Beyond Value Podcast Episode:

Is, as I claim, chasing value really the problem holding back innovation and growth? Let’s explore today’s circumstances and why we need to be transforming innovation in order to fulfil Christensen’s urge to compete against luck.

What we’re thinking

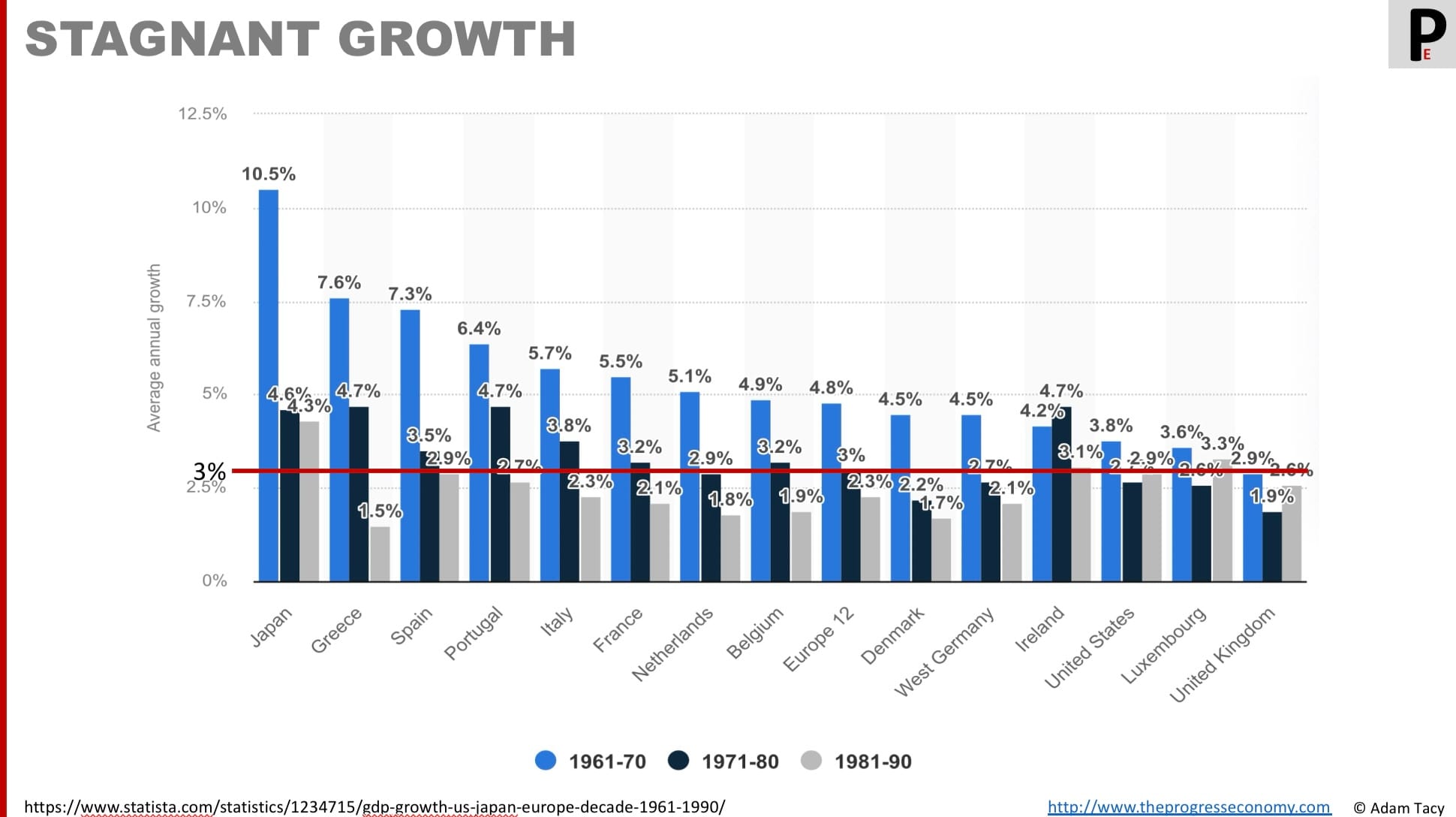

Our innovation problem has seen our previous explosive growth slip into economic stagnation. I make the bold claim that the reason is our obsession with chasing value; for four reasons:

- value is hard to define, agree upon, and measure

- value-in-exchange becomes our prime driver – we obsess with making the next (cash) exchange

- the value-in-exchange model has numerous blindspots – before, after, and across thee exchange – that are becoming increasingly impactful

- despite value-in-exchange having been wildly successful it is based on goods-dominant economy observations and we’re now living in a service-dominant world

We are navigating the world of innovation using an incomplete map to a destination we rarely agree on.

To solve, we must evolve our value model and definitions, practices, and approaches that are based upon it. We need to shift away from adding and exchanging value toward enabling progress that improves well-being – a perspective that makes innovation operational, systematic, measurable, and actionable.

Why this matters

A focus on:

- well-being: decouples us from our value exchange thinking – exchanging well-being makes no sense

- improving well-being: expands us into value-in-use thinking – expanding the timeline of interactions, reducing the blindspots, and to view a wider solution space to look at outcomes rather than outputs

However, we risk “well-being” replacing “value” as being hard to define, agree upon and action.

We’ll solve that by noting that progress – moving over time to a more desired state – operationalises well-being. Making progress improves well-being, well-being is comparisons of progress. Out of this falls:

- an improved definition of innovation based on enabling better progress

- many actionable levers we can pull to more systematically and successfully innovate.

Christensen started to show us how to ” compete against luck“; the progress economy completes that journey.

Our traditional model of value – and the definitions of innovation built upon it – has been wildly successful. It powered the rise of economies, scaled global corporations, and delivered unprecedented productivity gains.

But, as financial institutions have to tell us, past performance does not guarantee future growth.

As we will see, value-in-exchange provided a coherent logic for growth in a manufacturing-dominant world. It was constructed from observations of goods-based economies, where value was embedded in outputs, exchanged at the point of sale, and realised through transactions. Today’s economies are predominantly service-based. Interaction, use, and ongoing relationships shape outcomes more than discrete exchanges.

Even without this shift, we’ll find value-in-exchange has blind spots before, after, and across the point of exchange that are increasingly impacting innovation and growth. And sitting at the root of our innovation problem is the fact that value is hard to define, agree upon, and measure. Far from being a solid basis for hunting growth, it gives us weak foundations for the future.

The question is not whether value-in-exchange worked. It did. The question is whether it remains sufficient.

To answer that, we will first examine why the exchange-based model proved so powerful. We will then confront the structural challenges it that are now more visible. Finally, we will introduce a more viable foundation for future growth – one centred not on exchanged value, but on improved well-being, operationalised through progress.

