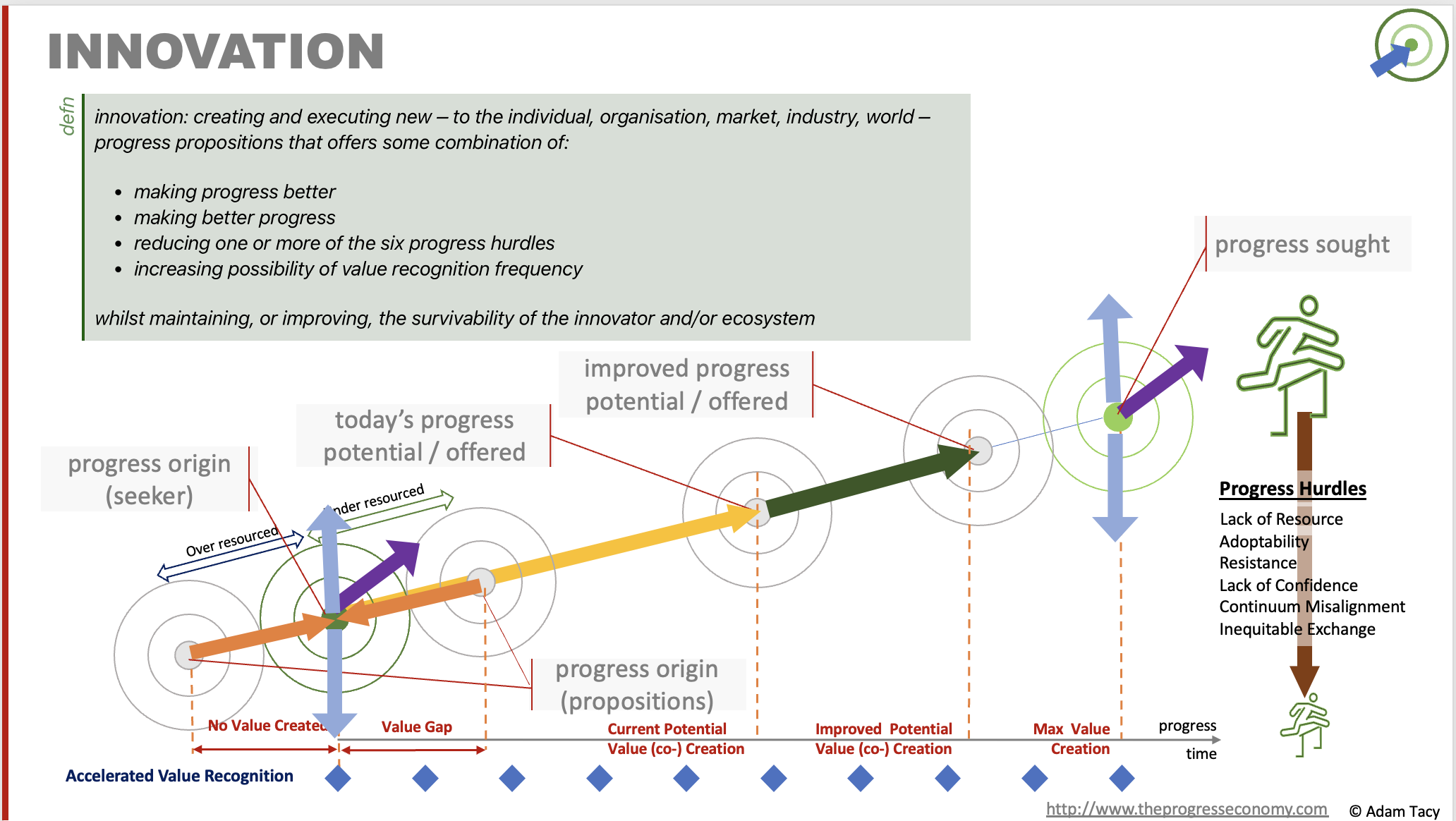

innovation: creating and executing new – to the individual, organisation, market, industry, world – progress propositions that offers some combination of:

- improving progress towards progress sought

- making today’s progress better

- reducing one or more of the six progress hurdles

- accelerating possibility of well-being recognition frequency

whilst maintaining, or improving, the survivability of the innovator and/or ecosystem