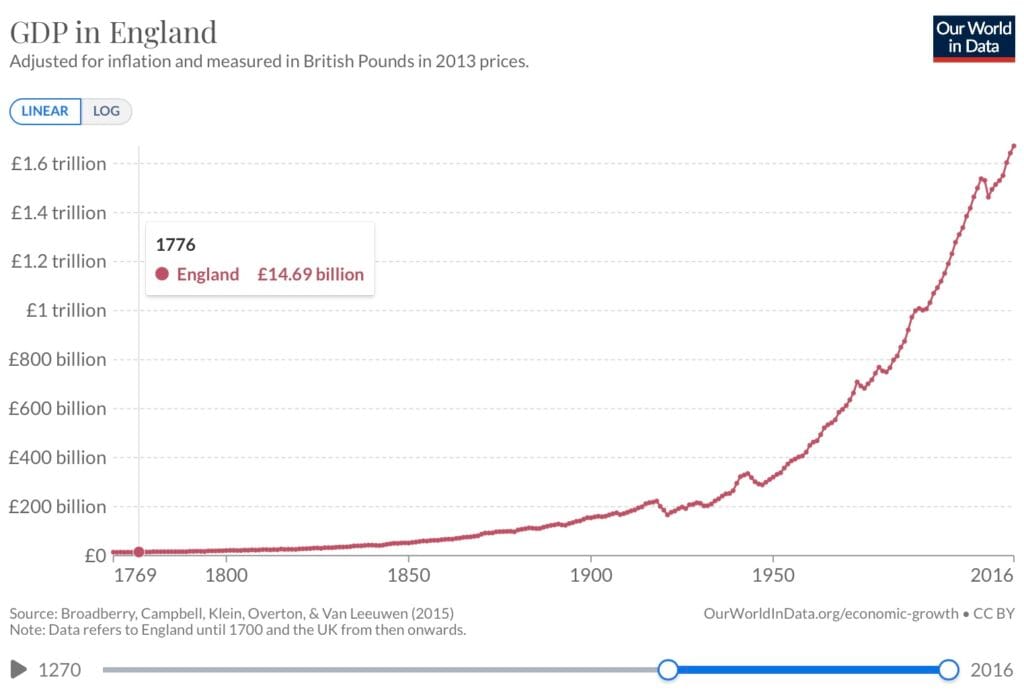

Chasing value exchange – building economies

Look at England’s GDP growth from 1776 – the year Adam Smith published The Wealth of Nations – in the graph below. From then through the early twenty-first century, expansion is explosive. Industries emerged, global trade intensified, and prosperity scaled at a pace unprecedented in human history.

I picked that starting date as it is when. Smith distinguished between value-in-use or value-in-exchange; as well as concluding that exchange was the mechanism through which nations accumulated wealth. In an era defined by the trade of goods such as tea, spices, cloth, etc, exchange translated directly into national income. Services, exemplified at the time by domestic labour, such as servants. maids, shop keepers, did not visibly increase economic wealth.

As the years progressed, manufacturing increasingly overtook agriculture as the basis of our economies. Value-in-exchange visibly became the driver of growth. It became our model of how the economy operates. McKinsey concluding in 1981 that value of a product is the greatest amount a customer would pay for it.

Manufacturing and agriculture dominated the economy and so value-in-exchange became not merely descriptive but dominant. It provided a clear causal chain: embed value in output, sell the output, accumulate capital, reinvest, scale. By 1981, McKinsey & Company could summarise the prevailing logic succinctly: a product’s value is the greatest amount a customer is willing to pay for it.

A product’s value to customers is, simply, the greatest amount of money they would pay for it.

Golub, H., and Henry, J. (1981) “Market strategy and the price-value model” via “Delivering value to customers”, McKinsey (2000)

It logically made sense then that organisations focus on increasing the value of a product in order to make the largest exchange (or largest number of exchanges). Out of this spun the academic and business functions of marketing, sales, operational effectiveness, strategy, etc, and innovation.

Under that framing, organisational behaviour followed logically. Increase perceived value to command a higher price (or more exchanges). From this foundation emerged modern marketing, sales optimisation, operational excellence, strategy disciplines — and, critically, our dominant definitions of innovation.

So , what is this value-in-exchange?

Value in exchange

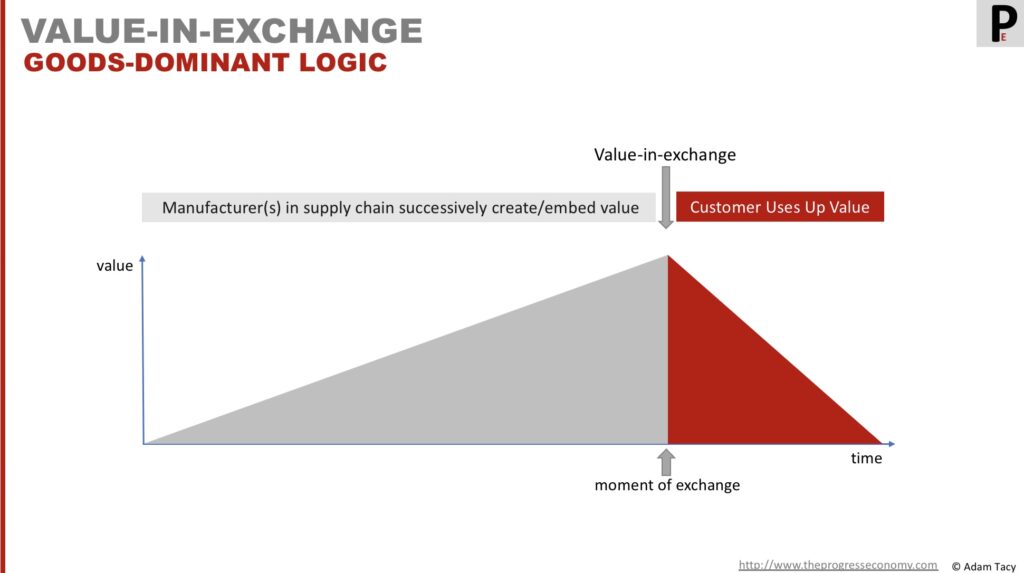

Value-in-exchange sits at the core of what Vargo & Lusch later termed goods-dominant logic. It shapes how organisations and individuals interpret markets, how they act, and how economies measure success.

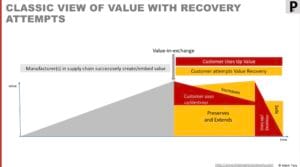

The International Organization for Standardisation defines value as something that can be created, realised, acquired, redistributed, shared, lost, or destroyed. This reflects goods-dominant logic where we see value as something that is:

- progressively added through the supply chain

- exchanged at a point of sale for something of equal value (usually cash), eventually to an end user

- used up, or destroyed, by the end owner

It’s useful to picture this graphical as below.

Value:

ISO 56000 (2025) – Innovation Management – Fundamentals and Vocabulary

- can be created, realized, acquired, redistributed, shared, lost or destroyed

- is generally determined in terms of the amount of other entities for which it can be exchanged.

This model proves extraordinarily powerful because it aligns neatly with industrial production. Outputs are tangible. Prices are observable. Growth is measurable.

As services expanded in the economy – travel, banking, education, healthcare, software, cloud computing – we did not change the logic. We extended it. Manufacturers become providers “embedding” value in their service offerings. Customers become consumers (or guests, or travellers, or…) exchanging cash for those service offerings. They then use up the services’ value.

The success of value-in-exchange as a model is not accidental. It is a logic that is institutionalised and readily observable. It therefore makes sense our definitions and actions around innovation are based upon it.

Defining innovation – adding/creating value

How do you define innovation today?

I would think you do it in terms of adding or creating value. And you wouldn’t be alone. Back in 2013, Edison, bin Ali and Torkar (2013) studied innovation in the software industry and found 41 (!) separate definitions of innovation. Where typical definition includes three aspects. Innovation:

- that has value

- is a process and an output

- that creates something new/novel (where that something could be products/ goods/ services/ processes)

Here’s ISO’s 2025 definition; it defines innovation as “a new or changed entity, realising or redistributing value“:

Innovation: new or changed entity1, realizing or redistributing value2

ISO 56000 (2025) – Innovation Management – Fundamentals and Vocabulary

1 product, service, process, model (e.g. an organizational, business, operational or value realization model), method (e.g. a marketing or management method) or a combination thereof.

2 gains from satisfying needs and expectations, in relation to the resources used; examples: revenues, savings, productivity, sustainability, satisfaction, empowerment, engagement, experience, trust.

This definition is more elegant than it might first appear. For one, it recognises that innovation can occur across a wide range of entities – products, models, methods, or any combination thereof.. – rather than our typical product view. It also defines value as a gain in satisfying needs and expectations. However the fuller definition of value later in the standard ties it back to a notion of a value exchange (see note 4 below).

value: gains from satisfying needs and expectations, in relation to the resources used

EXAMPLE: Revenues, savings, productivity, sustainability, satisfaction, empowerment, engagement, experience, trust.ISO 56000 (2025) – Innovation Management – Fundamentals and Vocabulary

- Note 1 to entry: Value is relative to, and determined by the perception of, the organization (3.2.2) and interested parties (3.2.6).

- Note 2 to entry: Value can be financial or non-financial.

- Note 3 to entry: Value can be created, realized, acquired, redistributed, shared, lost or destroyed.

- Note 4 to entry: The value of an entity is generally determined in terms of the amount of other entities for which it can be exchanged.

Yet we have an innovation problem with poor results despite effort and investments made.

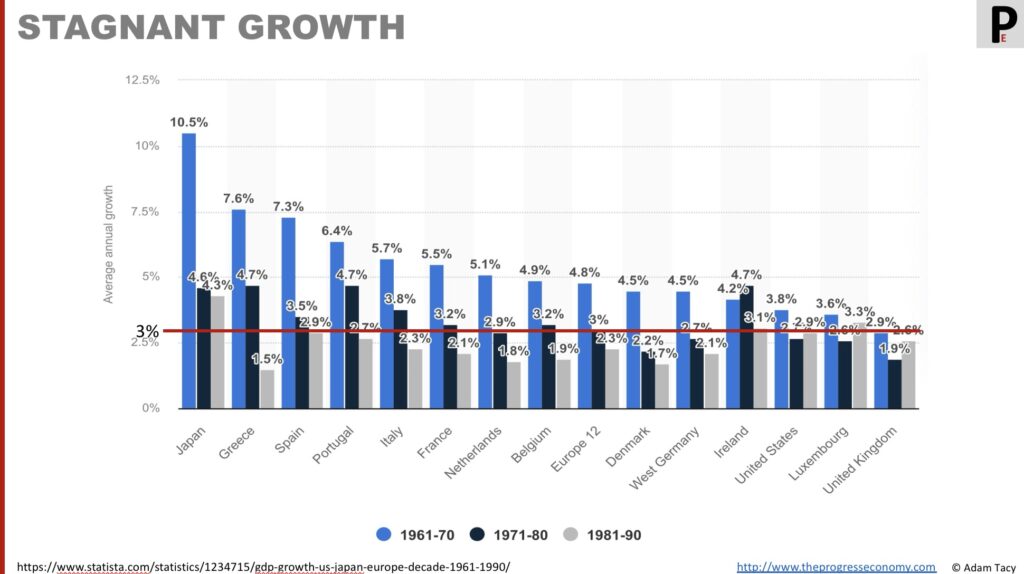

Chasing value – a growing limitation

Despite the explosive growth we saw earlier from Adam Smith’s time, if we zoom in to recent years, growth has slowed/stagnated. So much so that the International Monetary Fund warns that we may be entering a decade of structural stagnation — the “Tepid 20s” their chair called it.

The world is facing a decade of stagnation – the “Tepid 20s”.

Chair of International Monetary Fund

The growth we are expecting should be coming from innovation, something reflected by researchers recently being awarded 2025’s “Nobel prize” in economics for “research explaining innovation-driven economic growth”.

Yet executives remain frustrated by the poor returns on time, energy, and capital invested in innovation programmes that promise much but deliver little. McKinsey notes that only 6% of executives are satisfied with their innovation efforts. That means 94% are dissatisfied! And the disappointing figures continue from report after report, from research organisation after research organisation – see our innovation problem.

Only 6% of executives are happy with their innovation initiatives

McKinsey

There is a belief that innovation is inherently difficult and a quiet acceptance of poor outcomes seeps into all those innovation activities you sponsor: the hackathons, ideation competitions, brainstorming sessions, open innovation, and so on.

Too often, these efforts slide into what Steve Blank calls innovation theatre: activities that feel energising internally and look impressive in shareholder or marketing reports, but produce little in the way of tangible results. No new customers, no meaningful cost reduction, and no sustained growth.

When our innovation activities deliver few/no tangible results, we are performing innovation theater.

Steve Blank (2019) “Why Companies Do ‘Innovation Theater’ Instead of Actual Innovation”

If innovation drives growth, and growth is stalling, the question is unavoidable: what is going wrong?

It is something deeper than poor execution. The value-in-exchange model that underpins our definitions of innovation is showing strain. Four structural limitations are visible; value-in exchange:

- is built on observations from manufacturing, yet our economies are predominantly service-based

- is based on a concept – value – that is hard to define, agree upon, and measure.

- includes blind spots before, after, and across the point of exchange that are increasingly impactful

- drives the wrong type of behaviour

It is tempting to think the first two are related, that is, one is a consequence of the other. They are not. let’s take at look at each of these challenges in turn.

Challenge 1: Our logic is Based on a former economic reality

We’re navigating innovation using an incomplete map

We built our dominant logic of value, and further, innovation, on observations drawn from the manufacturing industry. That logic made sense in an era defined by industrial production, physical outputs, and efficiency at scale. When growth flowed from factories, throughput, and distribution, a goods-centred worldview provided a reliable guide.

Today, the structure of the economy looks markedly different.

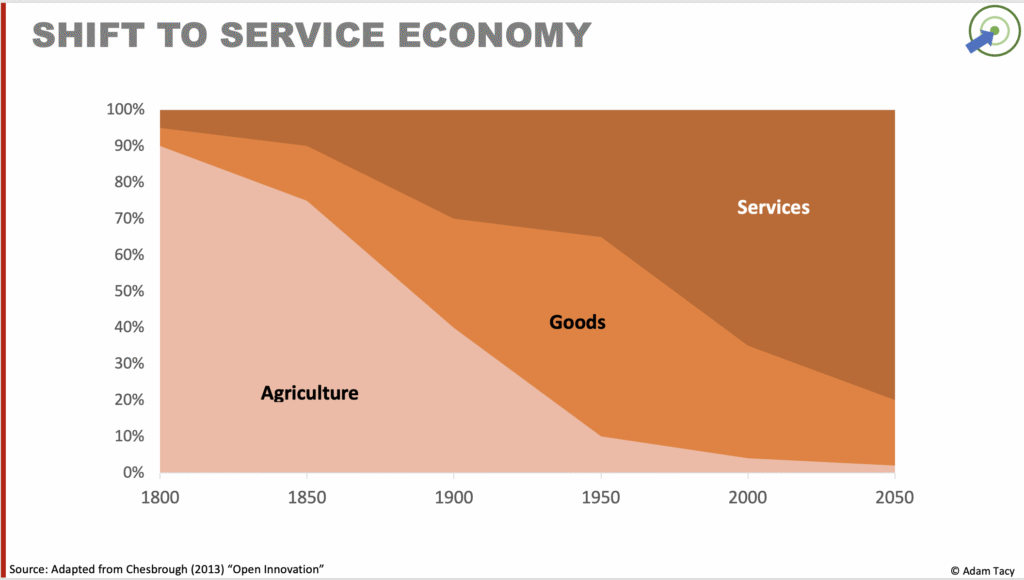

As Henry Chesbrough argues in Open Innovation, economies have undergone a profound shift. Manufacturing’s share of GDP has declined, while services have expanded rapidly.