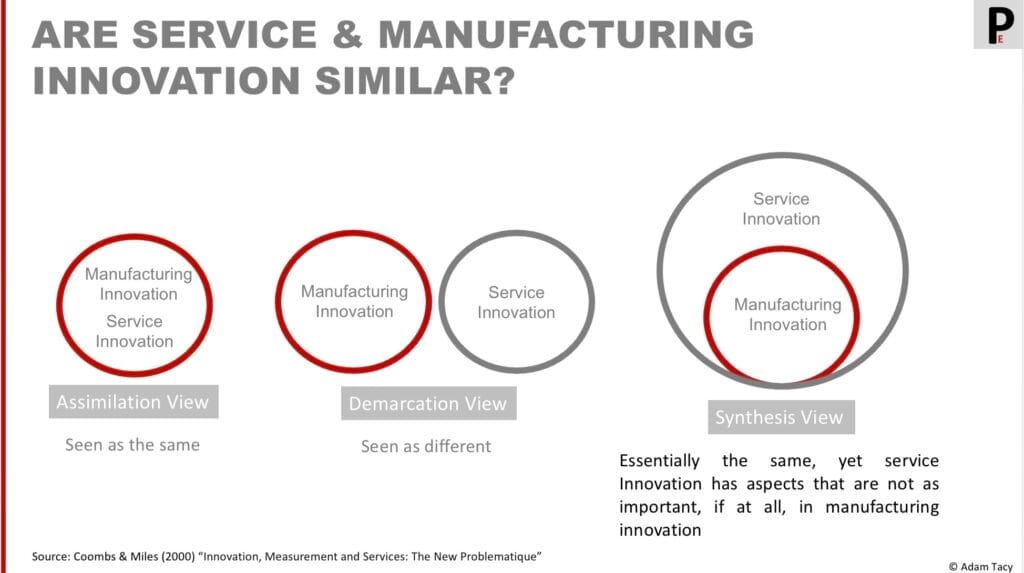

This entails shifting from our familiar foundations based on manufacturing and goods. Does that introduce issues? It’s a conversation discussed in the literature, in particular the divisive goods vs services debate. Coombs & Miles introduced 3 ways to consider this: the assimilation, demarcation and synthesis view.

Coombs & Miles (2000) “Innovation , Measurement, and Services: the new problematique”

Assimilation view services are essentially the same as goods, so existing innovation models apply Demarcation view services are fundamentally different and require distinct theories and tools. Synthesis view services and goods share underlying principles, but service innovation introduces new aspects that are less relevant (or absent) in manufacturing

The progress economy best fits into the synthesis view. In that innovation for goods and services have underlying principles they share. However there are new aspects for services that are less relevant to goods. That is, our view of innovation is broader than just goods innovation.

In fact, we see goods as distribution mechanisms for service.

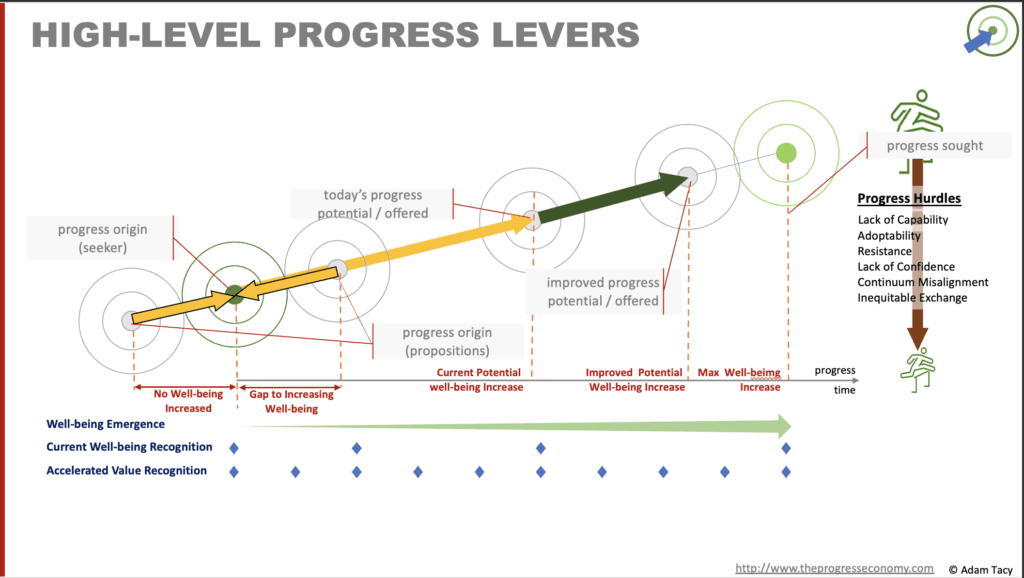

Revealing actionable levers

These four innovation outcomes are high level progress levers – aspects where we can best focus our creativity to identify progress improving activities.

The operating model, and context hierarchy, help us discover numerous lower level progress levers that support those four outcomes. These dramatically increase the odds that innovation efforts convert into successful outcomes.

We are no longer “competing against luck“.

Realising sales and innovation are two sides of the same coin

The last, perhaps surprising, implication of our progress-forward thinking is the distinction between sales and innovation dissolves. Look at the four outcomes in our definition – making better progress, making progress better, lowering hurdles, and accelerating well-being recognition. Are they not the same outcomes you expect a successful sales approach to offer customers?

Innovation operates more “off-line” to design new ways of helping, whereas sales operates “in-line” to match those ways to real Seekers in real contexts.

In fact, sales interactions often generate local innovations and market intelligence that, when captured, can directly strengthen innovation upstream.

Sales and innovation are two sides of the same coin.

Let’s progress together through discussion…