The World Trade Organization makes the point unambiguously: services now account for roughly half of global employment and approximately two-thirds of global GDP – exceeding agriculture and industry combined. It is doing so in mature economies and in those at earlier stages of development.

The services sector today generates more jobs (50 per cent share of employment worldwide) and output (67 per cent share of global GDP) than agriculture and industry combined – and is increasingly doing so in economies at earlier stages of development

The future of trade lies in services: key trends, World Trade Organisation

If two-thirds of economic output now originates in services, the question becomes inescapable: is a goods-dominant logic the right map for navigating our modern economies?

To begin answering that, consider how goods-dominant thinking traditionally characterises services. Services are described as the so-called “five Is” (an expansion of the IHIP framework – intangibility, heterogeneity, inseparability, perishability – of Zeithmal, Parasuraman and Berr (“Problems and Strategies in Service Marketing“)) . They are:

- intangible – services cannot be physically held or inspected before purchase

- inconsistent – quality varies by instance, context, and provider

- inseparable – production and consumption often occur simultaneously

- require involvement – services typically require active customer participation

- cannot create an inventory – services cannot be stored for later use

Each characteristic defines services in contrast to goods Goods are perceived as stable, tangible, and valuable, while services are seen as variable, transient, and somehow lesser. These five Is are negative framings. Something that drives a goods and services to be considered as different and infuses a goods vs services approach to our thinking.

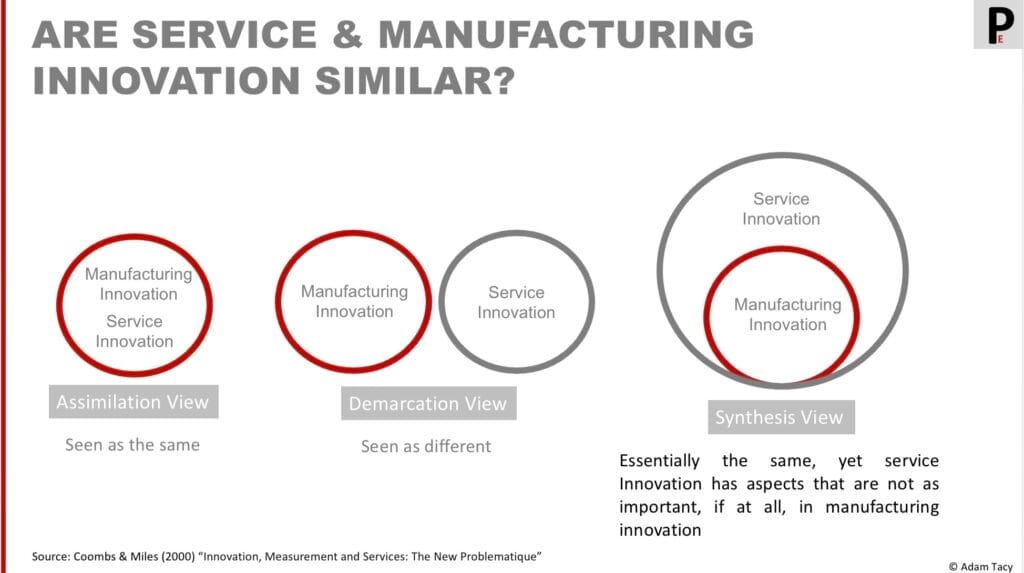

Is there, then, a distinction between innovation in goods and innovation in services?

That is something that Coombs and Miles explore in “Innovation, Measurement and Services: The New Problematique“. They outline three prevailing views: assimilation, demarcation, and synthesis. Witel et al’s (2016) “Defining service innovation: A review and synthesis” provides a deep literature review of those three categories.

Under an assimilation view, innovation in services and manufacturing are seen as essentially the same. Whereas under a demarcation view, they are viewed as fundamentally different.

Since growth and innovation were strong in goods-dominant economy and visibly struggle in today’s predominantly service-based economies, the assimilation view would appear to be insufficient. Yet we did have growth and innovation in services even when having a goods-dominant logic perspective. Therefore it’s hard to argue for the demarcation view. Indeed, Vargo and Lusch promote the view in their service-dominant logic – an alternative to goods-dominant logic we will lean heavily on in our solution – that goods are distribution mechanisms for service. That perspective collapses the hard boundary between products and services meaning the demarcation view also falls short.

That leaves us with the synthesis view. Where innovation in goods and in services are understood as sharing a common foundation, while service innovation introduces dimensions that are less central – or absent – in manufacturing contexts.

The conclusion follows directly. An innovation model derived from goods-dominant logic no longer provides a complete guide to a service-dominant reality. The tools that propelled previous waves of growth remain valuable — but they are insufficient. To sustain progress, we must upgrade our map.

Challenge 2: Value is difficult to define, agree upon, and measure

Value is hard to define, agree upon, and measure; activities based on a confused definition lead to poor performance

Distinct from whether we have the complete map, we have a challenge in defining what we mean by value. At first glance, the concept feels obvious. The moment we probe beneath the surface, it becomes elusive. As Christian Grönroos observes, “value is a concept that is difficult to define”. We invoke the term constantly – in strategy decks, board discussions, innovation briefs – yet seldom pause to establish a shared definition.

The struggle is not new. In 1776, Adam Smith distinguished between value in exchange – purchasing power – and value in use – the utility derived from an object. More than a century later, Karl Marx noted that earlier English writers draw a distinction, using “worth” to describe use value and reserving “value” for exchange value.

More recently, Karababa and Kjeldgaard catalogued a proliferation of competing value constructs – use value, exchange value, aesthetic value, identity value, instrumental value, economic value, social value, shareholder value, symbolic value, functional value, utilitarian value, hedonic value, perceived value, community values, emotional value, expected value, brand value – noting that these concepts are frequently deployed without an explicit conceptual foundation.

…use value, exchange value, aesthetic value, identity value, instrumental value, economic value, social values, shareholder value, symbolic value, functional value, utilitarian value, hedonic value, perceived value, community values, emotional value, expected value, and brand value…

Karababe, E. and Kjeldgaard, D. (2013) “Value in Marketing: Toward Sociocultural Perspectives”

…are examples of different notions of value, which are frequently used without having an explicit conceptual understanding in marketing and consumer research.

It is little surprise, then, that Anderson and Narus found that remarkably few suppliers in business markets could answer basic questions such as: How do you define value? Can you measure it?

remarkably few suppliers in business markets are able to answer…questions like…How do you define value? Can you measure it?

Anderson and Narus (1998) ”Business Marketing: Understand what customers value”

Inside organisations, the consequences are tangible. Teams are instructed to “create value” without a consistent reference point. Products are enhanced, features are added, portfolios expand – yet offerings fail to resonate with value customers actually seek.

Take Levitt’s observation about marketing myopia. People don’t generally value the drill, they value the hole it produces. Decades later Christensen observed that most marketing leaders agree with Levitt’s observation, yet few act on it. Ww find drill manufacturers value the drill and innovation focuses only on features to add to a drilling order to make an new exchange.

People don’t want to buy a quarter-inch drill. They want a quarter-inch hole

Levitt (1960), Marketing Myopia

Measurement compounds the problem. In practice, measurement of value frequently collapses into price. As McKinsey summarised, value is the greatest amount a customer is willing to pay. What begins as a multidimensional construct narrows to a monetised transaction.

A product’s value to customers is, simply, the greatest amount of money they would pay for it.

Golub, H., and Henry, J. (1981) “Market strategy and the price-value model” via “Delivering value to customers”, McKinsey (2000)

Step back and the implication becomes clear. We define innovation as the creation or realisation of value. Yet neither organisations nor customers share a stable, aligned definition of value, and measurement often defaults to price. Under those conditions, inconsistent innovation performance is not surprising; it is structurally embedded.

The question is not whether value matters. It unquestionably does. The question is whether our current conception of value provides a sufficiently robust foundation for the growth we now seek.

Challenge 3: There are blind spots

value-in-exchange has numerous blindspots, before, after and across the point of exchange

Value-in-exchange contains structural blind spots – before, after, and across the point of exchange.

For much of the past, these were manageable, perhaps not noticeable or even advantageous. Today, as traditional growth avenues narrow, they are becoming increasingly consequential.

- Prioritising consistency over customisation – missing value before exchange

- Chasing the next transaction – missing post-exchange value

- Valuing new exchanges over circular thinking – missing value across the exchange

- Elevating goods over services – narrowing the solution space

- Falling into marketing myopia –

- Favouring simple exchange over more innovative business models

- Assuming providers define value

At its core, the exchange logic optimises the transaction. It focuses managerial attention on producing something efficiently, transferring it at scale, and securing the next sale. What falls outside that transaction frame often escapes strategic consideration.

Consistency over customisation – missing value before exchange

A goods-dominant logic rewards standardisation. Consistent products reduce unit costs, enable inventory, and separate production from use. They scale cleanly. Automotive manufacturers, for example, constrain personalisation to a limited palette of paint colours and option packages in order to preserve manufacturing efficiency.

Yet this consistency comes at a cost. It restricts the opportunity to generate value before exchange by tailoring the offering to the specific circumstances of the customer. Customisation demands involvement, flexibility, and often co-creation. Exchange logic discourages all three.

As a result, organisations capture efficiency while leaving differentiated value unrealised.

Chasing the next exchange – Missing value after the exchange

Once the exchange occurs, an organisation’s attention has already shifted to the next sale. Post-purchase life receives far less strategic focus. But significant value exists beyond the moment of transaction. In their work on value propositions, Osterwalder and Pigneur note that value consumption, renewal, and transfer are routinely overlooked (Modelling value propositions in eBusiness).

Consider the automotive example again. The manufacturer captures the exchange when the vehicle is sold and then has little interest. The moment the customer drives away, the car’s resale value declines. Over time, use consumes what remains.

Yet servicing, repair, refurbishment, modification, resale, and lifecycle extension all recover declined value. These activities matter deeply to customers. But frequently not to the manufacturer.

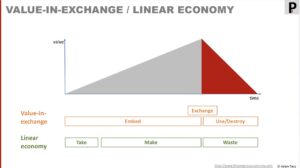

Favouring more exchanges over circular – Missing value across the exchange

Exchange logic often rewards consumption velocity because it drives repeat transactions at higher frequency. The faster the value is is used up, the sooner another exchange occurs.

Gillette’s “razor and blade” model, often celebrated in business schools as a masterstroke of recurring revenue, is an example. The firm sells the razor handle at low cost, then captures margin through a continuous stream of blade replacements.

The same dynamic can be found in fast fashion, where value is extracted through high volume and low price, with little consideration of the environmental or social aspects.

Financially elegant, but these exemplify how value-in-exchange’s “embed-exchange-destroy” aligns with the non-circular economy’s “take-make-waste”.

The Ellen MacArthur Foundation has identified transitioning to a circular economy requires us to revisit the very notion of value creation.

One of the biggest challenges… to transition from linear to circular is that it requires… revisiting the very notion of value creation.

Ellen MacArthur Foundation (2023), From ambition to action: an adaptive strategy for circular design

As long as value is measured primarily at the point of exchange, why put effort in before the exchange to allow value (durability, reuse, regeneration, and systemic impact) to be realised.

Goods over services – Distorting the solution space

Exchange logic privileges goods because they align neatly with its assumptions. Goods can be manufactured independently of use, inventoried, priced, and transferred. They appear to “embed” value, which customers later consume.

Even when firms offer services, they often attempt to standardise them so they resemble goods — predefined packages, fixed scopes, rigid pricing. The goods-versus-services dichotomy persists, implicitly positioning services as less attractive.

Yet much of today’s economy is intangible. Digital music, streaming video, cloud software, and eBooks require no inventory. Physical products increasingly rely on just-in-time production and integrated service ecosystems. Additive manufacturing and on-demand production further weaken the logic of embedded value.

A classic example is the music industry’s slow shift from selling physical products to embracing streaming. Clinging to goods lost the market for music to the now streaming giants.

The goods-centric bias narrows the solution space at precisely the moment when flexibility and integration are strategic advantages.

Marketing myopia – Limiting the solution space

People don’t want to buy a quarter-inch drill. They want a quarter-inch hole

Levitt (1960), Marketing Myopia

Value-in-exchange thinking reinforces a deeper risk identified by Theodore Levitt in his analysis of Marketing Myopia. Customers do not seek products; they seek outcomes. Yet organisations frequently define their business in terms of the goods they produce rather than what customers are attempting to achieve.

Simple exchange over business model innovation

Exchange logic favours clear, bilateral, one-off transactions that covers the perceived value a manufacturer sees in a product. Business models that fragment, distribute, or reconfigure exchanges – such as subscription, subsidised or platform as a service – can feel misaligned with that.

Manufacturer as judge of value

Finally, exchange logic implicitly positions the producer as the primary arbiter of value; which they set as price. Customer purchase/use is treated as validation of that price, and therefore value.

The rollout of self-service checkouts in supermarkets illustrates the tension when manufacturers/producers believe they set value. Retailers prioritised cost efficiency and operational throughput, presuming that speed and convenience would be valued by customers.

The subsequent backlash – increased theft, intrusive anti-theft measures, customer dissatisfaction, and partial reversals – is not a story of failed change management. It revealed a misalignment between producer-defined and customer-experienced (and wanted) value.

That’s a dangerous misstep, especially as we saw earlier that we struggle to define and agree what value is.

Even highlighting that value is contextual – the self-service checkout is valuable to some customers in some contexts and not others – and that resistance to innovation plays a part – we’re not just guiding/waiting for innovation to progress through an adoption curve.

Challenge 4: Drives limiting behaviour

When value is defined as something embedded in outputs and realised at exchange, organisations risk optimising what they produce and how efficiently they transact – not what ultimately changes for the customer.

That distinction seems subtle. In practice, it shapes the entire enterprise.

If value crystallises at the moment of exchange, then the exchange becomes the focal point of strategy. Performance systems prioritise revenue, margin, market share, and transaction growth. Innovation concentrates on features, packaging, pricing, and channel optimisation. Success is measured by what leaves the organisation, not by what improves in the customer’s world.

Over time, this logic hardens into structure. Capital flows toward initiatives that protect or increase exchange value. Metrics reinforce short-term monetisation. Post-sale experience is managed defensively – to reduce complaints, limit churn, or enable cross-sell – rather than offensively, as the primary arena where customer outcomes are realised.

The organisation becomes highly skilled at refining the transaction.

But markets evolve. Customer expectations expand. And competitors emerge who are not anchored to the same logic.

Consider the contrast between a start-up and an established incumbent.

A start-up begins with a customer problem. It survives only if it helps someone make meaningful progress. Its operating model is fluid. It iterates rapidly, interacts continuously with early users, adapts its offer, and reshapes its proposition in response to real-world feedback. It is less concerned with defending margins and more concerned with proving relevance. The exchange is necessary, but it is not the endgame; it is validation that progress has been enabled.

An established company operates under different pressures. It carries fixed costs, investor expectations, brand commitments, and margin targets. Existing revenue streams must be protected. It manages portfolios, channels, and cost structures optimised around scale. Under a value-in-exchange logic, innovation becomes a matter of extending product lines, defending price points, and increasing basket size. Customer interaction narrows to what can be standardised and monetised. Flexibility gives way to efficiency.

Neither model is inherently flawed. But they are governed by different economic instincts.

The start-up asks: “Did we help the customer move forward?”

The incumbent asks: “Did we protect and grow the exchange?”

When the dominant logic centres on exchange value, established firms systematically underinvest in the messy, contextual, and longitudinal work of helping customers realise progress. They focus on what can be produced and priced, not on what must be enabled and supported.

This is not a failure of leadership or intent. It is a predictable outcome of the system’s design.

However, the consequences are strategic. As markets shift toward service, experience, and ecosystem-based competition, firms optimised for transactions find themselves competing against organisations optimised for outcomes. The former refine efficiency; the latter expand relevance.

Over time, this creates a widening gap. Acquisition costs rise as differentiation erodes. Feature proliferation replaces meaningful advancement. Retention weakens because customers achieve only partial progress and continue searching for better solutions.

If we define value at the moment of exchange, we will continue to optimise transactions while under-optimising transformation.

The innovation problem is structural: for future growth we have the wrong endgame (adding value), the wrong mental model (value-in-exchange), and the wrong success lens (supplier-centric rather than Seeker-centric).

We are navigating the world of innovation using an incomplete map to a destination we struggle to agree on.

Let’s fix that

major rewriting below here

Improving well-being – the necessary shift

Our first step towards retiring growth and fixing innovation is to tackle the issue of value, and its exchange.

Grönroos wrote that value emerges as products do something for the user, it is not exchanged..

…value really emerges for customers when goods and services do something for them.

Grönroos (2004) “Adopting a service logic for marketing”

Think of Levitt’s marketing myopia again. Customers are not interested in the 1/4 inch drill. It has no value whilst sitting on the workbench; only potential. When they use the drill to make the whole, then whatever we call value just now emerges. Once the hole is made, the drill goes back to having only potential.

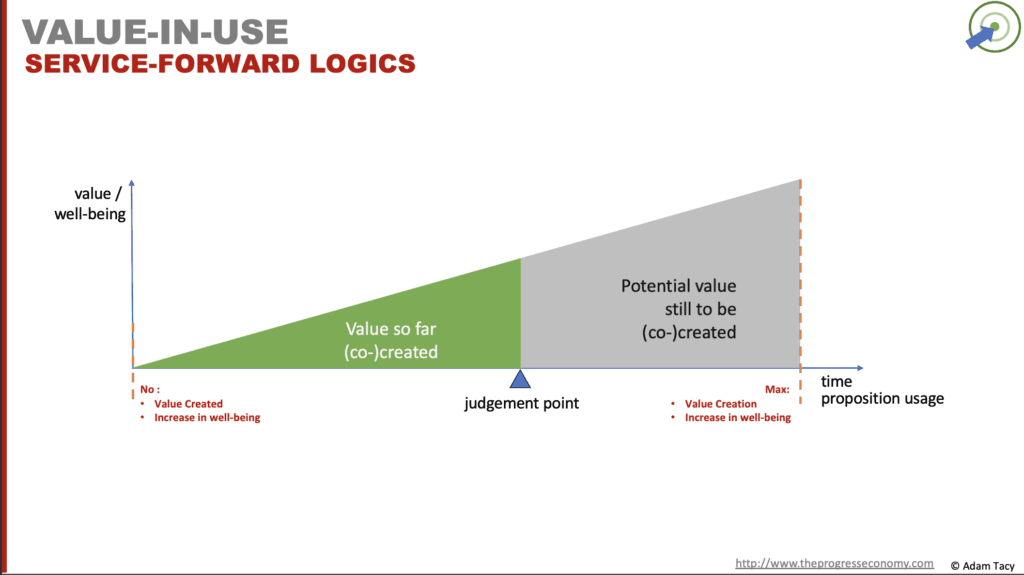

Value-in-use as this model is named aims to shift the focus of how value is seen away from value-in-exchange’s embed-exchange-destroy. Value is no longer an output it is an outcome and importantly, the time logic of how value is created is altered.

the time logic of marketing exchange becomes open-ended, from pre-sale service interaction to post-sale value-in-use, with the prospect of continuing further, as relationships evolve

Ballantyne and Varey (2006) “Creating Value-in-use Through Marketing Interaction: The Exchange Logic of Relating, Communicating and Knowing”, Marketing Theory Vol. 6, No. 3(3)

Without an obsessive focus on a point of exchange, we’re freed to see that value emerges before, after, and across the now non-existent exchange point. It emerges progressively. Only our own decisions alter the timelines within which we see possibilities for adding value.

Another implication, that becomes more obvious when thinking in terms of use rather than exchange is a broadening of the solution space. If we’re a hammer manufacturer focussed on exchange we’re biased to improve the drill. If we see ourselves as a creator of holes, then manufacturing drill is one option. Providing a handyman service is another. Or perhaps there are other tools that are better. Maybe we produce small segments of plasterboard with pre-made holes. You simply remove the section of plasterboard where you want the hole and replace with our plasterboard segment. Marketing myopia and the growth-damaging goods vs services discussion can melt away. In fact a new interpretation of the old services limitations step forwards as described by Vargo & Lusch

Vargo and Lusch (2004) “The Four Service Marketing Myths”; Journal of Service Research 6(4):324

- intangibility => unless tangibility has a marketing advantage, it should be reduced or eliminated if possible

- inconsistency => the normative marketing goal should be customization, rather than standardization

- inseparability / involvement => the normative marketing goal should be to maximize consumer involvement in value creation

- inventory => the normative goal of the enterprise should be to reduce inventory and maximize service flow

Now we can define service (singular) as distinct from services (plural) which invokes a difference to goods. Service (plural) is the application of capabilities to benefit another. Goods become are distribution mechanism of service – they freeze the application of capabilities allowing them time to be transported in time/space and unfrozen in acts of resource integration.

This is easy to visualise with the example of music. You could go to watch your favourite band play live. That’s a service – where the band members apply their musical instrument playing capabilities for your benefit. Their performance could also be recorded onto a CD, or vinyl – which are goods. Those goods are then distributed through shops to you and me. When you play the CD on your CD player, the performance is unfrozen and you benefit from the musicians capabilities. We no longer have a goods vs services debate.

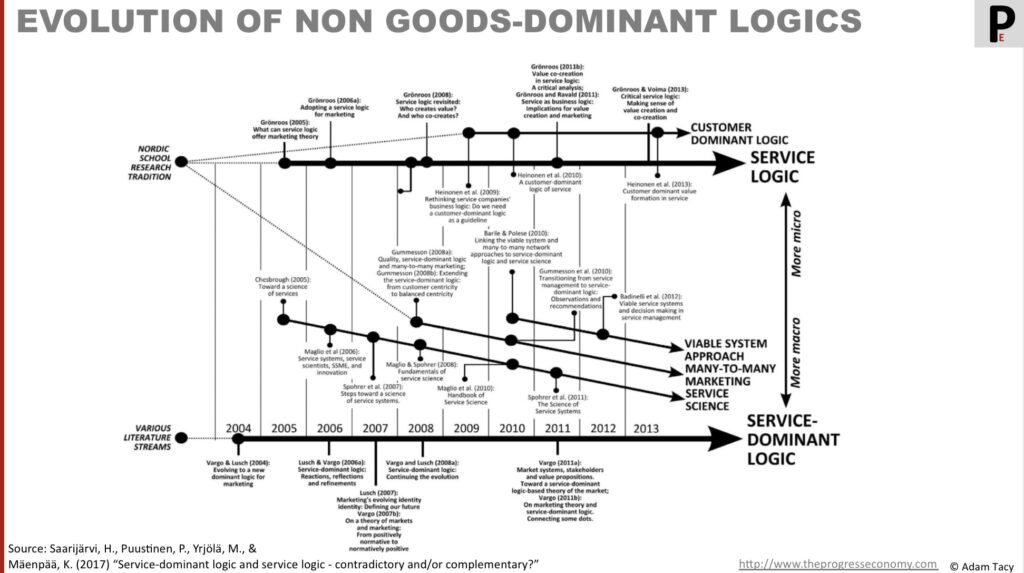

Academically we are now in the realm of service-forward logics – where we see service(s) as the dominant activity and determine what goods mean in relation to them. This is the opposite of goods-dominant logic.

These logics – in particular Grönroos’ service logic and Vargo and Lusch’s service-dominant logic. – provide a more complete map of economic actions in a service-dominant world.

Our next move forwards is to break the behaviours that value-in-exchange encourages. And those are driven by the use of the word value and the concept of exchange. The concept we’ve already changed into value-in-use.

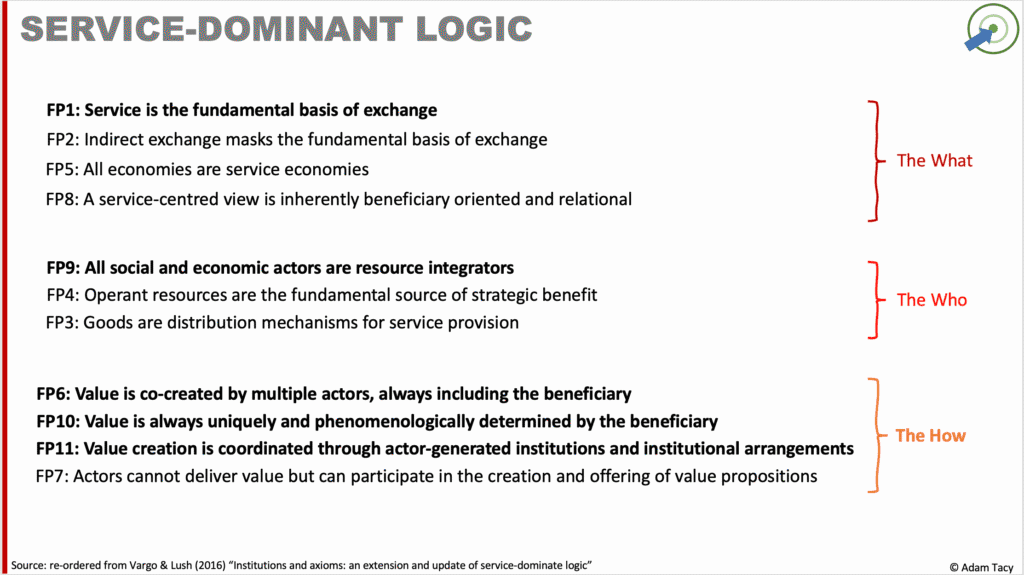

Let’s go back to Grönroos’ insight that value emerges as a product is used to do something. Value here is still the same hard to define, agree upon, and measure concept as before; that also risks enticing us back into exchange world habits. After several iterations of evolving service-dominant logic, Vargo & Lusch arrived at value equates to improved well-being.

Value creation is ultimately about improving the well-being of actors.

Vargo, S. & Lusch, R. (2016) Institutions and Axioms: An Extension and Update of Service-Dominant Logic.

We could call the model improved-well-being-in-use. A bit of a mouthful, but we have no conceptual tie back to something that can be exchanged. Well-being doesn’t make sense to exchange,

SDL stresses that well-being is phenomenologically determined. This means:

- Only the actor experiencing the outcome can determine whether their well-being improved.

- It is context dependent.

- It cannot be fully defined by the producer or supplier.

This is captured in one of SDL’s foundational premises:

Value is uniquely and phenomenologically determined by the beneficiary.

So well-being is not universal or fixed—it depends on the actor’s goals, circumstances, and comparisons.

Service-dominant logic correctly identifies well-being as the ultimate outcome of value creation. Yet “well-being” risk being just a replacement for “value” in being difficult to operationalise in managerial practice. The Progress Economy addresses this gap by reframing well-being as progress—observable movement toward more desired states.

Operationalising Well-being – making progress

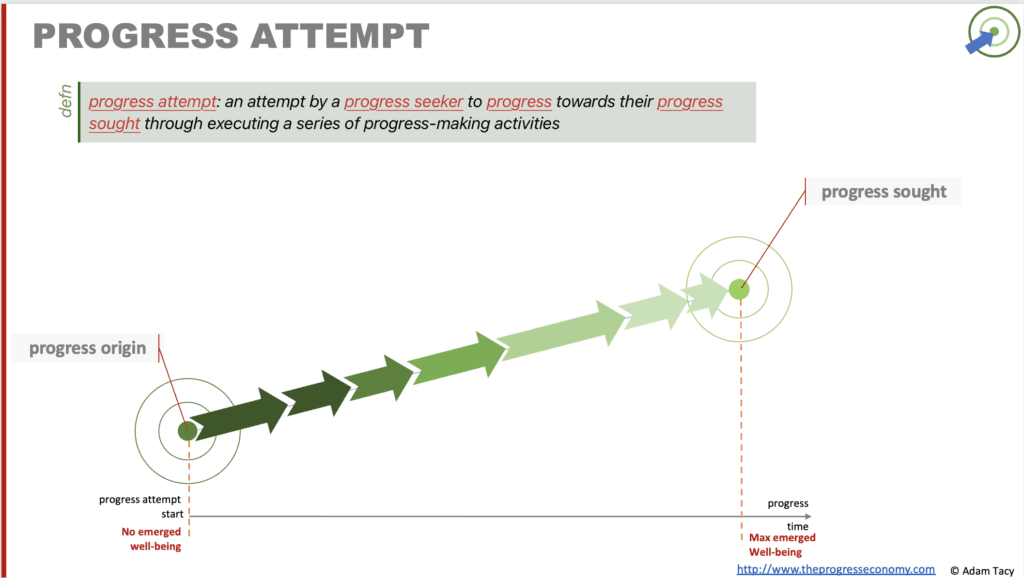

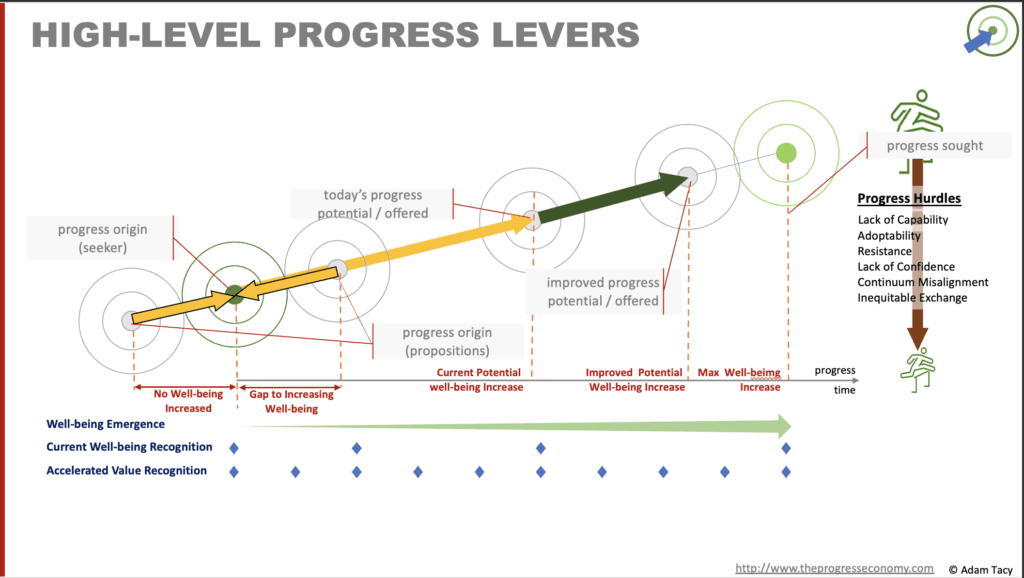

The second shift is identifying that “in-use” relates to making progress over time to a more desirable state. Progress is the action that improves well-being; and well-being is a set of progress comparisons. When your progress reached, for example, matches your progress sought then you have maximised the improvement in your well-being.

- B2B: Cloud infrastructure providers did not simply offer cheaper servers – they enabled businesses to scale without owning data centers (aligning to progress sought), shifting capital expenditure to operating expenditure and reducing operational risk (lowering progress hurdles).

- Public sector: Digital identity programs don’t just improve “efficiency” – they help citizens progress through life events such as opening a bank account, accessing healthcare (aligning to progress sought) with less administrative friction (aligning to progress origin and reducing progress hurdles; though digital ids can increase the resistance progress hurdle if not managed).

- B2C: Streaming platforms did not just add “value” over DVDs – they removed friction from the progress of accessing and enjoying entertainment (aligned with progress sought)

These shifts allow us to build a useful model of the economy.

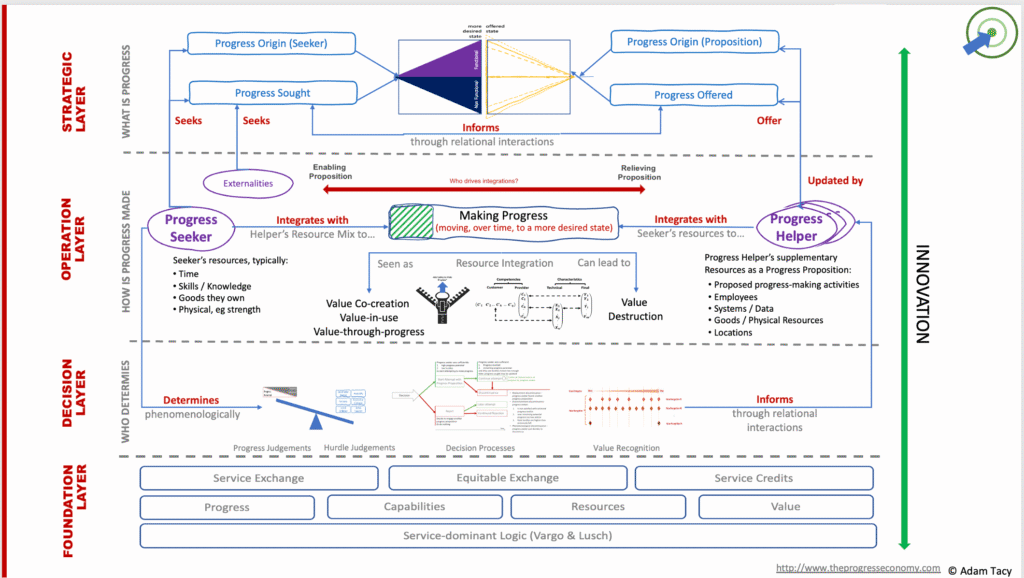

Progress – an operating model for the economy

Taking a progress view of the world reveals an operating model that both builds on value-in-use’s minimisation of value-in-exchange challenges and gives us clear, definable, view of “value creation” (making progress) and how “value” (progress comparisons) can be measured.

The progress economy works this way:

- all actors are seeking to make progress with all aspects of their life

- progress is made by one or more actors applying capabilities through resource integration

- comparing progress leads to judgements of well-being – potential increase, emerged increase, realised increase etc.

- progress is hindered by lacking necessary capabilities (the foundation progress hurdle)

- there is an uneven distribution of capabilities across actors (creating a market for exchanging, often indirectly)

- some actors offer their capabilities to others (as progress propositions)

- progress propositions lift five additional progress hurdles (adoptability, resistance, misalignment on continuum, lack of confidence, and inequitable exchange)

These four innovation outcomes are high level progress levers – aspects where we can best focus our creativity to identify progress improving activities.

The operating model, and context hierarchy, help us discover numerous lower level progress levers that support those four outcomes. These dramatically increase the odds that innovation efforts convert into successful outcomes.

We are no longer “competing against luck“.

The outcome: Improving innovation

Innovation is reframed from “how do we add value?” to “how do we improve well-being?” which itself is “how do we make (or help others make) better progress?”.

Now we leverage the operating model of progress to discover four innovation outcomes:

- making better progress

- making progress better

- reducing one or more of the progress hurdles

- accelerating possibility for well-being recognition.

Innovation becomes the disciplined discovery and execution of new ways for Progress Seekers to make better progress, with lower progress hurdles, and quicker value recognition. More formally:

innovation: creating and executing new – to the individual, organisation, market, industry, world – progress propositions that offers some combination of:

- improving progress towards progress sought

- making today’s progress better

- reducing one or more of the six progress hurdles

- accelerating possibility of well-being recognition frequency

whilst maintaining, or improving, the survivability of the innovator and/or ecosystem

The outcome: Realising sales and innovation are two sides of the same coin

The last, perhaps surprising, implication of our progress-forward thinking is the distinction between sales and innovation dissolves. Look at the four outcomes in our definition – making better progress, making progress better, lowering hurdles, and accelerating well-being recognition. Are they not the same outcomes you expect a successful sales approach to offer customers?

Innovation operates more “off-line” to design new ways of helping, whereas sales operates “in-line” to match those ways to real Seekers in real contexts.

In fact, sales interactions often generate local innovations and market intelligence that, when captured, can directly strengthen innovation upstream.

Sales and innovation are two sides of the same coin.

Let’s progress together through discussion…